Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

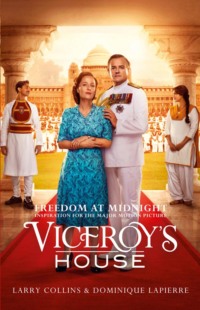

Kitabı oku: «Freedom at Midnight: Inspiration for the major motion picture Viceroy’s House», sayfa 3

A harsh schooling awaited the empire’s young servants at the end of their first passage to India. They were sent to remote posts, covered by primitive roads and jungle tracks, inhabited, if at all, by only a few Europeans. By the time they were twenty-four or twenty-five, they often found themselves with sole responsibility for handing down justice to and administering the lives of a million or more human beings, in areas sometimes larger than Scotland.

His apprenticeship in those remote districts eventually qualified a young officer to take his privileged place in one of those green and pleasant islands from which the aristocracy of the Raj ran India, ‘cantonments’, golden ghettos of British rule appended like foreign bodies to India’s major cities.

Inevitably, each enclave included its green expanse of garden, its slaughterhouse, its bank, its shops and a squat stone church, a proud little replica of those in Dorset or Surrey. Its heart was always the same: an institution that seemed to grow up wherever more than two Englishmen gathered, a club. There, in the cool of the afternoon, the British of the cantonment could gather to play tennis on their well-kept grass courts, or slip into white flannels for a cricket match. At the sacred hour of sundown, they sat out on their cool lawns or on their rambling verandas while white-robed servants glided past with their ‘sundowners’, the first whisky of the evening.

The parties and receptions in imperial India’s principal cities – Bombay, Calcutta, Lahore, Delhi, Simla – were lavish affairs. ‘Everyone with any standing had a ballroom and a drawing-room at least eighty feet long,’ wrote one grande dame who lived in Victorian India. ‘In those days, there were none of those horrible buffets where people go to a table with a plate and stand around eating with whomsoever they choose. The average private dinner was for thirty-five or forty with a servant for each guest. Shopkeepers and commercial people were never invited nor, of course, did one ever see an Indian socially, anywhere.

‘Nothing was as important as precedence and the deadly sin was to ignore it. Ah, the sudden arctic air that could sweep over a dinner party if the wife of an ICS joint secretary should find herself seated below an army officer of rank inferior to that of her husband.’

Much of the tone of Victorian India was set by the ‘memsahibs’, the British wives. To a large extent, the social separation of the English and the Indians was their doing. Their purpose, perhaps, was to shield their men from the exotic temptations of their Indian sisters, a temptation to which the first generations of Englishmen in India had succumbed with zest, leaving behind a new Anglo-Indian society suspended between two worlds.

The great pastime of the British in India was sport. A love of cricket, tennis, squash and hockey would be, with the English language, the most enduring heritage they would leave behind. Golf was introduced in Calcutta in 1829, 30 years before it reached New York, and the world’s highest course laid out in the Himalayas at 11,000 feet. No golf bag was considered more chic on those courses than one made of an elephant’s penis – provided, of course, its owner had shot the beast himself.

The British played in India but they died there, too, in very great numbers, often young. Every cantonment church had its adjacent graveyard to which the little community might carry its regular flow of dead, victims of India’s cruel climate, her peculiar hazards, her epidemics of malaria, cholera, jungle fever. No more poignant account of the British in India was ever written than that inscribed upon the tombstones of those cemeteries.

Even in death India was faithful to its legends. Lt St John Shawe, of the Royal Horse Artillery, ‘died of wounds received from a panther on 12 May 1866, at Chindwara’. Maj. Archibald Hibbert, died 15 June 1902, near Raipur after ‘being gored by a bison’, and Harris McQuaid was ‘trampled by an elephant’ at Saugh, 6 June 1902. Thomas Henry Butler, an Accountant in the Public Works Department, Jubbulpore, had the misfortune in 1897 to be ‘eaten by a tiger in Tilman Forest’.

Indian service had its bizarre hazards. Sister Mary of the Church of England Foreign Missionary Services died at the age of 33, ‘Killed while teaching at the Mission School Sinka when a beam eaten through by white ants fell on her head’. Major General Henry Marion Durand of the Royal Engineers, met his death on New Year’s Day 1871 ‘in consequence of injuries received from a fall from a Howdah while passing his elephant through Durand Gate, Tonk’. Despite his engineering background, the general had failed that morning to reach a just appreciation of the difference in height between the archway and his elephant. There proved to be room under it for the elephant, but none for him.

No sight those graveyards offered was sadder, nor more poignantly revealing of the human price the British paid for their Indian adventure, than their rows upon rows of undersized graves. They crowded every cemetery in India in appalling numbers. They were the graves of children, children and infants killed in a climate for which they had not been bred, by diseases they would never have known in their native England.

Sometimes a lone tomb, sometimes three or four in a row, those of an entire family wiped out by cholera or jungle fever, the epitaphs upon those graves were a parents’ heartbreak frozen in stone: ‘In memory of poor little Willy, the beloved and only child of Bomber William Talbot and Margaret Adelaide Talbot, the Royal Horse Brigade, Born Delhi 14 December 1862. Died Delhi 17 July 1863.’

In Asigarh, two stones side by side offer for eternity the measure of what England’s glorious imperial adventure meant to many an ordinary Englishman. ‘19 April 1845. Alexander, 7-month-old son of Conductor Johnson and Martha Scott. Died of cholera,’ reads the first. The second, beside it, reads: ‘30 April 1845, William John, 4-year-old son of Conductor Johnson and Martha Scott. Died of cholera.’ Under them, on a larger stone, their grieving parents chiselled a last farewell:

One blessing, one sire, one womb

Their being gave.

They had one mortal sickness

And share one grave

Far from an England they never knew.

Obscure clerks or dashing blades, those generations of Britons policed and administered India as no one before them had.

Their rule was paternalistic, that of the old public schoolmaster disciplining an unruly band of boys, forcing on them the education he was sure was good for them. With an occasional exception they were able and incorruptible, determined to administer India in its own best interests – but it was always they who decided what those interests were, not the Indians they governed.

Their great weakness was the distance from which they exercised their authority, the terrible smugness setting them apart from those they ruled. Never was that attitude of racial superiority summed up more succinctly than by a former officer of the Indian Civil Service in a parliamentary debate at the turn of the century. There was, he said, ‘a cherished conviction shared by every Englishman in India, from the highest to the lowest, by the planter’s assistant in his lonely bungalow and by the editor in the full light of his presidency town, from the Chief Commissioner in charge of an important province to the Viceroy upon his throne – the conviction in every man that he belongs to a race which God has destined to govern and subdue’.

The massacre of 680,000 members of that race in the trenches of World War I wrote an end to the legend of a certain India. A whole generation of young men who might have patrolled the Frontier, administered the lonely districts or galloped their polo ponies down the long maidans was left behind in Flanders fields. From 1918 recruiting for the Indian Civil Service became increasingly difficult. Increasingly, Indians were accepted into the ranks both of the civil service and the officer corps.

On New Year’s Day 1947, barely a thousand British members of the Indian Civil Service remained in India, still somehow holding 400 million people in their administrative grasp. They were the last standard bearers of an elite that had outlived its time, condemned at last by a secret conversation in London and the inexorable currents of history.

* Although Mountbatten didn’t know it, the idea of sending him to India had been suggested to Attlee by the man at the Prime Minister’s side, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Stafford Cripps. It had come up at a secret conversation in London in December, between Cripps and Krishna Menon, an outspoken Indian left-winger and intimate of the Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru. Menon had suggested to Cripps and Nehru that Congress saw little hope of progress in India so long as Wavell was Viceroy. In response to a query from the British leader, he had advanced the name of a man Nehru held in the highest regard, Louis Mountbatten. Aware that Mountbatten’s usefulness would be destroyed if India’s Moslem leaders learned of the genesis of his appointment the two men had agreed to reveal the details of their talk to no one. Menon revealed the details of his conversation with Cripps in a series of conversations with one of the authors in New Delhi in February 1973, a year before his death.

* Wavell too had recommended a time limit to Attlee during a London visit in December 1946.

TWO

‘Walk Alone, Walk Alone’

Srirampur, Noakhali, New Year’s Day, 1947

Six thousand miles from Downing Street, in a village of the Gangetic Delta above the Bay of Bengal, an elderly man stretched out on the dirt floor of a peasant’s hut. It was exactly twelve noon. As he did every day at that hour, he reached up for the dripping wet cotton sack that an assistant offered him. Dark splotches of the mud packed inside it oozed through the bag’s porous folds. The man carefully patted the sack on to his abdomen. Then he took a second, smaller bag and stuck it on his bald head.

He seemed, lying there on the floor, a fragile little creature. The appearance was deceptive. That wizened 77-year-old man beaming out from under his mudpack had done more to topple the British Empire than any man alive. It was because of him that a British Prime Minister had finally been obliged to send Queen Victoria’s great-grandson to New Delhi to find a way to give India her freedom.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an unlikely revolutionary, the gentle prophet of the world’s most extraordinary liberation movement. Beside him, carefully polished, were the dentures he wore only when eating and the steel-rimmed glasses through which he usually peered out at the world. He was a tiny man, barely five feet tall, weighing 114 pounds; all arms and legs like an adolescent whose trunk has yet to rival the growth of his limbs. Nature had meant Gandhi’s face to be ugly. His ears flared out from his oversized head like the handles of a sugar bowl. His nose buttressed by squat, flaring nostrils thrust its heavy beak over a sparse white moustache. Without his dentures, his full lips collapsed over his toothless gums. Yet Gandhi’s face radiated a peculiar beauty because it was constantly animated, reflecting with the quickly shifting patterns of a magic lantern his changing moods and his impish humour.

To a century fraught with violence, Gandhi had offered an alternative, his doctrine of ahimsa – non-violence. He had used it to mobilize the masses of India to drive England from the sub-continent with a moral crusade instead of an armed rebellion, prayers instead of machine-gun fire, disdainful silence instead of the fracas of terrorists’ bombs.

While Western Europe had echoed to the harangues of ranting demagogues and shrieking dictators, Gandhi had stirred the multitudes of the world’s most populous area without raising his voice. It was not with the promise of power or fortune that he had summoned his followers to his banner, but with a warning: ‘Those who are in my company must be ready to sleep upon the bare floor, wear coarse clothes, get up at unearthly hours, subsist on uninviting, simple food, even clean their own toilets.’ Instead of gaudy uniforms and jangling medals, he had dressed his followers in clothes of coarse, homespun cotton. That costume, however, had been as instantly identifiable, as psychologically effective in welding together those who wore it, as the brown or black shirts of Europe’s dictators.

His means of communicating with his followers were primitive. He wrote much of his correspondence himself in longhand, and he talked: to his disciples, to prayer meetings, to the caucuses of his Congress Party. He employed none of the techniques for conditioning the masses to the dictates of a demagogue or a clique of ideologues. Yet, his message had penetrated a nation bereft of modern communications because Gandhi had a genius for the simple gesture that spoke to India’s soul. Those gestures were all unorthodox. Paradoxically, in a land ravaged by cyclical famine, where hunger had been a malediction for centuries, the most devastating tactic Gandhi had devised was the simple act of depriving himself of food – a fast. He had humbled Great Britain by sipping water and bicarbonate of soda.

God-obsessed India had recognized in his frail silhouette, in the instinctive brilliance of his acts, the promise of a Mahatma – a Great Soul – and followed where he’d led. He was indisputably one of the galvanic figures of his century. To his followers, he was a saint. To the British bureaucrats whose hour of departure he’d hastened, he was a conniving politician, a bogus Messiah whose non-violent crusade always ended in violence and whose fasts unto death always stopped short of death’s door. Even a man as kind-hearted as Wavell detested him as a ‘malevolent old politician … Shrewd, obstinate, domineering, double-tongued’, with ‘little true saintliness in him’.

Few of the English who’d negotiated with Gandhi had liked him; fewer still had understood him. Their puzzlement was understandable. He was a strange blend of great moral principles and quirky obsessions. He was quite capable of interrupting their serious political discussions with a discourse on the benefits of sexual continence or a daily salt and water enema.

Wherever Gandhi went, it was said, there was the capital of India. Its capital this New Year’s Day was the tiny Bengali village of Srirampur where the Mahatma lay under his mudpacks, exercising his authority over an enormous continent without the benefit of radio, electricity or running water, thirty miles by foot from the nearest telephone or telegraph line.

The region of Noakhali in which Srirampur was set, was one of the most inaccessible in India, a jigsaw of tiny islands in the waterlogged delta formed by the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers. Barely forty miles square, it was a dense thicket of two and a half million human beings, 80% of them Moslems. They lived crammed into villages divided by canals, creeks and streams, reached by rowing-boat, by hand-poled ferries, by rope, log or bamboo bridges swaying dangerously over the rushing waters which poured through the region.

New Year’s Day 1947 in Srirampur should have been an occasion of intense satisfaction for Gandhi. He stood that day on the brink of achieving the goal he’d fought for most of his life: India’s freedom.

Yet, as he approached the glorious climax of his struggle, Gandhi was a desperately unhappy man. The reasons for his unhappiness were everywhere manifest in the little village in which he’d made his camp. Srirampur had been one of the unpronounceable names figuring on the reports arriving almost daily on Clement Attlee’s desk from India. Inflamed by fanatical leaders, by reports of Hindus killing their coreligionists in Calcutta, its Moslems, like Moslems all across Noakhali, had suddenly turned on the Hindu minority that shared the village with them. They had slaughtered, raped, pillaged, and burned, forcing their neighbours to eat the flesh of their Sacred Cows, sending others fleeing for safety across the rice paddies. Half the huts in Srirampur were blackened ruins. Even the shack in which Gandhi lay had been partially destroyed by fire.

The Noakhali outbursts were isolated sparks but the passions which had ignited them could easily become a firestorm to set the whole sub-continent ablaze. Those horrors, the outbursts which had preceded them in Calcutta and those which had followed to the north-west in Bihar where, with equal brutality, a Hindu majority had turned on a Moslem minority, explained the anxiety in Attlee’s conversation with the man he urgently wanted to dispatch to New Delhi as Viceroy.

They also explained Gandhi’s presence in Srirampur. The fact that, as their hour of triumph approached, his countrymen should have turned on each other in communal frenzy, broke Gandhi’s heart. They had followed him on the road to independence, but they had not understood the great doctrine he had enunciated to get them there, non-violence. Gandhi had a profound belief in his non-violent creed. The holocaust the world had just lived, the spectre of nuclear destruction now threatening it, were to Gandhi the conclusive proof that only non-violence could save mankind. It was his desperate desire that a new India should show Asia and the world this way out of man’s dilemma. If his own people turned on the doctrines he’d lived by and used to lead them to freedom, what would remain of Gandhi’s hopes? It would be a tragedy that would turn independence into a worthless triumph.

Another tragedy, too, threatened Gandhi. To tear India apart on religious lines would be to fly in the face of everything for which Gandhi stood. Every fibre of his being cried out against the division of his beloved country demanded by India’s Moslem politicians, and which many of its English rulers were now ready to accept. India’s people and faiths were, for Gandhi, as inextricably interwoven as the intricate patterns of an oriental carpet.

‘You shall have to divide my body before you divide India,’ he had proclaimed again and again.

He had come to the devastated village of Srirampur in search of his own faith and to find a way to prevent the disease from engulfing all India. ‘I see no light through the impenetrable darkness,’ he had cried in anguish as the first communal killings had opened an abyss between India’s Hindu and Moslem communities. ‘Truth and non-violence to which I swear, and which have sustained me for fifty years, seem to fail to show the attributes I have ascribed to them.’

‘I have come here,’ he told his followers, ‘to discover a new technique and test the soundness of the doctrine which has sustained me and made my life worth living.’

For days, Gandhi wandered the village, talking to its inhabitants, meditating, waiting for the counsel of the ‘Inner Voice’ which had so often illuminated the way for him in times of crisis. Recently, his acolytes had noticed he was spending more and more time on a curious occupation: practising crossing the slippery, rickety, log bridges surrounding the village.

That day, when he had finished with his mudpack, he called his followers to his hut. His ‘Inner Voice’ had spoken at last. As once ancient Hindu holy men had crossed their continent in barefoot pilgrimage to its sacred shrines, so he was going to set out on a Pilgrimage of Penance to the hate-wasted villages of Noakhali. In the next seven weeks, walking barefoot as a sign of his penitence, he would cover 116 miles, visiting 47 of Noakhali’s villages.

He, a Hindu, would go among those enraged Moslems, moving from village to village, from hut to hut, seeking to restore with the poultice of his presence Noakhali’s shattered peace.

Because this was a pilgrimage of penance, he decreed he wanted no other companion but God. Only four of his followers would accompany him. They would live on whatever charity the inhabitants of the villages they visited were ready to offer them. Let the politicians of his Congress Party and the Moslem League wrangle over India’s future in their endless Delhi debates, he said. It was, as it always had been, in India’s villages that the answers to her problems would have to be found. ‘This,’ he said, ‘would be his “last and greatest experiment.” If he could “rekindle the lamp of neighbourliness”, in those villages cursed by blood and bitterness, their example might inspire the whole nation.’ Here in Noakhali, he prayed, he could set alight again the torch of non-violence and conjure away the spectre of communal warfare which was haunting India.

His party set out at dawn. Gandhi’s pretty nineteen-year-old great-niece Manu had put together his spartan kit: a pen and paper, a needle and thread, an earthen bowl and a wooden spoon, his spinning-wheel and his three gurus, a little ivory representation of the three monkeys who ‘hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil’. She also packed in a sack the books that reflected the eclecticism of the man marching into the jungle: the Bhagavad-Gîtâ, a Koran, the Practice and Precepts of Jesus, and a book of Jewish thoughts.

With Gandhi at their head, the little band marched over the dirt paths, past the ponds and groves of betel and coconut palms to the rice paddies beyond. The villagers of Srirampur rushed for a last glimpse of this bent 77-year-old man striding off with his bamboo stave in search of a lost dream.

As Gandhi’s party began to move out of sight across the harvested paddies, the villagers heard him singing one of Rabindranath Tagore’s great poems set to music. It was one of the old leader’s favourites, and as he disappeared they followed the sound of his high-pitched, uneven voice drifting back across the paddies.

‘If they answer not your call,’ he sang, ‘walk alone, walk alone.’

The fraternal bloodshed Gandhi hoped to check had for centuries rivalled hunger as India’s sternest curse. The great epic poem of Hinduism, the Mahabharata, celebrated an appalling civil slaughter on the plains of Kurukshetra, north-west of Delhi, 2500 years before Christ. Hinduism itself had been brought to India by the Indo-European hordes descending from the north to wrest the sub-continent from its semi-aboriginal Dravidian inhabitants. Its sages had written their sacred vedas on the banks of the Indus centuries before Christ’s birth.

The faith of the Prophet had come much later, after the cohorts of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane had battered their way down the Khyber Pass to weaken the Hindu hold on the great Gangetic plain. For two centuries, the Moslem Moghul emperors had imposed their sumptuous and implacable rule over most of India, spreading in the wake of their legions the message of Allah, the One, the Merciful.

The two great faiths thus planted on the sub-continent were as different as could be found among the manifestations of man’s eternal vocation to believe. Where Islam reposed on a man, the Prophet, and a precise text, the Koran, Hinduism was a religion without a founder, a revealed truth, a dogma, a structured liturgy or a churchly establishment. For Islam, the Creator stood apart from his creation, ordering and presiding over his work. To the Hindu, the Creator and his creation were one and indivisible, and God a kind of all pervading cosmic spirit to whose manifestations there would be no limit.

The Hindu, as a result, worshipped God in almost any form he chose: in animals, ancestors, sages, spirits, natural forces, divine incarnations, the Absolute. He could find God manifested in snakes, phalli, water, fire, the planets and the stars.

To the Moslem, on the contrary, there was but one God, Allah, and the Koran forbade the Faithful to represent him in any shape or form. Idols and idolatry to the Moslem were abhorrent; paintings and statues blasphemous. A mosque was a spare, solemn place in which the only decorations permitted were abstract designs and the repeated representations of the 99 names of God.

Idolatry was Hinduism’s natural form of expression and a Hindu temple was the exact opposite of a mosque. It was a kind of spiritual shopping centre, a clutter of Goddesses with snakes coiling from their heads, six-armed Gods with fiery tongues, elephants with wings talking to the clouds, jovial little monkeys, dancing maidens and squat phallic symbols.

Moslems worshipped in a body, prostrating themselves on the floor of the mosque in the direction of Mecca, chanting in unison their Koranic verses. A Hindu worshipped alone with only his thoughts linking him and the God he could select from a bewildering pantheon of three to three and a half million divinities. It was a jungle so complex that only a handful of humans who’d devoted their lives to its study could find their way through it. At its core was a central trinity: Brahma, the Creator; Shiva, the Destroyer; Vishnu, the Preserver – positive, negative, neutral forces, eternally in search, as their worshippers were supposed to be, of the perfect equilibrium, the attainment of the Absolute. Behind them were Gods and Goddesses for the seasons, the weather, the crops, and the ailments of man, like Maryamma, the smallpox Goddess revered each year in a ritual strikingly similar to the Jewish Passover.

The greatest barrier to Hindu-Moslem understanding, however, was not metaphysical, but social. It was the system which ordered Hindu society, caste. According to Vedic scripture, caste originated with Brahma, the Creator. Brahmins, the highest caste, sprang from his mouth; Kashtriayas, warriors and rulers, from his biceps; Vaishyas, traders and businessmen, from his thigh; Sudras, artisans and craftsmen, from his feet. Below them, were the outcasts, the Untouchables who had not sprung from divine soil.

The origins of the caste system, however, were notably less divine than those suggested by the Vedas. It had been a scheme employed by Hinduism’s Aryan founders to perpetuate the enslavement of India’s dark, Dravidian populations. The word for caste, varda, meant colour, and centuries later, the dark skins of India’s Untouchables gave graphic proof of the system’s real origins.

The five original divisions had multiplied like cancer cells into almost 5000 sub-castes, 1886 for the Brahmins alone. Every occupation had its caste, splitting society into a myriad of closed guilds into which a man was condemned by his birth to work, live, marry and die. So precise were their definitions that an iron smelter was in a different caste to an ironsmith.

Linked to the caste system was the second concept basic to Hinduism, reincarnation. A Hindu believed his body was just a temporary garment for his soul. Each life was only one of his soul’s many incarnations in its journey through eternity, a chain beginning and ending in some nebulous merger with the cosmos. The Karma, the accumulated good and evil of each mortal lifetime, was a soul’s continuing burden. It determined whether, in its next incarnation, that soul would move up or down in the hierarchy of caste. Caste had been a superb device to perpetuate India’s social inequities by giving them divine sanction. As the Church had counselled the peasants of the Middle Ages to forget the misery of their lives in the contemplation of the hereafter, so Hinduism had for centuries counselled the miserable of India to accept their lot in humble resignation as the best assurance of a better destiny in their next incarnation.

To the Moslems to whom Islam was a kind of brotherhood of the Faithful, that whole system was anathema. A generous, welcoming faith, Islam’s fraternal embrace drew millions of converts to the mosques of India’s Moghul rulers. Inevitably, the vast majority of them were Untouchables, seeking in the brotherhood of Islam an acceptance their own faith could offer them only in some distant incarnation.

With the collapse of the Moghul Empire at the beginning of the eighteenth century, a martial Hindu renaissance spread across India, bringing with it a wave of Hindu-Moslem bloodshed. Britain’s conquering presence had forced its Pax Britannica on the warring sub-continent, but the mistrust and suspicion in which the two communities dwelt remained. The Hindus did not forget that the mass of Moslems were the descendants of Untouchables who’d fled Hinduism to escape their misery. Caste Hindus would not touch food in the presence of a Moslem. A Moslem entering a Hindu kitchen would pollute it. The touch of a Moslem’s hand could send a Brahmin shrieking off to purify himself with hours of ritual ablutions.

Hindus and Moslems shared the villages awaiting Gandhi’s visit in Noakhali, just as they shared the thousands of villages all through the northern tier of India in Bihar, the United Provinces, the Punjab. They dwelt, however, in geographically distinct neighbourhoods. The frontier was a road or path, frequently called the Middle Way. No Moslem would live on one side of it, no Hindu on the other.

The two communities mixed socially, attending each other’s feasts, sharing the poor implements with which they worked. Their intermingling tended to end there. Intermarriage was almost unknown. The communities drew their water from separate wells and a caste Hindu would choke before sipping water from the Moslem well perhaps yards from his own. In the Punjab, what few scraps of knowledge Hindu children acquired came from the village Pandit who taught them to write a few words in Punjabi in mud with wheat stalks. The same village’s Moslem children would get their bare education from a sheikh in the mosque reciting the Koran in a different language, Urdu. Even the primitive drugs of cow’s urine and herbs with which they struggled against the same diseases, were based on different systems of natural medicine.