Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

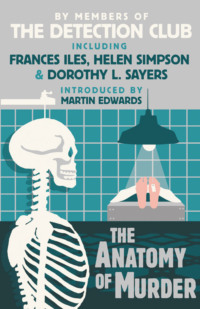

Kitabı oku: «The Anatomy of Murder», sayfa 2

PART I

DEATH OF HENRY KINDER

by Helen Simpson

DEATH OF HENRY KINDER

CRIME in Australia: those three words start, in the mind of the reader, a train of association which runs through the gold fields of Ballarat to end in the explosive sentiment of Rolf Boldrewood’s Robbery Under Arms. Crime in Australia puts on a red shirt, gallops gallantly, tackles its trackers in the open air. The kindly spaces of a new country afford the criminal a chance, if he escapes, to make good; finally if he should have the bad luck to encounter Sherlock Holmes during his retirement, that finely tempered instrument of justice will say: “God help us! Why does Fate play such tricks with poor helpless worms?”1 and refrain from prosecution.

So much for the popular conception. Actually, crime in Australia follows much the same patterns as crime elsewhere. Murders are committed for the same motives, gain, elimination, and fear; and the more sensational of these are perpetrated by individuals whose surroundings would seem to guarantee their respectability.

Witness the case of that highly reputable chemist, John Tawell, of Hunter Street, Sydney, who having built a chapel for the Society of Friends, and publicly emptied six hundred gallons of rum into Sydney Harbour as an object lesson in temperance, in 1845 murdered his mistress with prussic acid and was hanged. Witness half a dozen other urban crimes, about which hangs no scent of the scrub or of saddle-leather; in particular, the murder of Henry Kinder, principal teller in the City Bank of Sydney, sufficiently well-to-do, living in a decent suburb on the North Shore of Sydney Harbour. This crime hath had elsewhere his setting; it is a domestic drama such as might have been played in any Acacia Avenue of the old world. True, the assassin had at one time some notion of dressing the part, and purchased a red Crimean shirt, on which bloodstains would not be conspicuous; but the crime itself was committed, so far as can be ascertained, in the ordinary sombre undress of a dentist.

II

On October 2, 1865, the news of Henry Kinder’s suicide startled his circle of respectable friends. His tendency to drink was known, but that he should have had le vin triste to this degree was unsuspected; the more so that he had no troubles about money, and seemed to be happy in his family life. The inexplicable suicide became a topic of conversation in Sydney. Nobody had realized that Kinder was the kind of man to drink himself into delirium or to utter violent threats against himself and his family; yet that he had done so his wife declared at the inquest, and her evidence was corroborated. The coroner directed his jury to bring in a verdict of suicide during temporary insanity, and Kinder was buried with every testimony of regret and respect. Mrs. Kinder retired to Bathurst, where she took up life again with her parents, who kept a small general shop. The talk, for a time, died down.

But not for long. The jury found that the deceased had met his death “by the discharge of a pistol with his own hand.” The How, thus was answered; the Why, despite evidence of his drinking, remained mysterious. It was this last question which worked in the minds of Henry Kinder’s fellow-citizens, and there were conjectures in the clubs that a certain Louis Bertrand, who had been heard making extravagant statements concerning his relations with the Kinder family, might be able to answer it. These statements the police investigated, with the result that six weeks after the inquest, on November 29th, Louis Bertrand and his wife Jane were charged before the magistrates at the Water Police Court, Sydney, with the wilful murder of Henry Kinder; Helen Mary Kinder, the dead man’s widow, appearing as accessory to the fact.

Bertrand was brought to court from gaol, where he had been serving a sentence for using threatening language. The warrant was read to him, it seems, in his cell. “Rather a heavy charge,” was his comment. The detective inquired if he should take that by way of answer. “Am I on my trial now?” the accused asked sardonically; and being told that the officer was only stating the charge, Bertrand answered emphatically: “Then my reply to it is—not guilty.” This he repeated in the dock. His wife echoed him. Mrs. Kinder, brought down in custody from Bathurst to Sydney, indignantly denied any knowledge of the crime. The magistrates heard these answers, refused bail, and at the request of the police remanded the prisoners until the Monday following, December 4th.

At that hearing nothing new was revealed, except the ages of the accused; Bertrand was 25 years old, his wife 21, and Mrs. Kinder, who refused to give the year of her birth, was stated to be apparently about 30 years of age. They were remanded again until December 7th.

III

On December 7th the case for the Crown was opened by Mr. Butler; and it at once became evident that Mrs. Kinder was on her trial, not as accessory to a murder, but as an adulteress. It was “morally impossible,” said counsel, to commit the other prisoners without committing her also. The evidence would consist, in the main, of admissions made by the Bertrands, with other circumstances, all of which were capable of proof. The motive was easily discoverable. Certain writings, now in the hands of the police, would afford evidence that a personal intimacy existed between Bertrand and Mrs. Kinder; and, said counsel, with the ripe conviction of all Sydney’s gossips behind him, “such an intimacy could not exist without furnishing a clue to the imputed crime.”

Counsel proposed to establish that there had been illicit intercourse between Louis Bertrand and Helen Kinder before the death of the latter’s husband; that it had been Bertrand’s design to divorce his own wife; and that Henry Kinder had been killed in order that Mrs. Kinder might be free to marry Bertrand.

Detective Richard Elliott was his first witness. This officer produced a packet containing letters found in a drawer in Bertrand’s house; they were unsigned, but appeared to be in the handwriting of Mrs. Kinder. He produced a diary found in an unlocked drawer in Bertrand’s bedroom. He produced a bottle labelled tincture of belladonna, and a phial labelled chloride of zinc; together with a pistol and powder flask, a box containing caps, a tomahawk, a screw such as might be used for the nipple of a pistol, a phial of white powder, unlabelled, and two books. There was a brief interlude while prisoners’ counsel elicited from the detectives concerned the fact that they had not been impeded or hindered in their search; Mrs. Kinder had even asked that a certain desk, to which she could not find the key, should be broken open. She told the officer that she kept none of Mr. Bertrand’s letters, but always burned them after she had read them. He found one, however, dated October 28th, signed by Bertrand. He also found, in a box which contained children’s clothing, a pistol; the pistol, Mrs. Kinder told him, with which her husband had shot himself. These cross-examinations over, Mr. Butler began to read from the letters of Helen Maria Kinder.

There were nine of them; and a more curious set of documents can seldom have been produced in evidence. There is not space to quote them fully. The picture they offer is of a woman alternately cautious and abandoned. News of her three children, of churchgoing, and of the life in a small country town make up the chief of their matter, but there are outbursts which leave no doubt as to her relationship with Bertrand. It is noticeable that these grow more frequent as she becomes more bored with the life of a small country town, unfriendly to a newcomer without money, inquisitive, uncharitable, and remote from the standards of a wider world. From first to last there is no mention of her husband, and no reference which would imply that she had any knowledge of how he came by his death.

The first letter, which begins: “My dear friend,” and ends: “Kindest regards to yourself and all the family, and believe me ever to remain truly yours, Ellen Kinder,” is by no means compromising. Fatigue—she had had two days’ coach journey, looking after her three children the while—may possibly account for the non-committal tone of it. “I do not think I was ever so tired in my life; I trust I may never again experience such utter prostration.” Bathurst appeared dreadfully dull, but she would not judge hastily. In the morning she intended going to church to have a look at “the natives”—not aborigines, but such society as the town offered. This is all, except that she sends her “kind love” to Jane, Bertrand’s wife.

The next letter, written just a week later, is the queerest mixture of passion and practicality.

MY DEAREST DARLING LOVE,

I have just received your dear, kind, and most welcome letter. Oh, darling, if you could but know how my heart was aching for a word of love from you. Dear, dear lover, your kind loving words seemed to have filled a void in my heart. I cannot convey to you in words the intense comfort your letter is to me. It has infused new life into my veins.…

I suppose you must not be ashamed of our poor home when you come up, darling, but I know that will make no difference to you. If I lived in a shanty it would be all the same, would it not? Now about your coming up, dear darling. How I should like to see your dear face, and to have a long talk with you about affairs in general. But, my own love, I fear if you were to come just now you would not find it pay you. Everything is so dull, and what I fear more is that people to whom you owe money would be down on you directly, thinking you were going to run away. Dear darling, all this advice goes sadly against the dictates of my own heart, for my spirit is fairly dying for you. A glimpse of you, oh dearest, dearest, what would I not give to be taken to your heart if only for a moment; I think it would content me.

It is no use, dear. Your love is food—nourishment to me. I cannot do without it. I tried to advise you for the best, but I cannot. I cry out in very bitterness. If I could only be near you, only see you at a distance once again, I think I could bear myself. I believe, darling, if our separation is for long, I shall go out of my mind.…

How is Jane? What is the matter? It is of no use to say that I am grieved at her being laid up; that would be a mere farce between you and I. As to her assertions with regard to Mr. Jackson, I shall not answer them; for if I am to be taken to task about all she may choose to say about me I shall have enough to do.… I know her, and you ought to by this time. If you allow everything she may say to influence you against me, I have done, but, darling, I am yours. I leave my conduct to be judged by you as you think fit. There let the matter rest. It ought never to have been broached.

Mr. Jackson, at the time this letter was written, was serving a sentence of twelve months’ imprisonment for attempting to extort money from Bertrand by threats. (He had written to Bertrand saying that his association with Kinder’s wife was known, and could be proved if Jackson chose to say what he knew.) He was sentenced on the day—October 23rd—that Mrs. Kinder first wrote to Bertrand from Bathurst. He was to be an important witness at the trial, and Mrs. Kinder’s airy “It ought never to have been broached” covers the consciousness that she had in fact lived with Jackson as his mistress. The document ends with an account of her family’s money affairs. Her father’s shop did not prosper, her mother had only £50 coming in yearly from some small property in New Zealand. They were not very easily able to keep four extra persons for an indefinite time. Could Bertrand discover some opening for the family in Sydney? An hotel perhaps? “I am always well when I get a letter to strengthen me.” She ends: “God bless you. Good night, darling love, and plenty kisses from your own darling Child.” In the third letter, dated November 9th, she is, as ever, preoccupied equally with the future and the present. She has tried for a governess’s situation, but times are bad. The clergyman has come to call. Her youngest child, Nelly, would soon be walking. She would like to get into a dressmaking business in Sydney. The thought of seeing him again sends her blood “gurgling” in her veins. “God for ever bless you and preserve you from harm, and preserve your dear children.”

But Mrs. Kinder’s mother was becoming suspicious, and, it would seem, not only of the relationship between her daughter and the Sydney dentist.

She advises me to be careful what we write, as she says there are many reports with regard to us in Sydney, and that the detectives have power, and might use it if they thought to find out anything by opening our letters. I was not aware they had that power; it is only in case of there being anything suspicious with regard to people.

Mamma, in fact, read her daughter a lecture, refusing to countenance “anything wrong”. With all this, there was no question of turning away Mrs. Kinder and her children. “As far as anything in the shape of love and affectionate welcome goes, to the last crust they have I can depend.” But the takings of the shop were never more than five shillings a day, and sometimes not sixpence. She could not go on being a burden; “I would rather be a common servant.” Upon this situation she reflects:

How black everything looks, Lovey, does it not? Our good fortune seems to be deserting us.

Was this a reference to the death of Kinder, an affair surely of management rather than luck? If so, it is the only reference in the letters, which run to some ten thousand words. They keep their pattern of lamentations, shrewd planning, passion, and where her family is concerned a kind of affectionate independence, together with one or two items of actual news. She had become a seamstress to help the family finances; her father was off to New Zealand again; her brother Llewellyn was staying in Bertrand’s house; she was determined to come to Sydney. The last letter, dated November 21st, ends:

When I think I shall be with you in less than a week—oh, this meeting, love, oh, I shall go mad; it is too delicious to dream of; oh, let it be in reality, darling, do, do. My feelings will burst, but still, dear one, I trust you will do what is best for us in the end, I would say——

The newspaper report says: “Remainder illegible.”

IV

These were the first documents read by Mr. Butler, the Crown counsel. It is odd to picture the scene. The Water Police Court is not an impressive or a roomy building. The month was December, when Sydney is beginning to feel the weight of summer. There is great humidity, heat lies upon the town like a blanket, and all the distances dance. To Bertrand, even the stuffy court must have seemed spacious compared with his cell in Darlinghurst Gaol. Mrs. Kinder, brought down from the greater heats of Bathurst, may have found the air of Sydney grateful. Only Mrs. Bertrand, poor Jane, coming to the box from her pleasant house in Wynyard Square, must have felt bitterly the confinement and the heat. Mr. Butler, who had already spoken and read for some hours, returned to the charge in the afternoon; and when the diary’s handwriting had been identified by Bertrand’s assistant, Alfred Burne, he began, in the passionless tones congruous with his duty, to read aloud the diary of Louis Bertrand.

October 26th. Thursday.

Lonely! Lonely! Lonely! She is gone—I am alone. Oh, my God, did I ever dream or think of such agony? I am bound to appear calm, so much the worse. I do so hate mankind. I feel as if every kindly feeling had gone with her. Ellen, dearest Ellen, I thank, I dare to thank God, for the happiness of our last few moments. Surely He could not forsake us, and yet favour us as He has done. Tears stream from my eyes, they relieve the burning anguish of my bursting heart. Oh, how shall I outlive twelve long months! Child, I love thee passionately—aye, madly. I knew not how much until thou wert gone. And yet I am calm. ’Tis the dead silence which precedes the tempest.…

Do not rouse the demon that I know lies dormant in me. Beware how you trifle with my love. I am no base slave to be played with or cast off as a toy. I am terrible in my vengeance; terrible, because I call on the powers of hell to aid their master in his vengeance. God, what am I saying? Do not fear me, darling love. I would not harm thee, not thy dear self, but only sweep away as with a scimitar my enemies or those who step between my love and me. Think kindly of me—of my great failings. See what I have done for thee, for my, for our love.

Such were the first paragraphs of this document in madness. The diary was faithfully kept, reflecting Bertrand’s love, his fantasies, his finances, and his health. In itself it would be enough, nowadays, to support a defence of insanity. But the magistrates of 1865 took it seriously, and Sydney shuddered as the newspapers reported it piecemeal. The journal covers only twenty-four days, from the date on which he parted from Mrs. Kinder to that on which he was summoned on the charge of writing a threatening letter to a woman, Mrs. Robertson. His triumph over Jackson makes odd reading, when it is considered that three weeks later both were serving sentences for a parallel offence.

In the train I borrowed half the Empire, which contained this paragraph: “Francis Arthur Jackson, convicted of sending a threatening letter to Henry L. Bertrand with the intent to extort money, sentenced to 12 months’ hard labour in Parramatta Gaol.” It pleased me. I am satisfied. Thus once more perish my enemies. He is disposed of for the present.

On the same page:

I feel that I love you as mother, sister, husband, brother, all combined. What work I have before me, God only knows, but I will call His love to help me, and strive to do right. I feel I shall. Thy dear devoted love will save me. I know it will, and we may yet be good and happy together.

An echo of the gossip which was alive concerning him may be found in the brief statement which follows: “Am doing no business whatever.” He was ill, too, with some internal trouble, concerning which he makes this reflection:

I am now, by my own agonies, paying a debt to retributive justice; how and what I have made others suffer, God only knows; but if I have, I richly deserve all I now feel; and you, my love, have you not done the same?

’Tis strange our two natures are so much alike. I love a companion who can understand my sentiments, respond to the very beating of my heart, help me to think, to plan, and by clear judgment advise me on worldly affairs. A woman is not a toy. Women are as men make them. I have found, from experience, that half the trouble women give their husbands is caused by the husbands themselves—sometimes directly, but often from some indirect cause that might have been avoided if the man had used even moderate care in the guidance of the being sacredly entrusted to his charge.… One more day stolen from fate.

This was Friday, October 27th. Two days later he was up and about, spending an artistic rather than a conventional Sunday.

I awoke this morning too late for church—I did not dress or shave. I fear, my dear Nelly, that not having you to fascinate I shall become slovenly and untidy, for if I consulted my own feelings I should not dress at all.

I want fame, as well as wealth and power, and as usual little Bertrand must have his way. You know he is a spoilt child, spoilt in more ways than one. So as I was saying, I must have fame, fortune and power, as well as the most ardent, pure, passionate, and devoted love of the most fascinating, amiable and best of women that the world at present contains. There, if this is not flattery I do not know what is; but it is the truth—at least, I think it is the truth to the best of my belief, as we say in court. Oh, I must not speak of courts; we have had enough of them, at least for the present.

At this time he set to work to model two salt-cellars for the third Victorian exhibition of 1866; Fijians, “kneeling in a graceful attitude”, holding pearl shells, upon stands “emblematical of the sea shore”; the spoons to consist of paddles, “formed of some sort of shell, small of course”; all to be cast in solid silver, frosted. “Dearest, it is for thee that I toil.” He turned from this work to conversations with his sister, who recommended a divorce as being the kindest thing that he could do for poor Jane; and to his diary, intended for Ellen’s reading later on, when the period of separation was over. Certain further passages of this were read with emphasis by Mr. Butler.

I should feel ashamed of my love, of what I have done for it, if it were no different from that of others. That is our only excuse, whether on earth or Heaven, for what we have accomplished.… Let us not be cowed or terrified at aught that besets us. I warned you what to expect, and, dearest, for the greatness of our love for one another, surely we can bear fifty times more than we have to bear. I do not fear the result. To me the end is clear and palpable, I am sure of it; I never yet failed in my life.

November 8th.

Thank God, another day gone. However will a twelvemonth pass? God only knows. My heart grows sick and faint when I look into the future. Oh, God, is this Thy retribution for our sins? Did I flatter myself that the Almighty would let me—a wretch like me—go unpunished; but I tell thee, fate, I defy thee. I feel as though my heart were rent in pieces, and then dark thoughts obtrude themselves before me, fiends rise and mock me; they point to a gate, a portal through which I feel half inclined to go; but not yet.. What would my love do without me? … No matter what thou hast been, my child, I hold thee as a true, virtuous wife to me, for you have been true to me, my dearest love.

Bertrand went on this day, Wednesday to see one of the directors of the City Bank, Kinder’s employers, who gave him news. A temporary cross was to be put on “poor Harry’s grave” in New Zealand (whence the Kinders had come to New South Wales); “they think that Harry did not intend to kill himself, but only to frighten his wife.” When Bertrand suggested that possibly Mrs. Kinder might come to Sydney to find work, the director was evasive and recommended that “old affairs should blow over”. Next day Mrs. Kinder’s father, Mr. Wood, came to see him, and they walked down together to the ferry wharf, and travelled over to the North Shore to see a mutual friend, De Fries.

I felt very strange. This is the first time I have been to the Shore since poor Harry’s funeral. I am standing on the deck, my face turned towards the little house with the two chimneys, as I used to do when on wings of love I flew to my beloved.… How horribly jealous I was, I was mad … surely there can be no worse hell than our own conscience.

Mr. De Fries it was who gave Bertrand the first warning that all was not well, and that Sydney, unlike New Zealand, was beginning to be suspicious of Kinder’s suicide. De Fries spoke reasonably; said that he had watched the affair growing, and that he had a high regard for Jane. He told Bertrand that Mrs. Kinder cared nothing for him, that she was a calculating woman, while Jane was an affectionate and true one. He felt for Bertrand, he told him, like a brother, and exhorted him, if he cared for his happiness in this world and his welfare in the next, not to yield to temptation. The diarist listened attentively, but coming home, broke Jane’s fan in a passion. That he believed, or rather, that he knew De Fries to be speaking the truth, is shown in a paragraph which ends the entry for this day:

November 12th.

Be she as wicked as Satan, as vile and wily as the serpent, I, even I, will save her, will raise her from the depth of hell. I, Ellen, even I, thy lover, wicked as I am, will be a Saviour to thee. Dear, sweet, loved Ellen, the more they oppose us the greater will be my power of resistance. Poor fools, to try and thwart my will. Indeed, if thou hast me for an enemy—I who value human life as I value weapons, to be used when required and thrown away or destroyed; some, of course, kept for future use if necessary. Beware! If I have my way in this, if I obtain this sole object of my being I feel that I shall be reclaimed; but if not, no matter from what cause, Heaven help the world, oh! I shall indeed be revenged.

Next, Mrs. Robertson, a friend to both parties, issued her warning. She advised Bertrand to have no more to do with Mrs. Kinder; and told him frankly that she would not have Ellen in her house, were she to come to Sydney. Again he listened patiently, and again there followed an outburst, a frantic act of faith.

DEAR, DEAR CHILD,

I trust that she is truly penitent for what she has done, and that with me she will be in future a truly good and virtuous woman. Why do people try to torture me thus? God knows I have misery and wretchedness enough. I am prepared for the worst and God help the world if this my forlorn hope fails. To hear her [Ellen] spoken of as bad, is sufficient to upset my intellect.…

Ellen, my dear love, I must be near you. I want to look into those dear wicked eyes and I know they cannot, will not, deceive me. If I have, like others, cause to repent what I have done—I must drop this painful subject or I shall be ill—it will unman me—unfit me for the battle I am fighting. Enough excitement of mind for one day. Adieu, my thoughts. Adieu, my own Ellen.

Louis.

It is not quite the last entry, but it is the most revealing of all. The exaltation was fading; the way to happiness, which had seemed so clear and sure, was obscured. Bertrand knew that Mrs. Kinder had been the mistress of at least one of his acquaintances; that there had been other men in New Zealand he conjectured. He was tormented; the journal plainly shows him twisting away from inescapable conclusions, and so towards madness. When Mr. Butler laid down the notebook which gave such an intimate picture of Bertrand’s mind, he had proved to the public’s satisfaction that Bertrand had good reason to wish Kinder out of his way.

V

But Kinder met his death by the firing of a pistol close to his ear. Whose finger pulled the trigger of that pistol? Mr. Butler recalled Bertrand’s assistant, Alfred Burne, who, after telling how he delivered letters from Bertrand to Mrs. Kinder, and how she had often stayed in the surgery at night, gave the following account of some remarkable expeditions:

About six weeks previous to Kinder’s death he [Bertrand] asked me where I could get a boat to hire. I mentioned Buckley’s among others. We went rowing the following night about 12 o’clock, to the North Shore as far as Kinder’s house, opposite to the bedroom window on which the moon was shining. He said: That is his bedroom. He did not then say what was the purpose of his visit. He did not go in. He said the moon was too strong, he had come too early.… We went back again three nights after, taking a boat from the same place, and went up to the house. As we went over he said it was very likely that next morning Kinder would be found dead in his bed, having committed suicide, and that letters from Jackson would be found in his hand.

They arrived at Kinder’s house about one in the morning. Bertrand took off his boots, gave them to Burne to hold, and climbed into the house by the dining-room window. He came back much later—Burne fell asleep meanwhile—angry because Kinder would not drink his beer, and consequently was awake. “We had drugged it,” said Bertrand.

Some days, about a week later, Bertrand produced in his surgery a hatchet, and asked Burne to bore a hole in the handle so that he might tie it under his coat by a string. A young man, Ranclaud, who was staying in the house, asked what he meant to do with it. Bertrand answered abruptly, and with no care for probabilities, that he was going fishing, and went out with Burne to their hired boat. On the way, he said that Kinder had insulted him; that he was going to knock Kinder’s brains out first, and then get a divorce from Mrs. Bertrand.

I remarked what object could he have in putting Mr. Kinder out of the way when Mrs. Kinder was as good as a wife to him. He said he wished to have Mrs. Kinder all to himself.

On this occasion Bertrand entered the house by the same window, but returned soon, saying that Jackson and Mrs. Kinder’s brother Llewellyn were sleeping in the house, and as the boards creaked he did not think it safe.

COUNSEL: Safe to do what?

BURNE: To murder Mr. Kinder, as I understood.

A week later the expedition was repeated, but in remarkable conditions. Bertrand shaved himself at midnight; then blacked his face, donned a mask and the red Crimean shirt, topped this disguise with a slouch hat, took off his boots, drank some brandy, and set out in the boat at about 1.30 in the morning. Burne went with him. Why he should have done so is inexplicable. True, he was in Bertrand’s employ; true, he may not have taken seriously Bertrand’s boasts and threats against Kinder. But he was sufficiently well aware of danger when his own skin was in question.

On these occasions I always carried the hatchet myself; I also used to get him to sit in front of me in the boat for fear of accidents. I made him pull the stroke oar, while I pulled the bow oar, fearing that, taking me by surprise while my back was turned, he might throw me into the water.

That night Bertrand asked Burne to help him when he got inside the house. If Kinder, he said, were to be killed that night, suspicion would inevitably fall on Jackson, who was leaving Sydney next day. The young man answered that it was all too romantic for him, that he had no share in Mrs. Kinder and intended to run no risk. Bertrand at this seemed to abandon his plan, whatever it may have been, and they rowed home. This was the last expedition in the boat.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.