Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Gerald Durrell»

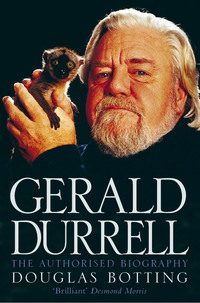

GERALD DURRELL

THE AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY

Douglas Botting

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers in 1999

Copyright © Douglas Boning 1999

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006387305

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2014 ISBN: 9780007381227

Version: 2019-06-10

Praise

Further reviews for Gerald Durrell:

‘Douglas Botting is to be congratulated on Gerald Durrell. He has done a magnificent job in telling the complex story of a complex person, wrinkles and all. Here is your chance to rediscover the man who for over sixty years exasperated and fascinated his friends and fans, giving hope to generations that there was a future for animals, plants and people.’

DAVID BELLAMY, Literary Review

‘The book serves up so much by way of compelling detail that the reader forges happily ahead … [an] affectionate account of a rumbustious figure.’

PENELOPE LIVELY, Daily Telegraph

‘Douglas Botting’s biography of Gerald Durrell is a whacking great book … But then, the environmentalist, naturalist, humorist, bestselling author and adventurer was a whacking great personality. His riotous enjoyment of life and his passion-ate, loving struggle for animal conservation fly off the pages. It’s an absorbing, hugely appealing story.’

New Scientist

‘Botting’s admiration and affection for his subject are infectious.’

Sunday Times

‘An extraordinary story … a biographer’s dream.’

EDWARD MARRIOTT, Evening Standard

‘Douglas Botting quotes continually from unpublished material – letters, journals, diaries – which prove to be a treasure-house of agile and acute observation … [He] is a perceptive, vigorous, unabashed chronicler … at his best in dealing with the complexities of Durrell’s own character and the crises in his life … This is the most enjoyable biography I have read for years.’

J.B. PICK, Scotsman

‘A compelling read.’

DAVID NICHOLSON-LORD, Financial Times

‘Botting gives us a full-on Durrell … a wonderfully detailed account.’

RICHARD D NORTH, Independent

‘Exhaustive research … poignant reading.’

CAROLINE MOOREHEAD, Spectator

‘Absorbing.’

Tatler

‘Gerald Durrell was a man of immense character as this enormous biography testifies … and he shines out of these pages. Botting’s writing style is a delight. He has a wry eye and his own dry wit … He has told a powerful story.’

JULIA LANGDON, The Herald (Glasgow)

‘Wonderfully affectionate account … wonderfully readable.’

CHRISTINE BARKER, Birmingham Post

‘The best parts are the descriptions of furry animals – both Durrell’s and the author’s – which appear on page after page … the book is a love story of a sort.’

ROY HATTERS LEY, Mail on Sunday

‘Joyful reading … Botting is on sure, captivating ground as he relates Durrell’s escapades … a valuable chronology of Durrell’s experiences.’

ROSEMARY GORING, Scotland on Sunday

‘Douglas Botting paints a vivid picture … an excellent reflection of the man behind the magic’

ISOBEL OSMONT, Jersey Evening News

‘This revealing and compulsive biography will inspire many generations to come.’

JOHN BURTON, World Land Trust Review

‘Botting’s biography is vast, vibrant, intense.’

MICK MIDDLES, Manchester Evening News

‘In this superb biography Douglas Botting keeps you turning the pages and even succeeds in conjuring tears at the end. Meticulous research has enabled him to bring us an in-depth picture of the man. It is a measure of its success that I seriously resented having to go to work, or to bed, whilst reading it.’

HILARY PAIPETI, The Corfiot Magazine, Greece

Epigraph

Right in the Hart of the Africn Jungel a small wite man lives. Now there is one rather xtrordenry fackt about him that is that he is the frind of all animals.

From ‘The Man of Animals’ by Gerald Durrell, aged ten

Whoever saves one life,

Saves the world.

The Talmud

When you get to the Pearly Gates and St Peter asks you, ‘Well, what did you do?’ if you can say, ‘I saved a species from extinction,’ I think he’ll say, ‘OK, well, come on in.’

John Cleese

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

EPIGRAPH

PREFACE

PROLOGUE

PART 1: ‘The Boy’s Mad … Snails in his Pockets!’

1 Landfall in Jamshedpur: India 1925–1928

2 ‘The Most Ignorant Boy in the School’: England 1928–1935

3 The Gates of Paradise: Corfu 1935–1936

4 The Garden of the Gods: Corfu 1937–1939

5 Gerald in Wartime: England 1939–1945

6 Odd-Beast Boy: Whipsnade 1945–1946

7 Planning for Adventure: 1946–1947

PART 2: Promise Fulfilled

8 To the Back of Beyond: First Cameroons Expedition 1947–1948

9 In the Land of the Fon: Second Cameroons Expedition 1948–1949

10 New Worlds to Conquer: Love and Marriage 1949–1951

11 Writing Man: 1951–1953

12 Of Beasts and Books: 1953–1955

13 The Book of the Idyll: 1955

14 Man and Nature: 1955–1956

15 ‘A Wonderful Place for a Zoo’: 1957–1959

PART 3: The Price of Endeavour

16 A Zoo is Born: 1959–1960

17 ‘We’re All Going to be Devoured’: Alarms and Excursions 1960–1962

18 Durrell’s Ark: 1962–1965

19 Volcano Rabbits and the King of Corfu: 1965–1968

20 Crack-Up: 1968–1970

21 Pulling Through: 1970–1971

22 The Palace Revolution: 1971–1973

23 Gerald in America: 1973–1974

24 ‘Two Very Lost People’: 1975–1976

25 Love Story: Prelude: 1977–1978

26 Love Story: Finale: 1978–1979

PART 4: Back on the Road

27 A Zoo with a View: 1979–1980

28 Ark on the Move: From the Island of the Dodo to the Land of the Lemur 1980–1982

29 The Amateur Naturalist: 1982–1984

30 To Russia with Lee: 1984–1985

31 Grand Old Man: 1985–1991

PART 5: A Long Goodbye

32 ‘Details of my Hypochondria’: 1992–1994

33 ‘A Whole New Adventure’: 1994–1995

AFTERWORD

THE DURRELL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION TRUST

SOURCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Preface

I met Gerald Durrell only once in the flesh. It was in the early summer of 1989 at the London Butterfly House in Syon Park, where he and his wife Lee ceremonially launched an initiative called ‘Programme for Belize’ – intended to save for posterity a superb tract of tropical forest in the north-east of that country – by releasing newly hatched Belizean butterflies into the Butterfly House. Our encounter afterwards, as Durrell passed down a line of extended hands on his way out through the door, was brief, polite and perfunctory. At this meeting neither he nor I could have dreamed that biographer was meeting biographee. Had we known it, we would have had a lot to talk about. With better luck all round, we might have been talking still.

I thought no more about this until, one scorching late September noon in 1994, I found myself sitting with my elder daughter Kate on the terrace of the White House, Lawrence Durrell’s old pre-war home at Kalami on the north-east coast of Corfu, watching the caïques coming in to the bay one by one, each with its complement of tourists on board. Across the water I could hear the running commentary of the Greek skippers. ‘And now we enter beautiful Kalami Bay,’ they intoned. ‘On your left you will see the famous White House where Gerald Durrell once lived in Corfu and wrote his famous book, My Family and Other Animals …’

Gerald Durrell, of course, had done nothing of the kind. I turned to Kate. ‘That’s all wrong,’ I said. ‘Someone ought to do something to get it right. Come to think of it, someone ought to do something about writing a proper biography of Gerald Durrell.’

Kate, who was a Durrell fan, replied: ‘Perhaps you ought to write it yourself.’

It was not a totally wild idea. I had already written two books about traveller-naturalists, and my recently published biography of the author-naturalist Gavin Maxwell had been well enough received for me to begin to think about writing some kind of sequel. I had read most of Gerald Durrell’s books, I had even reviewed one or two for the national press, I felt I understood his world and mind-set, I had even – dammit! – shaken the man by the hand in the Butterfly House. As soon as I returned to England I phoned Gerald Durrell’s personal assistant at Jersey Zoo, and on his advice wrote to Durrell’s literary agent enclosing a copy of my latest book and, for good measure, proposing myself as her client’s future biographer.

Within a few hours my book was in Durrell’s hands in a London hospital ward, where he lay gravely ill after a major operation. He knew of Gavin Maxwell, of course, and had reviewed Ring of Bright Water for the New York Times. He opened the book and read the first lines of the preface: ‘The sea in the little bay is still tonight and a full moon casts a wan pallor over the Sound and the hills of Skye. A driftwood fire crackles in the hearth of the croft on the beach, and through the open window I can hear all the sounds and ghosts of the night – the kraak of a solitary heron stalking fish in the moonlight at the edge of the shore, a seal singing softly in the bay, the plaintive child-like voice rising and falling like a lullaby in the dark …’ Here in the noisy bedlam of the public ward, a world of bedpans, drips, catheters, trolleys and rubber sheets, of pain, squalor and despair, his weary head sunk deep into his hard starched pillow, his wild white hair strewn about him, he recognised at once a kind of mirror image of his own past life and dreams. He turned the page. ‘A guru of the wilds among a whole generation, Gavin Maxwell was ranked with John Burroughs, W. H. Hudson and Gerald Durrell as one of the finest nature writers of the last hundred years …’

Durrell sat up a bit. For some time he had been putting together scattered fragments of his own autobiography. But lately, as the ceaseless cycle of fever and crisis, relapse and remission continued seemingly without end, he had put aside his notebook and pen. From time to time in recent years he had been approached by authors or would-be authors who had put themselves forward as his prospective biographer. Many of these had been wishful-thinkers and no-hopers, but one or two had been serious candidates. So long as he was well and active the story of his life was his own copy, and his alone. But now the situation had changed. He asked his wife Lee to read the book aloud to him, and as she read he began to feel that perhaps he had found his biographer. Henceforth the biography was a reality, something to aim at, a goal to achieve. In the highly adverse circumstances in which he found himself, it was to be one of the last preoccupations of his life.

Gerald was anxious to meet up with me in order to talk about the project face to face, and to come to a decision. But each time Lee called me with a date on which to visit the hospital she would have to ring back to reschedule, because Gerald was back in intensive care. Our meeting was not to be. Shortly after his death in January 1995, Lee authorised me to write a full and frank account of his life and work.

Over the next two years, I came to know more about Gerald Durrell than I did about myself. I thought I had got the measure of the man. Then one day I came upon an extraordinary, and utterly unexpected, sequence of private love letters. Here was a man moved by passion, joy, fear, romantic and erotic love, and by gratitude to the love of his life and to life itself and to the world. As I read, I inwardly sang and laughed and declaimed with him. And then I came to a letter written on 31 July 1978, and I fell silent:

I have seen a thousand moons: harvest moons like golden coins, winter moons as white as ice chips, new moons like baby swans’ feathers … I have felt winds as tender and warm as a lover’s breath, winds straight from the South Pole, bleak and wailing like a lost child … I have known silence: the implacable stony silence of a deep cave; the silence when great music ends … I have heard tree frogs in an orchestration as complicated as Bach singing in a forest lit by a million emerald fireflies. I have heard the cobweb squeak of the bat, wolves baying at a winter’s moon … I have seen hummingbirds flashing like opals round a tree of scarlet blooms. I have seen whales, black as tar, cushioned on a cornflower blue sea. I have lain in water warm as milk, soft as silk, while around me played a host of dolphins … All this I did without you. This was my loss …

As I read, I began to realise, first with disbelief and then with some degree of unease, that the voice inside my head was no longer my own. I had heard enough of Gerald Durrell’s soft, beguiling, cultured English diction on tapes of interviews and radio and television broadcasts to be able to identify it with certainty. There was no doubt. The voice reading this impassioned love letter was Durrell’s own. Not only had I got the measure of Gerald Durrell; Gerald Durrell, it seemed, had got the measure of me. I recalled something Sir David Attenborough had said at the farewell celebration of the man in London after his death: ‘Gerald Durrell was magic.’

This, then, is the biography of Gerald Durrell – naturalist, traveller, raconteur, humorist, visionary, broadcaster, best-selling author, one of the great nature writers of the twentieth century, one of the great conservation leaders of the modern world, champion of the animal kingdom, founder and Honourary Director of Jersey Zoo and the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust, saviour of endangered species, champion of the lowly, the defenceless and the doomed.

I don’t think it is hyperbole to say that though Gerald Durrell was not a particularly saintly man – his warts were several, and sometimes spectacular – he led a saintly life in pursuit of a saintly mission: simply put, to save animal species from extinction at the hands of man. In his way he was a latter-day St Francis, confronting a problem that St Francis could never have conceived in his worst nightmare. Since his struggle with that problem helped to kill him, it could be said that Gerald Durrell laid down his life for the animal kingdom and the world of nature he loved.

From the outset this biography was conceived as a full, searching and rounded portrait of the man, his life and his work. It was Lee Durrell’s wish, when she authorised the book after her husband’s death, that it should be so. In other words, though this book is described as the ‘authorised’ biography, I have had carte blanche in the writing of it, and the portrait of the man and the narrative of the life are mine and mine alone – though none of it could have been put together without the help of many others.

What ‘authorised’ actually means in this case is that I have been allowed exclusive access to the personal and professional archives of Gerald Durrell (which are voluminous) and to the files of the organisation he founded and directed, the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust (now renamed the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust). I also enjoyed unqualified freedom in approaching anybody involved in the Gerald Durrell story, of whom there are many.

I would especially like to thank Dr Lee Durrell, Gerald Durrell’s widow and Honorary Director of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, for her unstinting support and tireless assistance during the researching and writing of this biography. I am doubly grateful to her, first for allowing me unconditional access both to the Durrell private archives and the archives of Jersey Zoo and Trust, and second for allowing me to refer to and quote from the unpublished works of Gerald Durrell in this book. I would also particularly like to thank Jacquie Durrell, who plays a crucial part in this story at several key stages, for her tremendous help and encouragement in the preparation of the first half of this biography, as well as those who have contributed to this story from its very centre – Margaret Duncan (née Durrell), Jeremy Mallinson OBE (Director of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust), John Hartley (International Programme Director of the Trust), Simon Hicks (currently Development Director of the Trust) and Tony Allchurch (General Administrator, Jersey Zoo). I am also grateful to Peter Harrison, who between teaching assignments in Poland, Russia and the Gulf delved tirelessly into the Durrells’ early years, introduced me to Gerald Durrell’s Corfu and its dramatis personae, and produced a meticulous gloss on my first draft; John and Vivien Burton of the World Land Trust, for many valuable comments and insights; Anthony Smith, for his untiring advice in matters of science and zoology; and Sir David Attenborough, for critically important guidance. Thanks also to my publisher Richard Johnson and my editor Robert Lacey at HarperCollins for the care and support they have afforded this project, and my agent Andrew Hewson at John Johnson and Gerald Durrell’s agent Anthea Morton-Saner at Curtis Brown for all their hands-on help and encouragement in bringing this huge task to fruition.

My thanks to Curtis Brown, acting on behalf of Mrs Lee Durrell, for permission to quote from published and unpublished works by Gerald Durrell.

Extracts from Lawrence Durrell’s book Prospero’s Cell (Faber & Faber, 1945), Bitter Lemons (Faber & Faber, 1957) and Spirit of Place, Mediterranean Writings (Faber & Faber, 1969) are reproduced by kind permission of the publishers.

Extracts from Jacquie Durrell’s Beasts in my Bed (Collins, 1967) are reproduced by kind permission of the author; extracts from David Hughes’s Himself and Other Animals: A Portrait of Gerald Durrell (Hutchinson, 1997) are reproduced by permission of the author and the publishers.

I would also like to thank Jill Adams; Michael Armstrong; Marie Aspioti; Michael Barrett; Quentin Bloxam (General Curator, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust); Kate and Anna Botting; Gordon Bowker; Gerry Breeze; Nicholas Breeze; Sarah Breeze; Tracy Breeze; Felicity Bryan; Rev. Geoffrey Carr; David Cobham; Philip Coffey; Anthony Condos; Menelaus Condos; Fleur Cowles; Sophie Danforth; Anthony Daniells; Eve Durrell; Mr and Mrs Alex Emmett; Doreen Evans; Dr Roger Evans (Manuscript Department, British Library); Tom Evans; W. Paterson Ferns; Bronwen Garth-Thornton; Bob Golding; Anna Grapes; Peter Grose; Lady Rhona Guthrie; Dr Jeremy Guyer; Jonathan Harris; Paula Harris; Gwen Hayball; E.C. (Teddy) Hodgkin; Penelope Hope (née Durrell); David Hughes; Dr Michael Hunter; The Earl of Jersey; Carl Jones; Colin Jones; Dorothy Keep; Sarah Kennedy; Françhise Kestsman; Patrick Leigh-Fermor; Vi Lort-Phillips; Thomas Lovejoy; Judy Mackrell; Odette Mallinson; Stephen Manessi; Dr Bob Martin; Alexandra Mayhew; Alexia Mercouri; Dr Desmond Morris; Lesley Norton; Richard Odgers; Dr Alan Ogden; Dr Guy O’Keeffe; Peter Olney; Eli Palatiano; Christopher Parsons OBE; Joss Pearson; Peggy Peel; Lucy Pendar; Julian Pettifer; Joan Porter; Tim R. Newell Price (Archivist, Leighton Park School); Betty Renouf; Dr Marielle Risse; Robin Rumboll; Tom Salmon; Peter Scott; Richard Scott-Simon; Dr Bula Senapati; Maree Shillingford; Trudy Smith; Mary Stephanides; Dr Ian Swingland; Dr Christopher Tibbs; Lesley Walden; Sam and Catha Weller; Edward Whitley; Celia Yeo.

Douglas Batting

14 December 1998