Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

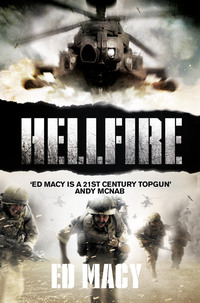

Kitabı oku: «Hellfire», sayfa 2

AIR ATTACK, AIR ATTACK

OCTOBER 1989

Aldershot, England

The echo of voices…

The whisper of tyres on wet tarmac…

A burst of blinding sunlight…

The Royal Artillery (RA) instructor stood with his hands on his hips. A hint of a smile suggested he knew something we didn’t. ‘To be an effective anti-aircraft gunner, you have to be a very good judge of speed and distance.’ He paced up and down in front of us like he was Captain Mainwaring. ‘You cannot afford to waste shots. If you miss first time and adjust quickly, you may, if you’re lucky, get a second chance, but only if the pilot’s below par. If he’s not, if he can fly half decently, like some of the Argies in the Falklands, he’ll manoeuvre unpredictably and then it’s spray-and-pray time. Spray, because that guy’s jinking all over the sky and you’ll never hit him in a month of fucking Sundays; pray, because by now he’s seen your tracer and he knows where you and your little pop-gun are hiding.’

He tapped one of the four pintle-mounted general purpose machine guns (GPMGs). ‘Now which of you sad, sorry bastards is first up?’ He rubbed his hands and blew on them.

I pulled myself to my feet and squinted against the cloudless sky. Behind me, my 2 Para mates gave me some low grunts of encouragement. Behind them, I swore I could hear the sniggers of the RA captain’s support team, but I didn’t let that put me off. I expected nothing less. In the eyes of a young Para the British Army was divided between those wearing the coveted red beret and the rest-the crap-hats.

I’d been given a fifty-round belt of 7.62 and told to fire twenty-to twenty-five-round bursts at the bright red remote-controlled drone that would appear over the frost-bitten ridgeline any second now. Two posts set ten feet away at eleven and one o’clock determined my arc of fire. Outside them, my rounds would land in the nearby village. As a Para marksman, regimental honour weighed heavily on my shoulders, but how difficult could it be? The propellerpowered drone had a wingspan of a metre and a half; at this range it would be the size of a barn door.

The drone would be flying right to left, straight and level. Bang, bang; I’d collect my prize and we could all go home.

I heard a sound like a buzz-saw and pulled the butt of the GPMG hard into my shoulder. There. A bright red cross, its bulbous engine glinting in the sunlight, a hundred feet or so off the deck.

‘Air Attack, Air Attack,’ Mainwaring screamed at the top of his voice.

I placed the drone squarely in the centre of the sights.

Three, two, one…It passed the right-hand post and I gave it a sustained burst. The drone beetled on and disappeared over the ridgeline. I couldn’t believe it. There was a chorus of wolf-whistles from the crap-hats as I breathed in the smell of burnt gun oil. I flushed with embarrassment.

Captain Mainwaring was in my face quick as a wink. ‘Not so easy is it, son? Trouble is, you can’t actually see where your rounds are going, can you? So this time, we’re going to help you.’

A RA bombardier gave me a fresh belt of ammo.

‘We’re loading you up with 1BIT; now you’ll be able to see where your rounds are going.’

(1BIT: one standard 7.62 mm ball round for every one tracer round (1Ball1Tracer = 1BIT).)

I’d be able to adjust my aim and walk the bullets onto the target.

The drone appeared again, nice and steady. With the belt of ammo draped over my left forearm I tracked it and pulled the trigger, spitting out red streaks the very moment it crossed the right-hand post.

Every single glowing round passed behind the stupid fucking thing by yards. I was so stunned I was unable to get in a second burst. The drone wobbled off and the catcalls intensified; some of them this time from my mates.

Mainwaring told me where I was going wrong. I needed to ‘lead’ the aircraft-at this distance, I had to aim a second in front of it and let it fly into the bullets. I should have known about this from the Saturday afternoon war movies I used to watch with my granddad; the ones where the Spitfire pilots talked about ‘deflection shots’-firing at an angle ahead of a crossing enemy aircraft, taking its speed and distance into account.

Round three. This time, my lead was perfect, but for some reason all my bullets disappeared below the drone.

Next time, Mainwaring said, be aware of distance, then fire. Cheeky bastards had flown it further away than last time, catching me out. My lead had been good, but because of ‘ballistic drop’, the bullets had fallen well below the target. I’d show him this time!

Round four. My bullets passed behind it again. The drone-operator had increased its speed. Watch your range, Mainwaring told me, but don’t forget the speed of your target.

Round five. It came screaming in from the left, jinking up and down as well as accelerating and decelerating. The dodgy bastards were taking the piss. I wasn’t even close.

The laughter behind me grew to a cacophony.

‘Am I right in thinking, Para-boy, that you’re an SAS wannabe?’

I said nothing. I didn’t like the way this was going.

‘Didn’t I warn you,’ Mainwaring shrieked, ‘that if you miss, the enemy aircraft will see your tracer and your position will be compromised? Stand by for incoming—’

I began to run.

I ran as fast as I could, legs pounding the rock-hard earth, arms swinging, as I made for the nearest cover, a concrete pillbox around 200 metres away. Over the whistles and catcalls behind me I heard the buzz-saw signature of the drone. The louder it got, the faster I ran. Cary Grant running for his life in North by North-west had nothing on me…

The drone swept in behind me, drowning out the laughter.

I was still thirty metres from the pillbox when it slammed into the small of my back. I hit the ground and the lights went out. I thought I’d been split in two.

I tried to open my eyes, but couldn’t. I heard people talking, but they made no sense. Where were Mainwaring and my mates? Where was I?

‘You okay, mate?’ a bloke said.

‘I think he’s dead…’ A woman’s voice.

‘He fell off his bike in front of that man’s car. He was in the air, upside down, when the car hit him.’

I wanted to tell them that wasn’t what had happened at all. I wanted to tell them I’d been on Salisbury Plain in a live firing exercise against a target drone when the bloody thing decided to go rogue and everything turned to ratshit.

Fuck! The pain…

Someone was trying to move me. I felt like I was being pulled, pushed and prodded. Every time they touched me I wanted to open my mouth and scream, but I couldn’t even whimper.

‘I thought it had taken his head off. It hit him in the back and he was upside down, mate. His head went under the bumper and his feet went through the windscreen. His back must be broken.’

If my back’s broken, why the fuck are you trying to move me? If my back’s broken, how am I going to do SAS Selection?

They’ll pay for this, I thought. A drone goes rogue, hits me in the back and kills all my dreams. My God, I’ll have them…

‘Get the boards. Quick.’ Another woman. Stern, authoritarian.

‘I tell you, he flew off the bonnet and then the guy drove over him…’

‘Drove over his head,’ the first woman said.

‘No, it drove over his shoulder…’

Whatever, I thought. The pain that had threatened to overwhelm me was replaced by a feeling of immeasurable tiredness. I felt myself sliding and falling.

‘Sir, wake up. Can you open your eyes for me?’

I opened my eyes and my confusion deepened as I slowly saw a black woman backlit by a bright orange halo. I thought for a moment that Diana Ross had come to take me away…

‘Can you feel my hand?’

I couldn’t, but all was not lost: I felt something on my face-the rain I could see sparkling in the glow of the street lamp.

‘Can you feel me touching your fingers?’

I was aware of having hands and feet, but I couldn’t feel her touching them.

‘Can you grip my fingers?’

I couldn’t. I couldn’t move a muscle. I tried to shift my head, but it wouldn’t respond. Nothing responded. I couldn’t even speak. I was totally fucked.

The woman unzipped my Barbour jacket. ‘Sweet Jesus, he’s wearing a bin-bag under his coat.’ At best she must be thinking I’m mad and at worst a weirdo pervert.

Leave me alone, I wanted to tell her, because all I want to do is sleep.

Suddenly and with no warning I felt like I was being hit on the back of the head with a road worker’s mallet every time my heart beat.

‘Yeah, he arrested,’ a paramedic yelled. ‘He’s military. Suspected spinal and internal injuries…’

I couldn’t open my eyes but at least the pain was telling me I wasn’t dead.

I wanted to go to sleep again, but a voice in the back of my head told me I needed to stay awake.

And someone seemed to be shoving the end of a broom shank deep into me, just below my rib cage, next to my spine. Every time the ambulance hit the tiniest bump it felt like it was going to burst through my chest. I was John Hurt in my own nightmare version of Alien.

We hit a pothole and I suddenly found my voice. I screamed-full throat, full belly. It filled the ambulance and blotted out the sound of the siren.

‘Fuck me!’ the paramedic said.

I passed out again.

‘Corporal Macy, can you hear me?’

Of course I can hear you; just give me some bloody morphine…

Then: closed abdominal injury, mate, the voice at the back of my head said. Fat chance of the love-drug.

The pain had got worse.

If I couldn’t put up with this, how would I ever be able to pass Selection? Fuck Selection, I’m tired…

‘Corporal Macy, can you hear me?’

I opened my eyes a crack and found myself blinking against bright, brilliant white. No wonder people said they saw angels in places like this. They were delusional; just like I was now.

A guy in a green smock leaned over and shone something into my eyes. ‘You’ve been in an accident, mate.’

Now there’s a surprise.

My head and back were on fire. I tried to move my feet and legs, but couldn’t. With a supreme effort, I managed to raise my head and shoot a glance down my body.

I was on a bed wearing a green gown, in an operating theatre with a lamp suspended over me. It was pushed up and switched off. Maybe they’d already given up on me…

A six-inch square rubber block was strapped tightly to my belly. The strap had some kind of winch attached to it. It was fucking killing me.

At least I now knew why I was paralysed. My wrists and ankles were cuffed to the bed with more straps.

‘Can you tell me where the pain is?’ the guy in green asked.

‘Everywhere,’ I said. ‘Please, morphine…’

Someone else approached the bed, a stethoscope around his neck. They looked at each other, then at me. ‘Not yet,’ he said. ‘Can you tell us where it hurts most?’

He injected my right arm with a clear liquid from a big syringe. Whatever it was, it wasn’t pain relief.

I screamed.

‘My back is killing me.’

‘Where specifically?’

‘The small of my back. Please. You’ve got to give me something for the pain. I’m begging you—’

He cranked the handle several notches. The clicks were like machine-gun fire. I screamed again.

‘I’m sorry, Corporal Macy, really I am.’

Like fuck, I thought, as another wave of pain crashed through me.

The lights went out again.

My torso sprang upwards as soon as they took the tension off the strap. They lifted me onto another bed and finally relieved some of the pain.

They’d had to pump X-ray dye into my arm to identify the source of my internal bleeding. Then they’d squeezed the blood out of my kidneys. When they released the pressure, the blood had seeped back into them, the rupture clotted and my life had been saved.

‘Think of your internal organs as being connected together by pipes.’ The junior doctor’s bloodshot blue eyes were set in a broad, unsmiling face. ‘When you get hit as hard as you did, all your organs get thrown around and the pipes connecting them detach. Then you bleed internally and the bleeding can’t be stemmed. You die from a loss of circulating body fluid. We think you were hit at about 50 mph, a lot faster than is considered survivable. Fortunately, your stomach muscles are so strong and your body so fit that the impact did not rearrange your internal organs as it would have for most people, so all your pipes remained miraculously connected. The force of the collision did, however, rupture your kidneys and damage a number of other organs. Your heart arrested as it fought to keep you alive. You arrested twice, in fact.’

He smiled. ‘You’re a very lucky man. The surgeon couldn’t operate and didn’t give you more than a 20 per cent chance of pulling through. Thank God you’ve been keeping yourself fit, Corporal Macy. By rights you should be dead.’

Funny what you dream about when you’re on the point of checking out. Being pursued by a drone across a military firing range must have been on my mind because we’d recently done antiaircraft drills at Larkhill.

‘What hit me?’

‘You don’t remember?’

I’d have shaken my head if I wasn’t in so much pain.

He told me that a number of witnesses had come forward. I’d been cycling along Queen’s Avenue, close to the barracks. It was dark and it had been raining.

Slowly, it came back to me. I remembered the orange glow of the street lamps and their reflection in the puddles as I’d held my bike’s front wheel between the yellow lines at the edge of the road. I’d followed the same routine for several weeks: two hours in low gear at full pelt with a bin-bag under my clothes to raise my temperature and make me sweat. After that, I’d get off the bike and go for a long run.

I’d been getting myself fit for SAS Selection.

Something had hit my right handlebar; I remembered the bang. I’d looked up and seen a Volvo. It had overtaken too close and clipped me with its wing mirror. I’d struggled for balance and my wheel had clipped the kerb and I’d careered into the oncoming lane.

I remembered headlights very bright in my face, the world turning upside down and then something colliding with me…

The rest was filled in by the policeman who came to take my RTA victim’s statement.

When the front wheel of my bike locked at ninety degrees I’d gone over the handlebars and been hit by a car going too fast in the opposite direction. I was totally inverted when it ploughed into me, its radiator grille striking me in the small of the back. My head went under the bumper and my feet went through the windscreen. The driver had slammed on the brakes but not quickly enough to prevent him ploughing over my shoulder. No wonder I was a complete fucking mess.

I finally summoned the courage to ask the doctors the only question that mattered. SAS Selection. What were my chances?

A big fat zero, as it turned out. They told me I’d been lucky not to be invalided out of the Paras. The good news was that they were discharging me from hospital; I was heading home-if you could call army accommodation on the edge of Aldershot ‘home’.

Over the next few months, my mates came in to bathe me because I was in too much pain to move. I had a livid purple bruise from the toes on my right foot-where it had gone through the windscreen-all the way up my leg, across my arse, my back and my shoulder, finally petering out somewhere under my hairline.

After several weeks, I started to walk again with the use of a putter and a pitching wedge. As far as 2 Para was concerned, this wasn’t a military injury; in the old days it was a case of ‘get on with it and let us know when you’re capable of fighting again’.

I was in too much pain to even think about that.

Months later when I was sent back to hospital for another checkup, they spotted my other injuries; the ones they should have discovered before they discharged me.

I’d suffered multiple fractures all over my body and some had healed in the wrong positions.

Like the guy said, my fighting days were over.

ARRESTED AND TESTED

I’d joined the Paras in 1984 and thought I’d found my niche in life. Being accepted by this elite regiment had been my sliding-doors moment. The accident had slammed the doors firmly back in my face.

I was born and raised in the north-east, but, as a kid, constantly found myself in trouble. My parents split up when I was very young. Against my will I remained with my mother as did my younger brother. He was even more out of control than me and ended up in a secure institution; a boarding school for the ‘socially challenged’ they called it back then. One day he was with us, the next he was gone. He was the closest thing I had-the only real constant in my life-and I was angry that ‘they’, whoever they were, had taken him from me.

I didn’t know at the time that my mother couldn’t cope. Looking back, though, I wasn’t surprised. We were like the Bash Street Kids on crack, my brother and I; trouble through and through.

When I wasn’t skipping school, I was fighting the playground bullies and generally causing mayhem. It was only by a complete fluke that I managed to avoid a correctional institution. I had good reason to be grateful. However hard I thought I was, I’d seen the movie Scum, starring a young Ray Winstone, and didn’t like the look of it one little bit. A Residential School for Boys, Special School, Borstal or whatever you want to call these places-it would have killed me. It’s a miracle it didn’t kill my brother.

As soon as I could leave school, I did, and without a qualification to my name.

Finally back in the company of my father, I took a job as an engineering apprentice at a small workshop ten miles from home. The high point of my apprenticeship was turning, milling and drilling the portholes for Britain’s first iron-hulled warship. HMS Warrior was under restoration in Hartlepool dockyard and I had an important job to do. It was the early eighties, unemployment was going through the roof, and I thought I’d live and die in the north-east.

A thousand fox doorknockers and sixty-seven poorly paid portholes later, my work on Warrior was done-and so was I, until I met Stig down the pub one day. A local hard man, he was home on leave from the Paras. Two things impressed me about Stig. He had money-more money than I thought possible-and he could tell a story. Most of his stories concerned the Falklands, where the Paras had just been in the thick of it. If I could join the Parachute Regiment, I reasoned, I’d not only have money, but would end up seeing the world-even better, fighting in far-flung parts of it.

Stig laughed when I told him this, but when he saw I was serious he told me I’d have to train and train hard. So I pounded the beach every day before and after work; come rain, wind or snow, it didn’t matter. Gradually, I built up my fitness. When it became easy, I tied a rope to a tractor tyre, fixed it round my waist and ran up and down the beach dragging the tyre behind me. People thought I was mad, but in August 1984 it got me where I wanted.

I was a fully fledged member of 2 Para by April of the following year, but as time passed, even that wasn’t enough: I set my sights on joining the SAS. Being in the Paras was no guarantee of passing Selection. The SAS needed specialists, so I concentrated with every fibre of my being on becoming the battalion’s best signaller, then on coming top of the combat medics’ course. Nothing was going to stop me achieving my goal. Or so I thought.

On a cold, rainy October night in Aldershot, the Paras’ garrison town in Hampshire, some twat in a Volvo clipped my bike and sent me over the handlebars. Flying through the air, upside down and facing backwards, I was hit by a car driving too fast in the opposite direction.

With their unorthodox methods, the surgeons saved me from death by internal bleeding. Too bad the hospital didn’t also check if I’d broken any bones before it discharged me. By the time I’d got a second opinion, my right foot, both ankles and right hip had set in the wrong positions. They were completely fucked, as were my back, knees and right shoulder. Not only was I out of contention for the SAS, I was medically unfit for duty in any front line regiment.

To compound matters, the hospital had ‘lost’ my medical records. Closing ranks, they’d removed all the evidence. It was like my case never existed.

As far as the lads alongside me saw it it didn’t make much difference: my soldiering was over. But I refused to accept a desk job and the quest was on to find a way back into combat without a Bergen.

A mate of mine suggested I should apply for the Army Air Corps (AAC). ‘You want to be in the thick of it?’ he said. ‘You could end up flying for the SAS.’

He showed me a book. Inside was a photo of a pilot in an army helicopter, his eyes blacked out with censor-ink. Behind him were four fully tooled-up members of the Special Air Service. He was right. If I couldn’t fight for the SAS, maybe I could fly for them. How cool would that be? I could get back to the front line without getting off my arse.

All I had to do now, I figured, was to con my way past the medicals that awaited anyone who wanted to become a pilot. Fate had already stepped in and given me a hand. Because I had no recent medical records, there was no paperwork to attest to the fact that little over a year ago I’d been mangled in a life-threatening accident.

Although 2 Para weren’t keen on anyone leaving eventually my application was processed. I passed the aptitude tests and managed to bluff my way through the medicals.

Switching from the Paras to train as a pilot-provided I was accepted-meant I’d be stuck as a corporal for another four years, but I wasn’t rank hungry. I was on a mission.

Within weeks I was told I’d been accepted for ‘grading’ at Middle Wallop, the AAC’s main airfield a stone’s throw from Salisbury Plain.

Grading was a process for assessing a potential pilot’s ability to listen, absorb and replicate simple flying manoeuvres. It was a baseline test that included ground school and was designed to see if we had the ability to cope with the army pilots’ course.

I was to start in July 1991.

I didn’t know if I could fly or not, but by hook or by crook I would give it everything I had.

I was waiting outside the clothing store for my flying suit when a giant of a man nudged me out of the way with a dismissive, semi-hostile look and threw a pair of tatty old gloves onto the counter. The civvie behind the counter half-jumped to attention, threw the man-mountain a sickly smile and laid out a nice new pair of pristine white chamois-leather gloves in front of him.

‘There you go, Mr Palmer. Your size if I’m not mistaken.’ They must have skinned a whole mountain antelope to make just one pair for him.

Mr Palmer never said a word. He flicked a glance at my maroon beret, leaned into my personal space and stared into my eyes. I figured he either had something against the way I wore my silver-winged cap badge-2 Para style-round by my left ear, or he just didn’t like Paras, full stop.

He gave me a thin smile, tucked his gloves into his pocket and walked out.

I filed Mr Palmer’s name away. I had other things to worry about right then. The trouble with grading was the fact that none of the instructors-crusty old pilots who had been in the RAF, but were now civvies, well beyond retirement age-gave you any feedback on your chances of success. I had no idea how I was doing.

Captain Tucker called us together in the Chipmunk hangar briefing room. A tall, softly spoken, well-to-do Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers officer, he was a candidate just like us, but because of his rank he was the grading course leader. We were told we needed an average score of fifty for each exercise. There would be twelve exercises altogether, with a final handling assessment tacked on the end.

When they debriefed us, the instructors wrote everything down in blue A4 ring binders that had our names on the spines.

I desperately wanted to know what was in my binder.

Standing outside the hangar with the smokers one day, I could see through the window into the room where the instructors kept them. The folders were in a neat row on the second shelf of a steel cabinet. As I glanced nonchalantly past the smokers, in came Chopper Jennings, one of the instructors, and locked the cabinet. Then he opened the top-right drawer of the desk, lifted out a big orange folder and flung in the key. Jennings took the key to the drawer away with him, but that didn’t bother me. I could pick a drawer lock, no problem. Doors didn’t present an obstacle either.

I asked one of the ground crew what time the hangar opened the following morning. I told him I wanted to practise my checks in peace. Six, he told me, and from that moment my mind was set.

I told my Para mate Chris my plan but he wasn’t getting up early. He didn’t want me to tell him if he was failing; only to let him know if he was passing.

Suit yourself, I told him.

The next morning, I hung around for the ground crew to open the hangar and push out the ‘Chippies’-our De Havilland Chipmunk T10 training aircraft-into the crisp summer morning light. I crept past them, made my way to the corridor and reached the door to the office. Skills I’d learned from my mates at school for cracking locks and flipping Yales came in very handy. The key for the steel cabinet was where Chopper Jennings had put it. I opened the cabinet and selected the folder with ‘MACY’ on the spine.

I was scoring 54s and 55s. Each piece of airmanship was carefully marked. I studied the details closely. Mr Fulford, my sweet old instructor, had marked me down for not looking out enough. This, he said, could lead to a mid-air collision, and would need to be rectified if I was to become a pilot.

No sooner said than done, Mr Fulford.

I looked at my mate’s folder and he was bombing big-style. Then I looked at some of the other guys to see how they were doing. Only a few were doing okay, the majority were borderline and some were totally losing it.

When I got back, Chris asked how he was getting on and I told him I hadn’t been able to get into the office, but would try again. What else could I say?

The following day, bombing along in my Chippie with Mr Fulford behind me, I made sure that my head never stopped moving as I scanned the Hampshire skies for other aircraft.

When I broke into the office and sneaked a look at my file the following day, I was gratified to see that my situational awareness had improved greatly, but I needed to work on my navigational accuracy.

Your wish, Mr Fulford, is my command.

My eighth sortie was to perform a loop. I went for it, big-time. Approaching the top of the loop the blood drained from my thick skull and my vision became impaired by dark grey spots. By the time I had the red and white bird completely inverted, the spots had grown and merged and I was totally blind.

From the tone of his voice I could tell that it had caught nice Mr Fulford out too.

‘Are…your…wings…level…?’ he gasped.

I didn’t have a clue; I was fighting a losing battle to stay conscious.

I grunted my reply.

I woke to hear the Gypsy Major engine screaming, quickly pulled out of the dive and levelled back off at the altitude I had started my first aerobatic manoeuvre. That’s it, I thought. I must have failed now. But the following morning I’d somehow got away with it.

By the ninth sortie, I’d accumulated enough points to chill out a bit. I stopped sneaking into the office after my tenth flight, knowing I was almost home and dry.

Along the way, I had also learned why they’d given Jennings his nickname. He wasn’t some helicopter ace after all; in fact, he’d never flown choppers. He just marked us so harshly that he chopped more people off the grading course than any other instructor. It was all I needed to justify my early morning sorties. You had to fight fire with fire.

On the day we were due to leave, two weeks and thirteen flying hours after the grading course started, we were lined up outside the Flying Wing Chief Instructor’s office in rank order.

Decision time. I knew pretty much who had passed and who had failed, but there were still a few borderline cases I wasn’t so sure about.

As a corporal I was way down the line, just behind my pal Chris.

A lieutenant was called into the office. I held my breath, knowing he was about to have the carpet pulled from under him. He emerged a moment or two later, punching the air. ‘I’ve passed. I’m a training risk, but I’ve passed.’

I knew that from the files. How on earth did he scrape a pass?

A sergeant came out looking devastated. But from my peeks at his file I knew he was better than the lieutenant.

What the fuck was going on here? My heart sank; it seemed little better than a lottery.

I began to panic. What if I’d blown it in the last few sorties? Had I taken my eye off the ball? That was it, I convinced myself; the lieutenant must have greatly improved in the final few days and the sergeant had let down his guard.

Jesus. How had I done?

Chris slunk in and reappeared with the inevitable news. His grades were awful.

Then it was my turn, the moment of truth. The Flying Wing Chief Instructor, the Chippie Chief Instructor and a high-ranking, big cheese AAC officer were all ranged behind a table in front of me. I came to a halt and saluted. I could see my heart pounding through my shirt. This was it. This was my one shot.

‘Corporal Macy, how do you think you have done?’ the Big Cheese asked.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.