Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

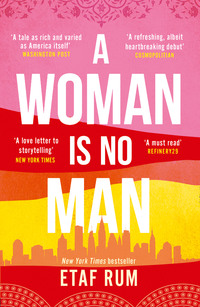

Kitabı oku: «A Woman is No Man», sayfa 2

Isra slapped him.

Shocked, she waited for him to apologize, to muster up something about how he hadn’t meant to kiss her, how his body acted of its own accord. But he only looked away, face flushed, and buried his eyes between the graves.

With great effort, she forced herself to look at the cemeteries. She thought perhaps there was something between the graves she could not see, some secret to make sense of what was happening. She thought about A Thousand and One Nights, how Princess Shera had wanted to become human so she could marry Sindbad. Isra didn’t understand. Why would anyone want to be a woman when she could be a bird?

“He tried to kiss me,” Isra told Mama after Adam and his family left, whispering so Yacob wouldn’t hear.

“What do you mean, he tried to kiss you?”

“He tried to kiss me, and I slapped him! I’m sorry, Mama. Everything happened so fast, and I didn’t know what else to do.” Isra’s hands were shaking, and she placed them between her thighs.

“Good,” Mama said after a long pause. “Make sure you don’t let him touch you until after the wedding ceremony. We don’t want this American family to go around saying we raised a sharmouta. That’s what men do, you know. Always put the blame on the woman.” Mama stuck out the tip of her pinkie. “Don’t even give him a finger.”

“No. Of course not!”

“Reputation is everything. Make sure he doesn’t touch you again.”

“Don’t worry, Mama. I won’t.”

The next day, Adam and Isra took a bus to Jerusalem, to a place called the US Consulate General, where people applied for immigrant visas. Isra was nervous about being alone with Adam again, but there was nothing she could do. Yacob couldn’t join them because his Palestinian hawiya, issued by the Israeli military authorities, prevented him from traveling to Jerusalem with ease. Isra had a hawiya too, but now that she was married to an American citizen, she would have less difficulty crossing the checkpoints.

The checkpoints were the reason Isra had never been to Jerusalem, which, along with most Palestinian cities, was under Israeli control and couldn’t be entered without a permit. The permits were required at each of the hundreds of checkpoints and roadblocks Israel had constructed on Palestinian land, restricting travel between, and sometimes within, their own cities and towns. Some checkpoints were manned by heavily armed Israeli soldiers and guarded with tanks; others were made up of gates, which were locked when soldiers were not on duty. Adam cursed every time they stopped at one of these roadblocks, irritated at the tight controls and heavy traffic. At each one he waved his American passport at the Israeli soldiers, speaking to them in English. Isra could understand a little from having studied English in school, and she was impressed at how well he spoke the language.

When they finally arrived at the consulate, they waited in line for hours. Isra stood behind Adam, head bowed, only speaking when spoken to. But Adam barely said a word, and Isra wondered if he was angry at her for slapping him on the balcony. She contemplated apologizing, but secretly she thought she had nothing to apologize for. Even though they had signed the Islamic marriage contract, he had no right to kiss her like that, not until the night of the wedding ceremony. Yet the word sorry brewed on her tongue. She forced herself to swallow it down.

At the main window, they were told it would take only ten days for Isra to receive her visa. Now Yacob could plan the wedding, she thought as they strolled around Jerusalem afterward. Walking the narrow roads of the old city, Isra was overwhelmed by sensations. She smelled chamomile, sage, mint, and lentils from the open burlap sacks lined up in front of a spice shop, and the sweet aroma of freshly baked knafa from a nearby dukan. She spotted wire cages holding chickens and rabbits in front of a butcher shop, and several boutiques displaying myriads of gold-plated jewelry. Old men in hattas sold colorful scarves on street corners. Women in full black attire hurried through the streets. Some wore embroidered hijabs, tight-fitted pants, and round sunglasses. Others wore no hijab at all, and Isra knew they were Israeli. Their heels click-clacked on the uneven sidewalk. Boys whistled. Cars weaved through the narrow roads, honking, leaving a trail of diesel fumes behind. Israeli soldiers monitored the streets, long rifles slung across their slender bodies. The air was filled with dirt and noise.

For lunch, Adam ordered falafel sandwiches from a food cart near Al-Aqsa Mosque. Isra stared at the gold-topped dome in awe as they ate.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” Adam said between mouthfuls.

“It is,” Isra said. “I’ve never seen it before.”

Adam turned to face her. “Really?”

She nodded.

“Why not?”

“It’s hard getting here.”

“I’ve been gone for so long, I’d forgotten what it was like. We must’ve been stopped by half a dozen roadblocks. It’s absurd!”

“When did you leave Palestine?”

Adam chewed on his food. “We moved to New York in 1976, when I was sixteen. My parents have visited a couple of times since, but I’ve had to stay behind and take care of my father’s deli.”

“Have you ever been inside the mosque?”

“Of course. Many, many times. I wanted to be an imam growing up, you know. A priest. I spent Ramadan sleeping here one summer. I memorized the entire Qur’an.”

“Really?”

“Yeah.”

“So is that what you do in America? You’re a priest?”

“Oh, no.”

“Then what do you do?”

“I own a deli.”

“But why aren’t you an imam?” Isra asked, emboldened by their first conversation.

“I couldn’t do that in America.”

“What do you mean?”

“My father needed me to help him run the family business. I had to give that up.”

“Oh.” Isra paused. “I didn’t expect that.”

“Why not?”

“I just always thought . . .” She stopped, thinking better of it.

“What?”

“I just assumed you’d be free.” He gave her a curious expression. “You know, because you’re a man.”

Adam said nothing, continuing to stare. Finally he said, “I am free,” and looked away.

Isra studied Adam for a long time as they finished their sandwiches. She couldn’t help but think of the way his face had stiffened at the mention of his childhood dream. His tight smile. She pictured him in the mosque during Ramadan, leading the maghrib prayer, reciting the Qur’an in a strong, musical voice. It softened her to picture him working behind a cash register, counting money, and stocking shelves when he wanted to be leading prayer in a mosque. And Isra thought for the first time, sitting there beside him, that perhaps it would not be so hard to love him after all.

Isra spent her last night in Birzeit propped in a gold metal chair, lips painted the color of mulberries, skin draped in layers of white mesh, hair wound up and sprayed with glitter. Around her, the walls spun. She watched them grow bigger and bigger until she was almost invisible, then get smaller and smaller as if they were crushing her. Women in an assortment of colors danced around her. Children huddled in corners eating baklava and drinking Pepsi. Loud music struck the air like fireworks. Everyone was cheering, clapping to the beat of her quivering heart. She nodded and smiled to their congratulations, yet inside she wasn’t sure how long she could stave off tears. She wondered if the guests understood what was happening, if they realized she was only a few hours away from boarding a plane with a man she barely knew and landing in a country whose culture was not her own.

Adam sat beside her, his black suit crisp against his white button-down shirt. He was the only man in the wedding hall. The others had a room of their own, away from the sight of the dancing women. Even Adam’s younger brothers, Omar and Ali, whom Isra had only met minutes before the wedding, were forbidden. She couldn’t tell how old they were, but they must’ve been in their twenties. Every now and then, one would poke his head in to watch the women on the dance floor, and a woman would remind him to stay in the men’s section. Isra scanned the room for her own brothers. They were all too young to sit in the men’s section, and she spotted them running around the far corner of the hall. She wondered if she would ever see them again.

If happiness were measured in sound, Adam’s mother was the happiest person in the room. Fareeda was a large, broad woman, and Isra felt the dance floor shrink in her presence. She wore a red-and-black thobe, with oriental patterns embroidered on the sleeves, and a wide belt of gold coins around her thick waist. Black kohl was smeared around her small eyes. She sang along to every song in a confident voice, twirling a long white stick in the air. Every minute or so, she brought her hand to her mouth and let out a zughreta, a loud, piercing sound. Her only daughter, Sarah, who looked about eleven or so, threw rose petals at the stage. She was a younger, slimmer version of her mother: dark almond eyes, black curls flowing wildly, skin as golden as wheat. Isra could almost see a grown version of Sarah sitting as she sat now, her tiny frame buried beneath a white bridal dress. She winced at the thought.

She looked around for her mother. Mama sat in the corner of the wedding hall, fidgeting with her fingers. So far she had not left her seat throughout the entire wedding, and Isra wondered if she wanted to dance. Perhaps she was too sad to dance, Isra thought. Or perhaps she was afraid to send the wrong message. Growing up, Isra had often heard women criticize the mother of the bride for celebrating too boisterously at the wedding, too excited to be rid of her daughter. She wondered if Mama was secretly excited to be rid of her.

Adam pounded on a darbuka drum. Startled, Isra looked away from Mama. She could see Fareeda handing Adam the white stick and pulling him down to the dance floor. He danced with the stick in one hand and the darbuka in the other. The music was deafening. Women around them clapped, glancing at Isra enviously as if she had won something that was rightfully theirs. She could almost hear them thinking, How did a plain girl like her get so lucky? It should be my daughter going to America.

Then Adam and Isra were dancing together. She didn’t quite know what to do. Even though Mama had always nagged her about dancing at events, saying it was good for her image, that mothers would be more likely to notice her if she was onstage, Isra had never listened. It felt unnatural to dance so freely, to display herself so openly. But Adam seemed perfectly comfortable. He was jumping on one foot, one hand behind his back, the other waving the stick in the air. With the Palestinian flag wrapped around his neck and a red velvet tarboosh on his head, Isra thought he looked like a sultan.

“Use your hands,” he mouthed.

She lifted both arms above her waist, dangling her wrists. She could see Fareeda nodding in approval. A group of women encircled them, moving their hands to the rhythm of the darbuka. They wore patterned red thobes with gold coins attached at their hips. Some held up round, flaming candles. Others placed a lit candlestick over each finger, waving their shimmering hands in the air. One woman even wore a tiered crown made of candles, so that it looked as though her head were on fire. The dance floor glistened like a chandelier.

The music stopped. Adam grabbed Isra by the elbow and led her off the dance floor. Fareeda followed, carrying a white basket. Isra hoped she could return to her seat, but Adam stopped in the center of the stage. “Face the crowd,” he told her.

Fareeda opened the basket to display a wealth of gold jewelry within. There were oohs and aahs from the crowd. She handed Adam one piece of gold at a time, and he secured each item on Isra’s skin. Isra stared at his hands. His fingers were long and thick, and she tried to keep from flinching. Soon heavy necklaces hung from her neck, their thick coins cold against her skin. Bracelets laced her wrists like ropes, their ends shaped like snakes. Coin-shaped earrings pricked her ears; rings covered her fingers. After twenty-seven pieces of gold, Fareeda threw the empty basket in the air and let out another zughreta. The crowd cheered, and Isra stood before them, wrapped in gold, unable to move, a mannequin on display.

She had no idea what life had in store for her and could do nothing to alter this fact. She shivered in horror at the realization. But these feelings were only temporary, Isra reminded herself. Surely she would have more control over her life in the future. Soon she would be in America, the land of the free, where perhaps she could have the love she had always dreamed of, could lead a better life than her mother’s. Isra smiled at the possibility. Perhaps someday, if Allah were to ever grant her daughters, they would lead a better life than hers, too.

Part I

Deya

BROOKLYN

Winter 2008

Deya Ra’ad stood by her bedroom window and pressed her fingers against the glass. It was December, and a dust of snow covered the row of old brick houses and faded lawns, the bare plane trees lining the sidewalk, the cars parallel-parked down Seventy-Second Street. Inside her room, alongside the spines of her books, a crimson kaftan provided the only other color. Her grandmother, Fareeda, had sewn this dress, with heavy gold embroidery around the chest and sleeves, specifically for today’s occasion: there was a marriage suitor in the sala waiting to see Deya. He was the fourth man to propose to her this year. The first had barely spoken English. The second had been divorced. The third had needed a green card. Deya was eighteen, not yet finished with high school, but her grandparents said there was no point prolonging her duty: marriage, children, family.

She walked past the kaftan, slipping on a gray sweater and blue jeans instead. Her three younger sisters wished her luck, and she smiled reassuringly as she left the room and headed upstairs. The first time she’d been proposed to, Deya had begged to keep her sisters with her. “It’s not right for a man to see four sisters at once,” Fareeda had replied. “And it’s the eldest who must marry first.”

“But what if I don’t want to get married?” Deya had asked. “Why does my entire life have to revolve around a man?”

Fareeda had barely looked up from her coffee cup. “Because that’s how you’ll become a mother and have children of your own. Complain all you want, but what will you do with your life without marriage? Without a family?”

“This isn’t Palestine, Teta. We live in America. There are other options for women here.”

“Nonsense.” Fareeda had squinted at the Turkish coffee grounds staining the bottom of her cup. “It doesn’t matter where we live. Preserving our culture is what’s most important. All you need to worry about is finding a good man to provide for you.”

“But there are other ways here, Teta. Besides, I wouldn’t need a man to provide for me if you let me go to college. I could take care of myself.”

At this, Fareeda had lifted her head sharply to glare at her. “Majnoona? Are you crazy? No, no, no.” She shook her head with distaste.

“But I know plenty of girls who get an education first. Why can’t I?”

“College is out of the question. Besides, no one wants to marry a college girl.”

“And why not? Because men only want a fool to boss around?”

Fareeda sighed deeply. “Because that’s how things are. How they’ve always been done. You ask anyone, and they’ll tell you. Marriage is what’s most important for women.”

Every time Deya replayed this conversation in her head, she imagined her life was just another story, with plot and rising tension and conflict, all building to a happy resolution, one she just couldn’t yet see. She did this often. It was much more bearable to pretend her life was fiction than to accept her reality for what it was: limited. In fiction, the possibilities of her life were endless. In fiction, she was in control.

For a long time Deya stared hesitantly into the darkness of the staircase, before climbing, very slowing, up to the first floor, where her grandparents lived. In the kitchen, she brewed an ibrik of chai. She poured the mint tea into five glass cups and arranged them on a silver serving tray. As she walked down the hall, she could hear Fareeda in the sala saying, in Arabic, “She cooks and cleans better than I do!” There was a rush of approving sounds in the air. Her grandmother had said the same thing to the other suitors, only it hadn’t worked. They’d all withdrawn their marriage proposals after meeting Deya. Each time Fareeda had realized that no marriage would follow, that there was no naseeb, no destiny, she had smacked her own face with open palms and wept violently, the sort of dramatic performance she often used to pressure Deya and her sisters to obey her.

Deya carried the serving tray down the hall, avoiding her reflection in the mirrors that lined it. Pale-faced with charcoal eyes and fig-colored lips, a long swoop of dark hair against her shoulders. These days it seemed as though the more she looked at her face, the less of herself she saw reflected back. It hadn’t always been this way. When Fareeda had first spoken to her of marriage as a child, Deya had believed it was an ordinary matter. Just another part of growing up and becoming a woman. She had not yet understood what it meant to become a woman. She hadn’t realized it meant marrying a man she barely knew, nor that marriage was the beginning and end of her life’s purpose. It was only as she grew older that Deya had truly understood her place in her community. She had learned that there was a certain way she had to live, certain rules she had to follow, and that, as a woman, she would never have a legitimate claim over her own life.

She put on a smile and entered the sala. The room was dim, every window covered with thick, red curtains, which Fareeda had woven to match the burgundy sofa set. Her grandparents sat on one sofa, the guests on the other, and Deya set a bowl of sugar on the coffee table between them. Her eyes fell to the ground, to the red Turkish rug her grandparents had owned since they emigrated to America. There was a pattern embossed across the edges: gold coils with no beginnings or ends, all woven together in ceaseless loops. Deya wasn’t sure if the pattern had gotten bigger or if she had gotten smaller. She followed it with her eyes, and her head spun.

The suitor looked up when she neared him, peering at her through the peppermint steam. She served the chai without looking his way, all the while aware of his lingering gaze. His parents and her grandparents stared at her, too. Five sets of eyes digging into her. What did they see? The shadow of a person circling the room? Maybe not even that. Maybe they saw nothing at all, a serving tray floating on its own, drifting from one person to the next until the teakettle was empty.

She thought of her parents. How would they feel if they were here with her now? Would they smile at the thought of her in a white veil? Would they urge her, as her grandparents did, to follow their path? She closed her eyes and searched for them, but she found nothing.

Her grandfather turned to her sharply and cleared his throat. “Why don’t you two go sit in the kitchen?” Khaled said. “That way you can get to know each other.” Beside him, Fareeda eyed Deya anxiously, her face revealing its own message: Smile. Act normal. Don’t scare this man away, too.

Deya recalled the last suitor who had withdrawn his marriage proposal. He had told her grandparents that she was too insolent, too questioning. That she wasn’t Arab enough. But what had her grandparents expected when they came to this country? That their children and grandchildren would be fully Arab, too? That their culture would remain untouched? It wasn’t her fault she wasn’t Arab enough. She had lived her entire life straddled between two cultures. She was neither Arab nor American. She belonged nowhere. She didn’t know who she was.

Deya sighed and met the suitor’s eyes. “Follow me.”

She observed him as they settled across from each other at the kitchen table. He was tall and slightly plump, with a closely shaved beard. His pecan hair was parted to one side and brushed back from his face. Better-looking than the other ones, Deya thought. He opened his mouth as if to speak but proceeded to say nothing. Then, after a few moments of silence, he cleared his throat and said, “I’m Nasser.”

She tucked her fingers between her thighs, tried to act normal. “I’m Deya.”

There was a pause. “I, um . . .” He hesitated. “I’m twenty-four. I work in a convenience store with my father while I finish school. I’m studying to be a doctor.”

She gave a slow, reluctant smile. From the eager look on his face, she could tell he was waiting for her to do as he did, recite a vague representation of herself, sum up her essence in one line. When she didn’t say anything, he spoke again. “So, what do you do?”

It was easy for her to recognize that he was just being nice. They both knew a teenage Arab girl didn’t do anything. Well, except cook, clean, and catch up on the latest Turkish soap operas. Maybe her grandmother would have allowed her and her sisters to do more had they lived back home, in Palestine, surrounded by people like them. But here, in Brooklyn, all Fareeda could do was shelter them at home and pray they remained good. Pure. Arab.

“I don’t do much,” Deya said.

“You must do something. You don’t have any hobbies?”

“I like to read.”

“What do you read?”

“Anything. It doesn’t matter what it is, I’ll read it. Trust me, I have the time.”

“And why is that?” he asked, knotting his brows.

“My grandmother doesn’t let us do much. She doesn’t even like it when I read.”

“Why not?”

“She thinks books are a bad influence.”

“Oh.” He flushed, as though finally understanding. After a moment he asked, “My mother said you go to an all-girls Islamic school. What grade are you in?”

“I’m a senior.”

Another pause. He shifted in his seat. Something about his nervousness eased her, and she let her shoulders relax.

“Do you want to go to college?” Nasser asked.

Deya studied his face. She had never been asked that particular question the way he asked it. Usually it sounded like a threat, as though if she answered yes, a weight would shift in the scale of nature. Like it was the worst possible thing for a girl to want.

“I do,” she said. “I like school.”

He smiled. “I’m jealous. I’ve never been a good student.”

She fixed her eyes on him. “Do you mind?”

“Mind what?”

“That I want to go to college.”

“No. Why would I mind?”

Deya studied him carefully, unsure whether to believe him. He could be pretending not to mind in order to trick her into thinking he was different than the previous suitors, more progressive. He could be telling her exactly what he thought she wanted to hear.

She straightened in her seat, avoiding his question. Instead she asked, “Why aren’t you a good student?”

“I’ve never really liked school,” he said. “But my parents insisted I apply to med school after college. They want me to be a doctor.”

“And do you want to be a doctor?”

Nasser laughed. “Hardly. I’d rather run the family business, maybe even open my own business one day.”

“Did you tell them that?”

“I did. But they said I had to go to college, and if not for medicine, then engineering or law.”

Deya looked at him. She had never known herself to feel anything besides anger and annoyance during these arrangements. One man had spent their entire conversation telling her how much money he earned at his gas station; another man had interrogated her about school, whether she intended to stay home and raise children, whether she would be willing to wear the hijab permanently and not only as part of her school uniform.

Still, Deya had questions of her own. What would you do to me if we married? Would you let me pursue my dreams? Would you leave me at home to raise the children while you worked? Would you love me? Would you own me? Would you beat me? She could have asked those questions aloud, but she knew people only told you what you wanted to hear. That to understand someone, you had to listen to the words they didn’t say, had to watch them closely.

“Why are you looking at me like that?” Nasser asked.

“Nothing, it’s just that . . .” She looked at her fingers. “I’m surprised your parents forced you to go to college. I’d assumed they’d let you make your own choices.”

“What makes you say that?”

“You know.” She met his eyes. “Because you’re a man.”

Nasser looked at her curiously. “Is that what you think? That I can do anything I want because I’m a man?”

“That’s the world we live in.”

He leaned forward, resting his hands on the table. It was the closest Deya had ever sat to a man, and she leaned back in her seat, pressing her hands between her thighs.

“You’re strange,” Nasser said.

She could feel her face flush, and she looked away. “Don’t let my grandmother hear you say that.”

“Why not? I meant it as a compliment.”

“She won’t see it that way.”

There was a pause, and Nasser reached for his teacup. “So,” he said after taking a sip. “How do you imagine your life in the future?”

“What do you mean?”

“What do you want, Deya Ra’ad?”

She couldn’t help but laugh. As if it mattered what she wanted. As if it were up to her. If it were up to her, she’d postpone marriage for another decade. She’d enroll in a study-abroad program, pick up and move to Europe, perhaps Oxford, spending her days in cafés and libraries with a book in one hand and a pen in the other. She’d be a writer, helping people understand the world through stories. But it wasn’t up to her. Her grandparents had forbidden her to attend college before marriage, and she didn’t want to ruin her reputation in the community by defying them. Or worse, be disowned, banned from seeing her sisters, the only home and family she had ever known. She was already abandoned and alone in so many ways; to lose her remaining roots would be too much to bear. She was afraid of the life her grandparents had planned for her, but even more afraid of the unknown. So she tucked her dreams away, did as she was told.

“I just want to be happy,” she told Nasser. “That’s all.”

“Well, that’s simple enough.”

“Is it?” She met his eyes. “If so, then why haven’t I seen it?”

“I’m sure you have. Your grandparents must be happy.”

Deya tried to keep from rolling her eyes. “Teta spends her days complaining about her life, how her children abandoned her, and Seedo barely comes home. Trust me. They’re miserable.”

Nasser shook his head. “Maybe you’re judging them too harshly.”

“Why? Are your parents happy?”

“Of course they are.”

“Do they love each other?”

“Of course they love each other! They’ve been married for over thirty years.”

“That doesn’t mean anything,” Deya scoffed. “My grandparents have been married for over fifty years, and they can’t stand the sight of each other.”

Nasser said nothing. From the expression on his face, Deya knew he found her pessimism unpleasant. But what should she have said to him instead? Should she have lied? It was already enough she was forced to live a life she didn’t want to live. Should she really begin a marriage with lies? When would it end?

Eventually Nasser cleared his throat. “You know,” he said. “Just because you can’t see the happiness in your grandparents’ life, that doesn’t mean they’re not happy. What makes one person happy doesn’t always work for someone else. Take my mother—she values family over everything. As long as she has my father and her children, she’s happy. But not everyone needs family, of course. Some people need money, others need companionship. Everyone is different.”

“And what do you need?” Deya asked.

“What?”

“What do you need to be happy?”

Nasser bit the inside of his lip. “Financial security.”

“Money?”

“No, not money.” He paused. “I want to have a stable career and live comfortably, maybe even retire young.”

She rolled her eyes. “Work, money, same thing.”

“Maybe so,” he said, blushing. “Why, what’s your answer?”

“Nothing.”

“That’s not fair. You have to answer the question. What would make you happy?”

“Nothing. Nothing would make me happy.”

He blinked at her. “What do you mean, nothing? Surely something must make you happy.”

She turned to look out the window, feeling his eyes follow her face. “I don’t believe in happiness.”

“That’s not true. Maybe you just haven’t found it yet.”

“It is true.”

“Is it because—” He stopped. “Do you think it’s because of your parents?”

She could tell he was trying to meet her eyes, but she kept them fixed on the window. “No,” she lied. “Not because of them.”

“Then why don’t you believe in happiness?”

He would never understand, even if she tried to explain. She turned to face him. “I just don’t believe in it, that’s all.”

He looked back at her with a glum expression. She wondered what he saw, whether he knew that if he opened her up, he would find, right behind her ribs, only a fist of rot and mud.

“I don’t think you really mean that,” he eventually said, smiling at her. “You know what I think?”

“What?”

“I think you’re just pretending to see how I’d react. You wanted to see if I’d make a run for it.”

“Interesting theory.”

“I think it’s true. In fact, I bet you do it often.”

“Do what?”

“Push people away so they won’t hurt you.” She looked away. “It’s okay. You don’t have to admit it.”

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.