Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

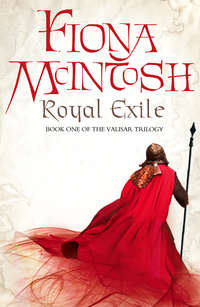

Kitabı oku: «Royal Exile»

Royal Exile

valisar: book one

FIONA McINToSH

For Will McIntosh, Jack McIntosh, Paige Klimentou

and Jack Caddy…

start walking towards your dreams today.

Whatever the dream, no matter how daring or grand, somebody will eventually achieve it. It might as well be you. Bryce Courtenay

Contents

Prologue Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty One Chapter Twenty Two Chapter Twenty Three Chapter Twenty Four Chapter Twenty Five Chapter Twenty Six Chapter Twenty Seven Chapter Twenty Eight Chapter Twenty Nine Chapter Thirty Chapter Thirty One Epilogue Glossary Acknowledgments Books By Fiona Mcintosh Copyright About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

King Ormond’s face was ashen. He wore the sunken, resigned expression of a man who knew he had but hours to live. Nevertheless, sitting on his horse, atop the mound overlooking the battlefield, his anger flared, his jaw grinding as he watched the horde from the plains make light work of his soldiers. His attention was riveted on one man: the enemy’s leader, who was easy to pick out in the fray, even from this distance. For while his warriors wore the distinctive colours of their tribe, inked all over their faces and bodies, this man’s skin was clean. His features, like his age, were indeterminate from this distance, but he fought with the speed and physical force of a man in his prime. And he led his men from the front, a sign of his bravado and courage.

‘Look at the arrogance!’ Ormond said, disbelief ringing in his voice. ‘Are we so pathetic that he doesn’t even care to take the precaution of armour? Does he have no fear?’

‘Majesty,’ one of his companions replied wearily. ‘I believe Loethar is driven by something more complex than a desire for victory.’

‘General Marth, what could possibly be more desirable than victory when one goes to war?’ the king challenged, staring down his offsider.

The general looked momentarily lost for words. He looked away towards the carnage, then back to his king. ‘Your highness, this man is not interested in simply winning. He is not looking to conscript a new army from the devastation of ours, or even to preserve much of the realm for his own needs. I sense he is only after humiliation for his enemy. He has shown the Set that his pattern is to kill everyone who carries a weapon against him. There is no mercy in his heart.’

The king shook his head, despair now haunting his expression. ‘I can’t let this continue. It has gone on long enough. He’s been on the rampage for four moons now. Dregon and Vorgaven are conquered and Cremond simply capitulated.’ He gave a sound of disgust. ‘The other realms in the Set that have been attacked have fallen no matter what reinforcements have been sent.’

Clearly forcing himself to remain calm despite the sounds of death below, the general took a breath. ‘As I counselled previously, majesty, it is not that he has an inexhaustible supply of fighters but that he has used his men with great cunning and insight. There has been nothing disorganised about his attack on the Set’s realms; it has been very strategic and we have not accorded him the respect he deserved. We should have taken him seriously when his men first started appearing. We should have sent our own men to help the Dregons and Vorgavese —’

‘For Lo’s sake, man! If Penraven didn’t why would we? Brennus obviously thought Ranuld could hold Vorgaven.’

‘We’re all neighbours, highness. We are the Set. We should have combined all our resources. Penraven has the largest army, the most well equipped army, the greatest number of weapons —’

‘Yes but still he didn’t! King Brennus chose not to send his men. Why? Because he trusted Ranuld to keep his end strong against this rabble upstart.’

General Marth looked away again, and like his king his gaze was helplessly drawn to the horde’s ruthless leader as his sword swung, hacking into one of their men’s necks. They saw the spume of blood explode and watched another life be given cheaply to the insatiable ruler of the plains tribes. The general turned back, a fresh look of fury on his face. ‘No, majesty. I don’t think the Valisar king trusts any of us. Forgive me, I know you consider him a friend, but King Brennus is not coming to anyone’s aid. I suspect he has seen the error of his confidence, knows the threat to Penraven is very real. In light of that we are expendable. His priority always has been, always will be, Penraven. He is saving his men for the final confrontation.’

King Ormond’s gaze narrowed. ‘He sent men to Dregon, he even —’

Marth shook his head sadly. ‘A token gesture, highness. We needed to combine our armies to chase this barbarian from our midst. Instead we brazenly allowed him the chance for his early and shocking victory against Dregon and Vorgaven — his audacity to fight not only on two fronts and two borders but to take both cities. His men are not mere rabble, highness. These are warriors … trained ones. We should have crushed him the moment he took his first footsteps into the Set.’

‘We all agreed to wait and see what his intentions were.’

‘Not all of us, highness,’ General Marth replied and the bitterness in his voice was tempered by sorrow. ‘We didn’t act fast enough. We all left it to each other.’

‘But who would have thought Cremond would not even offer the slightest resistance? Why? Do they want a tribal thug as their ruler?’ Marth shook his head, seemingly unable to offer any light on the Cremond capitulation although it was a longheld belief within the rest of the Set that Cremond, rarely considering itself as close to the other realms, often tended to behave in a contrary fashion. ‘And then who in his right mind marches across the region, ignoring Barronel, in order to take Vorgaven at the same time as Dregon? None of it makes sense.’

‘None of it makes sense because that was his intention. Loethar constantly caught us off guard. If we’d acted with speed at the outset we likely would have cut him off before he even established a foothold. Now he’s had these four moons to put our backs to the wall, to somehow convince Penraven — in its own arrogance — to wait and see what happens. Did we really think he was going to say “thank you” and go home?’

‘Brennus and I believed he’d seek terms. Granted, we’re both shocked at his victory, but we never anticipated that he’d go after the whole Set.’

‘I don’t know why, majesty. He didn’t ask permission to enter it. Why would he give us any opportunity to sit around a parley table with him? He probably can’t even speak the language!’ Marth hesitated briefly. But what was there to lose in finally speaking his mind? Careful to speak without accusation, he continued. ‘The Valisars have always considered themselves invincible and I doubt Brennus feels any differently. Don’t you see, your highness, that Brennus has allowed us to be the fodder? The rest of the realm has borne the brunt of Loethar’s ferocity and yet I think he’s deliberately saving the biggest, the best, for last. I don’t think it’s because he’s frightened of Penraven. Quite the contrary. He has been playing games, convincing Brennus that the tribes would run out of interest — another reason why Brennus has hesitated to send the full might of the Penravian army to stand by us. I sense Loethar has deliberately made himself appear to be that yob you called him earlier, when in fact he is a long way from being a dull-headed, thick-skinned ruffian who might tire of the spoils of war and head back to the plains, sated. He has shown himself to be a shrewd adversary and now, my king, he is ready to topple our realm. I admire him.’

Ormond sighed deeply and hung his head. ‘Call the retreat, general.’

‘No, King Ormond. Our men are going to die anyway. I suspect they would rather die fighting. It is more worthy to fall in the heat of battle and to a noble wound than on one’s knees pleading for one’s life. That’s what the barbarian did in Vorgaven; put people to the sword long after the battle cries had stopped echoing. I think our soldiers should go to Lo yelling their defiance.’

The king shook his head gravely. ‘But you are a general and I am a sovereign. It is our role to think brave and be brave to the last … to give our lives for our land. Perhaps some of these men might escape and survive to recount Barronel’s bravery to the last. For that hope alone, we should surrender.’

‘Please, King Ormond. Let us all perish if we must, but let us fight to the last man.’

Ormond set his chin grimly. ‘No. I took an oath when I was crowned that I would not knowingly allow any of my subjects to be killed if I could prevent it. I have to believe some of my people, however few, can be preserved in the chaos of retreat. Let the men run for their lives. But Lo help me, Marth, I will see the blood of the Valisars flour for this betrayal.’ His voice had become a growl. ‘Sound the retreat!’

Loethar’s teeth seemed to be the only part of him not drenched in the blood of his foe. But he knew that would soon change and while his limbs worked savagely, tirelessly, to deny his enemies another breath, his thoughts focused around drinking the blood of King Ormond of Barronel. For Ormond was all that stood between him and his true goal … Penraven.

All the preparation — two anni in the making — had been undertaken for the moment that he was so close to now he could almost taste it. All the relentless training had been worth it — the toughening of his warriors, the breeding of horses, stockpiling of food and water near the main Set border … But none of that could compare to his mental preparation. He had grown up on hate, loathing, bitterness, and rage, kept under control, channelled into the groundwork that led to the surprise concerted raid on two realms at the same time.

The overconfidence, the bursting ego of the Valisars demanded that they would never have believed for a moment they were under any serious threat. Not at the outset anyway. Which is why he’d acted as though he lacked any strategy or battle knowledge, traversing the Set covering unnecessary, almost senseless ground. He made sure his men behaved like the unruly rabble he wanted them to appear, even sending a quarter of them back to the Set’s main border, as though they were making a straggly return to their plains, no longer interested in the bloodlust.

And gradually he had streamed them back to the main vanguard, usually under cover of darkness, running alongside wild dogs of the plains that he had had trained since puppies, killing their parents so they knew and trusted only the smell of his men. These dogs made the sharpest of scouts. They knew how to range, how to move silently and how to smell even the vaguest threat of their enemy. Many times they warned the tribes’ various leaders to change course, to return to the main army via a different route. They were a large part of why Vorgaven, for instance, had thought it was facing three thousand men, when it was actually confronted by close on five thousand.

Time and again over the four moons Loethar had baffled his enemy, an enemy that was fuelled by such self-belief, and worse, such disdain for the horde of the plains, that it had essentially crippled itself.

Now Loethar grimaced as a man fell near his feet, the Barronel soldier’s sword slicing into Loethar’s leg before the soldier’s body fell. Fortunately, Loethar’s nimble, intelligent horse moved sideways, allowing the man to fall beneath the advancing warriors and other horses so that the body was quickly trampled until it no longer had a recognisable face. Loethar barely paid attention to the wound on his leg; it hurt but there was no time to consider the pain. His sword kept slashing a path through flesh and bone, moving him ever closer to his prize.

He suspected word had quickly been passed around that the shirtless, armour-less fighter was the one to bring down. But Stracker was always near, his Greens more savage than any of the other tribes.

Loethar saw one soldier’s head topple from his neck following one of Stracker’s tremendous blows. On the back swing of that same blow, another soldier had his outstretched arm hacked off just above the elbow. The soldier stared at the stump pumping blood and roared his despair, reaching down to pick up his fallen sword with the other hand.

‘He’s brave, I’ll give him that,’ Loethar called to his man as Stracker rammed his weapon into the soldier’s soft belly to finish him off.

‘Got to watch out for those sly two-handers, brother,’ Stracker yelled, slashing another man’s throat open with a practised swing.

‘They’ll call the retreat soon,’ Loethar called back, twisting his horse in a full circle, and killing two men in the motion.

‘No chance. Barronel plans to fight until every man falls, I reckon.’

Loethar managed to wink. ‘My amazing Trilla, here, for your stallion, says it will happen before you can kill another six of the enemy.’

Stracker smiled, his bloodstained face creasing in amusement. ‘Done! I’ve always liked that small, feisty horse of yours.’

‘She’s not yours yet, brother.’

‘Oh, but she will be. One!’ he called smugly as another Barronel soldier met his end. ‘Two,’ he added, slashing across the belly of another.

Stracker had made it to four when he and Loethar heard the unmistakeable sound of the Barronel retreat being sounded across the battlefield.

As Stracker roared his disapproval, Loethar laughed, but he was secretly relieved. He was tired and he knew the blood soaking his body wasn’t all his enemy’s. He too had taken some punishment. He had fought hard today at the front of the vanguard and the retreating backs of the Barronel force — gravely diminished as it was — was a sweet sight.

‘Round them up,’ he called to his senior tribesmen, trying to hide the weariness in his voice. ‘The Greens will join me in taking the surrender from General Marth. Reds and Blues, let them believe we are simply taking stock of their number. All will be killed later.’

‘And the king?’ Stracker asked, drawing alongside, still obviously miffed at losing the bet.

‘King Ormond I shall be sharing a drink with later. He will, of course, go to his god before this night is out, but first, Stracker, you owe me that fine horse.’

1

‘Could he do this?’ he wondered, as yet another wail began. He knew he had no choice if the Valisars were to survive.

Two great oak doors, carved with the family coat of arms, separated King Brennus from his wife’s groans and shrieks, but despite the sound being muffled, her agonised cries injured him nonetheless. He knew his beautiful and beloved Iselda would never have to forgive him because she would never know of his ruthlessness at what he planned for his own flesh and blood. He looked to his trusted legate and dropped his gaze, shaking his head. They were all servants to the crown — king included — and serve he must by presenting the infant corpse in order to protect the realm.

‘It never gets any easier, De Vis,’ he lamented.

De Vis nodded knowingly; he had lost his own wife soon after childbirth. ‘I can remember Eril’s screams as though they were yesterday.’ He hurried to add: ‘Of course, once the queen holds her child, majesty, her pain will disappear.’

They were both talking around the real issues — the murder of a newborn and the threat that their kingdom was facing its demise.

Brennus’s face drooped even further. ‘In this you are right, although I fear for all our children, De Vis. My wife brings into this world a new son who may never see his first anni.’

‘Which is why your plan is inspired, highness. We cannot risk Loethar having access to the power.’

‘If it is accessible at all in this generation. Leo shows no sign at this stage … and Piven …’ The king trailed off as another agonised shriek cut through their murmurs.

De Vis held his tongue but when silence returned and stretched between them, he said softly: ‘We can’t know for sure. Leo is still young — it may yet come to him — and the next prince may be bristling with it. We can’t risk either child falling into the wrong hands. And as for Piven, your highness, he is not of your flesh. We know he hardly possesses his faculties, majesty, let alone any power.’

The king’s grave face told his legate that Brennus agreed, that his mind was made up. Nevertheless he confirmed it aloud as though needing to justify his terrifying plan. ‘It is my duty to protect the Valisar inheritance. It cannot be tarnished by those not of the blood. I hope history proves me to be anything but the murderer I will appear if the truth ever outs. Is everything in place?’

‘Precisely to your specifications,’ De Vis answered.

Brennus could see the legate’s jaw working. De Vis was feeling the despair of what they were about to do as deeply as he was. ‘Your boys …’ the king muttered, his words petering out.

De Vis didn’t flinch. ‘Are completely loyal and will do their duty. You know that.’

‘Of course I know it, De Vis — they might as well be my own I know them so well — but they are too young for such grim tasks. I ask myself: could you do it? Could I? Can they?’

De Vis’s expression remained stoic. ‘They have to. You have said as much yourself. My sons will not let Penraven down.’

Brennus scowled. ‘Have you said anything yet?’

De Vis shook his head. ‘Until the moment is upon us, the fewer who know the better. The brief will also be better coming directly from you, majesty.’

Brennus winced as another scream came from behind the door, followed by a low groan that penetrated to the sunlit corridor where he and De Vis talked. He turned from the stone balustrade against which he had been leaning, looking out into the atrium that serviced the private royal apartments. Breathing deeply, he drank in the fragrance of daphne that the queen had personally planted in boxes hanging from the archways and took a long, sorrowful look at the light-drenched gardens below she had tended and made so beautiful. Trying for an heir had taken them on a torrid journey of miscarriages and disappointments. And then Leo had come along and, miraculously, had survived and flourished. But both Brennus and Iselda knew that a single heir was not enough, however, and so they had endured another three heartbreaking deaths in the womb.

It was as though Regor De Vis could read Brennus’s thoughts. ‘Do not fret over Piven, your highness. If the barbarian breaches our walls I doubt he will even glance at your adopted son.’

Brennus hoped his legate was right. Brennus was aware that Piven had made it quietly into the world and had remained mostly silent since then. These days odd noises, heartbreaking smiles and endless affection told everyone that Piven heard sound, though he could not communicate in any traditional way.

And now there was a new child who’d managed to somehow cling on to life, his heartbeat strong and fierce like the winged lion his family’s history sprang from. There had been so much excitement, so much to look forward to as little as six moons ago. And now everything had changed.

The ill-wind had blown in from the east, where one ambitious, creative warlord had united the rabble that made up the tribes who eked out an existence on the infertile plains. It had been almost laughable when Dregon sent news that it was under attack from the barbarians. It had sounded even more implausible when Vorgaven sent a similar missive.

De Vis could clearly read his mind. ‘How something we considered a skirmish could come to this is beyond me.’

‘I trusted everyone to hold their own against a mere tribal warlord!’

‘Our trust was a mistake, majesty … and so was our confidence in the Set’s strength. It should never have come to this. And, worse, we haven’t prepared our people. It’s only because word is coming through from relatives or traders from the other realms that they know Vorgaven has fallen, Dregon is crushed and cowardly Cremond simply handed over rule without so much as a squeak. I’m sure very few know how dire the situation is in Barronel.’

Brennus grimaced. ‘Ormond might hold.’

‘Only if we’d gone to his aid days ago, majesty. He will fall and our people will then know the truth as we prepare to fight.’

The king looked broken. ‘They’ve never believed, not for a second, that Penraven could fall. Food is plentiful, our army well trained and well equipped. Lo strike me, this is a tribal ruffian leading tribal rabble!’ But as much as the king wanted to believe otherwise, he knew the situation was dire. He no longer had options. ‘Summon Gavriel and Corbel,’ he said sadly.

De Vis nodded, turned on his heel and left the king alone to his dark thoughts. Minutes after his departure, Brennus heard the telltale lusty squall of a newborn. His new son had arrived. Not long later the senior midwife eased quietly from behind the doors. She curtsied low, a whimpering bundle of soft linens in her arms. But when she looked at the king her expression was one of terror, rather than delight.

‘I heard his battlecry,’ the king said, desperately trying to alleviate the tension but failing, frowning at her fear as she tiptoed, almost cringing, toward him with her precious cargo. ‘Is something wrong with my wife?’ he added, a fresh fear coursing through him.

‘No, not at all, your highness. The queen is fatigued, of course, but she will be well.’

‘Good. Let me see this new son of mine then,’ Brennus said, trying to sound gruff. His heart melted as he looked down at the baby’s tiny features, eyelids tightly clamped. The infant yawned and he felt an instant swell of love engulf him. ‘Hardly strapping but handsome all the same,’ he said, grinning despite his bleak mood, ‘with the dark features of the Valisars.’ He couldn’t disguise the pride in his voice.

The midwife’s voice was barely above a whisper when she spoke. ‘Sire, it … it is not a boy. You have been blessed with a daughter.’

Brennus looked at the woman as though she had suddenly begun speaking gibberish.

She hurried on in her anxious whisper. ‘She is beautiful but I must warn that she is frail due to her early arrival. A girl, majesty,’ she muttered with awe. ‘How long has it been?’

‘Show me,’ Brennus demanded, his jaw grinding to keep his own fears in check. The midwife obliged and he was left with no doubt; he had sired a girl. Wrapping her in the linens again, he looked mournfully at the old, knowing midwife — old enough to have delivered him nearly five decades ago. She knew about the Valisar line and what this arrival meant. How much worse could their situation get, he wondered, his mind instantly chaotic.

‘I fear she may not survive, majesty.’

‘I am taking her to the chapel,’ he said, ignoring the woman’s concerns.

Their attention was momentarily diverted by Piven scampering up, his dark curly hair its usual messy mop and his matching dark eyes twinkling with delight at seeing his father. But Piven gave everyone a similar welcome; it was obvious he made no distinction between man or woman, king or courtier. Everyone was a friend, deserving of a beaming, vacant salutation. Brennus affectionately stroked his invalid son’s hair.

The midwife tried to protest. ‘But the queen has hardly seen her. She said —’

‘Never mind what the queen instructs.’ Brennus reached for the baby. ‘Give her to me. I would hold the first Valisar princess in centuries. She will go straight to the chapel for a blessing in case she passes on. My wife will understand. Tell her I shall be back shortly with our daughter.’

Brennus didn’t wait for the woman’s reply. Cradling his daughter as though she were a flickering flame that could be winked out with the slightest draught, he shielded her beneath his cloak and strode — almost ran — to Penraven’s royal chapel, trailed by his laughing, clapping five-year-old boy. Inside he locked the door. His breathing had become laboured and shallow, and the fear that had begun as a tingle now throbbed through his body like fire.

The priest came and was promptly banished. Soon after a knock at the door revealed De Vis with his twin sons in tow, looking wide-eyed but resolute. Now tall enough to stand shoulder to shoulder alongside their father like sentries, strikingly similar and yet somehow clearly individual, they bowed deeply to their sovereign, while Piven mimicked the action. Although neither Gavriel nor Corbel knew what was afoot for them, they had obviously been told by their father that each had a special role to perform.

‘Bolt it,’ Brennus ordered as soon as the De Vis family was inside the chapel.

A glance to one son by De Vis saw it done. ‘Are we alone?’ he asked the king as Corbel drew the heavy bolt into place.

‘Yes, we’re secure.’

De Vis saw the king fetch a gurgling bundle from behind one of the pews and then watched his boys’ brows crinkle with gentle confusion although they said nothing. He held his breath in an attempt to banish his reluctance to go through with the plan. He could hardly believe this was really happening and that the king and he had agreed to involve the boys. And yet there was no other way, no one else to trust.

‘This is my newborn child,’ Brennus said quietly, unable to hide the catch in his voice.

The legate forced a tight smile although the sentiment behind it was genuine. ‘Congratulations, majesty.’ The fact that the baby was among them told him the plan was already in motion. He felt the weight of his own fear at the responsibility that he and the king were about to hand over; it fell like a stone down his throat to settle uncomfortably, painfully, in the pit of his stomach. Could these young men — still youthful enough that their attempts to grow beards and moustaches were a source of amusement — pull off the extraordinary plan that the king and he had hatched over this last moon? From the time at which it had become obvious that the Set could not withstand the force of Loethar’s marauding army.

They had to do this. He had to trust that his sons would gather their own courage and understand the import of what was being entrusted to them.

De Vis became aware of the awkward silence clinging to the foursome, broken only by the flapping of a sparrow that had become trapped in the chapel and now flew hopelessly around the ceiling, tapping against the timber and stone, testing for a way out. Piven, nearby, flapped his arms too, his expression vacant, unfocused.

De Vis imagined Brennus felt very much like the sparrow right now — trapped but hoping against hope for a way out of the baby’s death. There was none. He rallied his courage, for he was sure Brennus’s forlorn expression meant the king’s mettle was foundering. ‘Gavriel, Corbel, King Brennus wishes to tell you something of such grave import that we cannot risk anyone outside of the four of us sharing this plan. No one … do you understand?’

Both boys stared at their father and nodded. Piven stepped up into the circle and eyed each, smiling beatifically.

‘Have you chosen who takes which responsibility?’ Brennus asked, after clearing his throat.

‘Gavriel will take Leo, sire. Corbel will …’ he hesitated, not sure whether his own voice would hold. He too cleared his throat. ‘He will —’

Brennus rescued him. ‘Hold her, Corbel. This is a new princess for Penraven and a more dangerous birth I cannot imagine. I loathe passing this terrible responsibility to you but your father believes you are up to it.’

‘Why is she dangerous, your majesty?’ Corbel asked.

‘She is the first female to be born into the Valisars for centuries, the only one who might well be strong enough to live. Those that have been born in the past have rarely survived their first hour.’ Brennus shrugged sorrowfully. ‘We cannot let her be found by the tyrant Loethar.’

De Vis sympathised with his son. He could see that the king’s opening gambit was having the right effect in chilling Corbel but he was also aware that Brennus was circling the truth.

In fact he realised the king was distancing himself from it, already addressing Gavriel.

‘…must look after Leo. I cannot leave Penraven without an heir. I fear as eldest and crown prince he must face whatever is ahead — I cannot soften the blow, even though he is still so young.’

Gavriel nodded, and his father realised his son understood. ‘Your daughter does not need to face the tyrant — is this what you mean, your highness … that we can soften the blow for her, but not for the prince?’

De Vis felt something in his heart give. The boys would make him proud. He wished, for the thousandth time, that his wife had lived to see them. He pitied that she’d never known how Gavriel led and yet although this made Corbel seem weaker, he was far from it. If anything he was the one who was prepared to take the greatest risks, for all that he rarely shared what he was thinking. Gavriel did the talking for both of them and here again, he’d said aloud for everyone’s benefit what the king was finding so hard to say and Corbel refused to ask.

‘Yes,’ Brennus replied to the eldest twin. ‘We can soften the blow for the princess. She need not face Loethar. I have let the realm down by my willingness to believe in our invincibility. But no one is invincible, boys. Not even the barbarian. He is strong now, fuelled by his success — success that I wrongly permitted — but he too will become inflated by his own importance one day, by his own sense of invincibility. I have to leave it to the next generation to know when to bring him down.’