Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

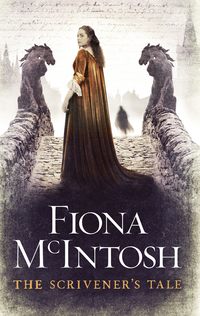

Kitabı oku: «Scrivener’s Tale»

For Stephanie Smith

… the fairy godmother of Australia’s

speculative fiction scene

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Also by Fiona McIntosh

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

He stirred, his consciousness fully engaged although he was unable to recall the last occasion anything had captivated his interest. How long had he waited in this numb acceptance that a shapeless, pointless eternity stretched ahead, with boredom his only companion? He was inconsequential, a nothingness. Existing, but not in a way that had worth or even acknowledgement … suspended between now and infinity. That was his punishment. Cyricus laughed without mirth or sound.

He was in this limbo because the goddess Lyana and her minions had been victorious several centuries previous, crushing the god Zarab. It had been the most intense confrontation that he could recall of all their cyclical battles, and Zarab’s followers, himself included, had been banished from the spiritual plane to wander aimlessly. He was a demon; not as powerful as his god, Zarab, but not as weak as most of the disciples and certainly more cunning, which is probably why he’d evaded being hunted down and destroyed. He and one other — a mere disciple — had survived Lyana’s wrath.

Cyricus remained an outlaw: a life, but not a life — no longer able to move in the plane of gods and never able to return to it, but he’d never given up hope. One day, he promised himself, he would learn a way to harness the power he needed, but not yet. He was not nearly strong enough and must content himself to exist without substance on the edge of worlds, and only his fury to keep him company.

But it was ill fate that he had recognised a fantastically powerful force emanating from the mortal plane; that force, he learned, was called the Wild. It sprawled to the northeast of an unfamiliar land called Morgravia. He’d been drifting in his insubstantial form for what might have been centuries, finally unwittingly veering into northern Briavel toward the natural phenomenon known as the Wild. It had sensed his evil and his interest long before he’d fully recognised its power: with the help of its keeper, Elysius, the Wild had driven the spirit of Cyricus and his minion into the universal Void. He could do nothing now but watch, bored, over more centuries, while mortals lived and died their short, trivial existences.

And then a young woman in Morgravia had done something extraordinary, fashioning a powerful magic so sly and sinister, so patient and cunning, that if he could he would have applauded her. It dragged him from disinterested slumber to full alertness, amusement even. This village woman, still languishing in her second decade, had crafted an incantation so powerful that she gave it an existence of its own: it had no master but it appeared to obey a set of rules that propelled it toward a single objective. Most curious of all, rather than cursing the man she loathed, Myrren had instead gifted her dark spell to his enemy, a boy.

Cyricus set aside his own situation and yearnings and gleefully focused his attention on the boy — plain, red-headed, forgettable if not for his name and title. He was Wyl Thirsk, the new hereditary general of the Morgravian Legion — forced to accept the role at his father’s untimely death — and he had no idea that his life had just taken a deviant path. Even Cyricus had no idea what the magic could do, but he could see it, shifting as a dark shadow within Thirsk. What would it do? What could it do? And when? Cyricus was centuries old; he was patient and had learned through Lyana’s punishment how to remain that way. Whatever magic it was that the young woman Myrren had cast, he was sure it would, one day, show itself.

It took five annums — a mere blink to him — before Cyricus could see the effect of Myrren’s gift. When it finally quickened within the young man and demonstrated its capacity, Cyricus mentally closed his eyes in awe.

It was a beautiful magic answerable to no-one.

And it was simple, elegant, brutal.

Wyl Thirsk moved haplessly, and savagely, through different lives while the magic of Myrren raged, always seeking that one person its creator hunted. Cyricus watched, fascinated, as the magic wreaked its havoc: changing lives, rearranging the course of Morgravia’s, Briavel’s and even the Razor Kingdom’s history.

And then at the height of his amusement it stopped. The spell laid itself to rest as abruptly as it had begun, although the land in which it had raged was an entirely changed place. Four kings had died in its time — two of those directly because of it — and a new empire had emerged. And the target of Myrren’s gift — and her curse — was finally destroyed.

In spite of the disappointment at his entertainment being cut short Cyricus had developed a respect for the magic. It was not random, it was extremely focused and its goal had been reached … revenge on King Celimus of Morgravia had been exacted in the most fantastic of manners.

The magic eased away from its carrier, Wyl Thirsk. However, it could never die once cast, of course, and Cyricus watched it finally pull itself into a small kernel until it was barely there, drifting around as he once had, attached to no-one and nothing — or so he thought — until his tireless observation refuted that presumption.

The magic did belong somewhere and it wanted to return there — to its spiritual home. But it was not permitted. And almost like an orphaned creature he could sense its longing, he could feel a kinship — they were both seemingly evil, both lost and unwanted, each unable to have substance, and yet both unable to disappear entirely into death.

He felt empathy! A unique moment of awakening for Cyricus.

In following Myrren’s gift, his gaze fell upon the Wild once again, and what he now discovered brought new fury, a rage like he had not felt since he was first defeated alongside Zarab. He learned that Myrren had been the child of Elysius! Her magic was born of him! The Wild protected them! But it repelled her savage, killing magic that she’d designed with only darkness in her intent.

Suddenly Cyricus had a purpose and it was Myrren’s cursed gift that gave him an idea: he would escape this prison of eternal suspended existence. The magic was there — homeless, idle, useless, ignored. He would lure it — make it notice him, welcome it even and then harness it. But he needed help.

He would need Aphra, his willing slave and undeniably adoring minion. He had longed for her carnal ways if not her vaguely irritating company. She had always worshipped him. He had toyed with her when it suited, had controlled her utterly. She would still do anything for him — torch, maim, pillage and kill for him. He liked her pliable emotions, her cunning — which, though no match for his, was admirable — and now he finally had good use for her. She’d been calling to him for decades — so many years he’d lost count and hadn’t cared to know. He’d had no reason to communicate.

But now he could see that dear love-blinded Aphra was his way back into some sort of life. She would provide him with what he lacked once he had captured the magic, understood it and moulded it to suit his needs. Myrren’s magic was his priority; the rest would fall into place.

And so Cyricus remained close to the three realms and began to plot while they became one; he watched the empire rise and flourish, and then begin to wane as factions within its trio of realms erupted to start dismantling what Emperor Cailech and his Empress Valentyna had given so much to achieve. Cyricus couldn’t care less. They could all go to war and he would enjoy watching the carnage … they could limp on, remaining allied but hating one another and it would make not a jot of difference to Cyricus.

All that mattered to him was being able to return to substantial form again — he wanted to be seen again, for his voice to be heard again. And he wanted to make this land — and the Wild that protected it, that had flicked him into the Void — pay for his suffering. His patience knew no bounds and while he tirelessly worked toward his aim he watched as heir upon heir sat on the Morgravian throne, unaware that theirs might be the reign that felt the full impact of his hungry revenge.

ONE

In the stillness that came in the hour before dawn, when Paris was at its quietest, a dark shape moved silently through the frigid winter air.

It landed soundlessly on a balcony railing that was crusted with December frost and stared through the window, where the softest glow of a bedside lamp illuminated the face of a sleeping man. The man was not at rest though.

Gabe was dreaming, his eyes moving rapidly behind his lids as the tension within the world of his dream escalated. It was not his favourite dream of being in the cathedral but it was familiar all the same and it frightened him. He’d taught himself to recognise the nightmare whenever and without any warning he slipped into the scene; only rarely did its memory linger. Most times the details of the dream fell like water through his fingers. Gone in the blink of surfacing to an alertness of his reality.

Here it was again: You’re in the nightmare, Gabe, his protective subconscious prodded. Start counting back from ten and open your eyes.

Ten …

Gabe felt the knife enter flesh, which surrendered so willingly; blood erupted in terrible warmth over his fist as it gripped the hilt. He felt himself topple, begin to fall …

… six … five …

He awoke with a dramatic start.

His heart was pounding so hard in his chest he could feel the angry drum of it against his ribcage. This was one of those rare occasions when vague detail lingered. And it felt so real that he couldn’t help but look at his hands for tangible evidence, expecting to see them covered with blood.

He tried to slow his breathing, checking the clock and noticing it was only nearing six and the sky was still dark in parts. He was parched. Gabe sat up and reached for the jug and tumbler he kept at his bedside and drank two glasses of water greedily. The hand that had held the phantasmic knife still trembled slightly. He shook his head in disgust.

Who had been the victim?

Why had he killed?

He blinked, deep in thought: could it be symbolic of the deaths that had affected him so profoundly? But he also hazily recalled that in his nightmare death had been welcomed by the victim.

Gabe shivered, his body clammy, and allowed the time for his breathing to become deeper and his heartbeat to slow. Paris was on the edge of winter; dawn would break soon but it remained bitingly cold — he could see ice crystals in the corners of the windows outside.

He swung his legs over the side of the bed and deliberately didn’t reach for his hoodie or brushed cotton pyjama bottoms. Gingerly climbing down from the mezzanine bedroom he tiptoed naked in the dark to open the French doors. Something darker than night skittered away but he convinced himself he’d imagined it for there was no sign once he risked stepping out onto the penthouse balcony.

The cold tore at his skin, but at least, shivering uncontrollably, he knew he was fully awake in Paris, in the 6th arrondissement … and his family had been dead for six years now. Gabe had been living here for not quite four of those, after one year in a wilderness of pain and recrimination and another losing himself in restless journeying in a bid to escape the past and its torment.

He had been one of Britain’s top psychologists. His public success was mainly because of the lodge he’d set up in the countryside where emotionally troubled youngsters could stay and where, amidst tranquil surrounds, Gabe would work to bring a measure of peace to their minds. There was space for a menagerie of animals for the youngsters to interact with or care for, including dogs and cats, chickens, pigs, a donkey. Horse riding at the local stables, plus hiking, even simple cake- and pie-baking classes, were also part of the therapy, diverting a patient’s attention outward and into conversation, fun, group participation, bonding with others, finding safety nets for the wobbly times on the tightropes of anxiety.

It was far more complex than that, of course, with other innovative approaches being used as well — everything from psychodynamic music to transactional therapies. Worried parents and carers, teachers and government agencies had all marvelled at his success in strengthening and fortifying the ability of his young charges to deal with their ‘demons’.

Television reporters, journalists and the grapevine, however, liked to present him as a folk hero — a modern-day Pied Piper, using simple techniques like animal husbandry. It allowed his detractors to claim his brand of therapy and counsel was not rooted in academia. Even so, Gabe’s legend had grown. Big companies knocked on his door: why didn’t he join their company and show them how to market to teens, or perhaps they could sponsor the lodge? He refused both options but that didn’t stop his peers criticising him or his status increasing to world acclaim. Or near enough.

Fate is a fickle mistress, they say, and she used his success to kill not only his stellar career but also his family, in a motorway pile-up while on their way to visit his wife’s family for Easter.

The real villain was not his fast, expensive German car but the semi-trailer driver whose eyelids fate had closed, just for a moment. The tired, middle-aged man pushed himself harder than he should have in order to sleep next to his wife and be home to kiss his son good morning; he set off the chain of destruction on Britain’s M1 motorway in the Midlands one terrible late-winter Thursday evening.

The pile-up had occurred on a frosty, foggy highway and had involved sixteen vehicles and claimed many lives, amongst them Lauren and Henry. For some inexplicable reason the gods had opted to throw Gabe four metres clear of the carnage, to crawl away damaged and bewildered. He might have seen the threat if only he hadn’t turned to smile at his son …

He faced the world for a year and then he no longer wanted to face it. Gabe had fled to France, the homeland of his father, and disappeared with little more than a rucksack for fifteen months, staying in tiny alpine villages or sipping aniseed liquor in small bars along the coastline. In the meantime, and on his instructions, his solicitor had sold the practice and its properties, as well as the sprawling but tasteful mansion in Hurstpierpoint with the smell of fresh paint still evident in the new nursery that within fourteen weeks was to welcome their second child.

He was certainly not left poor, plus there was solid income from his famous dead mother’s royalties and also from his father’s company. In his mid-thirties he found himself in Paris with a brimming bank account, a ragged beard, long hair and, while he couldn’t fully call it peace of mind, he’d certainly made his peace with himself regarding that traumatic night and its losses. He believed the knifing dream was symbolic of the death of Lauren and Henry — as though he had killed them with a moment’s inattention.

He thought the nightmare was intensifying, seemingly becoming clearer. He certainly recalled more detail today than previously, but he also had to admit it was becoming less frequent.

The truth was that most nights now he slept deeply and woke untroubled. His days were simple. He didn’t need a lot of money to live day to day now that the studio was paid for and furnished. He barely touched his savings in fact, but he worked in a bookshop to keep himself distracted and connected to others, and although he had become a loner, he was no longer lonely. The novel he was working on was his main focus, its characters his companions. He was enjoying the creative process, helplessly absorbed most evenings in his tale of lost love. A publisher was already interested in the storyline, an agent pushing him to complete the manuscript. But Gabe was in no hurry. His writing was part of his healing therapy.

He stepped back inside and closed the windows. He found comfort in knowing that the nightmare would not return for a while, along with the notion that winter was announcing itself loudly. He liked Paris in the colder months, when the legions of tourists had fled, and the bars and cafés put their prices back to normal. He needed to get a hair cut … but what he most needed was to get to Pierre Hermé and buy some small cakes for his colleagues at the bookshop.

Today was his birthday. He would devour a chocolate- and a coffee-flavoured macaron to kick off his mild and relatively private celebration. He showered quickly, slicked back his hair, which he’d only just noticed was threatening to reach his shoulders now that it was untied, dressed warmly and headed out into the streets of Saint-Germain. There were times when he knew he should probably feel at least vaguely self-conscious about living in this bourgeois area of Paris but then the voice of rationality would demand one reason why he should suffer any embarrassment. None came to mind. Famous for its creative residents and thinkers, the Left Bank appealed to his sense of learning, his joy of reading and, perhaps mostly, his sense of dislocation. Or maybe he just fell in love with this neighbourhood because his favourite chocolate salon was located so close to his studio … but then, so was Catherine de Medici’s magnificent Jardin du Luxembourg, where he could exercise, and rather conveniently, his place of work was just a stroll away.

He was the first customer into Pierre Hermé at ten as it opened. Chocolate was beloved in Britain but the Europeans, and he believed particularly the French, knew how to make buying chocolate an experience akin to choosing a good wine, a great cigar or a piece of expensive jewellery. Perhaps the latter was taking the comparison too far, but he knew his small cakes would be carefully picked up by a freshly gloved hand, placed reverently into a box of tissue, wrapped meticulously in cellophane and tied with ribbon, then placed into another beautiful bag.

The expense for a single chocolate macaron — or indeed any macaron — was always outrageous, but each bite was worth every euro.

‘Bonjour, monsieur … how can I help you?’ the woman behind the counter asked with a perfect smile and an invitation in her voice.

He wouldn’t be rushed. The vivid colours of the sweet treats were mesmerising and he planned to revel in a slow and studied selection of at least a dozen small individual cakes. He inhaled the perfume of chocolate that scented the air and smiled back at the immaculately uniformed lady serving him. Today was a good day; one of those when he could believe the most painful sorrows were behind him. He knew it was time to let go of Lauren and Henry — perhaps as today was his birthday it was the right moment to cut himself free of the melancholy bonds he clung to and let his wife and two dead children drift into memory, perhaps give himself a chance to meet someone new to have an intimate relationship with. ‘No time like the present’, he overheard someone say behind him to her companion. All right then. Starting from today, he promised himself, life was going to be different.

Cassien was doing a handstand in the clearing outside his hut, balancing his weight with great care, bending slowly closer to the ground before gradually shifting his weight to lower his legs, as one, until he looked to be suspended horizontally in a move known simply as ‘floating’. He was concentrating hard, working up to being able to maintain the ‘float’ using the strength of one locked arm rather than both.

Few others would risk the dangers and loneliness of living in this densely forested dark place which smelled of damp earth, although its solemnity was brightened by birds flittering in and around its canopy of leafy branches. His casual visitors were a family of wolves that had learned over years to trust his smell and his quiet observations. He didn’t interact often with them, other than with one. A plucky female cub had once lurched over to him on unsteady legs and licked his hand, let him stroke her. They had become soul mates since that day. He had known her mother and her mother’s mother but she was the first to touch him, or permit being touched.

Cassien knew how to find the sun or wider open spaces if he needed them. But he rarely did. This isolated part of the Great Forest had been his home for ten summers; he hardly ever had to use his voice and so he read aloud from his few books — which were exchanged every three moons — for an hour each day. They were sent from the Brotherhood’s small library and he knew each book’s contents by heart now, but it didn’t matter. It also didn’t matter to him whether he was reading Asher’s Compendium about medicinal therapies or Ellery’s Ephemeris, with its daily calendar of the movement of heavenly bodies. He was content to read anything that improved his knowledge and allowed him to lose his thoughts to learning. He was, however, the first to admit to his favourite tome being The Tales of Empire, written a century previously by one of the Brothers with a vivid imagination, which told stories of heroism, love and sorcery.

At present he was immersed in the Enchiridion of Laslow and the philosophical discourses arising from the author’s lifetime of learning alongside the scholar Solvan Jenshan, one of the initiators of the Brotherhood and advisor to Emperor Cailech. Cassien loved the presence of these treasures in his life, imagining the animal whose skin formed the vellum to cover the books, the trees that gave their bark to form the rough paper that the ink made from the resin of oak galls would be scratched into. Imagining each part of the process of forming the book and the various men involved in them, from slaughtering the lamb to sharpening the quill, felt somehow intrinsic to keeping him connected with mankind. Someone had inked these pages. Another had bound this book. Others had read from it. Dozens had touched it. People were out there beyond the forest living their lives. But only two knew of his existence here and he had to wonder if Brother Josse ever worried about him.

Cassien lifted his legs to be in the classic handstand position before he bounced easily and fluidly regained his feet. He was naked, had worked hard, as usual, so a light sheen of perspiration clung to every highly defined muscle … it was as though Cassien’s tall frame had been sculpted. His lengthy, intensive twice-daily exercises had made him supple and strong enough to lift several times his own body weight.

He’d never understood why he’d been sent away to live alone. He’d known no other family than the Brotherhood — fifteen or so men at any one time — and no other life but the near enough monastic one they followed, during which he’d learned to read, write and, above all, to listen. Women were not forbidden but women as lifelong partners were. And they were encouraged to indulge their needs for women only when they were on tasks that took them from the Brotherhood’s premises; no women were ever entertained within. Cassien had developed a keen interest in women from age fifteen, when one of the older Brothers had taken him on a regular errand over two moons and, in that time, had not had to encourage Cassien too hard to partake in the equally regular excursions to the local brothel in the town where their business was conducted. During those visits his appetite for the gentler sex was developed into a healthy one and he’d learned plenty in a short time about how to take his pleasure and also how to pleasure a woman.

He’d begun his physical training from eight years and by sixteen summers presented a formidable strength and build that belied how lithe and fast he was. He’d overheard Brother Josse remark that no other Brother had taken to the regimen faster or with more skill.

Cassien washed in the bucket of cold water he’d dragged from the stream and then shook out his black hair. He’d never known his parents and Josse couldn’t be drawn to speak of them other than to say that Cassien resembled his mother and that she had been a rare beauty. That’s all Cassien knew about her. He knew even less about his father; not even the man’s name.

‘Make Serephyna, whom we honour, your mother. Your father must be Shar, our god. The Brothers are your family, this priory your home.’

Brother Josse never wearied of deflecting his queries and finally Cassien gave up asking.

He looked into the small glass he’d hung on the mud wall. Cassien combed his hair quickly and slicked it back into a neat tail and secured it. He leaned in closer to study his face, hoping to make a connection with his real family through the mirror; his reflection was all he had from which to create a face for his mother. His features appeared even and symmetrical — he allowed that he could be considered handsome. His complexion showed no blemishes while near black stubble shadowed his chin and hollowed cheeks. Cassien regarded the eyes of the man staring back at him from the mirror and compared them to the rock pools near the spring that cascaded down from the Razor Mountains. Centuries of glacial powder had hardened at the bottom of the pools, reflecting a deep yet translucent blue. He wondered about the man who owned them … and his purpose. Why hadn’t he been given missions on behalf of the Crown like the other men in the Brotherhood? He had been superior in fighting skills even as a lad and now his talent was as developed as it could possibly be.

Each new moon the same person would come from the priory; Loup was mute, fiercely strong, unnervingly fast and gave no quarter. Cassien had tried to engage the man, but Loup’s expression rarely changed from blank.

His task was to test Cassien and no doubt report back to Brother Josse. Why didn’t Josse simply pay a visit and judge for himself? Once in a decade was surely not too much to ask? Why send a mute to a solitary man? Josse would have his reasons, Cassien had long ago decided. And so Loup would arrive silently, remaining for however long it took to satisfy himself that Cassien was keeping sharp and healthy, that he was constantly improving his skills with a range of weapons, such as the throwing arrows, sword, or the short whip and club.

Loup would put Cassien through a series of contortions to test his strength, control and suppleness. They would run for hours to prove Cassien’s stamina, but Loup would do his miles on horseback. He would check Cassien’s teeth, that his eyes were clear and vision accurate, his hearing perfect. He would even check his stools to ensure that his diet was balanced. Finally he would check for clues — ingredients or implements — that Cassien might be smoking, chewing or distilling. Cassien always told Loup not to waste his time. He had no need of any drug. But Loup never took his word for it.

He tested that a blindfolded Cassien — from a distance — was able to gauge various temperatures, smells, Loup’s position changes, even times of the day, despite being deprived of the usual clues.

Loup also assessed pain tolerance, the most difficult of sessions for both of them: stony faced, the man of the Brotherhood went about his ugly business diligently. Cassien had wept before his tormentor many times. But no longer. He had taught himself through deep mind control techniques to welcome the sessions, to see how far he could go, and now no cold, no heat, no exhaustion, no surface wound nor sprained limb could stop Cassien completing his test. A few moons previously the older man had taken his trial to a new level of near hanging and near drowning in the space of two days. Cassien knew his companion would not kill him and so it was a matter of trusting this fact, not struggling, and living long enough for Loup to lose his nerve first. Hanging until almost choked, near drowning, Cassien had briefly lost consciousness on both tests but he’d hauled himself to his feet finally and spat defiantly into the bushes. Loup had only nodded but Cassien had seen the spark of respect in the man’s expression.