Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Book of Swords: Part 1», sayfa 3

All at once, we were in the middle of another great revival of interest in Sword & Sorcery, one which has so far not faded again as we progress deeper into the second decade of the twenty-first century. Already there’s another generation of newer writers such as Ken Liu, Rich Larson, Carrie Vaughn, Aliette de Bodard, Lavie Tidhar, and others, taking up the challenges of the form, and sometimes evolving it in unexpected directions—and behind them are yet more new generations.

So, call it Sword & Sorcery, or call it Epic Fantasy, it looks like this kind of story is going to be around for a while for us to enjoy.

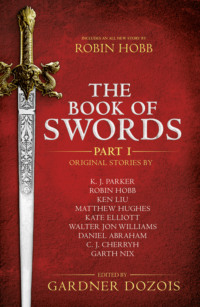

I’ve edited other anthologies with new Sword & Sorcery stories in them, such as the Jack Vance tribute anthology Songs of the Dying Earth, Warriors, Dangerous Women, and Rogues (all edited with that other big-time Sword & Sorcery fan, George R.R. Martin), but I’ve always wanted to edit an anthology of nothing but such stories, which is what I’ve done here with The Book of Swords, bringing you the best work of some of the best writers working in the form today, from across several different literary generations.

I hope that you enjoy it. And it’s my hope that to some young kid out there, it will prove as enthralling and inspirational as Unknown and Swords & Sorcery did to me back in 1963—and so a new Sword & Sorcery fan will be born, to carry the love of this kind of swashbuckling fantasy tale on into the distant future.

K. J. Parker

One of the most inventive and imaginative writers working in fantasy today, K. J. Parker is the author of the bestselling Engineer trilogy (Devices and Desires, Evil for Evil, The Escapement) as well as the previous Fencer (The Colours in the Steel, The Belly of the Bow, The Proof House) and Scavenger (Shadow, Pattern, Memory) trilogies. His short fiction has been collected in Academic Exercises, and he has twice won the World Fantasy Award for Best Novella, for “Let Maps to Others” and “A Small Price to Pay for Birdsong.” His other novels include Sharps, The Company, The Folding Knife, and The Hammer. His most recent novels are Savages and The Two of Swords. K. J. Parker also writes under his real name, Tom Holt. As Holt, he has published Expecting Someone Taller, Who’s Afraid of Beowulf, Ye Gods!, and many other novels.

Here he gives us a compelling look at a determined pupil seeking out a master for instruction—with some surprising results.

THE BEST MAN WINS

He was in my light. I didn’t look up. “What do you want?” I said.

“Excuse me, but are you the sword-smith?”

There are certain times when you have to concentrate. This was one of them. “Yes. Go away and come back later.”

“I haven’t told you what I—”

“Go away and come back later.”

He went away. I finished what I was doing. He came back later. In the interim, I did the third fold.

Forge-welding is a horrible procedure and I hate doing it. In fact, I hate doing all the many stages that go to creating the finished object; some of them are agonisingly difficult, some are exhausting, some of them are very, very boring; a lot of them are all three, it’s your perfect microcosm of human endeavour. What I love is the feeling you get when you’ve done them, and they’ve come out right. Nothing in the whole wide world beats that.

The third fold is—well, it’s the stage in making a sword-blade when you fold the material for the third time. The first fold is just a lot of thin rods, some iron, some steel, twisted together then heated white and forged into a single strip of thick ribbon. Then you twist, fold, and do it again. Then you twist, fold, and do it again. The third time is usually the easiest; the material’s had most of the rubbish beaten out of it, the flux usually stays put, and the work seems to flow that bit more readily under the hammer. It’s still a horrible job. It seems to take forever, and you can wreck everything you’ve done so far with one split second of carelessness; if you burn it or let it get too cold, or if a bit of scale or slag gets hammered in. You need to listen as well as look—for that unique hissing noise that tells you that the material is just starting to spoil but isn’t actually ruined yet; that’s the only moment at which one strip of steel will flow into another and form a single piece—so you can’t chat while you’re doing it. Since I spend most of my working day forge-welding, I have this reputation for unsociability. Not that I mind. I’d be unsociable if I were a ploughman.

He came back when I was shovelling charcoal. I can talk and shovel at the same time, so that was all right.

He was young, I’d say about twenty-three or -four; a tall bastard (all tall people are bastards; I’m five feet two) with curly blond hair like a wet fleece, a flat face, washed-out blue eyes, and a rather girly mouth. I took against him at first sight because I don’t like tall, pretty men. I put a lot of stock in first impressions. My first impressions are nearly always wrong. “What do you want?” I said.

“I’d like to buy a sword, please.”

I didn’t like his voice much, either. In that crucial first five seconds or so, voices are even more important to me than looks. Perfectly reasonable, if you ask me. Some princes look like rat-catchers, some rat-catchers look like princes, though the teeth usually give people away. But you can tell precisely where a man comes from and how well-off his parents were after a couple of words; hard data, genuine facts. The boy was quality—minor nobility—which covers everything from overambitious farmers to the younger brothers of dukes. You can tell immediately by the vowel sounds. They set my teeth on edge like bits of grit in bread. I don’t like the nobility much. Most of my customers are nobility, and most of the people I meet are customers.

“Of course you do,” I said, straightening my back and laying the shovel down on the edge of the forge. “What do you want it for?”

He looked at me as though I’d just leered at his sister. “Well, for fighting with.”

I nodded. “Off to the wars, are you?”

“At some stage, probably, yes.”

“I wouldn’t if I were you,” I said, and I made a point of looking him up and down, thoroughly and deliberately. “It’s a horrible life, and it’s dangerous. I’d stay home if I were you. Make yourself useful.”

I like to see how they take it. Call it my craftsman’s instinct. To give you an example; one of the things you do to test a really good sword is make it come compass—you fix the tang in a vise, then you bend it right round in a circle, until the point touches the shoulders; let it go, and it should spring back absolutely straight. Most perfectly good swords won’t take that sort of abuse; it’s an ordeal you reserve for the very best. It’s a horrible, cruel thing to do to a lovely artefact, and it’s the only sure way to prove its temper.

Talking of temper; he stared at me, then shrugged. “I’m sorry,” he said. “You’re busy. I’ll try somewhere else.”

I laughed. “Let me see to this fire and I’ll be right with you.”

The fire rules my life, like a mother and her baby. It has to be fed, or it goes out. It has to be watered—splashed round the edge of the bed with a ladle—or it’ll burn the bed of the forge. It has to be pumped after every heat, so I do all its breathing for it, and you can’t turn your back on it for two minutes. From the moment when I light it in the morning, an hour before sunrise, until the point where I leave it to starve itself to death overnight, it’s constantly in my mind, like something at the edge of your vision, or a crime on your conscience; you’re not always looking at it, but you’re always watching it. Given half a chance, it’ll betray you. Sometimes I think I’m married to the damn thing.

Indeed. I never had time for a wife. I’ve had offers; not from women, but from their fathers and brothers—he must be worth a bob or two, they say to themselves, and our Doria’s not getting any younger. But a man with a forge fire can’t fit a wife into his daily routine. I bake my bread in its embers, toast my cheese over it, warm a kettle of water twice a day to wash in, dry my shirts next to it. Some nights, when I’m too worn-out to struggle the ten yards to my bed, I sit on the floor with my back to it and go to sleep, and wake up in the morning with a cricked neck and a headache. The reason we don’t quarrel all the time is that it can’t speak. It doesn’t need to.