Kitabı oku: «Letters to a Prisoner of War»

Gerda Nischan

Letters to a Prisoner of War

AUGUST VON GOETHE LITERATURVERLAG

FRANKFURT A.M. • WEIMAR • LONDON • NEW YORK

Die neue Literatur, die – in Erinnerung an die Zusammenarbeit Heinrich Heines und Annette von Droste-Hülshoffs mit der Herausgeberin Elise von Hohenhausen – ein Wagnis ist, steht im Mittelpunkt der Verlagsarbeit.

Das Lektorat nimmt daher Manuskripte an, um deren Einsendung das gebildete Publikum gebeten wird.

©2014 FRANKFURTER LITERATURVERLAG FRANKFURT AM MAIN

Ein Unternehmen der Holding

FRANKFURTER VERLAGSGRUPPE

AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT

In der Straße des Goethehauses/Großer Hirschgraben 15

D-60311 Frankfurt a/M

Tel. 069-40-894-0 ▪ Fax 069-40-894-194

E-Mail lektorat@frankfurter-literaturverlag.de

Medien- und Buchverlage

DR. VON HÄNSEL-HOHENHAUSEN

seit 1987

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet abrufbar über http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Websites der Verlagshäuser der

Frankfurter Verlagsgruppe:

www.frankfurter-verlagsgruppe.de

www.frankfurter-literaturverlag.de

www.frankfurter-taschenbuchverlag.de

www.publicbookmedia.de

www.august-goethe-literaturverlag.de

www.fouque-literaturverlag.de

www.weimarer-schiller-presse.de

www.deutsche-hochschulschriften.de

www.deutsche-bibliothek-der-wissenschaften.de

www.haensel-hohenhausen.de

www.prinz-von-hohenzollern-emden.de

Dieses Werk und alle seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt.

Nachdruck, Speicherung, Sendung und Vervielfältigung in jeder Form, insbesondere Kopieren, Digitalisieren, Smoothing, Komprimierung, Konvertierung in andere Formate, Farbverfremdung sowie Bearbeitung und Übertragung des Werkes oder von Teilen desselben in andere Medien und Speicher sind ohne vorgehende schriftliche Zustimmung des Verlags unzulässig und werden auch strafrechtlich verfolgt.

Lektorat: Katrin Schmidbauer

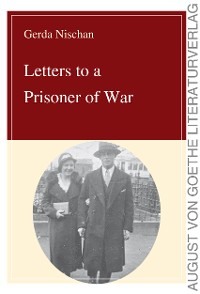

Titelbild: Barbara and Otto Baumann (a.1934), parents of Gerda Nischan

Parts of this volume were first published in TRANS-LIT 2, vol.XVI/Nos. 1. and 2 Spring and Fall 2010.

Gerda Nischan Papers (#1000.1) East Carolina Manuscript Collection, Special Collections Department, J.Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC. USA

ISBN 978-3-8372-1578-6

Die Autoren des Verlags unterstützen den Bund Deutscher Schriftsteller e.V., der gemeinnützig neue Autoren bei der Verlagssuche berät. Wenn Sie sich als Leser an dieser Förderung beteiligen möchten, überweisen Sie bitte einen – auch gern geringen – Beitrag an die Volksbank Dreieich, Kto. 7305192, BLZ 505 922 00, mit dem Stichwort „Literatur fördern“. Die Autoren und der Verlag danken Ihnen dafür!

For John,

Vermont forever

Table of Contents

Preface

Part I ‒ Letters of the parents

Part II – Autobiography of a Child

Index

Preface

My parents were ordinary people who led ordinary lives. They met on a train somewhere in the Palatinate, my mother on her way home to her family and my father on his way to America. He had lost both his parents by the age of eleven; first, his mother, who died in childbirth, and, a year later, his father, dying of grief.

My mother, born in the Palatinate in 1910, had two siblings and had enjoyed a happy early childhood. That changed rapidly when her father was killed in World War I, and her mother married his brother, a widower with three children, a year later. Three more children were born to the parents and before long there were nine children to take care of, which changed life in that household rapidly. My mother often had tears in her eyes when she talked about that time. Where there had been love and kindness before there was now open hatred and competition between the children, and my mother never warmed up to the new man she was supposed to call father and never addressed him as such. As a result he was often extremely strict and cruel towards her. Her dream of becoming a teacher had to be buried.

Life was hard after the end of the war. What once had been a quiet, loving family life turned into a fight for survival.

My father, born in 1905, also in the Palatinate, had been mistreated by the relatives who reared him after both his parents had died. This experience helped to convince him to go to America to find a better life. He was a baker by profession, specializing in all sorts of bread baking and the fine art of cakes and pastries, and his dream was to own his own bakery and coffee-house, one day. A distant relative had gone to America before him, and with his help my father sailed, at age 23, to America. The year was 1928.

The girl that he had met on the train was on his mind all the time while working in Rochester as a baker. He had asked her if he would be allowed to send her a postcard from America and so he did.

He wrote more than one postcard, soon they exchanged letters. They fell in love. After two years of letters across the ocean, my father asked her to marry him; they should live in America, he felt, since life in Germany at that time was so uncertain. The only surviving letter from my father during that period is dated September 24, 1930. My mother had burned all their correspondence when Hitler declared war on America. That this letter somehow survived is miraculous. My father explains in this letter why they should live in America; the chaotic political situation in Germany would make a happy future in that country not feasible for them; maybe later when times would improve they could return to the homeland.

My father sailed to Germany only with the plan to meet her family, get married, and return to America with his bride within six months. He had the tickets for their return together as man and wife in his pocket.

But my father never returned to America. Her family was against the marriage and her consequent leaving with him to a foreign country. It took several years to convince them that he was worthy of her. My parents finally got married in 1934. They settled in the Palatinate and started a family.

In 1940 I was born. I am the fourth child. World War II broke out. When Hitler declared war on America my father said casually in front of his colleagues: “What, this gangster declares war on America? That is just crazy!”

He should have been more careful about whom he talked to. He was reported to his superior and warned that this statement would be enough to send him to Dachau. He was strongly encouraged to enlist as soldier and was destined for the feared Russian Front. Luckily for him, he needed some major dental work done while he was in Prague. It took longer than estimated, and so he was sent to join a unit already stationed in Bavaria.

My father told my siblings and me often of the day the Americans came to Munich. It was the end of April 1945. His unit was positioned upstairs in a school house in Munich. American GI’s already coming up the stairs. My father was ordered by the commanding officer to shoot at them. Instead, my father took his rifle, broke it on the handrail, and threw it at the feet of the German Commander; the latter, in turn, told my father that he would bring him in front of a quick trial and he would be shot after that. My father, who spoke English fluently, told the Americans what had happened. Indeed, they had witnessed it. My father was taken prisoner, along with the others.

My mother, meanwhile was worried because she did not hear anything from my father from April 1945 until January 20, 1946. She did not know if he was alive or dead. And there she was, a young woman of thirty-six, alone with four children. And they were growing and always hungry, and getting enough food was a major problem. The children got sick,and medical help was not always available. There were daily situations of fear and terror and she did not know whom she could trust. She felt terribly alone. She worked all day long and wrote the most beautiful letters at night to my father. He wrote of love and hope, he even wrote a poem for her. She wrote in one letter that he should not write a poem to her again, for she did not believe in the written words anymore. Depression was her daily companion.

Many times my father wrote that he had learned of his release and that he was coming home to her. He was told these lies over and over again. At least he had work in the prison camp, baking bread for everyone, and often had rolls and breads under his overall when returning from the camp bakery to his hungry comrades. He wrote of living in a tent equipped with a stove, but often there was no firewood to use. He wrote of days that were good, when wine and cheese were given to the prisoners. They wondered about it. They thought this would mean they would go home. My father was allowed to read German newspapers, so he knew what was going on in the destroyed homeland. Needless to say, he worried about his wife and children all the time.

The letters my parents exchanged were all censured, of course, and many were not forwarded at all and probably simply ended up in a waste paper basket. Once my mother received a letter that looked like it had been crumpled up. It was a letter that contained totally harmless information.

The last letter in this collection from my father to my mother is dated December 17, 1947. He again states that he is coming home for Christmas, but again, that did not happen; it is possible transportation out of the camp was not well-organized or plans simply had been changed.

My father was finally released from French captivity in late January 1948, and it was I, the youngest child then, who opened the door when he arrived. I was scared when this man declared that he was my father, for he looked so different, certainly not like the man in the photo my mother had on her nightstand. I told him that he could not possibly be my father, because I knew what my father looked like. He insisted that I call my mother. She came, very reluctantly, and looked at this stranger, and with a cry they fell into each other.

My father had come home.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.