Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Blurred Lines»

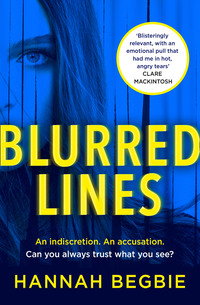

BLURRED LINES

Hannah Begbie

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © Hannah Begbie 2020

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover photograph © Shuttershock.com

Hannah Begbie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008283261

Ebook Edition © July 2020 ISBN: 9780008283278

Version: 2020-08-13

Praise for Hannah Begbie:

‘Compelling, fierce and all too believable … a heart-stopping portrayal of what it costs to speak out’

Clare Empson, author of Him

‘Deeply compelling and gripping, with characters so realistic you feel as if you know them, I couldn’t put it down’

Isy Suttie

‘A fast-paced, tightly-wound thriller with great dialogue and compelling characters. A brilliant page-turner perfectly designed for the #MeToo era’

Viv Groskop

‘Beautifully written, very timely, very honest – I read it deep into the night’

Emma Freud

‘Important and perfectly paced, this is one of the best books I’ve read this year’

Zoe West

Dedication

For my sons, Jack and Griffin

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Hannah Begbie

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Hannah Begbie

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

She feels the sales assistant looking her over, appraising her against the wine that she has delivered to the counter. It is a Burgundy, priced at sixty-five pounds, its provenance declared in elegant loops on a simple label. She couldn’t pronounce this château, and she suspects this man knows that perfectly well. Look at this woman, with her dull, errant hair and the catalogue-bought black trousers that reach for but never quite achieve a tailored fit: at how her slouch and the crease to her brow clash against the pin-straight, darkly varnished floorboards of this wine shop.

He wraps the bottle in crisp crepe paper, one finger cocked like he is taking an elegant tea, as if to tell her: this is how it is done. Granted, her wardrobe, her hairstyle, her whole life cannot be salvaged by a moment of his time, but perhaps the act of witnessing his precision and professionalism and his good taste might, in some small way, chip away at her roughness.

She has pulled this bottle from the shelf because a hand-written card describes it as ‘a classic example of the type’. Now she wishes that she had been bolder. That she had chosen something without a ready-made approval, to state firmly that she knows better than this man, than any man, how her desires are best met by grapes, and terroir, and time in the bottle. Imagine asking if they had the same wine but from another year. A better year, or worse. Knowing what the sun or the humidity or the rain had done to that corner of France in that year.

Why should she know? Who is asking her to know these things?

‘Any tips for drinking it?’ she asks, her demeanour easy and friendly, like she’s only really filling a spare minute while he wraps the thing. Like she has no need of his opinion, but chooses to seek it anyway. A generous gesture that allows for him to know more about this bottle than simply how to wrap it.

‘Are you drinking it straight away?’

She shrugs. She won’t be drinking it at all, unless she’s asked to share it. And even then, she’d only take a few sips.

‘Well don’t let it get too warm,’ he says. ‘Won’t hurt to decant it, but it won’t struggle straight out of the bottle either. Cash or card?’

Becky hands over her debit card. It is the same colour as when she was at school. The first-savings-account hue of somebody who agonizes over whether sixty-five pounds, which she really cannot afford, is enough to spend on wine for a man who might consider it midweek drinking, a bottle to open mindlessly before rushing off to a weekend away, leaving it to idle and spoil on the kitchen island. Is it enough, a bottle like this, for a man like Matthew?

Matthew pays her pretty well. She can’t complain. She knows there are others who make less and are worth far more.

Stop it, she tells herself. You are good at your job. You are.

‘Enjoy it!’ says the man behind the counter as he hands her the bag. Did he see the dismay in her eyes as the card receipt chattered through? Surely he knows that this is a gift, one meant to impress; a wine that she does not understand, intended for someone whose world she only fleetingly visits.

And yet, his smile seems sincere. Perhaps he is honestly grateful for her custom, even if the wine is wasted on her. The money is real enough.

Matthew taught her that, like so much else about their business: everything is only talk, only a possibility, until somebody writes you a cheque, or cashes one you’ve written them.

As she exits the shop she holds her head high. Today is a good day. She has come to West London to deliver a gift and the gift has been well-chosen. It will suffice.

Becky passes the wedding-cake white houses of Portobello, takes in the scent of freshly cut stems from an elegant pink-and-orange-painted boutique floristry and the steam-whistle of a barista’s coffee machine through lacquered café doors flung wide-open. The weather has finally turned a corner. Her skin actually feels warm for the first time in months and she cannot help but stop for a moment, right there on the street corner, and turn her face to the sun, smiling even as she hopes that no one catches her in the act.

It’s a small miracle, she thinks, how an idea can turn into a series of meetings, and then a screenwriter’s draft, and now – or at least soon – will become actors and cameras and lights, and conversations in the edit suite. Like watching a foetus growing across a series of ultrasound images.

Tomorrow her yellow brick road takes her to the Cannes Film Festival where she will meet the people who can really make it happen. Those who can write cheques, or accept them. Her small idea, gathering supporters, players, financiers.

‘We could be shooting this time next year,’ Matthew had said at that very first meeting, within a minute of her giving him her seedling of an idea. ‘Produce it. I’ll back you.’

‘But I don’t know how,’ she’d said, hating herself for confessing her weakness so quickly.

‘Nobody does, the first time.’

And with that statement, he’d made it real.

She steps over the cracks in the pavement. She doesn’t want to jinx it, not now. Not when everything is so close.

She can see Matthew’s terraced stucco villa in the distance, its pilasters and columns all whiter than white against the leafy green health of the pavement trees. The early evening sun reminds her so much of that party night, when she walked this road, on that occasion without wine but with a Jiffy bag of contracts from the office for him to sign, not expecting to leave with a plan for her future.

‘Stay,’ he’d said to her as he signed the last of the Post-it-marked pages. ‘Come and meet some people.’

She’d been the one to order the canapés and the watermelon martini ingredients for this party, and now she was invited to share in them. To accept them as easy gifts from the waiting staff who circulated in crisp white shirts and black trousers.

Of course she should network. Wasn’t that how the world worked? A pretty assistant, charming her way around a beautiful garden, making a name for herself, evading both men’s hands and the scrutiny of their wives’ tracking gazes.

And yet, despite the fact of her canary-yellow dress candy-striped with orange, and the fact that she’d washed her hair that morning with a shampoo that promised gloss and hold, her head itched and she felt out of step and out of place. Here, the rich looked rich, and the nonconformists wore their asymmetric fringes with confidence. In one corner, a famous actor in shredded jeans and Debbie Harry T-shirt made conversation with an elderly critic turned out in linen suit and white Panama hat and both seemed entirely at ease. Where were the people stuck in between? Uncomfortably halfway to somewhere? Unfinished, barely done with being utter imposters?

She had been relieved when Matthew had interrupted a conversation between her and a grey-haired, mildly known actor – not so much a conversation, really, as a lecture – by asking her to step away with him, into his study. She had felt eyes on them as they vanished back into the house together. There was always that question, for some people, concerning what a man and a woman stepping away together might mean, especially when she was his, an employee, and just about still young, and unquestionably ambitious. Despite Matthew’s wife and children being there. Despite the way he kissed his wife readily and easily. Of course somebody would make a sly comment, win a cruel quick laugh. Why else go to a party like this?

The walls of Matthew’s study were tessellated with black-and-white photographs of his beautiful family playing cricket on a beach in Cornwall. Smooth custom-made oak shelves held his BAFTAs and BIFAs and Oscars and a galaxy of other awards in glass, bronze, Perspex, silver and wood.

‘I’ve got the Universal contracts here as well,’ he said. ‘Won’t be a minute.’ He glanced up from the paperwork and caught her looking at his statuettes.

‘Pick one up, if you like? The Academy one’s pretty heavy,’ he said. ‘You don’t want that kind of thing to take you by surprise on the night.’ And then he laughed and she really wasn’t sure whether he was mocking her or if he was expressing some kind of belief in her and so she chose, for once, to try to believe the latter. And as a small, rare bubble of confidence grew in her, no doubt lubricated by three glasses of good champagne, she had told him, ‘I’m ready, I want to make a film. And I have an idea.’

Approaching his house a year later she still marvels at that moment. How did she do it? It had been like pitching to God, but at least prayers go unanswered. No voice from above outright tells you, No. You’re at least allowed to keep your hope. Her heart was in her mouth, she feels sick just remembering it, thrumming its beats through her, telling her to be ready for anything – so afraid was she that Matthew would declare how bad her idea, how shameless her decision to pitch now: at a party, of all times! Becky had fought every natural instinct in her body to flee, and pressed on, talking to her boss, this movie producer whose life was stuffed to the gills with box office smashes and blockbuster hits. He had listened to her talk about the Greek tragedy ‘Medea’ and how it might be remade to speak to modern women, and he had said yes, and then told her to make it for £4 to 5 million, give or take a million for their lead actress who would do it for the prizes, not the payday.

‘It’s about revenge,’ she had told him excitedly, not realizing that you can stop once somebody has said yes. ‘Medea sacrifices everything to help Jason achieve his goals. Then, when he’s taken all she has to offer, he gets bored and leaves her for another woman. And so Medea gets angry.’

As she spoke, something scalding had coursed through her, with the rush of a furiously filling lock. It didn’t take much to connect with this feeling, not really, it was close to the surface wherever she was. ‘He believes a woman’s anger isn’t ever something to worry about,’ she said, ‘but he underestimates her. Medea takes her revenge.’

It didn’t matter that Matthew would never know what had lit that touchpaper inside her. She could see from his half-smile that he was interested in her, and proud of her, and she was already addicted to that feeling.

Becky steps into the road to cross it and a car swerves to avoid her, blaring its horn. Its headlights catch her shins. She steps back, a stomach-twisting jolt of adrenaline waking her up.

On the opposite side of the road an old woman takes pleasure in shaking her head at Becky’s near-fatal mistake as a new story sweeps away red carpets and lofted award statuettes: Becky, mother of one, a development assistant with no produced credits, dead in the road. A head full of dreams, but not enough blood left in her veins to keep them there.

It is an old feeling for Becky, the idea that her waking life might be parted from her body. That her body is sometimes simply a place where things happen, sometimes with her, sometimes without.

These are not helpful thoughts.

She feels small and foolish now. She is a woman without real power. A woman who can barely cross a road. She has the favour of a powerful man, and that is all. For all the cocktails and glamorous lunches, it hasn’t happened yet, the film hasn’t taken off, hasn’t been made. It’s all just words and expressions of interest. Who on earth does she think she is?

She crosses, safely now, passing the old woman who wants desperately to catch Becky’s eye.

Smaller and weaker, she arrives at the side entrance to Matthew’s house, electing to take a route she has taken a dozen times before, stepping down a flight of double-height steps to a wooden door, barbed wire all curled at the top like a helix of DNA. The air smells of fresh creosote and good maintenance and charred meat and through a small side window she can see that lights are on deeper inside the house.

She pushes at the door and it opens easily. Why doesn’t he worry about crime? All that barbed wire and the door still unlocked; a contradiction, a statement, a dare. People seem to come and go here, drifting into Matthew’s home like it’s an exclusive private members’ club. If you turn up and they’re having a family meal, a place is set for you straight away – no trouble, no problem. Becky has eaten like that on half a dozen occasions, smiling along with every family joke until her jaw ached with tension.

She pads over a paved area and pushes at another door into the house, stepping through the dark utility room, rehearsing her lines. No, she can’t stay. It’s a small thank you for Cannes, a token really. If she stays for a drink, will she be so bold as to propose a toast to their forthcoming trip? Is that hopelessly gauche, wishing aloud for success that Matthew has no need of? Siobhan’s laser-guided words hit her again: this is a very expensive kind of work experience. Said to her face, to Siobhan’s credit, as Siobhan booked two hotel rooms and two sets of flights. Chosen and not chosen. Emboldened by Becky’s example, Siobhan is developing her own idea to pitch to Matthew, while also printing up the Cannes travel itineraries.

There is music playing in the kitchen. The lights are on in the hallway, but not in here, where the downlighters are set to low. Becky pauses on the threshold of the room. What if he is home alone? What if he has fallen asleep and now she’ll wake him? She regrets not ringing the front doorbell but Matthew is always at pains to say it’s only ever the builders and delivery men who do that, and she’s more than that to him. Isn’t she?

But this is an imposition. What if she walks in on him getting undressed or even, God help her, masturbating? In the kitchen? she asks herself. Surely not.

She steps over the threshold into a room that is kitchen and dining room and living room all in one, and each area is generously apportioned. The overall footprint is larger than her entire flat.

The retractable glass wall is closed to the garden but its formal raised beds are tastefully under-lit. The kitchen features navy walls and a distressed copper breakfast bar with matching taps. Soap in big blue apothecary bottles and stripped, white-painted floorboards. There are half-full wine glasses on the marble worktop.

Becky sets her own wine down on the kitchen island and looks around for paper with which to leave a note. ‘Popped in?’ ‘Sorry I missed you?’ Or is she right that it’s an imposition, this stealing into a person’s home, even if it’s allowed, encouraged even?

As the music changes track, in the silence between beats, she thinks she hears something – a breath, or a moan, something like pain perhaps. She can’t put a name to it, but her mouth dries and her skin prickles, the fine hairs on her forearms rising.

She wants to flee, but what if it’s him, dying? An olive caught in the throat. An allergy he hasn’t told her about (not that, she’d know). And in the end, she has to check. Of course she does.

She pads quietly around the wood-burning fireplace that part divides the room. Another noise – this time male and urgent. And, horrified, Becky realizes that she is in proximity to sex.

There is movement. On the floor, on the rug that softens the sofa grouping, their bodies mostly hidden by the furniture. Becky cranes her neck a little. She sees a woman’s head, and Matthew on top of her, and the woman is not his wife, cannot be unless Antonia has gone blonde. She notices a tall-heeled foot, black shoe with a red sole, sliding off the rug, onto the flagstone, like a calf’s leg slipping outward as it takes a first step.

The woman says something to the man. Her arm goes up – pushing him or reaching for him? He catches her by the wrist and moves that arm back onto the rug – and his breathing, his grunting, deepens. The woman’s face contorts. Perhaps close to orgasm. Perhaps uncomfortable.

The woman turns her head and looks straight at Becky. And opens her mouth, as if about to speak – or call out – or warn him – or—

Chapter 2

That night in bed, restless under her covers, Becky goes from hot to cold, aggravated by the duvet’s shortness, its longness and finally its mere existence. Window up, window down, she cannot seem to find a simple point of balance between sweating and shivering. She lies on her front, her back, curled up, stretched out, grasping and un-grasping her wrist.

Matthew Kingsman. Oxford man. Family man. Film man. There is a waterlogged feeling in her. Perhaps it is disappointment, though that would be irrational. Matthew is a free agent in a free country. He can do as he pleases, and it is no business of hers.

She tells herself she has been naïve: that people do this all the time. Flings, dalliances, affairs, trust-bending, trust-breaking. There are of course open marriages whose openness isn’t advertised to one and all. People have sex with people they shouldn’t, all the time, particularly in her industry where everyone is looking at themselves, and if not at themselves then at each other, in the mirror or through a camera or on screen. Bodies attractive enough to sell tickets win easy lays, quick fucks, promotions. She gets it. It shouldn’t be news to her. She needs to loosen the fuck up.

Successful people are boundary-benders, boundary-breakers, and maybe it is Becky who should be taking a lesson from this rather than sitting here in judgement. She has so much to learn. She aches under the weight of it, aches at how childish she still is.

All these thoughts ricochet off the sides of her, like a ball in a pinball machine.

She considers for the hundredth time how, with the kitchen lights behind her, she must only have been a silhouette. How she turned and ran so quickly and quietly that perhaps if they were drunk she’ll be remembered as something that couldn’t have happened. A shadow in the corner of the eye, with nothing there on second glance. She was never there. If he asked – and why would he ever ask? – she would look blankly back and deny everything.

It is none of her business how two people have sex. Some people like to dress up. Some people play rough, hold each other down and tie each other up by the wrists, silence and hurt each other. She knows all that. She’s not completely naïve.

At five in the morning, and with just two hours left before it’s time to wake Maisie for school, Becky admits defeat and leaves her bed, padding quietly to the kitchen to make a pot of coffee. Maisie will sleep through the kettle whistle, through the smell of coffee, through all of it. Maisie rarely dreams. She sleeps like a child whose days are straightforward, which is precisely how Becky has laboured to arrange them.

Becky breathes in her home and the smell of washing powder and the ghost of last night’s chilli and tries to calm the thud-crack in her heart. She looks around her small kitchen and at all the boundaries that surround her in her old East London maisonette; at the low ceilings and narrow rooms, at the double-glazed, triple-locked door that leads out onto a paved patio. At the window grills that slide across and meet in the middle. At the moose-headed coat hook in the hallway that holds her black lycra running top and the pair of creased and dusty wide-legged trousers she’d once worn for weekly self-defence classes at the local gym.

At first, what she learnt there made her feel safer than any triple-locked door. She enjoyed making a fist in a boxing glove so her wrists didn’t snap and her tendons didn’t bruise, and how to deliver a punch with speed and precision. She had felt reassured and emboldened by the tight wrap of the gloves around her wrists and how they made her arms feel bionic, almost not her own. She had enjoyed the feeling of strength return to her body.

But she abandoned the lessons when she began using her new-found skills in unconstructive ways. There wasn’t a local gym class on earth that would teach her the skills she needed to defend her against herself.

Becky tries not to panic about how much she has to do, how she will manage a day’s work, a flight to Cannes and a couple more hours’ peppiness for all those new people who will need impressing. All on no sleep whatsoever? Back in her bedroom she lightly folds a dress and rolls up a cotton shirt and two T-shirts. Fills her washbag. Pulls out pants and socks and assembles it all in a pleasing jigsaw inside her carry-on suitcase: two carbon-scented copies of the Medea script at its base.

She makes notes on her Cannes meetings, banishing thoughts of that silken hair spilling out onto the kitchen floor, coming up with six ways to pitch her idea to six different kinds of people.

But she knows what she really wants to do and she knows that it is destructive so she fights it, at first holding her own hand lightly, reassuringly, like a friend. And then when the feeling does not subside, gripping her hand tightly, before grasping at the thin skin and raised veins of her own wrist, holding it tight, as if pulling herself back from a fight. She has agreed, in therapy, that standing up to this instinct is a good thing. Succeeding means she has taken her power back, or something like that; but without sleep all those rules are dissolving at their margins, her desires pushing away old decisions.

Surely if she just does more, the instinct will leave? She clears the washing basket. Cleans surfaces that already gleam. Lays out an array of jams and breakfast cereals despite the fact she never eats breakfast and her daughter’s favourites are firmly established and unflinching.

She means to make a cup of tea next, but somehow before the kettle boils she has opened Scott’s Twitter page and she is already on her way to losing the fight.

Becky has two Twitter accounts: one that is her. And one that isn’t.

The one that isn’t Becky is Melanie. Melanie has a line drawing of a face in the photo caption, all thick and twisty like the pen hasn’t been taken off the page. ‘Melanie Hasn’t Tweeted Yet’ but Melanie follows a few people – thirty-seven corporate accounts like BBC News, Sky News, Popbitch, and another dozen or so famous people, including a TV presenter who crossed the Gobi Desert on foot and whose dinner-party speciality is puffer fish. Then there are forty or so ‘ordinary people’, people who maybe said something funny once or do something unusual or are vocally for or against some issue or other. And she doesn’t check on anything they have to say, because all of them – the corporations, the celebrities, the nobodies – are padding to disguise the fact that Melanie is following Scott.

She knows it’s overkill, but Becky dreads the slip of a fingertip, an accidental ‘like’ or retweet of a Scott comment, anything that might tip him off that Becky Shawcross is monitoring him. Safer not to look directly at him.

Scott has changed his main picture again.

Now Scott is in fancy dress, dressed as Elvis in a maroon button-down shirt, the collar of a leather jacket pulled high around his neck and his hair styled like a whip of black treacle.

It’s not a picture she has seen before.

Perhaps he has been to a party.

She logs into Facebook, via another fake profile account. He friended her without asking questions. He already had 762 friends. Why not welcome another one? Somebody has tagged him at this party. Elvis lives! A grinning friend of his has slung an arm around Scott’s neck. Scott is pouting for the camera in aviators. Not for the first time, he has chosen a costume that allows him to wear sunglasses. He likes to hide his eyes, those giveaway windows to the soul.

She scrolls back through his timeline. She’s seen it all before, a thousand times. His whole life is in her head, or at least those parts that she can get at from the safety of her own flat.

Last year Scott purchased a large indoor fish tank. His colleagues appreciated the cupcakes he bought them one afternoon in Soho. He celebrated the birthday of his oldest house plant and 152 people put hearts by it.

Recently drank espresso Martinis with an old friend who’d flown over from Australia. You’d think he was Australian, with a name like Scott, but he’s English. Like Becky, he was brought up in Hounslow, where the roof tiles vibrate under the flight paths.

And there’s one picture of him that kills her every time now. Taken a year or so ago, it’s like he’s staring right back at her, without the usual sunglasses hiding his eyes, without a care in the world. Without remorse. You don’t get that icy-blue finish to the eyes without going into a shop and buying coloured contact lenses, without swaggering in there, your veins running cold with vanity. In the picture, he’s got an expensive haircut with bits of white blond at the ends. Becky reckons the colour is officially ‘ash blond’. Successful, good-looking, like a boy band member, his hair dipped in ash dye – the ashes of other people. Not a crack in that gorgeous fucking life of his.

She surrenders to it, the scanning and watching distracts her from her twitching hands, from thoughts of the kitchen floor. She’ll read him until Maisie stirs, she knows that now, so she scrolls to champagne glasses intertwined and fizzing. She surfs his flat, job, and the people who love him best (a sister in Belgium, some nieces and nephews). No sign of a significant other; that’s something, at least.

How easily he lives.

But she is breathing quickly now, the energy inside whipping itself into a hot storm with nowhere to go because it’s not enough to see him live his life. It never is. And yet, she has a daughter who relies on her. Everything she wants must be measured against that.

Enough, she tells herself. And so she dresses in jogging bottoms and threads the laces of her running shoes with trembling hands and closes the door behind her with a double then a triple lock. Silently, so as not to wake Maisie, a crackle of worry across her chest about leaving her, but knowing that there are two people to look after. Another edict from another therapist. Self-care. Making time for her.

Becky takes three quick steps, ordering everything inside herself to be quiet, and soon enough she has slipped into a good, quick pace and is running through the streets, heels slamming hard on concrete, landing so as to feel those shockwaves snake up sharp through fibula and tibia. And then, when her chest and muscles ache, she adjusts her gait to save her shin-splints and instead let lungs and thighs scream.