Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Erdogan Rising»

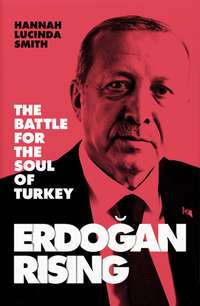

ERDOĞAN RISING

The Battle for the Soul of Turkey

Hannah Lucinda Smith

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Hannah Lucinda Smith 2019

Cover image © Getty Images/Bloomberg/Contributor

Hannah Lucinda Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008308841

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008308865

Version: 2019-08-26

Dedication

For my dad, who planted so many seeds

Epigraph

Yet the school of Turkish politics was so ignoble that not even the best could graduate from it unaffected.

T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

Cast of Characters

Acronyms

Timeline

Introduction

1 Two Turkeys, Two Tribes

2 Syria: The Backstory

3 Building Brand Erdoğan

4 Erdoğan and Friends

5 Syria: The War Next Door

6 The Exodus

7 The Kurds

8 Peace, Interrupted

9 The Coup

10 Atatürk’s Children

11 Erdoğan’s New Turkey

12 Spin

13 The Misfits

14 The War Leaders

15 Erdoğan’s Endgame

List of Illustrations

Picture Section

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

MAPS

Turkey

Syria and Turkish border region

Refugee smuggling routes from Turkey to Europe

Kurdish region of Turkey, Iraq and Syria

Istanbul

Areas where Turkish army is fighting in northern Syria

CAST OF CHARACTERS

| Clique | |

| Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | president of Turkey, former prime minister and mayor of Istanbul |

| Berat Albayrak | Erdoğan’s son-in-law, current economy minister |

| Hüseyin Besli | Erdoğan’s speechwriter |

| Ahmet Davutoğlu | foreign minister, later Turkish prime minister |

| Necmettin Erbakan | leader of the National Salvation Party, Erdoğan’s first party |

| Abdullah Gül | Erdoğan’s early ally, former president |

| I˙brahim Kalın | Erdoğan’s spokesman |

| Hilâl Kaplan | pro-Erdoğan journalist |

| Erol Olçok | spin doctor |

| Opposition | |

| Mustafa Kemal Atatürk | founder of the Turkish Republic |

| Selahattin Demirtaş | Kurdish political leader |

| Muharrem I˙nce | Erdoğan’s 2018 presidential rival |

| Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu | leader of the opposition |

| Enemies | |

| Fethullah Gülen | Islamist cleric and accused coup plotter |

| Abdullah Öcalan | leader of the PKK, Kurdish militant group |

ACRONYMS

| AKP | Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi: Justice and Development Party, Erdoğan’s group, centre-right Islamist |

| CHP | Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi: Republican People’s Party, Atatürk’s group and main opposition, led by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, left-leaning secularist |

| FSA | Free Syrian Army: mainstream armed opposition to Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad. Originally nationalist, later infiltrated and overtaken by Islamist elements. Supported at various times by Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, US, UK and other European countries |

| HDP | Halkların Demokratik Partisi: People’s Democratic Party, main Kurdish group, led by Selahattin Demirtaş |

| Isis | Islamic State of Iraq and Syria: extreme Islamist group comprised mainly of foreign fighters who travelled into Syria via Turkey. Initially tolerated by the FSA, later turned against them and seized huge tracts of rebel-held Syria |

| JAN | Jabhat al-Nusra: the Support Front, Al-Qaeda’s franchise in Syria. Comprised mainly of Syrian Islamists, largely fought alongside the FSA. Listed as a terror group by the US in December 2012 |

| MSP | Milli Selâmet Partisi: National Salvation Party, main Islamist group in 1970s and Erdoğan’s first party, led by Necmettin Erbakan, anti-Western Islamist. Closed following the 1980 coup |

| PKK | Partiye Karkerên Kurdistanê: Kurdistan Workers’ Party, Kurdish militia founded by Abdullah Öcalan in 1978, fighting insurgency in south-eastern Turkey since 1984. Banned in Turkey, EU and United States |

| RP | Refah Partisi: Welfare Party, Erbakan’s new group and main Islamist party in 1980s and 1990s. Closed following the 1997 coup |

| YPG | Yekîneyên Parastina Gel: People’s Protection Units, Syrian wing of the PKK. Founded in 2004 but rose to prominence during the Syrian conflict. Classed as terror group in Turkey; allied with US in fight against Isis |

TIMELINE

| 1923 | Atatürk founds the Turkish Republic |

| 1938 | Atatürk dies |

| 1950 | Turkey’s first democratic elections |

| 1960 | First coup of the republic |

| 1971 | Second coup of the republic |

| 1980 | Third coup of the republic |

| 1994 | Erdoğan becomes mayor of Istanbul |

| 1997 | ‘Postmodern coup’ brings down Necmettin Erbakan, Turkey’s first Islamist prime minister |

| 1998 | Erdoğan sent to prison for reciting Islamist poem at a rally |

| 2002 | November: AKP voted in for the first time |

| 2003 | March: Erdoğan becomes prime minister |

| 2007 | Abdullah Gül becomes president |

| 2011 | Syrian uprising begins |

| 2013 | March: Turkey begins peace process with the PKKMay/June: Gezi park protests in TurkeyDecember: Corruption scandal rocks the AKP, crackdown on Fethullah Gülen begins |

| 2014 | August: Erdoğan steps down as prime minister and becomes Turkey’s first directly elected president |

| 2015 | Refugee crisis brings more than a million people from Turkey to the European UnionJuly: Turkey–PKK ceasefire collapses |

| 2016 | March: Turkey and EU sign 6 billion euro refugee dealJuly: Rogue generals launch coup attempt against Erdoğan |

| 2017 | April: Erdoğan wins constitutional referendum to change Turkey from parliamentary to presidential system |

| 2018 | June: Erdoğan wins presidential elections, triggering constitutional reforms and installing him in the palace until 2023 |

INTRODUCTION

July 2016

It is less than forty-eight hours since rogue soldiers tried to kill him and here Erdoğan is, back on stage. The sun is setting and the call to prayer is sounding, and the president is wiping a tear from his eye.

‘Erol was an old friend of mine,’ he starts, then breaks. ‘I cannot speak any more. God is great.’

Erol Olçok: Erdoğan’s ad man, his trusted spin doctor, his loyal friend. One of the first to race to the Bosphorus bridge last night, his corpse now before us in a coffin.

Nothing will be as it was before, for Olçok’s family, for Erdoğan, or for Turkey. Two nights ago, as Istanbul’s glitterati sat drinking on the banks of the Bosphorus, tanks filled the bridge and war planes split the skies. The army was revolting against Erdoğan – but soon Erdoğan’s own infantry was on the streets, with Erol Olçok at the first line. Bare-chested young men stood side by side with headscarved women in front of machine-gun fire on this midsummer night; others lay down on tarmac in front of rolling tanks. And as fortunes turned against the putschist generals, Erdoğan’s angry, shirtless, sweaty men removed their belts to whip the coup’s surrendering foot soldiers. Their twisted faces were lit with the perfect aura of an early summer’s morning in Istanbul: a glorious backdrop of dawn over the city that spans two continents. The images flew around social media within minutes. They were beautiful, and they were horrifying.

The coup has been crushed but the toll is huge. Two hundred and sixty-five people have died over the bloody span of this night, more than half of them civilians who came out to resist in Erdoğan’s name. Erol Olçok was shot dead alongside his sixteen-year-old son, Abdullah, as soldiers fired into the protesters on the bridge. Thousands more have been injured. There are still sporadic bursts of fighting as suspected plotters resist arrest; Istanbul’s airspace reverberates with the roar of patrolling F-16 fighter jets. The streets have been hauntingly quiet all weekend, as Turks stay inside, watch the news and pray.

Among the dead: a local mayor shot point blank in the stomach as he tried to speak with the soldiers; the older brother of one of Erdoğan’s aides; a famous columnist with the pro-government newspaper Yeni şafak. A crack team of special forces soldiers had burst into the Mediterranean resort where Erdoğan was holidaying, ready to kill him if necessary and missing him only by minutes.

Erdoğan has already bounced back, his close brush with death seemingly leaving no dent. He has returned to Istanbul, banished the soldiers back to their barracks, and called the coup attempt a ‘gift from God’ that will allow him to finally cleanse the state of those trying to destroy it. Six thousand people have been detained by the time he addresses the thousands-strong crowd at Erol Olçok’s funeral, at a mosque on the Asian side of Istanbul. The imam implores God as he leads the prayers for the slain man and his son: ‘Protect us from the wickedness of the educated!’

A weight is descending on Turkey. Each night Taksim Square fills with huge crowds of Erdoğan’s supporters, turning out to make sure his enemies don’t come back. Within days a state of emergency is declared, and every day thousands more suspected collaborators are arrested. The alleged ringleaders are paraded on state television with black eyes and bandages around their heads.

Privately, friends tell me they are worried. Goodbye to the Republic, writes one by text message. Goodbye to democracy.

The heart of my Istanbul neighbourhood, which usually bustles at all hours with street sellers, taxi drivers and prostitutes, is near-silent the morning after the coup; the pavements empty, the traffic thinned down to a few lonely cars. The only people I bump into as I walk around the deserted streets are the women who always stand on the main thoroughfare on a Saturday, selling black-and-white postcards to the shoppers. Usually they ask for five liras for this low-resolution print of Atatürk, father to the Turkish nation. Today, a middle-aged woman with blonde perm presses one silently into my hand.

‘Man, this is nothing but a country of cults,’ says my friend Yusuf a few days later, dazed and still trying to make sense of what is unfolding. ‘It’s Jerusalem in the Year Zero.’

In the years that have passed since July 2016, as I have filled newspaper column inches with stories of Erdoğan’s swelling crackdown on his opponents, his skewed election wins and questionable wars, I have been asked the same question time and again: ‘Why doesn’t the West just cut Erdoğan off? Make him a pariah, and leave him and Turkey to go their own way?’

The morality is complex but the answer is simple: we can’t turn our backs on Turkey because Turkey and Erdoğan matter. Forget old clichés about East-meets-West – it is far more important than that. Here is a country that buffers Europe on one side, the Middle East on another, and the old Soviet Union on a third – and which absorbs the impacts of chaos and upheaval in each of those regions. During the Soviet era, it took in refugees from the eastern bloc looking to escape the despotism of communism. When that empire collapsed, it became a place where the poor ex-Soviets went for work, and the rich showed up to party. Now, with the Middle East sinking into ever-greater turmoil, it is the world’s biggest refugee-hosting nation, with five million from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and others.

Turkey is a member of the G20, and is recognised as one of the world’s largest economies. It has the second biggest army in NATO, the Western military alliance which, with the rising expansionist ambitions of Russian President Vladimir Putin, is finding itself sucked into a new Cold War. More than six million Turks live abroad, the street ambassadors of a country that trades and negotiates with almost every other nation on earth. This is not a far-off hermit-state, isolated from the rest of the world. It is a major player, vital to global security and prosperity.

For millennia, the ground on which modern Turkey stands has been coveted and fought over because it stands at the nexus of trade routes and civilisations. To see it for yourself, spend an hour people-watching under the soaring ceiling of the new Istanbul airport, the biggest of Erdoğan’s increasingly outlandish vanity construction projects. It was opened in April 2019, and the Turkish government says that more than 200 million people will pass through its halls by the year 2022, making it the biggest and busiest in the world – twice as many passengers as Atlanta Airport, two and a half times as many as Heathrow. Cruise through its duty-free shopping area and you will spot Gulf Arab women wrapped in black fabric with only their eyes showing alongside sunburnt and flustered Brits in ill-advised tank-tops and shorts. There will be dreadlocked backpackers, preened Russian princesses, and, if you time it right, Islamic pilgrims swathed in white sheets making their way to Mecca. There will be people with wide Asiatic faces, and statuesque African women swathed in fabulous prints. Turkey sits at the centre of all of this.

It sits, too, at the centre of the journeys that the people on the wrong side of globalisation are making – the illicit trafficking routes that stretch from the Middle East and Africa, through Turkey and the Aegean Sea to Europe. In Istanbul’s backstreet tea shops another kind of travel market is flourishing, no less buoyant than that in the ticket halls of the new Istanbul airport. Here, shady men in leather jackets cut deadly deals with desperate people. Survival does not come guaranteed with a smuggler’s ticket to Europe, but it will cost you more than a budget flight from the shiny new airport.

So let’s think about what might happen if Erdoğan were to turn Turkey’s back on the West entirely, or if the country were to descend into full-on chaos. That surge of people in 2015, travelling from Turkey’s shores to Greece in search of a new life in Europe? That was nothing. There are millions more in the developing world still desperate to make that journey, and a collapsed Turkey could be their back door. What if, even worse, there were to be a major conflict or economic collapse in Turkey itself? Not only would thousands, perhaps millions, of Turks join the flow to Europe, but shrewd leaders like Russia’s Vladimir Putin would be quick to capitalise on the chaos to expand his territories and influence, just as he has done in Syria.

Erdoğan is no fool. He knows how important he is and he plays on it, often seeming to push his Western allies’ buttons just to see what will happen. He may sometimes look like a man deranged, but he is also a smart political operator who was refining his brand of populism a decade and a half before Donald Trump cottoned on. If Western countries want to contain and control Erdoğan – as they will have to if they are to keep Turkey stable and engaged in the world – then first they need to understand him. More than that, they need to understand why so many Turks adore him.

What is there to adore? On the face of it, not very much. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan lives in a thousand-room palace complex, Aksaray (White Palace), that he built almost immediately on becoming president. He and his followers have a taste for outlandish historical dressing-up. In a photo call with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, he posed on the staircase of Aksaray with soldiers decked out in costumes from the various eras of the Ottoman Empire. Despite his constant harping on about his working-class roots, and his apparent championing of the underdog against the elites, his wife and daughters dress in haute couture from the famous fashion houses of Europe.

The party Erdoğan leads, the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP), is the most successful in Turkey’s democratic history, even though it has never won more than 50 per cent of the vote. Erdoğan himself has stood at the helm of Turkish politics longer than any other leader in the country’s history. Since first becoming prime minister in 2003 he has quashed the power of the military, rewritten the country’s constitution, remoulded its foreign relations and mastered divide-and-rule politics better than any other current world leader.

Erdoğan’s grip on power might often appear shaky – he only just clinches victory each time he takes his country to the ballot box. But it is this constant sense of threat, this dread that he could be ousted and everything go back to the way it was before he came, that galvanises his supporters. He is not an Assad or a Putin, who use their faked and overwhelming electoral victories to cling on in their palaces. Erdoğan’s continuing dominance over Turkey rests as heavily on those who despise him as it does on those who idolise him. In order to be loved more, he must show his fanbase that there are those who are ready to overthrow him – and could feasibly do so. So, too, must they sense the constant threat in order to feel the wave of overwhelming ecstasy when he comes out on top after yet another crisis – and there have been many of those.

Turkey is still officially a candidate for EU membership, yet in my time covering this country as a newspaper correspondent I have been detained by the police twice, tear-gassed more times than I can remember, and had a Turkish tank turn its turret on me as I tried to speak with Syrians fleeing an onslaught of violence behind the closed border. From my front door I have watched the country I call home nosedive down the rankings for democracy, press freedom and human rights. Like every other journalist in Turkey I am constantly reconfiguring the limits of what I can say. Can I laugh? Criticise? Question? The threat of imprisonment or deportation always lingers in the air for the country’s international press corps, but for Turkish journalists it is real. Some sixty-eight are currently behind bars, the highest number of any country in the world. Add to them the tens of thousands of academics, opposition activists, serving politicians and alleged coup plotters who are also languishing in jail, waiting for trials that are likely to take years to come to court, and you start to get a sense of the kind of country Turkey has become – although a tourist searching for a cheap holiday might still look at the weak lira and the turquoise seas and happily bring their family here for a fortnight. While the package-deal masses race to the all-inclusive resorts and adventurous weekenders explore Istanbul’s atmospheric backstreets, Turks are watching their savings crumble, food prices soar and their children frantically search for any way out of the country.

To write – and to live – under Erdoğan’s tightening authoritarianism is to cohabit with a voice in your head that asks Are you sure you want to say that? every time you press send on an article or crack a joke with a stranger. It is to see your tendency for social smoking soar into a daily, furtive habit that you indulge by the window late at night, and then to look in the mirror in the morning and realise that the faint worry line between your eyebrows is setting into a deep crevice. Dictatorship screws with your sex life; it makes you go through an internal checklist on every person you meet – what are they wearing? Where are they from? Who do they work for and how far can I trust them? I hear my neighbours rowing more often these days, witness more fights breaking out on Istanbul’s streets. The Turks who love the way things are going like to rub it in everyone else’s face. The Turks who hate it usually spill everything to the Westerners they meet – some of the few safe sounding boards they have left. Conversations that start with ‘How long have you lived in Turkey?’ usually come round to ‘Why on earth do you still stay?’ The stress of wondering if your phone is tapped and your flat being watched slows down your brain, becomes a tiring distraction, while at some point, you realise that all your conversations with friends come back to politics, and that although there is plenty of material for cynical, satirical humour none of it makes you feel much better once you’re done laughing. To live in this system is to watch people you know be seduced by power and money, and happily throw away their moral compass as they pursue them. It is to suck up to people you despise because in order to survive you have to – and then to start despising yourself.

All of this creeps up on you, and by the time you realise what you are looking at it is already too late. It was only after the coup attempt that I saw clearly what had been happening all along – the descent of Turkey’s shaking democracy into one-man rule, the dawn of the state of Erdoğan. While I was focusing on the minutiae of daily news, on the war in Syria and the refugee crisis in Europe, his dominance had grown so entrenched that he had become inseparable from the state, and the state indivisible from the nation. Now, the answer to the eternal question posed by every journalist in Turkey is that it is fine to laugh and question and criticise – so long as you leave Erdoğan out of it. But in a country so monopolised, that leaves very little room for any discussion at all.

I have seen Turkey and Erdoğan through seven elections, dozens of terror attacks, a coup attempt, a civil war, foreign misadventures, slanging matches with Europe, mass street protests, a refugee influx and a massive purge of the public sector. And each time, when I have thought, this must be it, this will finish him, he has come out on top even stronger.

I have to give it to him – Turkey’s president has handed me some great material. Often, I have wished I could hand it back.

Erdoğan is the original postmodern populist. In power for seventeen years, his latest election win in June 2018 means he will stay until at least 2023. Already there is a generation of Turks who can remember little or nothing before the Erdoğan era, and his detractors have much to worry about. They fret over his creeping Islamisation of Turkey, once the staunchest of secular states. They point to his fierce crackdown on Kurdish rebels in the east of his country, where hundreds of thousands have been killed or displaced, and his cosiness with armed rebel groups of questionable ideology in Syria. Europe, which once saw Erdoğan as its darling, now deals with him increasingly as if he were an obnoxious teenager. The inhabitants of the Greek islands within spitting distance of the Turkish coast hold their collective breath and brace each time he threatens to open his borders to allow hundreds of thousands of migrants to flow across the Aegean in cheap plastic boats.

I have spent six years watching Erdoğan, speaking to his followers, and sniffing the winds. I think about him every day and write about him on most days, even though we have never met. But I never set out to be an Erdoğan-watcher, or even to be a Turkey correspondent.

In early 2013 I moved from London to Antakya, a tiny town on Turkey’s southern border with Syria, to pursue a career as a freelance war correspondent. The war next door had turned Antakya into a busy hive of spooks, arms dealers, refugees and journalists. The Syrian rebels had captured two nearby border crossings from President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, and I spent a year crossing back and forth through them into Syria to report on the spiralling slaughter. But as Syria turned darker and colleagues started to go missing at the hands of criminal gangs and Islamist militias, the journalists dropped away from Antakya. Along with most of the Syria reporter crowd I moved north, to Istanbul, where not so much was happening.

The huge Gezi Park protests, which in the spring of 2013 had briefly morphed from small environmentalist demonstrations into the most serious street opposition Erdoğan had ever faced, had now petered out into leftist forums scattered across Istanbul’s upmarket districts. They were happy protests – anyone could stand on a soapbox and, instead of clapping (too bawdy and overwhelming), the audience would wiggle their raised hands in appreciation. I doubt they caused Erdoğan too much anguish. For a year or so after Gezi, small-scale street demonstrations became the city’s number one participation sport – with protagonists boiled down to a hard core who just seemed to enjoy getting tear-gassed. One student ringleader I interviewed talked about upcoming protests as ‘clashes with the cops’, as if that were the main point of the event. The demonstrations became so common and predictable they were more of a nuisance than news. Several times over the course of that year, tear gas seeped into my bedroom as I tried to sleep.