Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

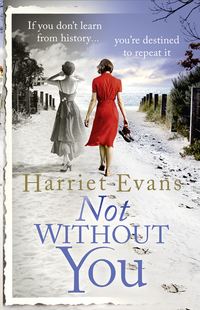

Kitabı oku: «Not Without You», sayfa 2

It’s funny – I never thought Donna and I would lose touch. We stopped hanging out so much when I moved to London for South Street People, then she had a baby. She wasn’t best pleased when I told her I was off to Hollywood. I don’t think she ever really believed I wanted to be an actress. She thought it was all stupid, that Mum was pushing me into it.

‘OK, OK.’ Artie isn’t interested. ‘Take them, read them through if you want. But will you do me a favour?’ He puts his hand on his chest and looks intently at me. ‘Will you read Love Me, Love My Pooch for me? As a personal favour? If you hate it, no problem. Of course!’ He laughs. ‘But I want to see what you think. They’re offering pretty big bucks … I have a feeling about this one. I think it could be your moment. Take you Sandy–Jen big. That’s the dream, OK? And I’m working on it for you.’ He takes his hand off his chest, and gives me the script, solemnly. ‘Now, tell me what picture you’d like to make. Let’s hear it. Let’s make it!’ He claps his hands.

I’m still clutching the pile of scripts, with Love Me, Love My Stupid Pooch on the top. I clear my throat, nervously.

‘I want to … This is going to sound stupid, OK? So bear with me. You know I moved house last year?’

‘Sure do, honey. I found you the contractors, didn’t I?’

‘Of course.’ Artie knows everyone useful in this town. ‘You know why I bought that house?’

‘This is easy. Because you needed a fuck-off huge place means you can tell the world you’re a big star. “Look at me! Screw you!”’ Artie chuckles.

‘Well, sure,’ I say, though actually I don’t care about that stuff that much the way some people do. I’ve got a lot of money, I give some of it away and I take care of the rest, I don’t need to go nuts and start buying yachts and private islands. This was the place I always wanted. It’s a beautiful thirties house, long, low, L-shaped, high up in the hills, kind of English meets Mediterranean, simple and well built. Blue shutters, jasmine crawling over the walls, Art Deco French doors leading out to a scallop-shaped pool.

I love it, but it has a special connection that means I love it even more.

‘I bought the house because it belonged to Eve Noel. She lived there after her marriage.’

Artie’s lying back against the couch. He scrunches up his face. ‘Who? The … the movie star? The crazy one?’

‘She wasn’t crazy.’

Artie scratches his stomach. ‘Well, she disappeared. She was huge, then she vanished. I heard she was crazy. Or dead. Didn’t she die?’

‘She disappeared,’ I say. ‘She’s still alive. I mean, she must be somewhere. But no one knows where. She made those seven amazing films, she was the biggest star in the world for five years or so, and then she vanished.’

‘OK, so what?’ Artie puts his hands behind his head.

‘I want to make a film about her.’

From my bag I pull out a battered copy of Eve Noel and the Myth of Hollywood, the frustratingly slim biography of her that ends in 1961. I must have read it about twenty times. ‘So … it’d be a film about where she came from, about her starting out in Hollywood, what happened to her, why she left.’

‘I never knew you were into Eve Noel. Old movies.’ Artie makes it sound like I’ve told him I love anal porn.

‘Sure,’ I say. ‘My whole childhood was spent on the sofa watching videos. It’s a wonder I don’t have rickets – I never saw the sun.’

Artie grunts. He doesn’t much like funny women. ‘So why the big obsession with her?’

‘She’s the best. The last real Hollywood star. And she … She grew up near me, a little village near Gloucester?’ I can hear the edge of the West Country accent creep into my voice, and I stutter to correct it. ‘It’s crazy, no one knows what happened to her, why she left LA.’

The first time I saw A Girl Named Rose, I was ten. I remember we had a new three-piece suite. It was squeaky, because Mum didn’t want to take off the plastic covers in case it spoiled. I was ill with flu that knocked me out for a week and I lay on the sofa under an old blanket and watched A Girl Named Rose, and it changed my life. I never thought about being an actress before then, even though Mum had been one, or tried to, before I was born, but after I saw that film it was all I wanted to do. Not the kind Mum wanted me to be, with patent-leather shoes and bunches, a cute smile, parroting lines to TV directors, but the kind that did what Eve Noel did. I’d sit on the sofa while Mum talked on the phone or had her friends over, and Dad worked in the garage – first the one garage, then two, then five, so we could afford holidays in Majorca, a new car for Mum, a bigger house, drama school for me. The world would go on around me and I’d be there, watching Mary Poppins and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, anything with Elizabeth Taylor, all the old musicals, Some Like It Hot … you name it, but always coming back to Eve Noel, A Girl Named Rose, Helen of Troy, The Boy Next Door. I even cut out pictures of my favourite films and made a montage in my room: Julie Andrews running across the fields; Vivien Leigh standing outside Tara; Audrey Hepburn whizzing through Rome with Gregory Peck; Eve Noel walking down the road smiling, hands in the pockets of her flared skirt.

Everyone else at school thought I was weird. It was weird, probably. But Eve Noel and that film opened a world up for me. It seemed magical. It isn’t, any more, and I should know. Back then it was all about glamour and artifice, these gods and goddesses deigning to appear on a screen for us. Whereas I know what it’s like now. It’s a business, less profitable than online poker, but a profitable business still, until the Internet kills it totally dead.

Mum and I used to drive past Eve Noel’s old house. It’s in ruins now. It’s funny – everyone knows that’s where a film star grew up. But no one knows the film star any more, or even where she is now. Her last picture was Triumph and Tragedy, in 1961, and it was a big flop. There’s a picture of her at the Oscars, the year she didn’t win and her husband did. She’s smiling, so lovely, but she doesn’t look right. Her eyes are odd, I can’t describe it. And then – nothing.

I try and explain all this to Artie. He nods enthusiastically. ‘Give me the pitch then,’ he says.

‘The pitch?’

He’s grinning. ‘Come on, Sophie. You know it’s you, but you’re gonna have to get some big guys to put big money up if you want this thing made. Give me the one-line pitch.’

‘Oh …’ I clear my throat. ‘Kind of … A Star is Born meets … um … Rebecca? Because the house burns down. I suppose maybe it’s more The Player set in the fifties meets A Star is Born, or—’

‘Boorrring!!’ Artie buzzes. My head snaps up – I’m astonished.

‘Listen,’ he says. ‘You are my number one client. You are so important to me. This could be amazing. I’m talking Oscar-amazing. But it could be career suicide. Again. And you can’t afford that. Again.’

He stands up again and pats his stomach. ‘I’m a pig. I’m a pig! Listen to me, sweetheart. Go home. Think up a great pitch. We have to get this thing made.’

‘Really?’ I stand up, stumbling slightly.

‘Really. But you’re totally right. If we can’t do it properly we should forget all about it.’

‘That’s not—’

‘And you’ll read the dog script? For me? Think about who’d be good, who you’d like to work with?’ I must have nodded, because he gives a big smile. ‘Thank you so much. Take the other scripts. Read them. I wanna know what you think of them all. I’m interested in your opinion. Sophie Leigh Brand Expansion. We’re big, we need to go bigger, and you’re the one who’s gonna lead us there. Capisce?’

‘Thanks, Artie,’ I say, aware that something is slipping from my grasp but unsure of how to take it back. ‘But also the Eve Noel project, let’s think—’

‘Sure, sure!’ He pats me on the back and squeezes my shoulder. ‘I think with the right project and a good writer we could have something wonderful. And listen, I spoke to Tommy, did he tell you?’ I shake my head. Tommy’s my manager, and he rings Artie roughly ten times a day with ideas, most of which Artie rejects. ‘It’s fantastic news!’

‘What?’

‘He tested the line we discussed for the Up! Kidz Challenge Awards on a focus group and it came back great. So that’s what you’re saying. OK? Wanna give it a try, for old times’ sake?’

I smile obligingly, hold up my bare left hand, then scream, ‘I LOST MY RING!!!’

This is the line I’m famous for, from The Bride and Groom. It’s a cute film actually, about a wedding from the girl’s point of view: bitchy bridesmaids, rows with parents – and from the guy’s point of view: problems at work, a bachelor party that ends in disaster. The bride, Jenny, loses her ring halfway through in a cake shop, and that’s what she screams. I don’t say it often, because I don’t want to have a catchphrase. Tommy would sell dolls that scream ‘I LOST MY RING’ and T-shirts by the dozen if I let him. I don’t let him.

‘Wonderful. Just wonderful.’ Artie’s clutching his heart. I push my sunglasses back down over my eyes.

‘It’s good to see you,’ I say, hugging him. ‘We’ll talk soon. When are the awards?’

‘Two weeks. Ashley will brief you. So you’re OK? You know you’re going with Patrick, yes?’

I hesitate. ‘Well, and George,’ I say. ‘A bonding night out before we start shooting.’

‘George? OK.’

I match him stare for stare and as I look at him I realise he knows.

‘George is a great director.’ For once Artie’s not smiling. His tanned face droops, like a hound dog. His beady eyes rake over me.

‘I know he is,’ I say slowly.

‘That’s all.’ He turns away. ‘That’s all I’m gonna say. OK?’

I can imagine what’s going on in his mind. If she’s banging George, they’ll be making trouble on set. Patrick Drew’s gonna get difficult about his close-ups as it’ll all be on her. George’ll dump her halfway through and start fucking someone else and she’ll go schizoid. This is a disaster.

I know it’s nothing serious, me and George. He’s A-list, so am I; we won’t squeal on each other. He’s way older than I am, he’s been around. Plus I don’t need a relationship at the moment, neither does he. If we screw each other once a week, what’s the harm?

Artie chews something at the back of his mouth, rapidly, for a few seconds, then claps his hands. ‘OK, we’ll regroup afterwards about your Eve Noel idea. I like it, you know. If not for you then someone. Maybe you’re right! Could be big …’ He pauses. ‘Hey, you should be a producer.’

He laughs, and I laugh, then I wonder why I’m laughing. Me, in a suit, putting the finance on a movie together, all of that. Then I think … no. That’s not for me, I couldn’t do that. I’m too used to being the star – it’s true isn’t it?

‘Read the scripts, think it over,’ he says, as I leave the room. ‘Then we’ll talk.’

CHAPTER THREE

AS I EXIT the building, I’m still thinking about Darren Weller and the day we went to Stratford, me and Donna escaping to McDonald’s. I’m smiling at the randomness of this memory, walking through the glass lobby of WAM, clutching this bunch of scripts, and suddenly—

‘Ow!’ Someone’s bumped into me. ‘Fuck,’ I say, rubbing my boob awkwardly and trying to hold onto the scripts, because she got me with her elbow and it is painful.

This girl grips my arm. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she says, her eyes huge. ‘Oh, my gosh, that was totally my fault. Are you OK—?’ She looks at me and laughs. ‘Oh, no! That’s so weird. Sophie! Hi! I didn’t recognise you with your shades on.’

I’m trying not to rub my boob in public. I can see T.J. waiting by the car right outside. ‘Hi there,’ I smile. ‘Have a great day!’

‘You don’t remember me, do you?’

I stare at her. Who the hell is she? ‘No, I’m sorry,’ I say, beaming my big megawatt smile and going into crazy-person exit-strategy mode. ‘But, it’s great to meet you, so—’ She’s still grinning, although she looks nervous, and something about her eyes, her smile, I don’t know, it’s familiar. ‘Oh, my God, of course,’ I say impulsively. I push my sunglasses up onto my head. ‘It’s …’

I search my memory, but it’s blank. The weird thing is, she looks like me.

‘Sara?’ she says hesitantly. ‘Sara Cain. From Jimmy Samba’s.’ She’s still smiling. ‘It’s been so long. It’s really fine.’

I stare at her, and the memory leads me back, illuminating the way, as scenes light up in my mind from that messy, golden summer.

‘Sara Cain,’ I say. ‘Oh, my gosh.’

Back in 2004 I starred in a sweet British romcom, I Do I Do, during a break in South Street People’s shooting schedule. It did really well, better than we all expected, and LA casting agents started asking to see me, so I went out to Hollywood again the following summer. That was when Donna and I kind of fell out, actually; she told me it was a big mistake and I was in over my head.

She was wrong, as it turns out. It was a great time. I was young, didn’t have anything to lose, and I thought it was pretty crazy that I was there anyway, to be honest. Jimmy Samba’s was the frozen-yoghurt place on Venice Beach where my roommate Maritza worked and we all practically lived there: a whole gang of us, actors, writers, models, musicians, all waiting for that big break.

‘Your twin, remember?’ I stare at her intently. She gives a small, self-conscious giggle.

‘Wow,’ I say. ‘The twins. Sara, I’m so sorry, of course I remember you.’

The thing about her was, we had a few auditions together, and every time people always commented on how similar we looked. She had a couple of pilots, and the last time I saw her it looked like things might be about to happen for her.

The sight of her is like hearing ‘Hollaback Girl’ – that was my song of that summer. Takes you totally back there to a time that I rarely think about now. It’s gone and that’s weird, because we were friends. Her dad was a plastic surgeon, I remember that now, an old guy who’d done all the stars; I loved hearing her stories about him. She even came up to the rental house in Los Feliz, her and some of the gang, after I moved out of Venice. But it was an uncomfortable evening. Sara especially was weird. And even though I called her and a few others a couple of times afterwards, no one returned my calls. Turns out we weren’t all friends, just people in similar situations, and I didn’t belong in that gang, the clique of hopefuls. I’d passed onto the next stage, and they didn’t want to know me any more.

Now I try to look friendly. ‘That’s so cool, bumping into you here. How’s it going? Who are you here to see?’

She doesn’t understand and then smiles. ‘Oh. I’m not acting these days.’ My face is blank. She smiles again, a little tightly. ‘I – work here? I’m Lynn’s assistant? She’s in the same department as Artie.’

‘I know Lynn,’ I say. ‘OK, so …’ I trail off, embarrassed.

‘It’s fine,’ she says, nodding so her perky ponytail bounces behind her. ‘It’s totally fine. Guess some of us have it and some of us don’t. I don’t miss the constant rejection, for sure. That time they told me no when I walked in the room, you remember that?’

I screw up my face. ‘Oh … oh, yeah, I remember. What was it for?’

‘It was The Bride and Groom, Sophie.’ She grins. ‘You should remember, we were totally hungover from being up all night drinking Bryan’s tequila?’

‘Oh, my God,’ I say, shifting my bag onto my other shoulder. ‘That night.’

‘Some of us get the right haircuts at the right time, you mean!’ Sara smiles, and says suddenly, ‘That was a totally insane evening, wasn’t it? You getting that bob, like … who was it? Eve Noel?’ She looks at my hair. ‘Still rocking it, right? You always said those bangs got you the part – maybe that’s what it took!’ She stops, and then looks alarmed. ‘Sorry,’ she says, flushing. ‘I mean, of course … you’re so good as well, you totally deserve it!’

‘No way. I was probably drunk,’ I said. ‘I’d never have got that bob if I hadn’t been totally bombed. I owe Bryan … it was Bryan, wasn’t it?’

She nods. ‘It was.’

My memory is so shit, it’s terrible. Maybe the tequila drowned my brain cells, because they were kind of crazy times. We behaved pretty badly, we didn’t have anything to lose. I was still seeing Dave, my boyfriend back in London who I met on South Street People, but I knew he was cheating on me by then. (Turns out he was cheating on me about 80 per cent of the time we were together anyway.) It’s the only slutty period of my life; maybe everyone has to have a summer like that. I’d always worked so hard and all of a sudden it was so easy. America was easy. Sunshine, friendly people, and I was young. I lived for the ocean, the cafe, the bars and the crowd I hung out with.

I loved acting, but I never thought I’d make it, to be honest. I knew I wasn’t as talented as someone like Sara, knew I wasn’t trained. I didn’t know anything about stagecraft or method; I turned up and said the lines the best way I could. Still do, I think. I’d already got further with my career than I’d ever expected to without Mum by my side all the time, and I suppose I thought I’d ride it for as long as I was allowed to. They’d find me out and I’d be sent home and so for the time being, I reasoned, I should hang loose and enjoy myself – and for once, I really, really did.

I stroke my forehead and fringe, trying to remember. ‘Bryan. He was hot, wasn’t he? Kind of Ashton Kutcher-y.’

She smiles. ‘That’s him.’

‘I think I slept with him,’ I muse.

‘Yeah, I know,’ she says, then she adds, ‘You know, I went out with him for a while. Maybe we are twins!’

There’s an awkward pause. Sara clears her throat, and stares at me after a moment. ‘Sorry,’ she says. ‘I’m being weird. But it’s really good to see you, that’s all. I never returned your calls. I suppose I was jealous. Brings back those days and it’s crazy, remembering how it used to be, I guess.’

‘You were really good,’ I say, changing the subject. She looks uncomfortable, but I press her. ‘Have you totally left it behind? That’s a real shame.’

Sara knits her fingers together. ‘Yeah. At my last audition, this guy, the director I think it was, stared at me and said, “This girl’s just an uglier Sophie Leigh. Next, please.”’ She’s smiling as she says this, but there’s an awful expression in her eyes. ‘That’s what made me give it up.’

‘That … that sucks, Sara.’ We’re silent. I sling my bag over my shoulder again and as the silence stretches on, and Sara says nothing, blurt, ‘So, Bryan! What’s he doing now?’

‘Bryan moved to New York. He has his own salon now – he’s doing really well.’ She recovers her smile again. ‘Hey, I’m super happy for him. And for you! You totally deserve your success, Sophie! It’s not only about the bob, so don’t believe people who tell you it is!’

‘Uh – thanks.’ Maybe it’s time to go. ‘Great to see you, Sara.’ I wave to T.J., my driver.

Sara calls after me, ‘You look so great, Sophie. Sorry again!’

I stride out, smiling at another WAM minion who glows when she spots me and at the doorman as I exit the building, momentarily catching the wall of fierce afternoon heat.

I climb into the car, sinking into my seat. T.J. has got me a diet root beer and some carrot and celery sticks, and there’s even a packet of crisps (which I’ll never eat, of course), all nicely laid out in the back. Chips, I should say. I’m mostly American these days, but some things never feel right. Chips are the chips you have with fish and burgers.

‘Mulberry sent you over some new stuff to pick out. Tina was unpacking it when I left and she told me to tell you,’ T.J. says. He pulls the limo away from the kerb.

‘Get Tanisha to come over.’ Tanisha is T.J.’s daughter.

‘I’ll call her. That’s kind of you. She did well on her test yesterday, Sophie, I’m real pleased with her.’

A thought occurs to me. ‘Did Deena arrive yet?’

‘I don’t know,’ T.J. says firmly. ‘She wasn’t there when I left.’ He switches topic. ‘So how’s your day going?’

I have to think for a moment. ‘Not sure.’ Now we’re gliding away from WAM, I recall what I wanted to say to Artie, and what in my hungover state I actually said. I said I would read that stupid script. I didn’t really get to talk about Eve Noel, the film I want to make one day, the mystery about her that I still don’t understand. Not because it’s complicated, because that’s obvious. But because she was new in town once like I was, and it must have started out OK for her. And I don’t know what happened to her, no one seems to know or care. I’m on every billboard in town but she was the last great film star, to my mind. Hollywood is about extremes, as someone once said. You’re either a success or a failure, there’s no in-between.

We’re turning into Sunset, right by the Beverly Hills Hotel, and I glance over at the white italic scrawl, the palm trees that reach up to the endless blue. I pull my sunglasses on and lie back against the soft leather. For a few minutes I can be still. Don’t have to worry about that wrinkle on my forehead, that bulge in my stomach, that crappy script, that feeling all the time that someone else, someone better, should be living my life, not me.

the avocado tree

Los Angeles, 1956

‘NOW, MY DEAR,’ Mrs Featherstone whispered to me as we entered the crowded room. ‘Don’t forget. Call everyone Mr So-and-So and be simply fascinated, no matter what they say. You understand?’

‘Yes, Mrs Featherstone,’ I answered obediently.

She put her hand on my back and smiled mechanically. ‘And remember, what are you called?’

‘Eve Noel.’

‘That’s it. Good girl. Your name’s Noel now. Don’t forget.’

Her thumb dug into my shoulder blade. I could feel the side of her ring pushing into my flesh and involuntarily I stepped away, then smiled politely, looking around the room.

It was a beautiful old mansion house in Beverly Hills; at least it looked old, though they told me afterwards it had only been finished last year. At the grand piano a vaguely familiar man sat playing ‘All the Things You Are’ and my skin prickled with pleasure: I loved that song. I had danced to it only two weeks ago, on our clapped-out gramophone in Hampstead. Already it seemed like a lifetime ago.

Mr Featherstone was at the bar, shaking hands, clapping shoulders. When he saw his wife, he nodded mechanically, excused himself and came over.

‘Hey,’ he said, nodding at his wife, ignoring me. ‘OK.’ He turned to the three men standing in a knot beside us, and grasped the hand of the first one.

‘Hey, fellas, I want you to meet someone. This is Eve Noel. She just arrived from London, England. She’s our new star.’ His arm was around my waist, his fingers pressed tightly against the black velvet. I wanted to shrink away.

Each man balanced his cigarette in the cut-crystal ashtray, then turned to shake my hand. I had no idea who they were. The third, younger, man narrowed his eyes, and turned away towards the piano player to ask him something. The first man smiled, kindly I thought. ‘When did you get here, Eve?’

‘Two weeks ago,’ I said.

‘Where are you staying?’ He smoothed his thinning hair across his shiny pate, an automatic gesture.

‘She’s at the Beverly Hills Hotel at the moment, and Rita is chaperoning her where necessary,’ Mr Featherstone said before I could speak. He cleared his throat importantly. ‘Eve is our Helen of Troy, we’re announcing it next week.’

‘Good for you,’ said the second man. ‘Louis, you dark horse. You swore you’d got Taylor.’

‘We went a different way. We needed someone … fresh, you know. Elizabeth’s a liability.’ His hand tightened on my waist and he smiled.

‘That’s great, that’s great,’ said the first man. ‘So – you got what you wanted from RKO, Louis? I heard they wouldn’t give you the budget.’

He and the second man smirked at each other. ‘Oh,’ said Mr Featherstone. He flashed them a quick, automatic smile. ‘Hey, we all make mistakes, don’t we.’ His voice faltered. ‘But they’re coming around. We’ll start principal photography in a couple of weeks – we don’t need the money right now. It’s only that – well, fellas, this thing is going to be huge, and I’d like a little extra, you know? I’ve been thinking, a big studio might like to share some costs. I assure you, they’d get more than their share back. MGM and David O. Selznick, ring any bells?’ He winked at the first man, as though trying to make him complicit in something. ‘But let’s not talk business in front of Miss Noel.’

‘Of course,’ said the second man. He was short and greying where the first man was short and fat with black hair; they looked similar, and it occurred to me suddenly they must be brothers. ‘How do you find LA, Miss Noel?’

‘Oh,’ I said. I moved away from Mr Featherstone’s hand. ‘I think it’s wonderful.’

‘Wonderful, eh?’

‘Oh, yes, wonderful.’ I could hear myself: I sounded dull and stupid.

He laughed. ‘How so?’

‘Oh, the …’ I couldn’t think of how to explain it. ‘The sunshine and the palm trees, and the people are so friendly. And there’s as much butter as you like in the mornings.’

He and his companions laughed; so did Mr and Mrs Featherstone, a second or two later.

‘I’m from London,’ I said.

‘No,’ the first man said, faux-incredulous. ‘I would never have guessed.’

I could feel myself blushing. ‘Well, it’s only – we had rationing until really quite recently. It’s wonderful to be able to eat what you want.’

‘Now, dear!’ Mrs Featherstone said. ‘We don’t want you talking about food all night to Joe and Lenny, do we! They’ll worry you’re going to ruin that beautiful figure of yours.’ Again the thumb, jabbing into my back.

‘Oh, no!’ I tried to smile. As with everything else here I was constantly trying to work out what the rules were; I always felt I was saying the wrong thing.

‘I’m sure that would never happen.’ I jumped. The third man, who’d not yet spoken, had turned back from the piano and was eyeing me up and down, like a woman scanning a mannequin in a shop window. He smiled, but it was almost as though he were laughing. ‘You look as if you were born to be a star,’ he said.

It was all so ridiculous, in a sense. Me, Eve Sallis, a country doctor’s daughter, who this time two months ago was a mousy drama student in London, sharing a tiny flat in Hampstead, worried about nothing so much as whether I could afford another cup of coffee at Bar Italia and what lines I had to learn for the next day’s class: there I was, at a film producer’s house in Hollywood, dressed in couture with a new name and a part in what Mr Featherstone kept referring to as ‘The Biggest Picture You Will Ever See’. Tonight a beautician had curled my short black hair and caked on mascara and eyeliner, and I’d stepped into a black velvet Dior dress and clipped on a diamond brooch, and a limousine with a driver wearing a peaked hat had driven me here, though it was a 300-yard walk away and it felt so silly, when I could have trotted down the road. But no, everything was about appearance here. If people were to believe I was a star then I had to behave like a star. Mr Featherstone had spotted me in London. He had spent a great deal of money bringing me over and I had to act the part. It was a part, talking to these old men, exactly like Helen of Troy. And I wanted to play her, more than anything.

‘Well, I’m Joseph Baxter,’ said the first man, leaning forward to take my hand again. He really was quite fat, I noticed now. ‘This is my brother Lenny, and this interesting specimen of humanity is Don Matthews. He’s a writer.’ He tapped the side of his nose. ‘First rule of Hollywood, Miss Noel. Don’t bother about the writers. They’re worthless.’

The third man, Don, nodded at me, and I blushed. ‘Hey there,’ he said. He shook my hand. ‘Well, let me welcome you to Hollywood. You’re just in time for the funeral.’

‘Whose funeral?’ I asked.

They all gave a sniggering, indulgent laugh as a waiter came by with a tray. I took a drink, desperate for some alcohol.

Don smiled. ‘Miss Noel, I’m referring to the death of the motion picture industry. You’ve heard of a little thing called television, even in Merrie Olde England, I assume?’

I didn’t like the way he sounded as though he were poking fun, and the others didn’t seem to notice. Nettled, I said, ‘The Queen’s Coronation was televised, over four years ago, Mr Matthews. Most people I know have a television, actually.’

I sounded like a prig, like a silly schoolgirl. The three older men laughed again, and Mr Featherstone raised his eyebrows at the two brothers, as if to say, ‘Look fellas, I told you so.’ But Don merely nodded. ‘Well, that’s told me. I guess someone should tell Louis then, before he starts making The Biggest Picture You Will Ever See.’

Mr Featherstone looked furious; his red nostrils flared and his moustache bristled, actually bristled. I’d discovered in my whirlwind dealings with him that he had no love for a joke. I knew what Mr Matthews was talking about, though. Every film made these days seemed to be an epic, a biblical legend, a classical myth, a story with huge spectacle, as if Hollywood in its death throes were trying to say, ‘Look at us! We do it better than the television can!’

‘We’ll come by and meet with you properly,’ Mr Featherstone told Joe and his brother. ‘I’d like for you to get to know Eve. I think she’s very special.’

‘We should … arrange that.’ Joe Baxter was looking me up and down once more. ‘Miss Noel, I agree with Louis, for once. It’s a pleasure to meet you.’ He took my hand. His was large, soft like a baby’s, and slightly clammy. He breathed through his mouth, I noticed. I wondered if it was adenoids. ‘Yes,’ he said to Mr Featherstone. ‘Bring Miss Noel over, we’ll have that meeting. Maybe we’ll – ah, run into you again tonight.’

‘Bye, fellas.’ Don stubbed out his cigarette, and winked at me. ‘Miss Noel, my pleasure. Remember to enjoy the sunshine while you’re here. And the butter.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.