Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

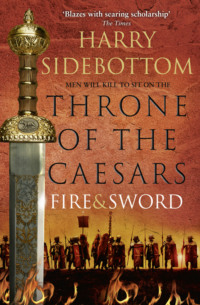

Kitabı oku: «Fire and Sword», sayfa 2

PART I:

CHAPTER 1

Rome

The Temple of Concordia Augusta, Six Days before the Kalends of April, AD238

‘Dead? Both of them? Are you certain?’

Standing before the Senate of Rome, the old freedman was unabashed by the Consul’s brusque questions.

‘Gordian the Younger died on the field of battle. When Gordian the Elder ordered me to convey what remained of his household to safety, his mind was set on suicide.’

Licinius Rufinus leant forward on the Consular tribunal. ‘Was his bodyguard with him?’

‘He was alone.’

‘You did not see him take his life?’

This was pointless. Pupienus sat back, let his gaze shift around the huge interior of the temple, run over the myriad sculptures and paintings, part obscured by the gloom. Valens had been A Cubiculo to Gordian the Elder forever, since before the flood. He had served well when his master was alive, and would do the same now his master was dead. There was no doubting his evidence. The Emperors that the Senate had acclaimed were dead. No amount of juristic interrogation could bring them back.

Opposite Pupienus a painting by Zeuxis hung over the heads of the Senators. Marsyas was bound to the tree hand and foot, naked, already twisted in agony. At his feet the Scythian slave was sharpening the knife, looking up at the man whose skin he would peel from his living body. With the Gordiani dead, every Senator in the temple could expect some similar fate when Maximinus came down from the North and took Rome. Maximinus was a Thracian, a barbarian. They were no different from Scythians; strangers to reason and pity. Clemency was not in their nature.

Valens was dismissed, and walked out. Pupienus envied the aged ex-slave. The very obscurity of his station might prove his salvation. There was no such hope for himself. No hope at all for the man appointed Prefect of the City to oversee Rome in the name of the Gordiani. None whatsoever for the man complicit in the killing of his predecessor, Sabinus, Maximinus’ appointee. Too late for a change of heart, and compromise was not an option. Some other, desperate course must be taken.

As presiding magistrate Licinius called on the Conscript Fathers to give their advice.

In the nervous silence, Pupienus turned the ring on the middle finger of his right hand, the ring containing the poison.

To the relief of all, Gallicanus sought permission to address the meeting.

Pupienus regarded the speaker with disfavour. A tangle of unwashed hair and beard, a homespun toga, no tunic, bare feet; an ostentatious parade of self-proclaimed antique virtue. All it needed was a staff and a wallet for alms, and he would have been Diogenes reborn. Pupienus thought Cynic philosophers were meant to abstain from politics; certainly they should not possess the property qualification of a Senator. He trusted his distaste did not show on his face.

‘A tyrant is descending upon us. A monster stained with innocent blood. Conscript Fathers, we must recover our ancestral courage.’

All true enough, although Pupienus considered that more than rhetoric was needed. Specific proposals were required at this desperate pass. The Senate hated Maximinus for killing their friends and relatives, for the continual exactions to pay for the unwinnable northern wars. They loathed him for the lack of respect shown to their order. Since his elevation, he had never set foot in the Curia, or even visited Rome. Ultimately they despised him for not being one of them. When news came of the revolt of the Gordiani in Africa, it had seemed a gods-given salvation. The Senate had voted them the purple, had denied Maximinus and his son fire and water, had declared them enemies of Rome. The Senate had acted hastily. It had gambled, and it had lost. There was nothing for it now but to gamble again. One last throw of the dice: elect a new Emperor.

‘A ravening tyrant is coming from the savage North. We must defend our families, our homes, the temples of our gods. We must stand in the ranks ourselves. To elect another tyrant in the hope that he will defend us from the one already approaching is insanity.’

The words irritated Pupienus. No candidate had yet been nominated. It was too early for personal invective. Unless … surely Gallicanus was not going to propose the mad scheme he had aired in Pupienus’ house three years earlier, when the news had come that the Emperor Alexander had been murdered?

‘Place a man above the laws, and he will become lawless. Power corrupts. Even should a man be found with the virtue to resist temptation, a man who would rule for others not himself, history has shown that the heirs to his position will be tyrants, ruling for their own perverse pleasure.’

The small philosophic coterie led by Gallicanus’ especial friend Maecenas shook back the threadbare folds of their togas and applauded. The majority of the Senators, all better apparelled, sat in silence.

‘I am not suggesting anything new, anything foreign. The gods forbid we should institute a radical democracy. The Athenian past demonstrates how quickly such a constitution slides into mob rule. I do not even propose we Senators take power, rule as an aristocracy. Every such state inevitably has been deformed into an oligarchy, where a few rich men trample down their fellow citizens. No, I argue we should return to our ancestral government. Rome became great under a free Republic. Every order of men knew their duties and their place. The Consuls embodied the monarchic element, the Senate the aristocratic, the assemblies of the people the democratic. All was balanced in harmony. As a Republic, Rome defeated Hannibal. As a Republic, Rome will defeat Maximinus. We have already elected a board of twenty men to prosecute the war. We have no need of an Emperor, no need to set the boots of an autocrat over our heads. Conscript Fathers, we need do nothing to restore the Republic. The providence of the gods who watch over Rome has made the Republic live again. Let us seize our liberty! Let libertas be our watchword!’

Gallicanus, archaic probity personified, glared defiance at the unmoved togate benches. Maecenas came forward, and put his arm around the shoulders of his amicus, said something soft in his ear. Gallicanus smiled, no longer a barking Cynic dog, but, despite his more than forty years, an unsure youth seeking approbation.

Pupienus was mildly surprised when Fulvius Pius took the floor. Inoffensiveness, not ability, had seen Pius rise to the Consulship then the Board of Twenty. His career had been marked by neither independence of thought or action, nor much display of courage.

‘Fine words for a lesson in philosophy, fine words to address two or three pupils. Utterly inappropriate to this august house.’

Since his election to the Twenty, not only had a certain initiative surfaced in Pius, but an unexpected asperity.

‘I will not enter into a philosophical dialogue with Gallicanus. This is not the time or place to debate the tenets of the schools. Instead we should face realities. No one regrets the passing of the free Republic more keenly than me. The busts of Cato, Brutus and Cassius have pride of place in my house. But the free Republic is nothing more than a pleasant memory. If we could not see that for ourselves, long ago the historian Tacitus taught us that the rule of an Emperor and the continuance of our empire are inextricably linked.’

Still locked in an embrace, Gallicanus and Maecenas glowered at the speaker.

‘Only a handful of men, beguiled by the high-sounding words of philosophy, want the return of the long dead Republic. The majority of all orders desire the status quo. The provincials can appeal to the Emperor against unjust decisions of their governors. The plebs urbana look to the Emperor to give them the sustenance of life, and the spectacles that make it worth living. The soldiers receive their pay from the Emperor, and give him their oath. What of the Praetorians? Their sole reason for existence is to guard the Emperor. And what of us, Conscript Fathers? With no Emperor to restrain them, the ambitions of certain Senators would again tear the Republic apart. A welter of civil strife would consume our armies. The barbarians would pour over the frontiers, sack our cities, drown our dominion in blood.’

‘Not if we return to the ways of our ancestors,’ Gallicanus shouted.

Pius smiled, as if patiently correcting a schoolboy. ‘The mos maiorum was no defence against Caesar or Augustus. We do not live in Plato’s Republic. Let us face facts as statesmen. We must have an Emperor to lead our defence. The fate of the Gordiani shows that the man elected must command legions. As the armies in the North are with Maximinus, let us send the purple to a governor of one of the great provinces in the East, begging him to march with all haste to save Rome.’

Gallicanus bellowed defiance. ‘Cowardice! The gods may never grant us another opportunity for libertas!’

Amidst an outcry of disapproval – Sit down! Leave the floor! – Maecenas pulled his friend back to his seat.

‘Conscript Fathers.’ Licinius struggled to be heard over the clamour. ‘Senators of Rome!’

Eventually the house heeded the Consul.

‘Conscript Fathers, the distinguished Consular Fulvius Pius has given us good advice. In all but one respect. The very practicalities he urges mitigate against the election of an eastern governor. Their allegiance is unknown. Indeed the governor of Cappadocia, Catius Clemens, was one of the men who put Maximinus on the throne.’

Pupienus was not alone in looking at Clemens’ younger brother. Catius Celer sat modestly a few rows back, among the ex-Praetors and other Senators who had not yet been Consul. His face betrayed nothing. He had been quick to acknowledge the Gordiani. Many great houses had the foresight to survive times of troubles by having relatives on both sides.

‘That aside, there are factors of distance and time. With favourable winds, a despatch might reach Syria in days, but by land or sea an army could not return for months. Maximinus will be upon us long before. We must acclaim one of our own. The Senate already has elected the Board of Twenty to defend the Res Publica. The choice should be made from among their number.’

A low murmur of speculation filled the temple.

Licinius continued. ‘A decision of this importance is not to be taken on a whim. I propose to adjourn the house, to allow time for careful consideration, to seek to discern the will of the gods, and to allow us to mourn the Gordiani with due piety. The Senate will reconvene on a propitious day, when the auguries are good. Conscript Fathers, we detain you no longer.’

The doors of the temple were opened. Light filled the cella, banishing the dark to rafters, corners, and seldom-frequented spaces behind the statuary.

Pupienus wholeheartedly believed in the traditions of the Senate, but he needed to be alone. He told his sons to accompany the presiding Consul home as his representatives, and requested his close friends to join him later for dinner.

It took time for the near four hundred Senators in attendance to make their way out into the sunshine. Some lingered, talking in little groups, covertly eyeing the members of high standing and influence. Intrigue and ambition, two things at the heart of their order, had, at least for the moment, driven out fear. Many looked at Pupienus as he sat unmoving and alone.

Pupienus regarded Marsyas: naked, racked, ribs lifted high, skin stretched, taut and vulnerable. No escape from the knife. Marsyas had challenged Apollo. It had been his downfall, brought him to his hideous end. Marsyas was not the only one destroyed by ambition. Some philosophers castigated ambitio as a vice, others held it a virtue. Perhaps it was composed of both qualities. Pupienus was ambitious. He had risen high. Yet was the ultimate ambition – the throne itself – too dangerous for a man whose life was predicated on a lie? Pupienus knew that if the secret that he had guarded all his life were revealed his many achievements would be as nothing, and he would be ruined and broken.

The temple was almost empty, just a few attendants clearing away the paraphernalia of the meeting. Pupienus’ secretary, Fortunatianus, was waiting on the threshold. Pupienus beckoned him.

Fortunatianus knew his master. Without words, he handed Pupienus the writing block and stylus.

Pupienus opened the hinged wooden blocks, regarded the smooth wax. His mind worked best with something on which to focus, some visual mnemonic. There were only nine of the Board of Twenty in Rome. On receipt of the news would ambition drive others to desert their posts and rush to the city? What of Menophilus at Aquileia, or Rufinianus in the Apennines? Best leave them aside, deal with such circumstances if they arose. For now there were only nine men eligible for election in Rome, only nine men in this strange situation thought capable of empire. He ordered them, and wrote a list, annotated only in his thoughts.

Capax imperii

Allies

Pupienus – Prefect of the City, experienced and resourceful, accustomed to command, yet a novus homo, standing on the edge of a precipice

Tineius Sacerdos – a respectable nobleman, father of the wife of Pupienus’ elder son, loyal, but lacking dynamism

Praetextatus – another nobilis, ill-favoured father of the ill-favoured new bride of Pupienus’ younger son, a more recent friend of unproven fidelity, apparently without competence

Opponents

Gallicanus – a violent, hirsute, yapping Cynic

Maecenas – his intimate, somewhat better groomed, yet still rendered intransigent by philosophic pretentions to virtue

Others

Licinius – a Greek novus homo, once an imperial secretary, intelligent and enterprising

Fulvius Pius – another nobilis, formerly of little account, now growing in stature

Valerian – confidant of the dead Gordiani, not altogether without merit, a follower not a leader

Balbinus – repellent mixture of complacency and cupidity, like the majority of the patricians

Three, including himself, who could be expected to favour the candidature of Pupienus. It could be assumed that Gallicanus and Maecenas, beguiled by dreams of a dead Republic, would oppose any aspirant to sole power. Pupienus needed to win over two of the remaining four. Yet it was not just the men themselves. Everything depended on the votes they could bring. The issue would be decided by decree of the whole Senate.

Which two must he attempt to bring over?

Much would tell against Licinius among traditional Senators: his Hellenic origins – Greeks were naturally untrustworthy – his early employment – a secretary at another’s beck and call – even his intelligence – Greeks were far too clever for their own good, and always, always talking.

Fulvius Pius had a long career behind him, and was distantly related to the Emperor Septimius Severus. Familial ties and propinquities of office might sway a few to his side in the house, but nowhere near enough.

Valerian had been at the heart of the brief, doomed regime of the Gordiani. The death of the principals would have robbed their faction of appeal to the majority of Senators. Yet there were issues to weigh beyond the Curia. Pupienus himself commanded the six thousand soldiers of the Urban Cohorts. All the other military forces near at hand – the thousand Praetorians and seven thousand men of the vigiles in Rome, and the thousand swords of the 2nd Legion in the Alban Hills – were led by equestrian officers, every one of whom was bound by the ties of patronage to the Domus Rostrata, the noble house of the Gordiani. If Valerian was in his camp, Pupienus could put a noose of steel around the Senate House.

And then there was Balbinus. A porcine face on a corpulent body, both bloated by a lifetime of indulgence and perversity. A soul where stupidity vied with low cunning, and profound indolence with vast ambition. It was impossible to measure how much Pupienus despised the man. Yet Balbinus was a kinsman of the divine Emperors Trajan and Hadrian, a member of the Coelli, a clan that went back to the foundation of the free Republic, and, by their own account, beyond history itself, all the long way to Aeneas and the gods. Irrespective of his character, centuries of familial wealth and public honours, an atrium filled with smoke-blackened portrait busts, endowed Balbinus with a status that could command the votes of many Senators.

In politics often emotion must be set aside. Pupienus would have to stomach the patrician’s sneers and jibes. Rome is less your lodging house than your stepmother. Beguile us with your ancestry; tell us the great deeds of your father. But what bait could Pupienus dangle before those slobbering jaws, what prize so glittering that it could pierce Balbinus’ lethargy, and induce him to prevail on his relatives, friends and clients in the Curia to vote imperial honours to a man he regarded as an upstart, little better than a slave?

The honours of an Emperor. Pupienus reviewed the purple, the ivory throne, the sacred fire. In a private enterprise one could press on or draw back, commit oneself more deeply or less. But in the pursuit of an empire there was no mean between the summit and the abyss. To be Emperor was to live on the stage of a public theatre, every movement and word visible. There was no mask. One’s inner being and past were stripped bare. Certainly too close a scrutiny for a man with a secret lodged less than two hundred miles from Rome. If he were to proceed, Pupienus would have to go one last time to Volaterrae, and bury his past. It was a task he had prayed never to have to undertake. Everything decent cried out against it. But to bid for the throne all emotion must be set aside.

CHAPTER 2

Northern Italy

The Aesontius River, Two Days before the Kalends of April, AD238

If they went on, any scout or spy concealed in the farm would see them. Menophilus had halted his small column well back from the treeline. They would wait and watch. There were about three hours of daylight left. This close to the enemy, unnecessary risks were to be avoided. Quietly, he told his men to dismount, take the weight from the backs of their horses.

The farm was still in the spring sunshine; red tiles and whitewashed walls, black holes where the doors and shutters had been removed. Big, round wine barrels, all empty. No animals, not even a chicken pecking in the dirt. No smoke from the chimneys. No sign of life. Menophilus thought of his home, and hoped war never came to distant Apulia.

A small unpaved road ran to the farm from the south, then turned north-east and disappeared into the timber. Menophilus had avoided it, instead leading his ten men laboriously up through the woods that bordered the river. The going had been soft, progress slow, and the horses were tired. The rest would do them good.

A movement in the yard. A figure walked from the barn and went into the house. Although the distance was too great to make out the individual with certainty, he had the bearing of a soldier. It could not be otherwise. All civilians had been forcibly evacuated on Menophilus’ orders. Despite the destruction of the bridge, at least a part of the army of Maximinus had got across the Aesontius.

The hostile piquet was not an insurmountable complication. They could not be much more than half a mile from the site of the demolished bridge. Menophilus gave the Optio the watchwords – Decus et Tutamen – and his instructions. Two of the most reliable men were to lie up and observe the farm. The junior officer and the rest of the troopers were to lead all the horses back to a clearing; the one with a tree that had been hit by lightning. Let the horses graze, but they were to remain saddled, their riders with them, ready to move out. Menophilus and the guide would continue the reconnaissance on foot. If they had not returned by dawn tomorrow, the Optio was to withdraw the way they had come. When he got back to Aquileia, he was to inform Crispinus that the Senator had sole command of the defence of the town.

Menophilus thought about Crispinus. In Rome his initial impression of his fellow member of the Board of Twenty had not been completely positive. It had been difficult to see beyond the long beard, with its philosophical pretentions, and the ponderous, over-dignified ways of moving and talking. Although Crispinus had much experience of command, political necessity rather than military expertise had saddled Menophilus with him as joint commander of Aquileia. Yet as the two men had prepared to defend the city against Maximinus in the name of the Gordiani, a certain respect had grown between them. If Menophilus fell, Aquileia would remain in safe hands.

The thud of hooves was deadened by the leafmould under the trees, but no body of cavalry moved silently. The breeze was from the north, and Menophilus doubted that the creak of leather and the clink of metal fittings, the occasional whicker of a horse, would carry.

When there was just the sound of the gentle wind in the trees, he gave his attention to the way ahead. The farm stretched towards the Aesontius: the house, then the yard with the massive wine barrels, the barn and some sheds, a tiny meadow, and a steep track cut down through the trees to the river. There was no cover to cross the track, but the incline and the outbuildings might obscure the view from the dwelling to the riverbank.

Menophilus checked that his guide was ready. Marcus Barbius smiled, tight-lipped. The youth had every right to be nervous. It would have been better to have a soldier. But none of the men of the 1st Cohort Ulpia Galatarum, the only troops in Aquileia, knew the country. The young equestrian’s family owned these lands. In more peaceful times, the farm was occupied by one of their tenants.

The two of them graded down through beech trees and elms until they were among the willows by the stream. The Aesontius was running high and fast, its green waters foaming white where they surged over submerged banks of shingle.

When they reached the path, Menophilus crouched and peered around the trunk of a tree. From down here, only the red roof of the farmhouse was visible over the barn. Of course, if men were stationed in the outbuildings, they would have an uninterrupted view down to the river. The nearest shed was no more than fifty paces distant.

Menophilus stood. ‘We will walk across. They may assume we are two of them.’

Barbius did not speak, but looked dubious.

‘If we run, it will arouse suspicion.’

Barbius still said nothing. He appeared little reassured. Perhaps fear had robbed the youth of speech.

Both of them were wearing tunic, trousers, and boots, and had sword and dagger, one on each hip. They looked like off-duty soldiers. To move quietly, before leaving, Menophilus had removed the memento mori – a silver skeleton – and the other ornaments from his equipment. Now he took the long strap of his belt, and twirled the metal end, as was the habit of soldiers at their ease.

With his left hand, he took Barbius by the elbow, and propelled him out across the path.

Let us be men.

One step, two, three. The strap-end thrumming. Let us be men. Not looking up at the farm. At every step, the fear of an outcry, or the terrible whistle of an arrow. Five steps, six.

Eight paces, and they were back in cover.

Menophilus dropped to the ground. Heart hammering, he crawled back to the edge of the path.

Once again, he gazed up from behind the bough of a tree.

Nothing moved. Utter stillness.

He watched for some time. From this point on, the piquet at their backs, escape would be infinitely more difficult.

At length, somewhat satisfied, heart beating more normally, he wriggled backwards to where Barbius waited.

They went cautiously up the bank, flitting from tree to tree through the dappled shadows.

Ahead was a blaze of light where the road meandered through the woods.

Again, Menophilus stopped, took cover, and watched and waited.

The backroad was grey, dusty, and empty. A pair of swallows low over it, banking and swooping. A sign of bad weather to come.

Telling Barbius to watch both directions, Menophilus walked out onto the byway, studied it. The distinct marks of military hobnailed boots. No impressions of hooves or hipposandals. The surface was powdery, not tramped down. Only a few of the enemy had gone up to the farm, all of them on foot.

Returning to the shade, Menophilus and Barbius went through the trees parallel to the road.

Soon the road joined a grander, paved version of itself. The Via Gemina was the main route from Aquileia to the Julian Alps, and on to Emona and the Danubian frontier. When war did not threaten, there would be many travellers. Today it was deserted. There were no guards at the junction.

A final rise, and the Via Gemina dipped down to the Aesontius. The river here was very broad. Usually shallow, now it was swollen with spring melt from the mountains. All that remained of the central sections of the Pons Sonti were the stubs of piers, the water breaking around them, tugging at their loosened stones. On the far bank was the beginning of a pontoon bridge. The first two barges were in place. A large body of soldiers was manhandling the next down the bank. Around them was the bustle of disciplined activity. Gangs of men braked wagons down the descent, and laboured to unload huge cables and innumerable planks.

Below Menophilus, at the foot of the slope, a small rowing boat was moored to the near bank. Here all was quiet. A detachment of troops, no more than a hundred, lounged in the shade. An officer had a detail of ten men standing in the road, about fifty paces from their resting companions. Menophilus cast about, and found a tangle of undergrowth from which to observe.

The shadows lengthened, and across the river the work went on. On the near bank, the soldiers passed around wineskins. From time to time, individuals wandered a little downstream to relieve themselves. Menophilus unhinged a writing block, and made occasional, cryptic notes.

It was in moments of inactivity that his grief threatened to unman him. What was the point of this reconnaissance? Of any of it? The risk and the striving; all for what? His friends were dead. Gordian the Father and Gordian the Son, both dead. Of course, he had known they were mortal. Death was inevitable. Friends were like figs; they did not keep.

Philosophy was a thin and inadequate consolation. If they were his friends, they would not want him in misery. But they were beyond that. They had escaped. The life of man was but a moment, his senses a dim rushlight, his body prey to disease, his soul an unquiet eddy, his fortune dark; a brief sojourn in an alien land.

True, they had lived as they wished, and they had met their deaths well. Gordian the Son struck down on the field of battle, opposing the forces of the tyrant. Gordian the Father by his own hand, the decision his own. The world was wrong to see the rope as womanish. Everywhere you looked, you found an end to your suffering. See that short, shrivelled, bare tree? Freedom hung from its branches. What was the path to freedom? Any vein in your body.

Life was a journey. Unlike any other, it could not be curtailed. No life was too short, if it had been well lived. Menophilus knew he should not rail against what could not be changed. Instead he should be grateful for the time he had been granted with his friends. But the pain of their loss cut like a knife.

The shadows were lengthening. Dusk had fallen down at the waterside. Torches sawed in the breeze, as men continued to labour in the gloom.

Menophilus had gathered some useful intelligence. It was carefully noted in his writing tablet. From the bull on their standard, he had learnt that the men on the near bank were from the 10th Legion Gemina, which was based at Vindobona in Pannonia Superior. Evidently they had been ferried over a few at a time by the one little rowing boat. There were not yet many of them on the Aquileian side of the Aesontius. From their demeanour, they were relaxed and confident. They knew that the rebels had no regular army to bring against them in the field. No attack was expected. On the far side of the water, the prefabricated materials of the pontoon bridge, and the proficiency of their assembly indicated that it belonged to the imperial siege train. Another twenty-four hours should see its completion.

What he had discovered was not enough. He needed to know what other troops accompanied the 10th Legion, or, at least, form some idea of their numbers. He would wait. The night might provide more answers.

Darkness fell, and the wind picked up. It had shifted into the south-west. From that direction it often brought rain in these regions. A downpour would further swell the river, hamper the bridge-building. A difficult business manoeuvring the barges in a strong current, and there was the danger of debris swept downriver. If it rained heavily, the pontoon might not be ready for a couple of days. Menophilus committed that to memory; it was too dark to write.

Clouds, harbingers of a storm, scudded across the moon. The wind soughed through the foliage, creaking branches together. The woods were alive with the scuttling and the choked-off cries of nocturnal predator and prey.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.