Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

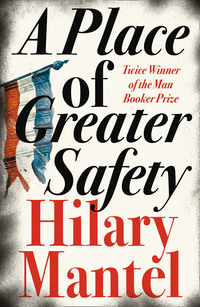

Kitabı oku: «A Place of Greater Safety», sayfa 6

‘I can’t think why you don’t write and encourage him.’

‘Yes, perhaps I shall. You see, I do agree that I can’t go on like this. I have had a little verse published – oh, nothing really, just a modest start. I’d rather write than anything – well, as you can imagine, with my disabilities it’s a relief not having to talk. I just want to live very quietly – preferably somewhere warm – and be left alone till I can write something worthwhile.’

Already, d’Anton did not believe this. He recognized it as a disclaimer that Camille would issue from time to time in the hope of disguising the fact that he was an inveterate hell-raiser. ‘Don’t you care for anyone respectable?’ he asked.

‘Oh yes – I care for my friend de Robespierre, but he lives in Arras, I never see him. And Maître Perrin has been kind.’

D’Anton stared at him. He did not see how he could sit there, saying ‘Maître Perrin has been kind.’

‘Don’t you mind?’ he demanded.

‘What people say? Well,’ Camille said softly, ‘I should prefer not to be an object of general odium, but I wouldn’t go so far as to let my preference alter my conduct.’

‘I’d just like to know,’ d’Anton said. ‘I mean, from my point of view. Whether there’s any truth in it.’

‘Oh, you mean, because the sun will be up in an hour, and you think I’ll run down to the Law Courts and tell everybody I spent the night with you?’

‘Somebody told me … that is, amongst other things they told me … that you were involved with a married woman.’

‘Yes: in a way.’

‘You do have an interesting variety of problems.’

Already, by the time the clock struck four, he felt he knew too much about Camille, and more than he was comfortable with. He looked at him through a mist of alcohol and fatigue, the climate of the years ahead.

‘I would tell you about Annette Duplessis,’ Camille said, ‘but life’s too short.’

‘Is it?’ D’Anton has never thought about it before. Creeping towards his future it sometimes seems long, long enough.

IN JULY 1786 a daughter was born to the King and Queen. ‘All well and good,’ said Angélique Charpentier, ‘but I expect she’ll be needing some more diamonds to console her for losing her figure.’

Her husband said, ‘How would we know if she’s losing her figure? We never see her. She never comes. She has something against Paris.’ It was a matter of regret to him. ‘She doesn’t trust us, I think. But of course she is not French. She is far from home.’

‘I am far from home,’ Angélique said heartlessly. ‘But I don’t run the nation into debt because of it.’

The Debt, the Deficit – these were the words on the lips of the café’s customers as they occupied themselves in trying to name a figure. Only a few people had the ability to imagine money on this scale, the café believed; they thought it was a special ability, and that M. Calonne, now the Comptroller-General, had not got it. M. Calonne was a perfect courtier, with his lace cuffs and lavender-water, his gold-topped cane and his well-attested greed for Perigord truffles. Like M. Necker, he was borrowing; the café thought that M. Necker’s borrowing had been considered, but that M. Calonne’s borrowing stemmed from a failure of imagination and a desire to keep up appearances.

In August 1786 the Comptroller-General presented to the King a package of proposed reforms. There was one weighty and pressing reason for action: one half of the next year’s revenues had already been spent. France was a rich country, M. Calonne told its sovereign; it could produce many times more revenue than at present. And could this fail to add to the glory and prestige of the monarchy? Louis seemed dubious. The glory and prestige were all very well, most agreeable, but he was anxious to do only what was right; and to produce this revenue would require substantial changes, would it not?

Indeed, his minister told him, from now on everybody – nobles, clergy, commons – must pay a land tax. The pernicious system of tax exemptions must be ended. There must be free trade, the internal customs dues must be abolished. And there must be some concessions to liberal opinion – the corvée must be done away with completely. The King frowned. He seemed to have been through all this before. It reminded him of M. Necker, he said. If he had thought, it would have reminded him of M. Turgot, but by now he was getting muddled.

The point is, he told his minister, that though he personally might favour such measures, the Parlements would never agree.

That, said M. Calonne, was a most cogent piece of reasoning. With his usual unerring accuracy, His Majesty had pinpointed the problem.

But if His Majesty felt these measures were necessary, should he allow himself to be baulked by the Parlements? Why not seize the initiative?

Mm, the King said. He moved restlessly in his chair, and looked out of the window to see what the weather was doing.

What he should do, Calonne said, was to call an Assembly of Notables. A what? said the King. Calonne pressed on. The Notables would at once be seized by a realization of the country’s economic plight, and throw their weight behind any measures the King deemed necessary. It would be a bold stroke, he assured the King, to create a body that was inherently superior to the Parlements, a body whose lead they would have to follow. It was the sort of thing, he said, that Henri IV would have done.

The King pondered. Henri IV was the most wise and popular of monarchs, and the very one that he, Louis, most desired to emulate.

The King put his head in his hands. It sounded a good idea, the way Calonne put it, but all his ministers were smooth talkers, and it was never quite as simple as they made out. Besides, the Queen and her set … He looked up. The Queen believed, he said, that the next time the Parlements got in his way they should simply be disbanded. The Parlements of Paris, all the provincial Parlements – chop, chop, went the King. All gone.

M. Calonne quaked when he heard this reasoning. What did it offer but a vista of acrimonious dealings, a decade of wrangling, of vendettas, of riots? We have to break out of this cycle, Your Majesty, he said. Believe me – please, you must believe me – things have never been this bad before.

GEORGES-JACQUES came to M. Charpentier, and he put his cards on the table. ‘I have a bastard,’ he said. ‘A son, four years old. I suppose I should have told you before.’

‘Why so?’ M. Charpentier gathered his wits. ‘Pleasant surprises should be saved up.’

‘I feel a hypocrite,’ d’Anton said. ‘I was just lecturing that little Camille.’

‘Do go on, Georges-Jacques. You have me riveted.’

They’d met on the coach, he said, on his first journey to Paris. She’d given him her address, he’d called on her a few days later. Things had gone on from there – well, M. Charpentier could imagine, perhaps. No, he was no longer involved with her, it was over. The boy was in the country with a nurse.

‘You offered her marriage, of course?’

D’Anton nodded.

‘And why wouldn’t she marry you?’

‘I expect she took a dislike to my face.’

In his mind’s eye he could see Françoise raging round her bedroom, aghast that she was subject to the same laws as other women: when I marry I want it to be worth my while, I don’t want some clerk, some nobody, and you with your passions and your self-conceit running after other women before the month’s out. Even when the baby was kicking inside her, it had seemed to him a remote contingency, might happen, might not. Babies were stillborn, they died in the first few days; he did not hope for this to happen, but he knew that it might.

But the baby grew, and was born. ‘Father unknown’, she put on the birth certificate. Now Françoise had found the man she wanted to marry – one Maître Huet de Paisy, a King’s Councillor. Maître Huet was thinking of selling his position – he had something else in mind, d’Anton did not inquire what. He was offering to sell it to d’Anton.

‘What’s the asking price?’

D’Anton told him. Having received his second big shock of the afternoon, Charpentier said, ‘That’s simply not possible.’

‘Yes, I know it’s vastly inflated, but it represents my settlement for the child. Maître Huet will acknowledge paternity, it will all be done in the correct legal form and the matter will be behind me.’

‘Her family should have made her marry you. What kind of people can they be?’ He paused. ‘In one sense the matter will be behind you, but what about your debts? I’m not sure how you can raise that amount in the first place.’ He pulled a piece of paper towards him. ‘This is what I can let you have – let’s call it a loan for now, but when the marriage contract is signed I waive the debt.’ D’Anton inclined his head. ‘I must have Gabrielle well set up, she’s my only daughter, I mean to do right by her. Now, your family can come up with – what? All right, but that’s little enough.’ He jotted down the figures. ‘How can we cover the shortfall?’

‘Borrow it. Well, that’s what Calonne would say.’

‘I see no other solution.’

‘I’m afraid there is another part to this deal. You won’t like it. The thing is, Françoise has offered to lend me the money herself. She’s well-off. We haven’t gone into the details, but I don’t suppose the interest rate will be in my favour.’

‘That’s iniquitous. Good God, what a bitch! Wouldn’t you like to strangle her?’

D’Anton smiled. ‘Oh, yes.’

‘I suppose you are quite sure the boy’s yours?’

‘She wouldn’t have lied to me. She wouldn’t dare.’

‘Men like to think that …’ He looked at d’Anton’s face. No, that was not the way out. So be it – the child was his. ‘It is a very serious sum of money,’ he said. ‘For one night’s work five years ago it seems disproportionate. It could dog you for years.’

‘She wants to wring what she can out of me. You can understand it, I suppose.’ After all, she had the pain, he thought, she had the disgrace. ‘I want to get it settled up within the next couple of months. I want to start off with Gabrielle with a clean slate.’

‘I wouldn’t call it a clean slate, exactly,’ Charpentier said gently. ‘That’s just what it isn’t. You’re mortgaging your whole future. Can’t you –’

‘No, I can’t fight her over it. I was fond of her, at one time. And I think of the boy. Well, ask yourself – if I took the other attitude, would I be the kind of person you’d want for a son-in-law?’

‘Yes, I see that, don’t mistake me, it’s just that I’m old and hard-boiled and I worry about you. When does this woman want the final payment?’

‘She said ’91, the first quarter day. Do you think I should tell Gabrielle about this?’

‘That’s for you to decide. Between now and your wedding, can you contrive to be careful?’

‘Look, I’ve got four years to pay this off. I’ll make a go of things.’

‘Certainly, you can make money as a King’s Councillor. I don’t deny that.’ M. Charpentier thought, he’s young, he’s raw, he has everything to do, and inside he cannot possibly be as sure as he sounds. He wanted to comfort him. ‘You know what Maître Vinot says, he says there are times of trouble ahead, and in times of trouble litigation always expands.’ He rolled his pieces of paper together, ready for filing away. ‘I daresay something will happen, between now and ’91, to make your fortunes look up.’

MARCH 2 1787. It was Camille’s twenty-seventh birthday, and nobody had seen him for a week. He appeared to have changed his address again.

The Assembly of Notables had reached deadlock. The café was full, noisy and opinionated.

‘What is it that the Marquis de Lafayette has said?’

‘He has said that the Estates-General should be called.’

‘But the Estates is a relic. It hasn’t met since –’

‘1614.’

‘Thank you, d’Anton,’ Maître Perrin said. ‘How can it answer to our needs? We shall see the clergy debating in one chamber, the nobles in another and the commons in a third, and whatever the commons propose will be voted down two to one by the other Orders. So what progress –’

‘Listen,’ d’Anton broke in, ‘even an old institution can take on a new form. There’s no need to do what was done last time.’

The group gazed at him, solemn. ‘Lafayette is a young man,’ Maître Perrin said.

‘About your age, Georges.’

Yes, d’Anton thought, and while I was poring over the tomes in Vinot’s office, he was leading armies. Now I am a poor attorney, and he is the hero of France and America. Lafayette can aspire to be a leader of the nation, and I can aspire to scratch a living. And now this young man, of undistinguished appearance, spare, with pale sandy hair, had captured his audience, propounded an idea; and d’Anton, feeling an unreasoning antipathy for the fellow, was compelled to stand here and defend him. ‘The Estates is our only hope,’ he said. ‘It would have to give fair representation to us, the commons, the Third Estate. It’s quite clear that the nobility don’t have the King’s welfare at heart, so it’s stupid for him to continue to defend their interests. He must call the Estates and give real power to the Third – not just talk, not just consultation, the real power to do something.’

‘I’ll believe it when I see it,’ Charpentier said.

‘It will never happen,’ Perrin said. ‘What interests me more is Lafayette’s proposal for an investigation into tax frauds.’

‘And shady underhand speculation,’ d’Anton said. ‘The dirty workings of the market as a whole.’

‘Always this vehemence,’ Perrin said, ‘among people who don’t hold bonds and wish they did.’

Something distracted M. Charpentier. He looked over d’Anton’s shoulder and smiled. ‘Here is a man who could clarify matters for us.’ He moved forward and held out his hands. ‘M. Duplessis, you’re a stranger, we never see you. You haven’t met my daughter’s fiancé. M. Duplessis is a very old friend of mine, he’s at the Treasury.’

‘For my sins,’ M. Duplessis said, with a sepulchral smile. He acknowledged d’Anton with a nod, as if perhaps he had heard his name. He was a tall man, fifty-ish, with vestigial good looks; he was carefully and plainly dressed. His gaze seemed to rest a little behind and beyond its object, as if his vision were unobstructed by the marble-topped tables and gilt chairs and the black limbs of city barristers.

‘So Gabrielle is to be married. When is the happy day?’

‘We’ve not named it. May or June.’

‘How time flies.’

He patted out his platitudes as children shape mud-pies; he smiled again, and you thought of the muscular effort involved.

M. Charpentier handed him a cup of coffee. ‘I was sorry to hear about your daughter’s husband.’

‘Yes, a bad business, most upsetting and unfortunate. My daughter Adèle,’ he said. ‘Married and widowed, and only a child.’ He addressed Charpentier, directing his gaze over his host’s left shoulder. ‘We shall keep Lucile at home for a while longer. Although she’s fifteen, sixteen. Quite a little lady. Daughters are a worry. Sons, too, though I haven’t any. Sons-in-law are a worry, dying as they do. Although not you, Maître d’Anton. I don’t intend it personally. You’re not a worry, I’m sure. You look quite healthy. In fact, excessively so.’

How can he be so dignified, d’Anton wondered, when his talk is so random and wild? Was he always like this, or had the situation made him so, and was it the Deficit that had unhinged him, or was it his domestic affairs?

‘And your dear wife?’ M. Charpentier inquired. ‘How is she?’

M. Duplessis brooded on this question; he looked as if he could not quite recall her face. At last he said, ‘Much the same.’

‘Won’t you come and have supper one evening? The girls too, of course, if they’d like to come?’

‘I would, you know … but the pressure of work … I’m a good deal at Versailles during the week now, it was only that today I had some business to attend to … sometimes I work through the weekend too.’ He turned to d’Anton. ‘I’ve been at the Treasury all my life. It’s been a rewarding career, but every day gets a little harder. If only the Abbé Terray …’

Charpentier stifled a yawn. He had heard it before; everyone had heard it. The Abbé Terray was Duplessis’s all-time Top Comptroller, his fiscal hero. ‘If Terray had stayed, he could have saved us; every scheme put forward in recent years, every solution, Terray had worked it out years ago.’ That had been when he was a younger man, and the girls were babies, and his work was something he looked forward to with a sense of the separate venture and progress of each day. But the Parlements had opposed the abbé; they had accused him of speculating in grain, and induced the silly people to burn him in effigy. ‘That was before the situation was so bad; the problems were manageable then. Since then I’ve seen them come along with the same old bright ideas –’ He made a gesture of despair. M. Duplessis cared most deeply about the state of the royal Treasury; and since the departure of the Abbé Terray his work had become a kind of daily official heartbreak.

M. Charpentier leaned forward to refill his cup. ‘No, I must be off,’ Duplessis said. ‘I’ve brought papers home. We’ll take you up on that invitation. Just as soon as the present crisis is over.’

M. Duplessis picked up his hat, bowed and nodded his way to the door. ‘When will it ever be over?’ Charpentier asked. ‘One can’t imagine.’

Angélique rustled up. ‘I saw you,’ she said. ‘You were distinctly grinning, when you asked him about his wife. And you,’ she slapped d’Anton lightly on the shoulder, ‘were turning quite blue trying not to laugh. What am I missing?’

‘Only gossip, my dear.’

‘Only gossip? What else is there in life?’

‘It concerns Georges’s gypsy friend, M. How-to-get-on-in-Society.’

‘What? Camille? You’re teasing me. You’re just saying this to test out my gullibility.’ She looked around at her smirking customers. ‘Annette Duplessis?’ she said. ‘Annette Duplessis?’

‘Listen carefully then,’ her husband said. ‘It’s complicated, it’s circumstantial, there’s no saying where it’s going to end. Some take season tickets to the Opéra; others enjoy the novels of Mr Fielding. Myself I enjoy a bit of home-grown entertainment, and I tell you, there’s nothing more entertaining than life at the rue Condé these days. For the connoisseur of human folly …’

‘Jesus-Maria! Get on with it,’ Angélique said.

II. Rue Condé: Thursday Afternoon

(1787)

ANNETTE DUPLESSIS was a woman of resource. The problem which now beset her she had handled elegantly for four years. This afternoon she was going to solve it. Since midday a chilly wind had blown up, draughts whistled through the apartment, finding out the keyholes and the cracks under the doors: fanning the nebulous banners of approaching crisis. Annette, thinking of her figure, took a glass of cider vinegar.

When she had married Claude Duplessis, a long time ago, he had been several years her senior; by now he was old enough to be her father. Why had she married him anyway? She often asked herself that. She could only conclude that she had been serious-minded as a girl, and had grown steadily more inclined to frivolity as the years passed.

At the time they met, Claude was working and worrying his way to the top of the civil service: through the different degrees and shades and variants of clerkdom, from clerk menial to clerk-of-some-parts, from intermediary clerk to clerk of a higher type, to clerk most senior, clerk confidential, clerk extraordinary, clerk in excelsis, clerk-to-end-all-clerks. His intelligence was the quality she noticed chiefly, and his steady, concerned application to the nation’s business. His father had been a blacksmith, and – although he was prosperous, and since before his son’s birth had not personally been anywhere near a forge – Claude’s professional success was a matter for admiration.

When his early struggles were over, and Claude was ready for marriage, he found himself awash in a dismaying sea of light-mindedness. She was the moneyed, sought-after girl on whom, for no reason one could see, he fixed his good opinion: on whom, at last, he settled his affection. The very disjunction between them seemed to say, here is some deep process at work; friends forecast a marriage that was out of the common run.

Claude did not say much, when he proposed. Figures were his medium. Anyway, she believed in emotions that ran too deep for words. His face and his hopes he kept very tightly strung, on stretched steel wires of self-control; she imagined his insecurities rattling about inside his head like the beads of an abacus.

Six months later her good intentions had perished of suffocation. One night she had run into the garden in her shift, crying out to the apple trees and the stars, ‘Claude, you are dull.’ She remembered the damp grass underfoot, and how she had shivered as she looked back at the lights of the house. She had sought marriage to be free from her parents’ constraints, but now she had given Claude her parole. You must never break gaol again, she told herself; it ends badly, dead bodies in muddy fields. She crept back inside, washed her feet; drank a warm tisane, to cure any lingering hopes.

Afterwards Claude had treated her with reserve and suspicion for some months. Even now, if she was unwell or whimsical, he would allude to the incident – explaining that he had learned to live with her unstable nature but that, when he was a young man, it had taken him quite by surprise.

After the girls were born there had been a small affair. He was a friend of her husband, a barrister, a square, blond man: last heard of in Toulouse, supporting a red-faced dropsical wife and five daughters at a convent school. She had not repeated the experiment. Claude had not found out about it. If he had, perhaps something would have had to change, but as he hadn’t – as he staunchly, wilfully, manfully hadn’t – there was no point in doing it again.

So then to hurry the years past – and to contemplate something that should not be thought of in the category of ‘an affair’ – Camille arrived in her life when he was twenty-two years old. Stanislas Fréron – her family knew his family – had brought him to the house. Camille looked perhaps seventeen. It was four years before he would be old enough to practise at the Bar. It was not a thing one could readily imagine. His conversation was a series of little sighs and hesitations, defections and demurs. Sometimes his hands shook. He had trouble looking anyone in the face.

He’s brilliant, Stanislas Fréron said. He’s going to be famous. Her presence, her household, seemed to terrify him. But he didn’t stay away.

RIGHT AT THE BEGINNING, Claude had invited him to supper. It was a well-chosen guest list, and for her husband a fine opportunity to expound his economic forecast for the next five years – grim – and to tell stories about the Abbé Terray. Camille sat in tense near-silence, occasionally asking in his soft voice for M. Duplessis to be more precise, to explain to him and to show him how he arrived at that figure. Claude called for pen, paper and ink. He pushed some plates aside and put his head down; at his end of the table, the meal came to a halt. The other guests looked down at them, nonplussed, and turned to each other with polite conversation. While Claude muttered and scribbled, Camille looked over his shoulder, disputing his simplifications, and asking questions that were longer and more cogent. Claude shut his eyes momentarily. Figures swooped and scattered from the end of his pen like starlings in the snow.

She had leaned across the table: ‘Darling, couldn’t you …’

‘One minute –’

‘If it’s so complicated –’

‘Here, you see, and here –’

‘ – talk about it afterwards?’

Claude flapped a balance sheet in the air. ‘Vaguely,’ he said. ‘No more than vaguely. But then the comptrollers are vague, and it gives you an idea.’

Camille took it from him and ran a glance over it; then he looked up, meeting her eyes. She was startled, shocked by the – emotion, she could only call it. She took her eyes away and rested them on other guests, solicitous for their comfort. What he basically didn’t understand, Camille said – and probably he was being very stupid – was the relationship of one ministry to another and how they all got their funds. No, Claude said, not stupid at all: might he demonstrate?

Claude now thrust back his chair and rose from his place at the head of the table. Her guests looked up. ‘We might all learn much, I am sure,’ said an under-secretary. But he looked dubious, very dubious, as Claude crossed the room. As he passed her, Annette put out a hand, as if to restrain a child. ‘I only want the fruit bowl,’ Claude said: as if it were reasonable.

When he had secured it he returned to his place and set it in the middle of the table. An orange jumped down and circumambulated slowly, as if sentient and tropically bound. All the guests watched it. His eyes on Claude’s face, Camille put out a hand and detained it. He gave it a gentle push, and slowly it rolled towards her across the table: entranced, she reached for it. All the guests watched her; she blushed faintly, as if she were fifteen. Her husband retrieved from a side-table the soup tureen. He snatched a dish of vegetables from a servant who was taking it away. ‘Let the fruit bowl represent revenue,’ he said.

Claude was the cynosure now; chit-chat ceased. If … Camille said; and but. ‘And let the soup tureen represent the Minister of Justice, who is also, of course, Keeper of the Seals.’

‘Claude –’ she said.

He shushed her. Fascinated, paralysed, the guests followed the movement of the food about the table; deftly, from the under-secretary’s finger ends, Claude removed his wine glass. This functionary now appeared, hand extended, as one who mimes a harpist at charades; his expression darkened, but Claude failed to see it.

‘Let us say, this salt cellar is the minister’s secretary.’

‘So much smaller,’ Camille marvelled. ‘I never knew they were so low.’

‘And these spoons, Treasury warrants. Now …’

Yes, Camille said, but would he clarify, would he explain, and could he just go back to where he said – yes indeed, Claude allowed, you need to get it straight in your mind. He reached for a water jug, to rectify the proportions; his face shone.

‘It’s better than the puppet show with Mr Punch,’ someone whispered.

‘Perhaps the tureen will talk in a squeaky voice soon.’

Let him have mercy, Annette prayed, please let him stop asking questions; with a little flourish here and one there she saw him orchestrating Claude, while her guests sat open-mouthed at the disarrayed board, their glasses empty or snatched away, deprived of their cutlery, gone without dessert, exchanging glances, bottling their mirth; all over town it will be told, ministry to ministry and at the Law Courts too, and people will dine out on the story of my dinner party. Please let him stop, she said, please something make it stop; but what could stop it? Perhaps, she thought, a small fire.

All the while, as she grew flurried, cast about her, as she swallowed a glass of wine and dabbed at her mouth with a handkerchief, Camille’s incendiary eyes scorched her over the flower arrangement. Finally with a nod of apology, and a placating smile that took in the voyeurs, she swept from the table and left the room. She sat for ten minutes at her dressing-table, shaken by the trend of her own thoughts. She meant to retouch her face, but not to see the hollow and lost expression in her eyes. It was some years since she and Claude had slept together; what relevance has it, why is she stopping to calculate it, should she also call for paper and ink and tot up the Deficit of her own life? Claude says that if this goes on till ’89 the country will have gone to the dogs and so will we all. In the mirror she sees herself, large blue eyes now swimming with unaccountable tears, which she instantly dabs away as earlier she dabbed red wine from her lips; perhaps I have drunk too much, perhaps we have all drunk too much, except that viperous boy, and whatever else the years give me cause to forgive him for I shall never forgive him for wrecking my party and making a fool of Claude. Why am I clutching this orange, she wondered. She stared down at her hand, like Lady Macbeth. What, in our house?

When she returned to her guests – the perfumed blood under her nails – the performance was over. The guests toyed with petits fours. Claude glanced up at her as if to ask where she had been. He looked cheerful. Camille had ceased to contribute to the conversation. He sat with his eyes cast down to the table. His expression, in one of her daughters, she would have called demure. All other faces wore an expression of dislocation and strain. Coffee was served: bitter and black, like chances missed.

NEXT DAY CLAUDE referred to these events. He said what a stimulating occasion it had been, so much better than the usual supper-party trivia. If all their social life were like that, he wouldn’t mind it so much, and so would she ask again that young man whose name for the present escaped him? He was so charming, so interested, and a shame about his stutter, but was he perhaps a little slow on the uptake? He hoped he had not carried away any wrong impressions about the workings of the Treasury.

How torturing, she thought, is the situation of fools who know they are fools; and how pleasant is Claude’s state, by comparison.

THE NEXT TIME Camille called, he was more discreet in the way he looked at her. It was as if they had reached an agreement that nothing should be precipitated. Interesting, she thought. Interesting.

He told her he did not want a legal career: but what else? He was trapped by the terms of his scholarship. Like Voltaire, he said, he wanted no profession but that of man of letters. ‘Oh, Voltaire,’ she said. ‘I’m sick of the name. Men of letters will be a luxury, let me tell you, in the years to come. We shall all have to work hard, with no diversions. We shall all have to emulate Claude.’ Camille pushed his hair back a fraction. That was a gesture she liked: rather representative, useless but winning. ‘You’re only saying that. You don’t believe it, in your heart. In your heart you think that things will go on as they are.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.