Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

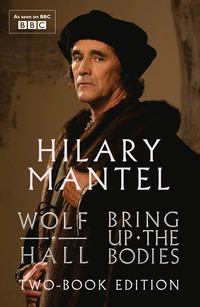

Kitabı oku: «Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies», sayfa 13

‘Did you want to talk about me?’ he asks. ‘You can do it while I’m here, Lord Chancellor. I have a thick skin.’ He knocks back a glass of wine and laughs. ‘Do you know what Brandon is saying? He can’t fit my life together. My travels. The other day he called me a Jewish peddler.’

‘And was that to your face?’ his host asks politely.

‘No. The king told me. But then my lord cardinal calls Brandon a horsekeeper.’

Humphrey Monmouth says, ‘You have the entrée these days, Thomas. And what do you think, now you are a courtier?’

There are smiles around the table. Because, of course, the idea is so ridiculous, the situation so temporary. More’s people are city people, no grander; but he is sui generis, a scholar and a wit. And More says, ‘Perhaps we should not press the point. There are delicate issues here. There is a time to be silent.’

An elder of the drapers’ guild leans across the table and warns, his voice low: ‘Thomas More said, when he took his seat, that he won’t discuss the cardinal, or the Lady either.’

He, Cromwell, looks around at the company. ‘The king surprises me, though. What he will tolerate.’

‘From you?’ More says.

‘I mean Brandon. They’re going to hunt: he walks in and shouts, are you ready?’

‘Your master the cardinal found it a constant battle,’ Bonvisi says, ‘in the early years of the reign. To stop the king’s companions becoming too familiar with him.’

‘He wanted only himself to be familiar,’ More suggests.

‘Though, of course, the king may raise up whom he will.’

‘Up to a point, Thomas,’ Bonvisi says; there is some laughter.

‘And the king enjoys his friendships. That is good, surely?’

‘A soft word, from you, Master Cromwell.’

‘Not at all,’ Monmouth says. ‘Master Cromwell is known as one who does everything for his friends.’

‘I think …’ More stops; he looks down at the table. ‘In all truth, I am not sure if one can regard a prince as a friend.’

‘But surely,’ Bonvisi says, ‘you’ve known Henry since he was a child.’

‘Yes, but friendship should be less exhausting … it should be restorative. Not like …’ More turns to him, for the first time, as if inviting comment. ‘I sometimes feel it is like … like Jacob wrestling with the angel.’

‘And who knows,’ he says, ‘what that fight was about?’

‘Yes, the text is silent. As with Cain and Abel. Who knows?’

He senses a little disquiet around the table, among the more pious, the less sportive; or just those keen for the next course. What will it be? Fish!

‘When you speak to Henry,’ More says, ‘I beg you, speak to the good heart. Not the strong will.’

He would pursue it, but the aged draper waves for more wine, and asks him, ‘How’s your friend Stephen Vaughan? What’s new in Antwerp?’ The conversation is about trade then; it is about shipping, interest rates; it is no more than a background hum to unruly speculation. If you come into a room and say, this is what we’re not talking about, it follows that you’re talking about nothing else. If the Lord Chancellor weren’t here it would be just import duties and bonded warehouses; we would not be thinking of the brooding scarlet cardinal, and our starved Lenten minds would not be occupied by the image of the king’s fingers creeping over a resistant, quick-breathing and virginal bosom. He leans back and fixes his gaze on Thomas More. In time there is a natural pause in conversation, a lull; and after a quarter-hour in which he has not spoken, the Lord Chancellor breaks into it, his voice low and angry, his eyes on the remnants of what he has eaten. ‘The Cardinal of York,’ he says, ‘has a greed that will never be appeased, for ruling over other men.’

‘Lord Chancellor,’ Bonvisi says, ‘you are looking at your herring as if you hate it.’

Says the gracious guest, ‘There’s nothing wrong with the herring.’

He leans forward, ready for this fight; he means not to let it pass. ‘The cardinal is a public man. So are you. Should he shrink from a public role?’

‘Yes.’ More looks up. ‘Yes, I think, a little, he should. A little less evident appetite, perhaps.’

‘It’s late,’ Monmouth says, ‘to read the cardinal a lesson in humility.’

‘His real friends have read it long ago, and been ignored.’

‘And you count yourself his friend?’ He sits back, arms folded. ‘I’ll tell him, Lord Chancellor, and by the blood of Christ he will find it a consolation, as he sits in exile and wonders why you have slandered him to the king.’

‘Gentlemen …’ Bonvisi rises in his chair, edgy.

‘No,’ he says, ‘sit down. Let’s have this straight. Thomas More here will tell you, I would have been a simple monk, but my father put me to the law. I would spend my life in church, if I had the choice. I am, as you know, indifferent to wealth. I am devoted to things of the spirit. The world’s esteem is nothing to me.’ He looks around the table. ‘So how did he become Lord Chancellor? Was it an accident?’

The doors open; Bonvisi jumps to his feet; relief floods his face. ‘Welcome, welcome,’ he says. ‘Gentlemen: the Emperor’s ambassador.’

It is Eustache Chapuys, come in with the desserts; the new ambassador, as one calls him, though he has been in post since fall. He stands poised on the threshold, so they may know him and admire: a little crooked man, in a doublet slashed and puffed, blue satin billowing through black; beneath it, his little black spindly legs. ‘I regret to be so late,’ he says. He simpers. ‘Les dépêches, toujours les dépêches.’

‘That’s the ambassador’s life.’ He looks up and smiles. ‘Thomas Cromwell.’

‘Ah, c’est le juif errant!’

At once the ambassador apologises: whilst smiling around, as if bemused, at the success of his joke.

Sit down, sit down, says Bonvisi, and the servants bustle, the cloths are swept away, the company rearranges itself more informally, except for the Lord Chancellor, who goes on sitting where he’s sitting. Preserved autumn fruits come in, and spiced wine, and Chapuys takes a place of honour beside More.

‘We will speak French, gentlemen,’ says Bonvisi.

French, as it happens, is the first language of the ambassador of the Empire and Spain; and like any other diplomat, he will never take the trouble to learn English, for how will that help him in his next posting? So kind, so kind, he says, as he eases himself back in the carved chair their host has vacated; his feet do not quite touch the floor. More rouses himself then; he and the ambassador put their heads together. He watches them; they glance back at him resentfully; but looking is free.

In a tiny moment when they pause, he cuts in. ‘Monsieur Chapuys? You know, I was talking with the king recently about those events, so regrettable, when your master’s troops plundered the Holy City. Perhaps you can advise us? We don’t understand them even now.’

Chapuys shakes his head. ‘Most regrettable events.’

‘Thomas More thinks it was the secret Mohammedans in your army who ran wild – oh, and my own people, of course, the wandering Jews. But before this, he has said it was the Germans, the Lutherans, who raped the poor virgins and desecrated the shrines. In all cases, as the Lord Chancellor says, the Emperor must blame himself; but to whom should we attach blame? Are you able to help us out?’

‘My dear Sir Chancellor!’ The ambassador is shocked. His eyes turn towards Thomas More. ‘Did you speak so, of my imperial master?’ A glance flicked over his shoulder, and he drops into Latin.

The company, linguistically agile, sit and smile at him. He advises, pleasantly, ‘If you wish to be half-secret, try Greek. Allez, Monsieur Chapuys, rattle away! The Lord Chancellor will understand you.’

The party breaks up soon after, the Lord Chancellor rising to go; but before he does, he makes a pronouncement to the company, in English. ‘Master Cromwell’s position,’ he says, ‘is indefensible, it seems to me. He is no friend to the church, as we all know, but he is friend to one priest. And that priest the most corrupt in Christendom.’

With the curtest of nods he takes his leave. Even Chapuys does not warrant more. The ambassador looks after him, dubious, biting his lip: as if to say, I looked for more help and friendship there. Everything Chapuys does, he notices, is like something an actor does. When he thinks, he casts his eyes down, places two fingers to his forehead. When he sorrows, he sighs. When he is perplexed, he wags his chin, he half-smiles. He is like a man who has wandered inadvertently into a play, who has found it to be a comedy, and decided to stay and see it through.

The supper is over; the company dwindle away, into the early dusk. ‘Perhaps sooner than you would have liked?’ he says, to Bonvisi.

‘Thomas More is my old friend. You should not come here and bait him.’

‘Oh, have I spoiled your party? You invited Monmouth; was that not to bait him?’

‘No, Humphrey Monmouth is my friend too.’

‘And I?’

‘Of course.’

They have slid back naturally into Italian. ‘Tell me something that intrigues me,’ he says. ‘I want to know about Thomas Wyatt.’ Wyatt went to Italy, having attached himself to a diplomatic mission, rather suddenly: three years ago now. He had a disastrous time there, but that’s for another evening; the question is, why did he run away from the English court in such haste?

‘Ah. Wyatt and Lady Anne,’ Bonvisi says. ‘An old story, I’d have thought?’

Well, perhaps, he says, but he tells him about the boy Mark, the musician, who seems sure Wyatt’s had her; if the story’s bouncing around Europe, among servants and menials, what are the odds the king hasn’t heard?

‘A part of the art of ruling, I suppose, is to know when to shut your ears. And Wyatt is handsome,’ Bonvisi says, ‘in the English style, of course. He is tall, he is blond, my countrymen marvel at him; where do you breed such people? And so assured, of course. And a poet!’

He laughs at his friend because, like all the Italians, he can’t say ‘Wyatt’: it comes out ‘Guiett’, or something like that. There was a man called Hawkwood, a knight of Essex, used to rape and burn and murder in Italy, in the days of chivalry; the Italians called him Acuto, The Needle.

‘Yes, but Anne …’ He senses, from his glimpses of her, that she is unlikely to be moved by anything so impermanent as beauty. ‘These few years she has needed a husband, more than anything: a name, an establishment, a place from which she can stand and negotiate with the king. Now, Wyatt’s married. What could he offer her?’

‘Verses?’ says the merchant. ‘It wasn’t diplomacy took him out of England. It was that she was torturing him. He no longer dared be in the same room with her. The same castle. The same country.’ He shakes his head. ‘Aren’t the English odd?’

‘Christ, aren’t they?’ he says.

‘You must take care. The Lady’s family, they are pushing a little against the limit of what can be done. They are saying, why wait for the Pope? Can we not make a marriage contract without him?’

‘It would seem to be the way forward.’

‘Try one of these sugared almonds.’

He smiles. Bonvisi says, ‘Tommaso, I may give you some advice? The cardinal is finished.’

‘Don’t be so sure.’

‘Yes, and if you did not love him, you would know it was true.’

‘The cardinal has been nothing but good to me.’

‘But he must go north.’

‘The world will chase him. You ask the ambassadors. Ask Chapuys. Ask them who they report to. We have them at Esher, at Richmond. Toujours les dépêches. That’s us.’

‘But that is what he is accused of! Running a country within the country!’

He sighs. ‘I know.’

‘And what will you do about it?’

‘Ask him to be more humble?’

Bonvisi laughs. ‘Ah, Thomas. Please, you know when he goes north you will be a man without a master. That is the point. You are seeing the king, but it is only for now, while he works out how to give the cardinal a pay-off that will keep him quiet. But then?’

He hesitates. ‘The king likes me.’

‘The king is an inconstant lover.’

‘Not to Anne.’

‘That is where I must warn you. Oh, not because of Guiett … not because of any gossip, any light thing said … but because it must all end soon … she will give way, she is just a woman … think how foolish a man would have been if he had linked his fortunes to those of the Lady’s sister, who came before her.’

‘Yes, just think.’

He looks around the room. That’s where the Lord Chancellor sat. On his left, the hungry merchants. On his right, the new ambassador. There, Humphrey Monmouth the heretic. There, Antonio Bonvisi. Here, Thomas Cromwell. And there are ghostly places set, for the Duke of Suffolk large and bland, for Norfolk jangling his holy medals and shouting ‘By the Mass!’ There is a place set for the king, and for the doughty little queen, famished in this penitential season, her belly quaking inside the stout armour of her robes. There is a place set for Lady Anne, glancing around with her restless black eyes, eating nothing, missing nothing, tugging at the pearls around her little neck. There is a place for William Tyndale, and one for the Pope; Clement looks at the candied quinces, too coarsely cut, and his Medici lip curls. And there sits Brother Martin Luther, greasy and fat: glowering at them all, and spitting out his fishbones.

A servant comes in. ‘Two young gentlemen are outside, master, asking for you by name.’

He looks up. ‘Yes?’

‘Master Richard Cromwell and Master Rafe. With servants from your household, waiting to take you home.’

He understands that the whole purpose of the evening has been to warn him: to warn him off. He will remember it, the fatal placement: if it proves fatal. That soft hiss and whisper, of stone destroying itself; that distant sound of walls sliding, of plaster crumbling, of rubble crashing on to fragile human skulls? That is the sound of the roof of Christendom, falling on the people below.

Bonvisi says, ‘You have a private army, Tommaso. I suppose you have to watch your back.’

‘You know I do.’ His glance sweeps the room: one last look. ‘Good night. It was a good supper. I liked the eels. Will you send your cook to see mine? I have a new sauce to brighten the season. One needs mace and ginger, some dried mint leaves chopped –’

His friend says, ‘I beg of you. I implore you to be careful.’

‘– a little, but a very little garlic –’

‘Wherever you dine next, pray do not –’

‘– and of breadcrumbs, a scant handful …’

‘– sit down with the Boleyns.’

II Entirely Beloved Cromwell Spring–December 1530

He arrives early at York Place. The baited gulls, penned in their keeping yards, are crying out to their free brothers on the river, who wheel screaming and diving over the palace walls. The carmen are pushing up from the river goods incoming, and the courts smell of baking bread. Some children are bringing fresh rushes, tied in bundles, and they greet him by name. For their civility, he gives each of them a coin, and they stop to talk. ‘So, you are going to the evil lady. She has bewitched the king, you know? Do you have a medal or a relic, master, to protect you?’

‘I had a medal. But I lost it.’

‘You should ask our cardinal,’ one child says. ‘He will give you another.’

The scent of the rushes is sharp and green; the morning is fine. The rooms of York Place are familiar to him, and as he passes through them towards the inner chambers he sees a half-familiar face and says, ‘Mark?’

The boy detaches himself from the wall where he is leaning. ‘You’re about early. How are you?’

A sulky shrug.

‘It must feel strange to be back here at York Place, now the world is so altered.’

‘No.’

‘You don’t miss my lord cardinal?’

‘No.’

‘You are happy?’

‘Yes.’

‘My lord will be pleased to know.’ To himself he says, as he moves away, you may never think of us, Mark, but we think of you. Or at least I do, I think of you calling me a felon and predicting my death. It is true that the cardinal always says, there are no safe places, there are no sealed rooms, you may as well stand on Cheapside shouting out your sins as confess to a priest anywhere in England. But when I spoke to the cardinal of killing, when I saw a shadow on the wall, there was no one to hear; so if Mark reckons I’m a murderer, that’s only because he thinks I look like one.

Eight anterooms: in the last, where the cardinal should be, he finds Anne Boleyn. Look, there are Solomon and Sheba, unrolled again, back on the wall. There is a draught; Sheba eddies towards him, rosy, round, and he acknowledges her: Anselma, lady made of wool, I thought I’d never see you again.

He had sent word back to Antwerp, applied discreetly for news; Anselma was married, Stephen Vaughan said, and to a younger man, a banker. So if he drowns or anything, he said, let me know. Vaughan writes back: Thomas, come now, isn’t England full of widows? And fresh young girls?

Sheba makes Anne look bad: sallow and sharp. She stands by the window, her fingers tugging and ripping at a sprig of rosemary. When she sees him, she drops it, and her hands dip back into her trailing sleeves.

In December, the king gave a banquet, to celebrate her father’s elevation to be Earl of Wiltshire. The queen was elsewhere, and Anne sat where Katherine should sit. There was frost on the ground, frost in the atmosphere. They only heard of it, in the Wolsey household. The Duchess of Norfolk (who is always furious about something) was furious that her niece should have precedence. The Duchess of Suffolk, Henry’s sister, refused to eat. Neither of these great ladies spoke to Boleyn’s daughter. Nevertheless, Anne had taken her place as the first lady of the kingdom.

But now it’s the end of Lent, and Henry has gone back to his wife; he hasn’t the face to be with his concubine as we move towards the week of Christ’s Passion. Her father is abroad, on diplomatic business; so is her brother George, now Lord Rochford; so is Thomas Wyatt, the poet whom she tortures. She’s alone and bored at York Place; and she’s reduced to sending for Thomas Cromwell, to see if he offers any amusement.

A flurry of little dogs – three of them – run away from her skirts, yapping, darting towards him. ‘Don’t let them out,’ Anne says, and with practised and gentle hands he scoops them up – they are the kind of dogs, Bellas, with ragged ears and tiny wafting tails, that any merchant’s wife would keep, across the Narrow Sea. By the time he has given them back to her, they have nibbled his fingers and his coat, licked his face and yearned towards him with goggling eyes: as if he were someone they had so much longed to meet.

Two of them he sets gently on the floor; the smallest he hands back to Anne. ‘Vous êtes gentil,’ she says, ‘and how my babies like you! I could not love, you know, those apes that Katherine keeps. Les singes enchaînés. Their little hands, their little necks fettered. My babies love me for myself.’

She’s so small. Her bones are so delicate, her waist so narrow; if two law students make one cardinal, two Annes make one Katherine. Various women are sitting on low stools, sewing or rather pretending to sew. One of them is Mary Boleyn. She keeps her head down, as well she might. One of them is Mary Shelton, a bold pink-and-white Boleyn cousin, who looks him over, and – quite obviously – says to herself, Mother of God, is that the best Lady Carey thought she could get? Back in the shadows there is another girl, who has her face turned away, trying to hide. He does not know who she is, but he understands why she’s looking fixedly at the floor. Anne seems to inspire it; now that he’s put the dogs down, he’s doing the same thing.

‘Alors,’ Anne says softly, ‘suddenly, everything is about you. The king does not cease to quote Master Cromwell.’ She pronounces it as if she can’t manage the English: Cremuel. ‘He is so right, he is at all points correct … Also, let us not forget, Maître Cremuel makes us laugh.’

‘I see the king does sometimes laugh. But you, madame? In your situation? As you find yourself?’

A black glance, over her shoulder. ‘I suppose I seldom. Laugh. If I think. But I had not thought.’

‘This is what your life has come to.’

Dusty fragments, dried leaves and stems, have fallen down her skirts. She stares out at the morning.

‘Let me put it this way,’ he says. ‘Since my lord cardinal was reduced, how much progress have you seen in your cause?’

‘None.’

‘No one knows the workings of Christian countries like my lord cardinal. No one is more intimate with kings. Think how bound to you he would be, Lady Anne, if you were the means of erasing these misunderstandings and restoring him to the king’s grace.’

She doesn’t answer.

‘Think,’ he says. ‘He is the only man in England who can obtain for you what you need.’

‘Very well. Make his case. You have five minutes.’

‘Otherwise, I can see you’re really busy.’

Anne looks at him with dislike, and speaks in French. ‘What do you know of how I occupy my hours?’

‘My lady, are we having this conversation in English or French? Your choice entirely. But let’s make it one or the other, yes?’

He sees a movement from the corner of his eye; the half-hidden girl has raised her face. She is plain and pale; she looks shocked.

‘You are indifferent?’ Anne says.

‘Yes.’

‘Very well. In French.’

He tells her again: the cardinal is the only man who can deliver a good verdict from the Pope. He is the only man who can deliver the king’s conscience, and deliver it clean.

She listens. He will say that for her. He has always wondered how well women can hear, beneath the muffling folds of their veils and hoods, but Anne does give the impression that she is hearing what he has said. She waits him out, at least; she doesn’t interrupt, until at last she does: so, she says, if the king wants it, and the cardinal wants it, he who was formerly the chief subject in the kingdom, then I must say, Master Cremuel, it is all taking a marvellous long while to come to pass!

From her corner her sister adds, barely audible, ‘And she’s not getting any younger.’

Not a stitch have the women added to their sewing since he has been in the room.

‘One may resume?’ he asks, persuading her. ‘There is a moment left?’

‘Oh yes,’ Anne says. ‘But a moment only: in Lent I ration my patience.’

He tells her to dismiss the slanderers who claim that the cardinal obstructed her cause. He tells her how it distresses the cardinal that the king should not have his heart’s desire, which was ever the cardinal’s desire too. He tells her how all the king’s subjects repose their hopes in her, for an heir to the throne; and how he is sure they are right to do so. He reminds her of the many gracious letters she has written to the cardinal in times past: all of which he has on file.

‘Very nice,’ she says, when he stops. ‘Very nice, Master Cremuel, but try again. One thing. One simple thing we asked of the cardinal, and he would not. One simple thing.’

‘You know it was not simple.’

‘Perhaps I am a simple person,’ Anne says. ‘Do you feel I am?’

‘You may be. I hardly know you.’

The reply incenses her. He sees her sister smirk. You may go, Anne says: and Mary jumps up, and follows him out.

Once again Mary’s cheeks are flushed, her lips are parted. She’s brought her sewing with her, which he thinks is strange; but perhaps, if she leaves it behind, Anne pulls the stitches out. ‘Out of breath again, Lady Carey?’

‘We thought she might run up and slap you. Will you come again? Shelton and I can’t wait.’

‘She can stand it,’ he says, and Mary says, indeed, she likes a skirmish with someone on her own level. What are you working there? he asks, and she shows him. It is Anne’s new coat of arms. On everything, I suppose, he says, and she smiles broadly, oh yes, her petticoats, her handkerchiefs, her coifs and her veils; she has garments that no one ever wore before, just so she can have her arms sewn on, not to mention the wall hangings, the table napkins …

‘And how are you?’

She looks down, glance swivelling away from him. ‘Worn down. Frayed a little, you might say. Christmas was …’

‘They quarrelled. So one hears.’

‘First he quarrelled with Katherine. Then he came here for sympathy. Anne said, what! I told you not to argue with Katherine, you know you always lose. If he were not a king,’ she says with relish, ‘one could pity him. For the dog’s life they lead him.’

‘There have been rumours that Anne –’

‘Yes, but she’s not. I would be the first to know. If she thickened by an inch, it would be me who let out her clothes. Besides, she can’t, because they don’t. They haven’t.’

‘She’d tell you?’

‘Of course – out of spite!’ Still Mary will not meet his eyes. But she seems to feel she owes him information. ‘When they are alone, she lets him unlace her bodice.’

‘At least he doesn’t call you to do it.’

‘He pulls down her shift and kisses her breasts.’

‘Good man if he can find them.’

Mary laughs; a boisterous, unsisterly laugh. It must be audible within, because almost at once the door opens and the small hiding girl manoeuvres herself around it. Her face is grave, her reserve complete; her skin is so fine that it is almost translucent. ‘Lady Carey,’ she says, ‘Lady Anne wants you.’

She speaks their names as if she is making introductions between two cockroaches.

Mary snaps, oh, by the saints! and turns on her heel, whipping her train behind her with the ease of long practice.

To his surprise, the small pale girl catches his glance; behind the retreating back of Mary Boleyn, she raises her own eyes to Heaven.

Walking away – eight antechambers back to the rest of his day – he knows that Anne has stepped forward to a place where he can see her, the morning light lying along the curve of her throat. He sees the thin arch of her eyebrow, her smile, the turn of her head on her long slender neck. He sees her speed, intelligence and rigour. He didn’t think she would help the cardinal, but what do you lose by asking? He thinks, it is the first proposition I have put to her; probably not the last.

There was a moment when Anne gave him all her attention: her skewering dark glance. The king, too, knows how to look; blue eyes, their mildness deceptive. Is this how they look at each other? Or in some other way? For a second he understands it; then he doesn’t. He stands by a window. A flock of starlings settles among the tight black buds of a bare tree. Then, like black buds unfolding, they open their wings; they flutter and sing, stirring everything into motion, air, wings, black notes in music. He becomes aware that he is watching them with pleasure: that something almost extinct, some small gesture towards the future, is ready to welcome the spring; in some spare, desperate way, he is looking forward to Easter, the end of Lenten fasting, the end of penitence. There is a world beyond this black world. There is a world of the possible. A world where Anne can be queen is a world where Cromwell can be Cromwell. He sees it; then he doesn’t. The moment is fleeting. But insight cannot be taken back. You cannot return to the moment you were in before.

In Lent, there are butchers who will sell you red meat, if you know where to go. At Austin Friars he goes down to talk to his kitchen staff, and says to his chief man, ‘The cardinal is sick, he is dispensed from Lent.’

His cook takes off his hat. ‘By the Pope?’

‘By me.’ He runs his eye along the row of knives in their racks, the cleavers for splitting bones. He picks one up, looks at its edge, decides it needs sharpening and says, ‘Do you think I look like a murderer? In your good opinion?’

A silence. After a while, Thurston proffers, ‘At this moment, master, I would have to say …’

‘No, but suppose I were making my way to Gray’s Inn … Can you picture to yourself? Carrying a folio of papers and an inkhorn?’

‘I do suppose a clerk would be carrying those.’

‘So you can’t picture it?’

Thurston takes off his hat again, and turns it inside out. He looks at it as if his brains might be inside it, or at least some prompt as to what to say next. ‘I see how you would look like a lawyer. Not like a murderer, no. But if you will forgive me, master, you always look like a man who knows how to cut up a carcase.’

He has the kitchen make beef olives for the cardinal, stuffed with sage and marjoram, neatly trussed and placed side by side in trays, so that the cooks at Richmond need do nothing but bake them. Show me where it says in the Bible, a man shall not eat beef olives in March.

He thinks of Lady Anne, her unslaked appetite for a fight; the sad ladies about her. He sends those ladies some flat baskets of small tarts, made of preserved oranges and honey. To Anne herself he sends a dish of almond cream. It is flavoured with rose-water and decorated with the preserved petals of roses, and with candied violets. He is above riding across the country, carrying food himself; but not that much above it. It’s not so many years since the Frescobaldi kitchen in Florence; or perhaps it is, but his memory is clear, exact. He was clarifying calf’s-foot jelly, chatting away in his mixture of French, Tuscan and Putney, when somebody shouted, ‘Tommaso, they want you upstairs.’ His movements were unhurried as he nodded to a kitchen child, who brought him a basin of water. He washed his hands, dried them on a linen cloth. He took off his apron and hung it on a peg. For all he knows, it is there still.

He saw a young boy – younger than him – on hands and knees, scrubbing the steps. He sang as he worked:

‘Scaramella va alla guerra Colla lancia et la rotella La zombero boro borombetta, La boro borombo …’

‘If you please, Giacomo,’ he said. To let him pass, the boy moved aside, into the curve of the wall. A shift of the light wiped the curiosity from his face, blanking it, fading his past into the past, washing the future clean. Scaramella is off to war … But I’ve been to war, he thought.