Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Roaring Girls», sayfa 2

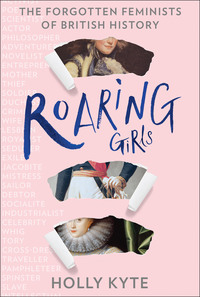

IS THIS WHAT A FEMINIST LOOKS LIKE?

The urge to label such extraordinary women from history as ‘feminists’ is almost irresistible. Naturally, we want to ‘think back through our mothers’, as Virginia Woolf phrased it,[17] and find inspiring heroines to admire; it’s our way of trying to bridge the gap between us, so we can all be on the same team. But to foist modern values and paradigms onto women who lived hundreds of years ago is to set ourselves a trap. If we take the dictionary definition of a feminist as one who supports ‘the advocacy of women’s rights on the ground of the equality of the sexes’,[18] the majority of the women in this book don’t qualify. Most would never have spared a thought for whether women should be granted equal rights with men – that was too big a question too soon, given the scale of the obstacles; they were usually far too busy trying to negotiate their own lives to worry about anyone else’s. The human rights that women enjoy today would have been met with stunned disbelief by these women, and the word ‘feminist’ with a blank stare.[19] The women’s suffrage movement was only just beginning to coalesce in the 1850s, so any woman who spoke out in defence of her sex before then was not a spoke in the wheel of any political or civil movement, buoyed by support from like-minded allies; she was a lone voice in a din of misogyny.

When examining the lives of historical women, there’s no ignoring that their world was not our world; they lived by a different set of standards, a lower bar of expectation, and to try to force our modern concept of feminism to fit retrospectively would be foolhardy. As such, our Roaring Girls don’t always behave in the ways we might want them to or say the things we want to hear. Many of them are a mass of contradictions. With their natural instincts so out of kilter with the social conventions of their day, the result was often paradoxical characters who were both products of their time and ahead of their time. To avoid disappointment, they should always be viewed against their own historical backdrop, rather than ours.

Which is why it can only ever be anachronistic to label these women simply as feminists. And yet, the spirit of feminism was not born with the word. There was no Damascene moment when the movement burst into being, fully formed and fully armed, like Athena sprouting from the head of Zeus. It didn’t arrive with the first Suffragists in the 1860s; it didn’t even arrive with Mary Wollstonecraft in the 1790s. Its birth was slow, incremental, painful and faltering, forged over centuries and across the world, by actions great and incidental, by people famous and forgotten.

What binds these women together, then, is not that they were feminists as we would understand them today, but that they all in some way broke the heavily gendered rules of what a woman ‘ought’ to be and began the work of rewriting them, exposing ignorance, reclaiming their freedoms and overturning preconceptions as they went. They may not have realised it, but that in itself was a feminist act. If we can allow ourselves to relax the remit of the word, we might call these formidable women a fraction of the many early feminists, proto-feminists, accidental, unwitting, even reluctant feminists, who, despite every effort to suppress them, dared to be extraordinary – who, between them, struck the first sparks of what would later become a blaze.

This book is intended as a celebration of these unconventional women’s lives, in all their messy, three-dimensional wonder, in the hope of affording them a little of the gratitude and recognition they so richly deserve, and reclaiming some of the complexity that has historically been denied them. It’s time we viewed such women not as saints or martyrs, heroes or villains, virgins or whores, masculine or feminine, but as real, contradictory, compelling human beings who laughed, loved, cried and fought their way through life, making the best of it, making mistakes – and each in their own way making history. Above all, it’s a collection of stories about courage – the courage of women who, in a world that constantly told them no, stood firm and roared back the word yes.

THE ROARING GIRL

It is Sunday, 9 February 1612, and a crowd has gathered in the churchyard of old St Paul’s Cathedral to see a woman punished. Her crime is against nature; she has disgraced all womankind with her monstrous acts, and now, before the public and before God, she must admit her shame and be cleansed of guilt.

Barefoot and bare-headed, the woman walks out into the wan morning light, swathed in a white sheet and clutching a long taper. For those who can read it, a placard proclaiming her sin hangs around her neck. As she makes her way unsteadily across the cold flagstones of the yard towards the pulpit and carefully climbs the steps to the platform, the jeers from the crowd rise up and follow her.

From the pulpit stage, she looks out over her audience and sees a swarm of eager faces. They are waiting for the show to start, so when the priest begins his sermon, the woman takes her cue. She drops her eyes, suppresses a smile and does her best to cry.

The woman was Mary Frith, and six weeks before, on Christmas Day 1611, she had been arrested (not for the first time) at St Paul’s

Cathedral for walking the streets of London at night dressed in men’s clothes. The result was a charge of public immorality, and a punishment designed to humiliate, disgrace and correct her: she would do public penance in a white sheet, at the open-air pulpit of St Paul’s Cross within the cathedral grounds,[1] where all could bear witness to her forced repentance and the purification of her soul.

This symbolic ritual was a tried and tested disciplinary measure, already centuries old by 1612, but in this instance, it was a waste of time. The ecclesiastical court, which dealt with all lapses in personal morality, was attempting to shame and reform a woman who would not be shamed or reformed, and in the end, the event was more farcical pantomime than solemn ceremony. The penitent herself, it was observed, regarded her punishment with such merry disdain that she was drunk throughout the proceedings; for her, it seems, this was just another opportunity to play to the crowds. Her priest’s sermon, meanwhile – a lengthy lecture denouncing her sin and calling on her to repent – was so mind-numbingly tedious that most of the audience lost interest and wandered off partway through. Those who stayed, however, were rewarded for their patience with precisely what they had come for: a free performance by ‘Moll Cutpurse’ – one of the most famous, and infamous, women in London.

THE THREE FACES OF MARY

When Mary Frith completed her act of penance at St Paul’s Cross in 1612, her name – or at least that of her alter ego, ‘Moll Cutpurse’ – had been on the lips of most Jacobean Londoners for several years, especially those who frequented the playhouses, taverns, brothels and bear pits of Bankside, the lawless entertainment district of Southwark that lay conveniently outside the City’s jurisdiction. Whether they loved or loathed her, feared or admired her, Mary’s notorious career as a cross-dressing thief (or ‘cutpurse’[2]) and street entertainer had fascinated the public, and by the time she’d reached her mid-twenties, she had achieved cult celebrity status – so much so that several playwrights had already appropriated, refashioned and immortalised her persona as a wholly unconventional folk heroine.

Fifty years later, Mary’s legend as one of the most enjoyably outrageous and controversial women of the age was still going strong, confirmed by the arrival in 1662 of a sensationalised ‘autobiography’, The Life and Death of Mrs Mary Frith, which, if it were what it pretends to be – the candid deathbed diary of a repentant sinner – would constitute an invaluable primary source for Mary’s life and an important early example of life writing by an Englishwoman. As it is, the diary is almost certainly a fake. There is no credible evidence that Mary wrote it herself; after all, she’d been dead for three years before it appeared, and although up to 50 per cent of women in London were literate by the late seventeenth century (a much higher proportion than in most parts of the country), it’s unlikely that a woman of low birth such as Mary would have been one of them.[3]

The book’s numerous factual errors and omissions point instead to another hand, and given its erratic style, maybe even several. Falling into three distinct and sometimes contradictory sections – an opening address, an introduction summarising Mary’s upbringing and a ‘diary’ of her life as a cutpurse – it comprises a string of unapologetic, entertaining, though often disjointed, anecdotes of her misdeeds, and seems to have more in common with the fictionalised criminal biographies that were popular at the time than it does with a genuine diary,[4] veering in tone from comic to defiant to political and even preachy.

This ‘diary’, then, is an unreliable account of Mary’s life, though that’s not to say it’s worthless. Plenty of the details within its pages chime with what we know to be true. It’s plausible that the authors had their anecdotes either directly from Mary when she was alive – an old woman entertaining anyone in the alehouse who would listen with tales of her outrageous youth – or from those who knew her, or, more likely, that they adapted them from the tales of her exploits that had been passed from gossip to gossip for decades. Mary had already written herself into London’s folklore with her riotous escapades, leaving the diary’s anonymous authors the task of matching, if not surpassing, these outlandish oral tales.

But herein lies the problem with Mary Frith. With the historical records frustratingly reticent on her real life (her appearances in them are few, though always revealing), much of what we know – or think we know – of her comes from the various fictionalised versions that appeared over the years, making her as slippery a character in death as she was in life. The legend who features in the ‘diary’, the character who walked the stage and the flesh-and-blood woman who left an imprint on the records don’t always agree, splitting her image into hazy triplicate. The diarists were aware of the issue. Their excuse for the ‘abruptness and discontinuance’ of their story is that ‘it was impossible to make one piece of so various a subject’.[5] This isn’t just an unwitting admission of their own fudged documentation of her life; evidently Mary’s baffling complexity made her as intangible to her contemporaries as she is to us.

Lower-class, lawless, unconventional and disobedient, Mary Frith was disturbing – but also strangely alluring; she represented an unusual kind of woman in the seventeenth century, one to whom society had no answer. By definition, such women lived a precarious life and needed cunning strategies to survive, and in Mary’s case that meant barricading herself in behind a protective wall of myth and mystique, cultivating multiple personalities and perfecting her performance of each one until the real woman became as elusive as wisps of smoke. With so many Marys before us, it’s as if she’s laid down a challenge: to find the real Mary Frith, and catch her if we can.

A VERY TOMRIG OR RUMPSCUTTLE

The mystery authors of The Life and Death of Mrs Mary Frith do their best to get to the bottom of this unfathomable woman, but she is ‘so difficult a mixture’ of male and female, of ‘dishonesty and fair and civil deportment’, that they seem torn from the start between admiration and alarm. Faced with a cross-dressing thief who on the one hand must surely be morally reprehensible, but on the other was famed for her good humour and entertaining shenanigans, they delight in her one minute, sneer at her the next – sometimes all at once. Their introduction showers Mary with mock-heroic epithets: she is ‘a prodigy’, an ‘epicoene wonder’, ‘the oracle of felony’, the gold-standard bearer of thievery – a profession that is now in ‘sad decays’ without her; but she is also a ‘virago’, a ‘bono roba’ (prostitute), a monstrous hybrid of masculine and feminine, so unattractive that she was ‘not made for the pleasure or delight of man’. Such a woman made little sense to her peers; she was as much a side-show freak as she was a folkloric heroine, and needed to be explained to the uncomprehending but fascinated public.

In their attempt to do just that, the authors begin at the beginning, with Mary’s childhood, which, if the bare bones of their introduction are to be believed, served as a dress rehearsal for the role she would play in later life. With an air of surprise, they report that this natural rebel was born to perfectly ordinary, law-abiding parents – an ‘honest shoemaker’ and his wife, who lived in the Barbican area of London – in the latter years of Elizabeth I’s reign (the exact year is unclear). Tender, affectionate and indulgent, Mr and Mrs Frith offered their daughter a humble upbringing, though a happy and stable one.[6] By rights, she ought to have been just another honest, hard-working young woman who soon married and settled into her predetermined roles of wife and mother. But no.

Mary’s ‘boisterous and masculine spirit’ manifested itself early and would not be tamed. To curb her unruly ways, we’re told that her parents took particular care over her education (which by the standards of the day meant teaching her to read but not to write, as well as a few domestic accomplishments), but their efforts had little effect. Young Mary was a child of action, not academia. She was an archetypal tomboy – ‘a very tomrig or rumpscuttle’ – fizzing with energy, and resistant to every norm of female behaviour: she would ‘fight with boys, and courageously beat them’; ‘run, jump, leap or hop with any of them’, and ravage her pretty girls’ clothes in the scuffles. She didn’t care – her dresses hung awkwardly on her ungainly frame and only annoyed her.

Drawn to the places where the rabble congregated, this scrappy urchin spent most of her time at the Bear Garden, the rowdy entertainment arena wedged in among the playhouses of Bankside, where bear-baiting, bull-baiting and dog fighting kept the blood-lusty crowds amused. Here, in the fug of the bustling, stinking, noisy Southwark streets, all the vices were out on display: drunks and tavern brawlers, punters and prostitutes, cutpurses and cheats jostled along together, while down the road, above the gateway of old London Bridge, the heads of traitors sat on spikes, like gruesome lollipops in a sweet-shop window. Young Mary saw it all, and she wasn’t fazed in the least; in fact, she fitted right in.

However unladylike, this was the world where Mary Frith felt at home, for she was ‘too great a libertine … to be enclosed in the limits of a private domestic life’. As womanhood approached, she showed no interest in the feminine pursuits she was expected to learn: ‘she could not endure that sedentary life of sewing or stitching’, preferring a sword and a dagger to a needle and thimble. The bakehouse and the laundry were alien to her, and the ‘magpie chat of the wenches’ an irritation. Mary preferred a more direct form of expression. Even when she was young she was ‘not for mincing obscenity’; by adulthood, the habit had developed into ‘downright swearing’. Such profane language from a woman was unfeminine and unacceptable and, along with the rest of her behaviour, it had to be policed (as Mary would later discover – her reputed potty mouth would be listed in the court records as one of her many arrestable offences). To complete this picture of the ultimate anti-woman, we’re told that ‘above all she had a natural abhorrence to the tending of children’, and steered well clear of becoming a mother (another claim that is borne out by the records).

If this character portrait is accurate, Mary was a woman destined to offend and perplex seventeenth-century society in every way. Indeed, so far was she from the meek, mild, modest woman that custom demanded that it was doubted she was a woman at all. She had unsexed herself, become a ‘hermaphrodite in manners as well as in habit’; she was ‘the living description of a schism and separation’, combining the ‘female subtlety’ of one sex and the ‘manly resolution’ of the other – and to a society that only dealt in strict gender binaries, such a combination was profoundly unnerving.

A lower-class girl with no money, little education and scant opportunities had very few options in life even if she conformed, but if, like Mary, she either would not or could not conform, the choice was almost made for her. Such girls often found themselves tripping over into the wrong side of the law in order to survive, usually through thievery or prostitution, but even in that world there was a hierarchy to climb. If Mary wanted to live differently to most women, she would have to behave differently to most women. And if she wanted a modicum of the power and freedom that men had, then she would have to settle for power and freedom in the criminal underworld.

MOLL CUTPURSE

Too proud to beg, too wild for domestic drudgery and quite possibly too repulsed by men to contemplate prostitution, Mary Frith decided to make her living as a cutpurse. It was the most dangerous choice of all these unappealing options, for to embark upon a career of thievery automatically meant risking her liberty and her life. England in the early seventeenth century was a visibly savage place: legal punishments were reliably disproportionate to the crime and barbaric public executions were a favoured form of entertainment. With property deemed as valuable as human life – and frequently even more so – theft and burglary were among the country’s capital offences; if Mary’s fingers weren’t quite nimble enough, she could be facing a stint in Newgate Gaol, or worse, the drop at Tyburn.[7] But in a city where ostentatious wealth rubbed shoulders with grinding poverty, the temptation to pick the glittering pockets of affluent bankers, merchants, lawyers and lords was just too great. Undeterred, or perhaps just desperate, Mary joined the hordes of cutpurses who plagued Elizabethan London early – probably when she was still a child – and quickly demonstrated a knack for getting away with it.

Undoubtedly it played to her advantage that law and order was then a haphazard thing – the professional police force had yet to be established and certain areas, including Mary’s stomping ground of Southwark, fell outside the City’s jurisdiction, making them attractive dens for every kind of vice. These areas were more or less governed by underground criminal networks. Magistrates relied on local volunteer constables to keep the peace and apprehend criminals, who in turn relied on members of the public to raise a ‘hue and cry’ whenever they spotted a misdemeanour. Mary was presumably so adept at sleight of hand that she mostly managed to pilfer unnoticed, though she wasn’t always so lucky.

The records show that on 26 August 1600, when she was still a teenager, she was first charged by the Justices of Middlesex with stealing an unknown man’s purse, while working in cahoots with two other women. She wriggled out of it on this occasion but was indicted again on 18 March 1602 for stealing a purse from a man named Richard Ingles, and again on 8 September 1609, for burglary.[8] Every time, she managed to secure a verdict of not guilty and escape a trip to Newgate – or the noose – so that by her early twenties she had made quite a career for herself. And with it came a well-earned new nickname: ‘Moll Cutpurse’.[9]

The details of Mary’s subsequent life as a cutpurse are filled in by The Life and Death of Mrs Mary Frith with unashamed glee. After a short preamble, Mary’s so-called ‘diary’ embarks on a chain of anecdotes about her many misadventures, tricks and petty revenges, even providing a kind of instruction manual in places on how she and her colleagues successfully plied their trade. Helpful details such as dates are absent, and psychological self-analysis doesn’t trouble her – ‘It is no matter to know how I grew up to this,’ she states dismissively, ‘since I have laid it as a maxim that it was my fate.’ She is, however, allowed the odd moment of reflection when it’s to marvel at what an extraordinary creature she is. ‘I do more wonder at myself than others can do,’ she declares in awe, with the same air of amusement with which she relates all of her history. For the purpose here, more than anything, is to entertain with her oddity. Accordingly, her crimes are softened to ‘pranks’ and, like her literary descendant Moll Flanders, she is portrayed as an honest thief and magnetic heroine, her maxim for life: ‘To be excellent and happy in villainy’, because that has always been ‘reputed equal with a good fame’.

Judging by these anecdotes, Mary’s good fame was justified. She tells of being tricked into boarding a ship for the plantations of Virginia and her subsequent escape by paying off the captain, and of how, being poor and friendless, she then joined a gang of pickpockets, who judged her to be ‘very well qualified for a receiver and entertainer of their fortunate achievements’ – or rather a receiver of stolen goods. This was a life she rather took to, for although the danger was evident, she was ‘loath to relinquish the profit’, and seems to have quickly established a unique and powerful position for herself as protectress and confidante of this coterie of thieves. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement. Being ‘well known to all the gang, and by my good dealing with them not a little in their favour’, Mary was offered protection and anonymity in return – a real case of honour among thieves. She would share out the profits fairly, act as ‘umpire in their quarrels’ and lend money to the most desperate, thereby preventing them from committing dangerous robberies and effectively saving them from ‘the hangman’s clutches’. By fashioning herself as the fair, magnanimous champion of lowlifes in this way, Mary earned the respect and devoted loyalty of her fellow cutpurses, ‘so that among all the thieveries they did, my name was never heard of; for they made it the chiefest of their religion to conceal me and to conceal nothing of their designs from me’. In effect, she had negotiated her way to the top of her own organised crime ring – and secured her own immunity in the process.

It was a wily strategy, though not foolproof – as we know, Mary occasionally found herself in hot water, but when she did, the pickpocket community was allegedly swift to come to her rescue. In one instance, cited in the diary, when Mary is taken up for stealing a watch, she employs one of her gang to commit the ultimate theft in front of a packed courtroom, purely to get her off the hook. Once she had pleaded not guilty, she says, ‘it came to this issue, whether that watch for which I was indicted was the gentleman’s watch or no’. The constable who had apprehended her was called forward to deliver the watch for the gentleman to identify, but just as the constable was making his way into court, Mary deployed her secret weapon: ‘one of my small officers dived into his pocket and sought out the evidence against me, and departed invisible’.

This neat trick naturally incensed the Lord Mayor, who immediately suspected her chicanery, but with no evidence to hand, there was nothing he could do. Once again, the jury were forced to acquit Mary, leaving her free to continue with her shady dealings, undiscouraged and irredeemable as ever. Before long, she tells us, she had the confidence of famous highwaymen, too, and begins to cut a figure rather like a seventeenth-century Fagin, sending off her gang of pickpockets and robbers to do their light-fingered work and bring back the spoils to their mistress.

It’s not known exactly when Mary Frith began to combine her pickpocketing with transvestism, but it seems likely to have coincided with the advent of her entertainment career – a male-dominated industry like all the others – when she was in her early twenties.

Counterintuitive though this decision seems for a thief whose life depended on anonymity, in around 1608 Mary began to see the advantage in developing her persona as ‘Moll Cutpurse’ into a public attraction; by simply donning a doublet, hat and cloak, she could become a ‘character’, who simultaneously drew the crowds to her and distanced her from them. It soon become her signature. Dressed in men’s clothes, she would walk the streets of Southwark, challenging ‘diverse gallants’ to sartorial competitions and entertaining the crowds with her ‘mad pranks’, while her gang of footpads weaved through the distracted audience, cutting purses as they went. Now a decoy as well as a fence and low-level criminal mastermind, Mary Frith had pulled off a protean magic trick: she had become Moll Cutpurse, the charming, eccentric rogue who could never be caught in the act.

Mary’s transvestism was unusual, but it didn’t occur in isolation. It was part of a Europe-wide underground trend for female cross-dressing that first sprang up in the 1570s, reached a peak in the 1620s, thrived throughout the eighteenth century and continued on into the early nineteenth, when it rapidly fizzled out. The UK was particularly prone to this phenomenon, having one of the highest incidence rates in Europe – there are at least 50 recorded cases during this period of women living as men, either to work, marry or serve their country as soldiers and sailors – and it’s easy to see the appeal.[10] A woman’s clothes were ornamental rather than practical, designed to hinder, not help her. Her rigid stays and voluminous skirts accentuated her primary functions of mother and sex object, and were as cumbersome and restrictive as the social rules that bound her. To throw them off in favour of a doublet and hose offered a long list of symbolic attractions. For some women, sidestepping the arbitrary trappings of gender was a survival strategy or simple expedient, a handy disguise when in trouble, in love or going off to war. For others, it was an expression of their complex sexuality, which, in an era before sexual categorisation, had only a one-size-fits-all model. For many more, it meant safety – from harassment, seduction, rape and prostitution, from forced marriages and unwanted pregnancy. And for the ambitious or adventurous, who, as Mary Beard puts it, had ‘no template for what a powerful woman looks like, except that she looks rather like a man’,[11] it meant a sudden open door to agency and opportunity. For those who dabbled, it was pleasingly provocative. For those who went the whole hog, it was a liberation. For all of them, it was a direct challenge to the intractable social codes that governed everyone’s lives – an early feminist act of defiance.[12]

To a country that had long employed sartorial sumptuary laws to scrupulously to preserve the distinctions of rank in its citizens, this trend for female transvestism indicated their alarming lack of control over the distinctions of gender. The Bible had decried cross-dressing as an ‘abomination unto the Lord’,[13] a subversion of the ‘proper’ hierarchy between woman, man and God, as the pamphleteer Phillip Stubbes was keen to remind everybody in his 1583 Anatomy of Abuses. All cross-dressers, he wrote, were ‘accursed’. Men who did it were ‘weak, tender and infirm’, degrading themselves to the status of feeble, powerless females.[14] Women who did it were hermaphroditic ‘monsters’ and presumptuous whores, attempting to steal a man’s power and usurp his sovereignty.

It was this perceived power exchange that was key to transvestism’s ability to unsettle and enrage society. In women, not only did it smack of insubordination, but with its elements of disguise, evasion and masculine aggression, it carried an intrinsic connection to both criminality and sexual incontinency. In 1615, a fencing master named Joseph Swetnam was so incensed by this fad that Mary Frith was spearheading that he published The Arraignment of Lewd, Idle, Froward, and Unconstant Women – a misogynist’s rant in which he bloviated against the ‘heinous evils’ of women. The book was so popular it went through ten editions by 1637, and the concerns it spoke of went right to the very top. King James I, another notorious misogynist, voiced his own anxieties in January 1620, when he commanded that the clergy ‘inveigh vehemently and bitterly in their sermons, against the insolence of our women’ for ‘their wearing of broad brimmed hats’ and ‘pointed doublets’, for having ‘their hair cut short or shorne’ and for carrying ‘stilettoes or poinards [daggers]’.[15] His decree then sparked a pamphlet war the following month between the anonymous authors of Hic Mulier, or, The Man-Woman and Haec Vir; or, The Womanish Man, who publicly fought out the big question: where these ‘masculine-feminines’ a monstrous ‘deformity never before dreamed of’, or emancipated slaves fighting for freedom of choice and self-expression?[16] It could not have been clearer that, even after decades of furiously debating the controversy, this new breed of woman that Mary represented encapsulated men’s fears that ‘the world is very far out of order’.[17]

Consequently, and perhaps inevitably, the panicked authorities frantically cracked down on this destabilising wave of transvestism in an attempt to stamp it out. Several women are known to have been arrested and punished for it long before Mary took it up: in 1569, one Joanna Goodman was whipped and sent to the Bridewell house of correction for dressing as a male servant to accompany her husband to war; in July 1575, the Aldermen’s Court sentenced Dorothy Clayton to stand on the pillory for two hours before sending her to Bridewell Prison and Hospital because ‘contrary to all honesty and womanhood [she] commonly goes about the City apparelled in man’s attire’; in 1599, Katherine Cuffe was sent to Bridewell for disguising herself in boy’s clothes to meet her lover in secret, as was Margaret Wakeley in 1601, because she ‘had a bastard child and went in men’s apparel’.[18]