Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography»

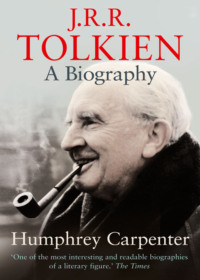

J.R.R. TOLKIEN

A BIOGRAPHY

HUMPHREY CARPENTER

Dedicated to the memory of ‘The T.C.B.S.’

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Part One

A VISIT

PART TWO: 1892–1916: Early years

CHAPTER I: BLOEMFONTEIN

CHAPTER II: BIRMINGHAM

CHAPTER III: ‘PRIVATE LANG.’ – AND EDITH

CHAPTER IV: ‘T.C, B.S., ETC.’

CHAPTER V: OXFORD

CHAPTER VI: REUNION

CHAPTER VII: WAR

CHAPTER VIII: THE BREAKING OF THE FELLOWSHIP

PART THREE: 1917–1925: The making of a mythology

CHAPTER I: LOST TALES

CHAPTER II: OXFORD INTERLUDE

CHAPTER III: NORTHERN VENTURE

PART FOUR: 1925–1949(i):‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit’

CHAPTER I: OXFORD LIFE

CHAPTER II: PHOTOGRAPHS OBSERVED

CHAPTER III: ‘HE HAD BEEN INSIDE LANGUAGE’

CHAPTER IV: JACK

Additional Images

CHAPTER V: NORTHMOOR ROAD

CHAPTER VI: THE STORYTELLER

PART FIVE : 1925–1949(ii): The Third Age

CHAPTER I : ENTER MR BAGGINS

CHAPTER II: ‘THE NEW HOBBIT’

PART SIX : 1949–1966: Success

CHAPTER I : SLAMMING THE GATES

CHAPTER II : A BIG RISK

CHAPTER III: CASH OR KUDOS

PART SEVEN: 1959–1973: Last years

CHAPTER I: HEADINGTON

CHAPTER II: BOURNEMOUTH

CHAPTER III: MERTON STREET

POSTSCRIPT: THE TREE

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX C

APPENDIX D

INDEX

About the Author

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ALSO BY HUMPHREY CARPENTER

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part One

A VISIT

It is mid-morning on a spring day in 1967. I have driven from the centre of Oxford, over Magdalen Bridge, along the London road, and up a hill into the respectable but dull suburb of Headington. Near a large private school for girls I turn left into Sandfield Road, a residential street of two-storey brick houses, each with its tidy front garden.

Number seventy-six is a long way down the road. The house is painted white and is partially screened by a tall fence, a hedge, and overhanging trees. I park the car, open the arched gate, go up the short path between rose bushes, and ring the front door bell.

For a long time there is silence, except for the rumble of distant traffic in the main road. I am beginning to think of ringing again or of turning away when the door is opened by Professor Tolkien.

He is slightly smaller than I expected. Tallness is a quality of which he makes much in his books, so it is a little surprising to see that he himself is slightly less than the average height – not much, but just enough to be noticeable. I introduce myself, and (since I made this appointment in advance and am expected) the quizzical and somewhat defensive look that first met me is replaced by a smile. A hand is offered and my own is firmly grasped.

Behind him I can see the entrance-hall, which is small and tidy and contains nothing that one would not expect in the house of a middle-class elderly couple. W. H. Auden, in an injudicious remark quoted in the newspapers, has called the house ‘hideous’, but that is nonsense. It is simply ordinary and suburban.

Mrs Tolkien appears for a moment, to greet me. She is smaller than her husband, a neat old lady with white hair bound close to her head, and dark eyebrows. Pleasantries are exchanged, and then the Professor comes out of the front door and takes me into his ‘office’ at the side of the house.

This proves to be the garage, long abandoned by any car – he explains that he has not had a car since the beginning of the Second World War – and, since his retirement, made habitable and given over to the housing of books and papers formerly kept in his college room. The shelves are crammed with dictionaries, works on etymology and philology, and editions of texts in many languages, predominant among which are Old and Middle English and Old Norse; but there is also a section devoted to translations of The Lord of the Rings into Polish, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, and Japanese; and the map of his invented ‘Middle-earth’ is pinned to the window-ledge. On the floor is a very old portmanteau full of letters, and on the desk are ink-bottles, nibs and pen-holders, and two typewriters. The room smells of books and tobacco smoke.

It is not very comfortable, and the Professor apologises for receiving me here, but he explains that there is no space in the study-bedroom in the house where he actually does his writing. He says that in any case this is all temporary: soon he will, he hopes manage to finish at least the major part of the work promised to his publishers, and then he and Mrs Tolkien will be able to move to more comfortable quarters and congenial surroundings, away from visitors and intrusions. He looks slightly embarrassed after the last remark.

I climb past the electric fire and, at his bidding, seat myself in a wheel-back chair, as he takes his pipe from the pocket of his tweed jacket and launches into an explanation of his inability to spare me more than a few minutes. A shiny blue alarm clock ticks noisily across the room as if to emphasise the point. He says that he has to clear up an apparent contradiction in a passage of The Lord of the Rings that has been pointed out in a letter from a reader; the matter requires his urgent consideration as a revised edition of the book is about to go to press. He explains it all in great detail, talking about his book not as a work of fiction but as a chronicle of actual events; he seems to see himself not as an author who has made a slight error that must now be corrected or explained away, but as a historian who must cast light on an obscurity in a historical document.

Disconcertingly, he seems to think that I know the book as well as he does. I have read it many times, but he is talking about details that mean little or nothing to me. I begin to fear that he will throw some penetrating question at me that will reveal my ignorance – and indeed now he does ask me a question, but fortunately it is rhetorical and clearly requires no more than the answer ‘yes’.

I am still nervous that there will be other and harder questions, doubly nervous because I cannot hear everything that he is saying. He has a strange voice, deep but without resonance, entirely English but with some quality in it that I cannot define, as if he had come from another age or civilisation. Yet for much of the time he does not speak clearly. Words come out in eager rushes. Whole phrases are elided or compressed in the haste of emphasis. Often his hand comes up and grasps his mouth, which makes it even harder to hear him. He speaks in complex sentences, scarcely hesitating – but then there comes a long pause in which I am surely expected to reply. Reply to what? If there was a question, I did not understand it. Suddenly he resumes (never having finished his sentence) and now he reaches an emphatic conclusion. As he does so, he jams his pipe between his teeth, speaks on through clenched jaws, and strikes a match just as the full stop is reached.

Again I struggle to think of an intelligent remark, and again he resumes before I can find one. Following some slender connecting thread, he begins to talk about a remark in a newspaper that has made him angry. Now I feel that I can contribute a little, and I say something that I hope sounds intelligent. He listens with courteous interest, and answers me at some length, turning my remark (which was really very trivial) to excellent use, and so making me feel that I have said something worth saying. Then he is off on some tangential topic, and I am once more out of my depth, able to contribute no more than a monosyllable of agreement here and there; though it does occur to me that I am perhaps valued just as much as a listener as a participant in the conversation.

As he talks he moves unceasingly, pacing about the dark little room with an energy that hints at restlessness. He waves his pipe in the air, knocks it out in an ashtray, fills it, strikes a match, but scarcely ever smokes for more than a few puffs. He has small, neat, wrinkled hands, with a plain wedding-ring on the third finger of the left hand. His clothes are a little rumpled, but they sit well on him, and though he is in his seventy-sixth year there is only a suggestion of tubbiness behind the buttons of his coloured waistcoat. I cannot for long keep my attention from his eyes, which may wander about the room or stare out of the window, yet now and then will return to dart a glance at me or rest a steady gaze as some vital point is made. They are surrounded by wrinkles and folds that change with and emphasise each mood.

The flood of words has dried up for a moment and the pipe is being lit again. I perceive my opportunity, and state my business, which now seems unimportant. Yet he turns to it immediately with enthusiasm, and listens to me attentively. Then, when this part of the conversation is done, I get up to go; but for the moment my departure is evidently neither expected nor desired, for he has started to talk again. Once more he refers to his own mythology. His eyes fix on some distant object, and he seems to have forgotten that I am there as he clutches his pipe and speaks through its stem. It occurs to me that in all externals he resembles the archetypal Oxford don, at times even the stage caricature of a don. But that is exactly what he is not. It is rather as if some strange spirit had taken on the guise of an elderly professor. The body may be pacing this shabby little suburban room, but the mind is far away, roaming the plains and mountains of Middle-earth.

Then it is all over, and I am being ushered out of the garage and taken to the garden gate – the smaller one opposite the front door: he explains that he has to keep the garage gates padlocked to stop football spectators parking their cars in his drive when they attend matches at the local stadium. Rather to my surprise, he asks me to come and see him again. Not for the moment, as neither he nor Mrs Tolkien has been well, and they are going on holiday to Bournemouth, and his work is many years behind-hand, and letters are piling up unanswered. But some time, soon. He shakes my hand and is gone, a little forlornly, back into the house.

PART TWO 1892–1916: Early years

CHAPTER 1 BLOEMFONTEIN

On a March day in 1891 the steamer Roslin Castle left dock to sail from England to the Cape. Standing on the stern deck, waving to the family she would not see again for a long time, was a slim good-looking girl of twenty-one. Mabel Suffield was going to South Africa to marry Arthur Tolkien.

It was in every way a dividing point in her life. Behind her lay Birmingham, foggy days, and family teas. Ahead was an unknown country, eternal sunshine, and marriage to a man thirteen years her senior.

Although Mabel was so young, there had been a long engagement, for Arthur Tolkien had proposed to her and she had accepted three years earlier, soon after her eighteenth birthday. However, her father would not permit a formal betrothal for two years because of her youth, and so she and Arthur could only exchange letters in secret and meet at evening parties where the family eye was upon them. The letters were entrusted by Mabel to her younger sister Jane, who would pass them to Arthur on the platform of New Street Station in Birmingham, when she was catching a train home from school to the suburb where the Suffields lived. The evening parties were generally musical gatherings at which Arthur and Mabel could only exchange covert glances or at most the touch of a sleeve, while his sisters played the piano.

It was a Tolkien piano, of course, one of the upright models manufactured by the family firm that had made what money the Tolkiens once possessed. On the lid was inscribed: ‘Irresistible Piano-Forte: Manufactured Expressly for Extreme Climates’; but the piano firm was in other hands now, and Arthur’s father was bankrupt, without a family business to provide employment for his sons. Arthur had tried to make a career in Lloyds Bank, but promotion in the Birmingham office was slow, and he knew that if he was to support a wife and family he would have to look elsewhere. He turned his eye to South Africa, where the gold and diamond discoveries were making banking into an expanding business with good prospects for employees. Less than a year after proposing to Mabel he had obtained a post with the Bank of Africa, and had sailed for the Cape.

Arthur’s initiative had soon been justified. For the first year he had been obliged to travel extensively, for he was sent on temporary postings to many of the principal towns between the Cape and Johannesburg. He acquitted himself well, and at the end of 1890 he was appointed manager of the important branch at Bloemfontein, capital of the Orange Free State. A house was provided for him, the income was adequate, and so at last marriage was possible. Mabel celebrated her twenty-first birthday at the end of January 1891, and only a few weeks later she was on board Roslin Castle and sailing towards South Africa and Arthur, their betrothal now blessed with her father’s approval.

Or perhaps ‘tolerance’ would be a better word, for John Suffield was a proud man, especially in the matter of ancestry which in many ways was all he had left to be proud of. Once he had owned a prosperous drapery business in Birmingham, but now like Arthur Tolkien’s father he was bankrupt. He had to earn his living as a commercial traveller for Jeyes disinfectant; yet the failure of his fortunes had only strengthened his pride in the old and respectable Midland family from which he was descended. What were the Tolkiens in comparison? Mere German immigrants, English by only a few generations – scarcely a fit pedigree for his daughter’s husband.

If such reflections occupied Mabel during her three-week voyage, they were far from her mind on the day early in April when the ship sailed into harbour at Cape Town, and she caught sight at last of a white-suited, handsome, and luxuriantly-moustached figure on the quay, scarcely looking his thirty-four years as he peered anxiously through the crowd for a glimpse of his darling ‘Mab’.

Arthur Reuel Tolkien and Mabel Suffield were married in Cape Town Cathedral on 16 April 1891, and spent their honeymoon in a hotel at nearby Sea Point. Then came an exhausting railway journey of nearly seven hundred miles to the capital of the Orange Free State, and the house which was to be Mabel’s first and only home with Arthur.

Bloemfontein had begun life forty-five years earlier as a mere hamlet. Even by 1891 it was of no great size. Certainly it did not present an impressive spectacle to Mabel as she and Arthur got off the train at the newly built railway station. In the centre of the town was the market square where the Dutch-speaking farmers from the veldt trundled in aboard great ox-wagons to unload and sell the bales of wool that were the backbone of the State’s economy. Around the square were clustered solid indications of civilisation: the colonnaded Parliament House, the two-towered Dutch Reformed church, the Anglican cathedral, the hospital, the public library, and the Presidency. There was a club for European residents (German, Dutch, and English), a tennis club, a law court, and a sufficiency of shops. But the trees that had been planted by the first settlers were still sparse, and the town’s park was, as Mabel observed, no more than about ten willows and a patch of water. Only a few hundred yards beyond the houses was the open veldt where wolves, wild dogs, and jackals roamed and menaced the flocks, and where after dark a post-rider might be attacked by a marauding lion. From these treeless plains the wind blew into Bloemfontein, stirring the dust of the broad dirt-covered streets. Mabel, writing to her family, summed up the town as ‘Owlin’ Wilderness! Horrid Waste!’

However for Arthur’s sake she must learn to like it, and meanwhile the life she found herself leading was by no means uncomfortable. The premises of the Bank of Africa, in Maitland Street just off the market square, included a solidly built residence with a large garden. There were servants in the house, some black or coloured, some white immigrants; and there was company enough to be chosen from among the many other English-speaking residents, who organised a regular if predictable round of dances and dinner-parties. Mabel had much time to herself, for when Arthur was not busy in the bank he was attending classes to learn Dutch, the language in which all government and legal documents were worded; or he was making useful acquaintances in the club. He could not afford to take life easy, for although there was only one other bank in Bloemfontein, this was the National, native to the Orange Free State; whereas the Bank of Africa of which Arthur was manager was an outsider, a uitlander, and was only tolerated by a special parliamentary decree. To make matters worse, the previous manager of the Bank of Africa had gone over to the National, and Arthur had to work doubly hard to make sure that valuable accounts did not follow him. Then there were new projects in the locality which might be turned to the advantage of his bank, schemes connected with the Kimberley diamonds to the west or the Witwatersrand gold to the north. It was a crucial stage in Arthur’s career, and, moreover, Mabel could see that he was intensely happy. His health had not been consistently good since he arrived in South Africa, but the climate seemed to suit his temperament; seemed, as Mabel noticed with the faintest apprehension, positively to appeal to him, whereas after only a few months she herself came to dislike it heartily. The oppressively hot summer and the cold, dry, dusty winter tried her nerves far more than she liked to admit to Arthur, and ‘home leave’ seemed a very long way off, for they would not be entitled to visit England until they had been in Bloemfontein for another three years.

Yet she adored Arthur, and she was always happy when she could entice him from his desk and they could go for walks or drives, play a game of tennis or a round of golf, or read aloud to each other. Soon there was something else to occupy her mind: the realisation that she was pregnant.

On 4 January 1892 Arthur Tolkien wrote home to Birmingham:

My dear Mother.

I have good news for you this week. Mabel gave me a beautiful little son last night (3 January). It was rather before time, but the baby is strong and well and Mabel has come through wonderfully. The baby is (of course) lovely. It has beautiful hands and ears (very long fingers) very light hair, ‘Tolkien’ eyes and very distinctly a ‘Suffield’ mouth. In general effect immensely like a very fair edition of its Aunt Mabel Mitton. When we first fetched Dr Stollreither yesterday he said it was a false alarm and told the nurse to go home for a fortnight but he was mistaken and I fetched him again about eight and then he stayed till 12.40 when we had a whisky to drink luck to the boy. The boy’s first name will be ‘John’ after its grandfather, probably John Ronald Reuel altogether. Mab wants to call it Ronald and I want to keep up John and Reuel…

‘Reuel’ was Arthur’s own second name, but there was no family precedent for ‘Ronald’. This was the name by which Arthur and Mabel came to address their son, the name that would be used by his relatives and later by his wife. Yet he sometimes said that he did not feel it to be his real name; indeed people seemed to feel faintly uncomfortable when choosing how to address him. A few close school-friends called him ‘John Ronald’, which sounded grand and euphonious. When he was an adult his intimates referred to him (as was customary at the time) by his surname, or called him ‘Tollers’, a hearty nickname typical of the period. To those not so close, especially in his later years, he was often known as ‘J.R.R.T.’ Perhaps in the end it was those four initials that seemed the best representation of the man.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was christened in Bloemfontein Cathedral on 31 January 1892, and some months later he had his photograph taken in the garden of Bank House, in the arms of the nurse who had been engaged to look after him. His mother was clearly in excellent health, while Arthur, always something of a dandy, posed in a positively jaunty manner in his white tropical suit and boater. Behind stood two black servants, a maid and a house-boy named Isaak, both looking pleased and a little surprised to be included in the photograph. Mabel found the Boer attitude to the natives objectionable, and in Bank House there was tolerance, most notably over the extraordinary behaviour of Isaak, who one day stole little John Ronald Reuel and took him to his kraal where he showed off with pride the novelty of a white baby. It upset everybody and caused a great turmoil, but Isaak was not dismissed, and in gratitude to his employer he named his own son ‘Isaak Mister Tolkien Victor’, the last being in honour of Queen Victoria.

There were other disturbances in the Tolkien household. One day a neighbour’s pet monkeys climbed over the wall and chewed up three of the baby’s pinafores. Snakes lurked in the wood-shed and had to be avoided. And many months later, when Ronald was beginning to walk, he stumbled on a tarantula. It bit him, and he ran in terror across the garden until the nurse snatched him up and sucked out the poison. When he grew up he could remember a hot day and running in fear through long, dead grass, but the memory of the tarantula itself faded, and he said that the incident left him with no especial dislike of spiders. Nevertheless, in his stories he wrote more than once of monstrous spiders with venomous bites.

For the most part life at Bank House maintained an orderly pattern. In the early morning and late afternoon the child would be taken into the garden, where he could watch his father tending the vines or planting saplings in a piece of walled but unused ground. During the first year of the boy’s life Arthur Tolkien made a small grove of cypresses, firs, and cedars. Perhaps this had something to do with the deep love of trees that would develop in Ronald.

From half past nine to half past four the child had to remain indoors, out of the blaze of the sun. Even in the house the heat could be intense, and he had to be clothed entirely in white. ‘Baby does look such a fairy when he’s very much dressed-up in white frills and white shoes,’ Mabel wrote to her husband’s mother. ‘When he’s very much undressed I think he looks more of an elf still.’

There was more company for Mabel now. Soon after the baby’s first birthday, her sister and brother-in-law May and Walter Incledon arrived from England. Walter, a Birmingham merchant in his early thirties, had business interests in the South African gold and diamond mines, and he left May and their small daughter Marjorie at Bank House and travelled on to the mining areas. May Incledon had arrived in time to keep her sister cheerful through the bitterness of another wintry summer in Bloemfontein, a season more hard to bear because Arthur too was away for some weeks on business. It was intensely cold, and the two sisters huddled around the dining-room stove while Mabel knitted garments for the baby and she and May talked about Birmingham days. Mabel was making little secret of her irritation with Bloemfontein life, its climate, its endless social calls, and its tedious dinner-parties. Home leave could be taken soon now, in a year or so – though Arthur was always suggesting reasons for postponing their visit to England. ‘I will not let him put it off too long,’ wrote Mabel. ‘He does grow too fond of this climate to please me. I wish I could like it better, as I’m sure he’ll never settle in England again.’

In the end the trip had to be postponed. Mabel found that she was pregnant again, and on 17 February 1894 she gave birth to another son. He was christened Hilary Arthur Reuel.

Hilary proved to be a healthy child who flourished in the Bloemfontein climate, but his elder brother was not doing so well. Ronald was sturdy and handsome, with his fair hair and blue eyes – ‘quite a young Saxon’, his father called him. By now he was talking volubly and entertaining the bank clerks on his daily visit to his father’s office downstairs, where he would demand pencil and paper and scribble away at crude drawings. But teething upset him badly and made him feverish, so that the doctor had to be called in day after day and Mabel was soon worn out. The weather was at its worst: an intense drought arrived, ruined trade, spoilt tempers, and brought a plague of locusts that swarmed across the veldt and destroyed a fine harvest. Yet despite all this, Arthur wrote to his father the words that Mabel had dreaded to hear: ‘I think I shall do well in this country and do not think I should settle down well in England again for a permanency.’

Whether they were to stay or not, it was clear that the heat was doing a great deal of harm to Ronald’s health. Something must be done to get him to cooler air. So in November 1894 Mabel took the two boys the many hundreds of miles to the coast near Cape Town. Ronald was nearly three now, old enough to retain a faint memory of the long train journey and of running back from the sea to a bathing hut on a wide flat sandy shore. After this holiday Mabel and the children returned to Bloemfontein, and preparations were made for their visit to England. Arthur had booked a passage and had engaged a nurse to travel with them. He badly wanted to accompany them himself; but he could not afford to be away from his desk, for there were railway schemes on hand that concerned the bank, and as he wrote to his father: ‘In these days of competition one does not like to leave one’s business in the hands of others.’ Moreover time spent away would be on half pay, and he could not easily afford this in addition to the expense of the voyage. So he decided to stay in Bloemfontein for the time being and to join his wife and children in England a little later. Ronald watched his father painting A. R. Tolkien on the lid of a family trunk. It was the only clear memory of him that the boy retained.

The S.S. Guelph carried Mabel and the boys from South Africa at the beginning of April 1895. In Ronald’s mind there would remain no more than a few words of Afrikaans and a faint recollection of a dry dusty barren landscape, while Hilary was too young even to remember this. Three weeks later, Mabel’s little sister Jane, now a grown woman, met them at Southampton; and in a few hours they were all in Birmingham and cramming into the tiny family house in King’s Heath. Mabel’s father was as jolly as ever, cracking jokes and making dreadful puns, and her mother was kind and understanding. They stayed on, and the spring and summer passed with a marked improvement in Ronald’s health; but though Arthur wrote to say that he missed his wife and children very badly and was longing to come and join them, there was always something to detain him.

Then in November came the news that he had contracted rheumatic fever. He had already partially recovered, but he could not face an English winter and would have to regain his health before he could make the journey. Mabel spent a desperately anxious Christmas, though Ronald enjoyed himself and was fascinated by the sight of his first Christmas tree, which was very different from the wilting eucalyptus that had adorned Bank House the previous December.

When January came, Arthur was reported to be still in poor health, and Mabel decided that she must go back to Bloemfontein and care for him. Arrangements were made, and an excited Ronald dictated a letter to his father which was written out by the nurse.

9 Ashfield Road, King’s Heath, February 14th 1896.

My dear Daddy,

I am so glad I am coming back to see you it is such a long time since we came away from you I hope the ship will bring us all back to you Mamie and Baby and me. I know you will be so glad to have a letter from your little Ronald it is such a long time since I wrote to you I am got such a big man now because I have got a man’s coat and a man’s bodice Mamie says you will not know Baby or me we have got such big men we have got such a lot of Christmas presents to show you Auntie Gracie has been to see us I walk every day and only ride in my mailcart a little bit. Hilary sends lots of love and kisses and so does your loving

Ronald.

This letter was never sent, for a telegram arrived to say that Arthur had suffered a severe haemorrhage and Mabel must expect the worst. Next day, 15 February 1896, he was dead. By the time a full account of his last hours had reached his widow, his body had been buried in the Anglican graveyard at Bloemfontein, five thousand miles from Birmingham.