Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

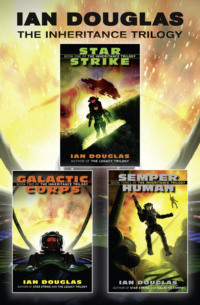

Kitabı oku: «The Complete Inheritance Trilogy: Star Strike, Galactic Corps, Semper Human», sayfa 8

Married Enlisted Housing

USMC Recruit Training Center

Noctis Labyrinthus, Mars

1924/24:20 local time, 0620 hrs GMT

Gunnery Sergeant Warhurst stepped out of the flyer and onto the landing deck outside his home. It was a small place, but with lots of exterior spaces and enclosed garden patios surrounding a double plasdome growing from a canyon wall. Other base housing modules were visible up and down the canyon, extruded from the ancient sandstone walls.

A billion years ago, this part of Mars had been under a sea a kilometer deep; the relentless rise of the Tharsis Bulge, however, had lifted the Noctis Labyrinthus high and dry; as the water drained away, it had carved the maze of channels from the soft stone. The northern ocean had rolled again, briefly, under the touch of the Builders half a million years ago, but by that time the Noctis Labyrinthus was far above mean sea level.

Apparently, the Builders had not colonized this part of Mars, restricting their activities to Cydonia, far to the north, to Chryse Planitia, and to Utopia on the far side of the planet. Some of the base personnel spent off hours pacing up and down the canyon with metal detectors, however. A handful of people out here had made fortunes with the chance find of a fragment of cast-off xenotech.

Warhurst never bothered with that sort of thing, however. His career—the Corps—was everything.

A fact that was making things difficult at home.

“Honey?” He stepped in off the deck, dropping his cover on a table. “I’m home.”

The place seemed empty, and he queried the house AI. “Where is everybody?”

Julie and Eric are home, the house’s voice whispered in his mind. Donal and Callie are still at the base.

Warhurst was part of a group marriage and, as was increasingly the case nowadays, all of the other partners in the relationship were also Marines. It was simpler that way … and the partners tended to be more understanding than civilians. Usually.

A door hissed open and Julie emerged from the bedroom. She was naked, and she looked angry. “Well, well. The prodigal is home. Decided to come visit the family for a change?”

“Don’t start, Julie.”

“Don’t start what?”

“Look, I know I haven’t been home much lately—”

“I know that too.” She ran a hand through her short hair. “Look, Marine, I’m having sex with Eric, so give us some privacy. Fix yourself dinner. When Don and Cal get home, we need to talk, the five of us.”

“What do you—”

But she’d already turned away and padded back into the bedroom.

Damn.

It had been a few days since he’d come home. How long? He pulled a quick check of his personal calendar, and saw the answer. Eight days.

Damn it, Julie knew the score. When a new recruit company started up, he spent all of his time with the company, at least for the first few weeks. After that, he shared the duty with the other DIs, sleeping in the DI shack, or in one of the senior NCO quads across the grinder one night out of four. But even late in the training regime, there were particular times when it was important that he be there. This past week had been the last week for the recruits of 4102 in naked time, without their civilian headware, a time when lots of them came close to cracking. He needed to be there, to see them through. He’d almost stayed over tonight as well, but Corrolly had insisted that he and Amanate could handle things.

He wished he’d stayed.

Julie’s flat statement about a family meeting probably meant an ultimatum, and that probably meant a formal request that he move back into the BOQ, the Bachelor Officers’ Quarters.

In other words, a divorce.

It had been coming for a long time. He knew she’d been wanting to talk to him about the marriage, and his part in it, for a long time, but he’d been hoping to postpone it, at least until after 4102 had graduated. Damn it, he didn’t have time for this nonsense, for all this sturm und drang, and Julie ought to know that. He didn’t have the emotional stamina to deal with it now, either. There was just too much on his plate. Angry, he walked into the kitchen unit and punched up a meal.

Warhurst was the most recent addition to the Tamalyn-Danner line marriage, having been invited in by Julie just fifteen months ago. Like many Corps weddings taking place on Mars, the vows had been declared, posted, and celebrated at Garroway Hall, at Cydonia, and half of RTC command had attended.

Marriages outside the Corps were discouraged. Not forbidden … but discouraged. A Marine might be at any given duty station for a year or two, but then he or she might be deployed across a hundred light-years, or end up on board a Navy ship plying a slow run between stargates. The routine played merry hell with traditional relationships.

At that, it was better than in the bad old days, before FTL and stargates, when a 4.3 light-year hop to Chiron took five and a half years objective, which meant a couple of years subjective spent in cybe-hibe stasis. Back then, Marines were assigned on the basis of their famsits, their family situations—whether or not they were married, had parents or other close relatives, and how closely tied they were psychologically to the Motherworld.

Long ago, the Corps had adopted the habit of assigning command staff as discrete groups, called command constellations, to avoid breaking up good working teams through transfers and redeployments. A similar set of regulations now governed marital relationships. While the Corps couldn’t promise to keep everyone in the family together—especially in group marriages that might number ten or more people—the AIs overseeing deployments did their best, even shuffling personnel from one MarDiv to another, when necessary, to make the numbers come out even. The tough part was when kids were involved. Each major base had its own crèche, nurseries, and schools, but Navy ships on deep survey or remote listening outposts at the fringes of known Xul systems didn’t have the resources for that kind of luxury. Those assignments still required Marines with Famsits of two or better.

What none of this took into account was the workload at established bases like Noctis-L. Training a company of raw recruits, breaking them out of their smug little civilian molds and building Marines out of what was left—that was a full-time job, and then some. Warhurst and five assistant DIs supervised Company 4102, now down to just forty-three recruits, and still it was never enough.

He closed his eyes. That one kid, Collins. After six weeks without her implants, she’d just … snapped. The messy and very public suicide had hit everyone hard, and the DI staff especially had been badly stressed. Damn it, he should have been there. …

Warhurst leaned back in his chair, his meal half finished but unwanted. He summoned a cup of coffee, though, and waited while a servo extended it to him from a nearby wall-mar. He knew there was nothing he could have done, and the board of inquiry had almost routinely absolved him and his staff of blame. But … he should have been there. Collins had stolen that thermite grenade one evening from a malfunctioning training arms locker when he’d been here, at home.

Angrily, he pushed the thought aside, then mentally clocked on the wallscreen, looking for the evening news. He wanted an external distraction, rather than an internal feed, telling himself he needed to keep his internal channels clear, in case there was a call from the base.

Which was pure theriashit, and he knew it. An emergency call would override any feed he had going. And either Achilles, the company AI, or Hector, who was reserved for the training staff, could talk to him at any time. He was avoiding the real issue, which was the strain within his marriage.

Damned right I’m avoiding it, he thought. And a good job I’m doing of it, too.

The news was dominated by the war, of course. The capture of Alighan was being hailed in the Senate as the defining victory of the war, the victory that would bring the Theocrats to their senses and bring them to the conference table.

“In other military news,” the announcer said, her three-meter-tall face filling the wall, “the Interstellar News Web have received an as yet unconfirmed report of hostile contact with what may be a Xul huntership outside of the Humankind Frontier. If true, this will be the first contact with the Xul in over 550 years.

“For this report, we go livefeed to Ian Castriani at Marine Corps Skybase headquarters in paraspace. Ian?”

The announcer’s face faded away, replaced by a young man standing in the Public Arena of the headquarters station. He looked intense, determined, and excited.

And what he had to say brought a cold, churning lump to the pit of Warhurst’s gut.

7

2410.1102

Marine Listening Post

Puller 659 Stargate

1554 hrs GMT

Lieutenant Tera Lee unlinked from the feed and blinked in the dim light of the comdome. “Shit,” she said, and made a face. “Shit!”

“What’s the problem, sweetheart?” Lieutenant Gerard Fitzpatrick, her partner on the watch, asked.

She ignored the familiarity. Fitzie was a jerk, but a reasonably well meaning one. She hadn’t had to deck him yet. Yet. …

“That’s four transgate drones we’ve lost contact with in the past ten minutes,” she said, checking the main board, then rechecking the communications web for a fault. Everything on this side of the Gate was working perfectly. “Something’s going down over there. I don’t like it.”

“You link through to the old man?”

“Chesty’s doing that now,” she told him. She wrinkled her nose. “I smell another sneakover.”

“Yeah, well, it’s your turn,” he said, shrugging. Then he brightened. “Unless you wanna—”

“Fuck you, Fitzie,” she said, keeping her voice light.

“Exactly.”

“Forget it, Marine. I have standards.”

He sighed theatrically. “You wound me, sweetheart.”

“Call me ‘sweetheart’ again and you’ll know what being wounded is like, jerkface. If you survive.”

She dropped back into the linknet before he could make another rejoinder.

The star system known to Marine Intelligence as Puller 659 was about as nondescript as star systems could get—a cool, red dwarf sun orbited by half a dozen rock-and-ice worlds scarcely worthy of the name, and a single Neptune-sized gas giant. The French astronomers who’d catalogued the system had named the world Anneau, meaning Ring, and the red dwarf Étoile d’Anneau, Ringstar. None of Ringstar’s planets possessed native life or showed signs of ever having been life-bearing. And despite frequent sweeps, no one had ever found any xenoarcheological tidbits, none whatsoever, save one.

And that one was why the Marine listening post was here. As Lee linked through to another teleoperated probe, she could see it in the background—a vast, gold-silver ring resembling a wedding band out of ancient tradition, but twenty kilometers across.

Just who or what had created the Stargates remained one of the great unanswered riddles of xenoarcheological research. Most academics, striving for the simplest possible view of things, assumed that the Builders—that long-vanished federation of starfaring civilizations half a million years ago—had created them, but there was no proof of that. It was equally likely that the things were millions of years old, that they’d been old already when the Builders had first come on the scene … back about the same time that the brightest creature on Earth was a clever tool-user that someday would receive the name Homo erectus.

Whoever or whatever had built the things evidently had scattered them across the entire Galaxy. Gates were known to exist in systems outside the Galactic plane; Night’s Edge was such a place, where the sweep of the Galaxy’s spiral arms filled half the sky. Gate connected Gate in a network still neither understood nor mapped. Each Gate possessed a pair of Jupiter-massed black holes rotating in opposite directions at close to the speed of light; shifting tidal stresses set up by the counter-rotating masses opened navigable pathways from one Gate to another, allowing passage across tens of thousands of light-years in an eye’s blink. More, the vibrational frequencies of those planetary masses could be tuned, allowing one Gate to connect with any of several thousand alternate Gates.

The alien N’mah, first contacted in 2170, had been living inside the Gate discovered in the Sirius system, 8.6 light-years from Earth. Though they’d lost the technology required for faster-than-light drives, they’d learned a little about Gate technology, and they’d taught Humankind how to use the Gates—at least after a fashion. Thanks to them, Marines had scored important victories over the Xul, in Cluster Space, and at Night’s Edge.

If it had simply been a matter of destroying Stargates to keep the Xul out of human space, things would have been far simpler. Unfortunately, it turned out that there was more than one way to outpace light. The Xul used the Gates extensively—indeed, a large minority of those academics felt that the Xul were the original builders of the Stargates—but their hunterships could also slip from star to star in days or weeks without benefit of the Gates.

In the past five centuries, Humans had learned at last how to harness quantum-state vacuum energies and liberate inconceivable free energy, and how to apply that energy to the Quantum Sea in order to achieve trans-c pseudovelocities—high multiples of the speed of light. They’d located some dozens of separate Stargates, and sent both robotic and manned probes through to chart the accessible spaces on the far side.

Most probes found only another Stargate, usually circling a distant star, like Puller 659, with lifeless worlds or no worlds at all. A few led to planetary systems possessing earthlike worlds, though, so far, no other sentient species had been found this way, and, in accord with the Treaty of Chiron, none had been opened to human colonization.

A very few, mercifully few, opened into star systems occupied by the Xul.

The Ringstar Gate at Puller 659 was one such. One of the regions accessed through the Puller Gate was in a system dominated by a hot, type A star, seething with deadly radiation burning off the galactic core, and host to a major Xul base.

As was the case every time a Xul base was discovered, a Marine listening post had been constructed close by the Puller 659 Gate, and a careful watch kept. Periodically, AI-controlled probes were sent through the Gate to record signals and images from the Xul base. The probes were tiny—the size of volleyballs—and virtually undetectable. The probes would slip through, make their recordings, then double back through the Gate to make their reports.

The usual routine was to send one probe through at a time, to minimize the chances of the reconnaissance being detected. Faults and failures happened, however, and losing contact with one or even two was not unusual, especially through the turbulent gravitic storms and tides swirling about the mouth of a Gate. But Lee had just sent the third probe in a row through to check on number one, and its lasercom trace—kept tight and low-power to avoid detection—had been cut off within twenty seconds of passing the Gate interface.

Not good. Not good at all … especially since the lasercom threads carried no data about what was going on down range, save that the probe was functional.

And standing orders described in considerable detail what happened in such cases.

It was time for a sneak-and-peek.

“Package up the log,” she told Chesty over the telencephalic link. “Beam it out NL. And recommend to Major Tomanaga that we go on full alert.”

“Major Tomanaga is already doing so,” the base AI told her, “and he has just authorized a level-2 reconnaissance through to Starwall.”

“Excellent.” Starwall was the name of the system on the other side of the Gate, the location of the Xul base.

“Will you be taking an FR-100 through the interface?”

“Yeah. Prep one for me, please.”

“Number Three is coming on-line now.”

In a larger base, there would have been a standby pool of Marine fighter pilots ready to fly recon, but the listening post was manned by six Marines at a time, standing watch-in-three. The main base complex was a space station orbiting the system’s gas giant, camouflaged from detection by the planet’s far-flung radiation belts and now almost two light-hours away. Non-local com webs bridged that gulf instantly, but it would be hours before fighters could get here.

Marine listening posts like Puller 659 were deliberately kept tiny and unobtrusive; Fitzie was right, damn him. It was her turn.

She dropped out of the link and rose from her couch. Leaving Fitzpatrick in his commlink couch at the monitor station, she caught an intrastation pod and dropped to the fighter bay, two decks down. The uniform of the day was Class-One VS, a black skinsuit that served as her vacsuit in a depressurization emergency, so she needed only to pick up a helmet, gloves, and LS pack on the way.

Her FR-100 Night Owl was warmed and ready for her when she arrived.

The Night Owl was dead black, pulling at the eye, a flat, smooth ovoid with teardrop sponsons and swellings for drives and sensor equipment, its sleek hull designed to absorb or safely redirect everything on the EM spectrum from long-wave radar to short-wave x-rays. It was sophisticated enough to fly itself without a human at the controls, but Corps doctrine still emphasized the need for a human at the controls in any situation where things might go suddenly and catastrophically wrong. The craft was tiny—three fluidly streamlined meters, with a cockpit barely large enough to receive her vacsuited body as it folded itself closely about her and automatically made the necessary neural links.

“Link me in, Chesty,” she thought, and felt the connections open in her mind. The Night Owl’s AI was technically a Chesty2, a smaller, much more compact version of the software running on the station proper. She felt a slight thump as the Owl slid down on magnetic rails through a deck hatch and into its launch lock.

“You are linked and ready for boost, Lieutenant,” Chesty told her. “Lock evacuated. Station clearance for exit granted.”

She ran through a final check on her instrument feeds, and let the hull embracing her fade away into invisibility. This was always the scary part, the feeling that she was being dumped naked into hard vacuum. No amount of training, no thousands of hours of flight time could ever entirely override that deep-seated, thoroughly human terror of the ultimate night outside.

All systems cleared green. “Let’s do it, then.”

The drop hatch yawned and the sleek, tiny fragment of night fell into darkness.

In her mind, Lee was flying through space unencumbered by such incidentals as a ship or vacsuit. Above and behind her—though such notions as up and down were suddenly meaningless as she fell clear of the LP’s grav field—the listening post hung against the stars, a small asteroid, dust-shrouded and almost lost in the wan light from the distant, red pinpoint of the local sun. Ahead, the Stargate appeared as a vast, red-gold hoop, canted at a sharp angle to the listening post, which stayed well clear of the entrance. In the 112 years that Puller 659 had been in operation, nothing had ever emerged from that gateway other than returning Marine probes.

But there was always that inevitable first time. …

Under Chesty’s guidance, the Owl’s N’mah reactionless drive switched on, propelling it toward the Gate, which filled Lee’s view forward now, an immense, flattened band that, from this distance, appeared perfectly smooth and seamless. As moments passed, however, that illusion faded, as lines and geometric shapes became visible by the shadows cast by the distant, bloody sun.

At ninety gravities, the Owl shot forward, and the Gate swiftly grew larger, larger, then larger still. Shielded from the brutal acceleration inside the tiny craft, Lee told Chesty to maneuver closer to the ring wall as the FR-100 crossed into the tidal field, then turned sharply, falling into the ring’s turbulent lumen.

At the last possible moment, Chesty cut the drive, and the Owl dropped through the Gate, the red-gold-gray wall flashing past Lee’s awareness, the sudden gut-twisting wrench of gravitational tides clutching at her. …

And then she was through, an explosion of light bathing her wide-open mental windows. Starwall …

An apt enough name. Ringstar, Puller 659, was located in a relatively sparsely populated area of space, out in the Orion Spur of the Cygnus Galactic Arm, just a few hundred light-years from Sol. The Starwall system, however, was an estimated eighteen thousand light-years closer in toward the Galaxy’s central hub. From here, inside the dense banks of interstellar dust and gas that enclosed the Hub and shrouded its glow from the suburbs of the spiral arms, the galactic core literally appeared to be a near-solid wall of stars, presenting a vista like the heart of a globular cluster, but on an impossibly vaster scale, a teeming beehive of billions of closely packed suns, their clotted masses wreathed through with twisted and tattered ribbons of both dark and incandescent nebulae. That mass of stars had an overall reddish tinge to it; most of the stars of the Hub were ancient Population II suns, poor in metals, cooler than the predominantly hot, metal-rich and spendthrift blue stars of the spiral arms.

Lee’s warning systems began their steady and expected drumbeat. Radiation levels on this side of the Gate were high—high enough to fry an unprotected human in seconds, high enough to overwhelm even the Night Owl’s protective shielding within an hour or two at most. For safety’s sake, the clock was running; Lee had a stay-time of forty minutes on this side of the Gate, a quite literal deadline by which she had to return to the listening post, or die.

She scarcely noticed those warnings, however, for her attention had been grabbed by a danger far more immediate. Movement and proximity snatched at her awareness, and she looked up, relative to her own alignment. …

It was a Xul huntership. Of that, there could be no doubt. It appeared small, thanks to its distance, but her sensor inputs were giving her a mental download giving the thing’s range, size, mass … gods, it was huge.

The Xul warhsips encountered by Humankind so far had come in a variety of sizes and configurations, but all were enormous, well over a kilometer in length, and more often two. The Xul, for whatever reason, liked to build big.

This model had been named the Type III by Marine Intelligence, and was designated as the Nightmare class. Unlike the slender needles of Types I and II, the Nightmare was an immense flattened and elongated spheroid two kilometers across, its surface pocked and marked by countless structures and surface irregularities laid out in geometric arrays of almost fractal complexity. The Singer, discovered eight centuries before beneath the ice of Europa’s world-ocean, had been of this type. The monster was larger than the asteroid shrouding the Puller listening post … but was entirely artificial, apparently grown through the Xul equivalent of nanotechnology.

Just why they built their ships and bases on such a large scale remained one of the deeper mysteries of Xul technology. Encounters with the Xul over the past eight centuries had demonstrated that they almost certainly did not possess an organic component; as near as the various human intelligence services could determine, the Xul was a gestalt of myriad machine intelligences, some of them artificial like AIs, but some possibly originally recorded and uploaded into machine bodies from the organic originals millions of years ago.

These UIs, as they were now known, Uploaded Intelligences, were virtually immortal. Imbedded within the tightly meshed and folded circuitry that filled most of the huge Xul ships, they couldn’t be said to be truly alive, not in the human sense, and they certainly didn’t require the life-support systems found on any human-manned spacecraft.

Lee watched the complicated surface of the Xul monster glide slowly past—nearly ten kilometers away, near the center of the Gate opening, but large enough even at that range to occult the massed stars beyond like an ink-black shadow, sharp enough and detailed enough that she felt like she could reach up and touch it. It took her a moment to realize that she was on a parallel course; like her, it had only recently emerged from the Stargate behind her and was also moving into the Starwall system, but at a slightly slower speed so that she was catching up with and slowly passing it. From her perspective, it seemed to her that the Xul vessel was standing still, or even moving past her in the other direction, toward the Gate.

The Nightmare’s presence suggested answers to several questions. This side of the Gate must have been retuned by the Xul to another Gate, one other than the one at Puller 659. As a result, the four missing probes had been lost either because they’d passed through the returned Gate to that other system … or just possibly because they’d been in the process of returning and been brushed aside by this giant just as it emerged into the Starwall system.

To a monster like the Xul Nightmare, those probes must have been insignificant, dismissed as drifting fragments of meteoric debris. On that scale, Lee’s FR-100 was little larger; so long as she didn’t change her vector, she should be ignored.

Should be. So much about the Xul—both the limits of their technology and the leadings of their psychology—still were utter unknowns.

But it’s so far, so good, she thought, watching the monster slide past in the distance. She was glad she’d told Chesty to steer her closer to the ringwall, though. Had she emerged from the Gate near the center of its opening, she might well have slammed headlong into the ass end of that thing.

That didn’t let her out of the woods, though. If she applied power to decelerate in order to reverse course and return to the Gate, the Xul monster might easily pick up her energy signature; scraps of interstellar debris did not reverse course on their own, nor did they radiate the clouds of neutrinos that were the waste product of tapping the virtual energy of the Quantum Sea.

Lee felt a small shiver at the base of her neck, a prickling warning of danger. If she couldn’t reverse course, she would die of radiation poisoning in short order. And, even if she did reverse course … the Xul Nightmare’s presence suggested that the Stargate on this side was now attuned to a different star system. If she went through, she would not emerge at Puller 659, but in some other unguessable but absolutely guaranteed remote location. Chesty could retune the Gate for a return, of course; the Puller 659 Gate’s coordinates were programmed into him.

But that would be a rather nasty give-away to the Xul here at Starwall, who would certainly be monitoring the Gate’s settings. Regulation One-alpha, drilled into every Marine standing duty at a Gate listening post, was to lay low and keep a low profile, to not attract Xul attention to human activities. Humankind had survived for the past eight centuries only because they’d managed, on the whole, to stay off the metaphorical Xul radar.

“Chesty?” she asked. “Are you picking anything up from over there? Can you piggyback it?”

“We are intercepting the usual RF leakage,” the AI replied. “I am attempting to locate a viable frequency with which to establish a tap.”

Xul ships leaked, at least at radio frequencies. The millions of kilometers of nanoelectronic circuitry and processors packed into each of those immense hulls gave off a constant hiss and murmur of radio noise as a kind of metabolic by-product, and the Xul never seemed to bother with shielding. Some theorists suggested that the radio noise served an almost organic function, helping to reassure individual Xul ship-entities that others of their kind were near.

Ever since the first studies carried out on the Singer eight centuries before, humans had looked for ways to turn this fact to their advantage. It was possible, for instance, to use some Xul frequencies as carrier waves, allowing human-developed AI programs to upload into a Xul computer network and have a look around. The technique was called piggybacking, and Marine listening posts often used it in attempts to gather yet more intelligence on the poorly understood and still mysterious Xul.

There was an ancient aphorism, something all Marines learned in boot camp, something from the writings of Sun Tzu in The Art of War It stated that if the warrior knew himself, but not the enemy, he would be victorious only half the time. If he knew the enemy, but not himself, he would, again, be victorious only one battle out of two. Only if the warrior knew the enemy and himself could he hope to win every battle. …

The Marine philosophy, begun in the crucible of recruit training, was designed to create a sure knowledge of self. Unfortunately, even after eight centuries, the Xul were still largely an utterly alien quantity. Xenocultural theorists were still divided as to whether the Xul could properly be called living beings … or even whether they were self-aware, both sentient and conscious in the same way that humans understood the terms. In most ways, they appeared to be machine intelligences, like human-designed AIs, but on a far vaster and more powerful scale.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.