Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «September 1, 1939»

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Ian Sansom 2019

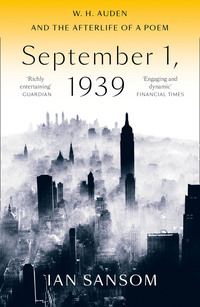

Cover design by Heike Schüssler

Cover photograph © Getty Images/Hulton Archive/Stringer

Ian Sansom asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Unpublished writings by W. H. Auden are quoted with the permission of the Estate of W. H. Auden.

‘September 1, 1939’ from Another Time by W. H. Auden (1940, Faber & Faber).

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007557233

Ebook Edition © July 2019 ISBN: 9780007557226

Version: 2020-06-17

Dedication

For N. J. Humphrey

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 Wow!

7 September 1, 1939

8 Your Least Favourite Auden Poem?

9 Just a Title

10 1

11 I ≠ A

12 The Modern Poet

13 Not Standing

14 A Not Insignificant Americanism

15 A Rolling Tomato Gathers No Mayonnaise

16 Clever-Clever

17 Various Cosmic Thingummys

18 Offensive Smells

19 2

20 A Little Spank-Spank

21 Strangeways

22 Is Berlin Very Wicked?

23 Do Not Tell Other Writers to F*** Off

24 3

25 The Latin for the Judgin’

26 4

27 Aerodynamics

28 Get Rid of the (Expletive) Braille

29 Tower of Babel Time

30 5

31 The Liquid Menu

32 Below Average

33 Soft Furnishings

34 6

35 Talking Trash

36 You Can’t Say ‘Mad’ Nijinsky

37 7

38 Homo Faber

39 8

40 As Our Great Poet Auden Said

41 We Must Die Anyway

42 9

43 Twinkling

44 A New Chapter in My Life

45 Twenty-Five Years’ Worth of Reading

46 Also by Ian Sansom

47 About the Author

48 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivv1234567910111213151617181920212223242526272829303132333435363738394041424344454748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149151153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167169171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191193195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237239241242243244245246247248249250251252253255257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341ii

Wow!

At just after five o’clock on 11 June 1956, W. H. Auden stood up to give his inaugural lecture as Oxford Professor of Poetry at the Sheldonian Theatre, the very heart of the university, adjacent to the Bodleian and the Clarendon Building, opposite Blackwell’s bookshop on Broad Street, and a short walk from Auden’s old college, Christ Church.

It was a warm afternoon. Auden, famously crumpled, had enjoyed, I imagine, a good lunch and was sweating in his thick black MA gown with its distinctive, gaudy crimson shot-silk hood. He was buzzing: he had long since adopted a strict chemical daily routine to enable him to work more efficiently. These ‘labor-saving devices’, in what he called his ‘mental kitchen’, included not only strategic quantities of alcohol, coffee and tobacco, but also the amphetamine Benzedrine, as a pick-me-up at breakfast, and the barbiturate Seconal, to bring him down at night. ‘If you ever get that depressed unable-to-concentrate feeling, try taking Benzidrine [sic] Tablets,’ he advised his friend Annie Dodds, ‘but not too many.’

The Sheldonian was full: the audience were expectant. The University Chancellor, the Vice-Chancellor and the Proctors were in full fig – black gowns, gold lace, white tie. The undergraduates and graduate students wore subfusc and were crammed into the high-tiered seating under the lurid sunburst-orange ceiling fresco by King Charles II’s court painter Robert Streater, which depicts Truth descending upon the Arts and Sciences like the wolf on the fold, dispelling ignorance from the university.

It was quite a return.

In 1928 Auden had left Oxford with a miserable Third in English, and his appointment as professor was not without controversy. The university elects its Professor of Poetry unusually – indeed, uniquely – by a vote among its graduates, and Auden remained a divisive figure in England. The two other candidates were Harold Nicolson, a well-connected author, diplomat, politician and husband to Vita Sackville-West, and G. Wilson Knight, an eminent and massively prolific Shakespeare scholar, author of both the standard work on Shakespearean tragedy, The Wheel of Fire (1930), and the bestselling The Sceptred Isle: Shakespeare’s Message for England at War (1940).

Nicolson and Wilson Knight had obvious merits – they were sensible, distinguished, learned individuals. And they were easily and identifiably English. Auden, in contrast, was an eccentric, remote, supernational sort of a figure, a poet celebrity, English-born but now a self-proclaimed New Yorker who had developed a strange, drawling mid-Atlantic accent – recently further complicated after he’d had his few final teeth removed and been fitted with dentures – and who made a living ‘on the circuit’, touring American campuses delivering his lectures and reading his poems. He saw himself as a kind of itinerant preacher:

An air-borne instrument I sit,

Predestined nightly to fulfil

Columbia-Giesen-Management’s

Unfathomable will,

By whose election justified,

I bring my gospel of the Muse

To fundamentalists, to nuns,

to Gentiles and to Jews.

(Auden, ‘On the Circuit’)

Auden’s usual touring schedule did not include the English Midlands. The closest he came was spending his summers in bohemian fashion on the Italian island of Ischia with his lover Chester Kallman. (‘They engaged a handsome local boy known as Giocondo’, notes one biographer, ‘to look after the house, and possibly also to provide sexual services.’) Though popular among undergraduates, who weren’t entitled to vote, Auden was not considered a serious candidate for the professorship by the more senior members of the university.

There was also the small matter of his having abandoned England in 1939, and having taken the oath of allegiance and become an American citizen in 1946, something he was never allowed to forget, and for which he was certainly never forgiven. On learning of Auden’s death in 1973, the novelist Anthony Powell was rendered almost speechless with joy and disgust, declaring, ‘I’m delighted that shit has gone … It should have happened years ago … Scuttling off to America in 1939 with his boyfriend like a … like a …’ In 1956, memories of the war were still fresh. G. Wilson Knight had served as a dispatch rider in World War I, and in World War II Nicolson had been parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Information. Auden’s war record was rather less distinguished. When he had left England in 1939, questions were asked in Parliament about his departure: he was a disappointment to the nation. When he arrived back in London at the end of the war, wearing his honorary US Army major’s uniform, as part of his role in the US Strategic Bombing Survey, people were appalled.

But if England wasn’t too sure about Auden, Auden wasn’t at all sure he wanted to spend too much time in England delivering the one lecture per term required by the university statutes. ‘The winter months’, he wrote to Enid Starkie, the flamboyant, publicity-seeking, cigar-smoking Rimbaud scholar who had proposed him as a candidate, ‘are those in which I earn enough dollars to allow me […] to devote myself to the unprofitable occupation of writing poetry. I do not see any way in which I could earn the equivalent if I had to reside in England during that period.’ Nonetheless, he allowed his nomination to go forward.

On Thursday, 9 February 1956, the result was announced.

Wilson Knight had attracted just 91 votes. Nicolson had secured 192. And Auden topped the poll with 216. He was therefore elected as professor, succeeding his old friend Cecil Day Lewis.

‘You have chosen for your new Professor’, Auden began his inaugural lecture – typically teasing and self-effacing – ‘someone who has no more right to the learned garb he is wearing than he would have to a clerical collar.’ Setting out the terms of his professorship, he went on:

Speaking for myself, the questions which interest me most when reading a poem are two. The first is technical: ‘Here is a verbal contraption. How does it work?’ The second is, in the broadest sense, moral: ‘What kind of a guy inhabits this poem? What is his notion of the good life or the good place? His notion of the Evil One? What does he conceal from the reader? What does he conceal even from himself?’

This book does a very simple thing. It asks Auden’s two obvious questions of his own poem ‘September 1, 1939’. How does it work? And what kind of a guy inhabits this poem?

In a sense, the first question is easy to answer. ‘September 1, 1939’ consists of 99 lines, written in trimeters, divided into nine eleven-line stanzas with a shifting rhyme scheme, each stanza being composed of just one sentence, so that – as the poet Joseph Brodsky has usefully pointed out – the thought unit corresponds exactly to the stanzaic unit, which corresponds also to the syntactic and grammatical unit. Which is neat.

Too neat.

Because, of course, this is only the beginning of an understanding of how the poem works. It takes us only to the very edge of the poem, to the outskirts of its territory. In order properly to understand ‘September 1, 1939’, we would have to investigate why Auden chose this rigorous, cramped, bastard form – and not, for example, an elegant villanelle, or a sestina, or a double sestina, traditional and virtuoso forms at which he excelled. And why did he begin a poem with an ‘I’, undoubtedly the most depressing and dreary little pronoun in the English language? And who is this ‘I’? And why do they ‘sit’ in one of the dives – why aren’t they standing? And how are they sitting? At a table? And where is this dive? And why is it a ‘dive’? And what exactly were the ‘clever hopes’ of this ‘low dishonest decade’? And why so many double adjectives? And so on and so on. This book will attempt to follow the route of some of these obvious but necessary questions, mapping the poem word by word, line by line and phrase by phrase.

And as for the ‘guy’ who inhabits this poem? What is his notion of the good life or the good place? What is his notion of the Evil One? What does he conceal from the reader? What does he conceal from himself?

These are also good questions.

‘September 1, 1939’ is an important poem, I believe, and worthy of scrutiny, because it provides us with a rare glimpse of a writer in the act of reinventing himself, at a culminating moment in world affairs. Like Ulysses and The Waste Land, like Guernica and The Rite of Spring, this poem is a snapshot of the artist in extremis, working at the farthest reaches of his capacities.

But ‘September 1, 1939’ is not only one of those rare coincidences in literature in which the force of history meets personal psychology and ideology, to produce something truly marvellous – it also represents a moment of crisis, where the great pressures at work both outside and inside the poem force certain flaws to become apparent. Not only that, it’s a poem whose troubled history involves its own self-destruction and reinvention: it therefore represents the art object as living organism, something that grows and changes, that is understood, misunderstood, appropriated, abandoned, recycled and reused, again and again. Above all, it is a poem that still reverberates with meaning and controversy, a poem that readers return to at times of personal and national crisis: it turns out that the ‘guy’ who inhabits Auden’s poem is us.

The aim of this book, then, is to demonstrate how a poem gets produced, consumed and incorporated into people’s lives – how, in the words of another of Auden’s great poems, ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’, the work of a poet becomes ‘modified in the guts of the living’, and not just modified, but colonised, metabolised, metastasised. It is a record of how and why we respond to great art.

Or, at least, it is a record of how and why I have responded to this particular example of great art, and of how the work of this particular poet has become modified in these particular guts – modified, metabolised and metastasised. There has been so much written about Auden by so many people – brilliant and insightful people – over so many years, that the best I can do is to try and explain the impact that reading and studying this poem has had on me. Not because there’s anything particularly interesting about me – on the contrary – but because I might usefully represent the common reader, the sensual man-in-the-street, the entirely average individual with a rather unusual interest in a particular work of art.

In the end, I hope that this book amounts to more than a record of my own peculiar tastes and notions and gives expression to that common sense of awe and inadequacy that we might all experience in the presence of great art, for how can one possibly begin to cope with someone like Auden, who was clearly a genius, and with something like this, which is clearly a masterpiece? What can one possibly say, except … ‘Wow!’?

September 1, 1939

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-Second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism’s face

And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow,

‘I will be true to the wife,

I’ll concentrate more on my work’,

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the deaf,

Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

Your Least Favourite Auden Poem?

INTERVIEWER: What’s your least favourite Auden poem?

AUDEN: ‘September 1, 1939.’

Michael Newman, interview with W. H. Auden, The Paris Review (1972)

Me too.

*

I have been trying to write a book about W. H. Auden for twenty-five years.

It could not be described as a cost-effective enterprise.

It may not have been the best use of my time.

The poet cannot understand the function of money in modern society because for him there is no relation between subjective value and market value; he may be paid ten pounds for a poem which he believes is very good and took him months to write, and a hundred pounds for a piece of journalism which costs him but a day’s work.

(Auden, ‘The Poet & The City’)

A lot can happen to someone in twenty-five years – though it hasn’t really happened to me. I have overcome no addictions. I have suffered no serious mental or physical breakdowns. There were no major achievements, no terrible lows: I am, in all regards, average to the point of being dull. There is, alas, no backstory to this story. This is not one of those books.

It is not a book about grief.

It is not a book about loss.

It is not a book about some great self-realisation.

I did not go – I have not been – on any kind of a journey with W. H. Auden.

I do not believe that Auden provides readers with the key to understanding life, the universe and everything. Reading Auden has not made me happier, healthier, or a better or more interesting person.

Perhaps the only strange or remarkable thing to have happened to me over the past twenty-five years is that I have been trying to write a book about W. H. Auden.

The only possible conclusion, I suppose, after all this time, is either that I haven’t been trying hard enough, or that I’m simply not up to the job.

Or, possibly, both.

*

Completed finally in my early fifties, in vain and solitary celebration, this – whatever this is – turns out to be proof against itself.

For decades I had imagined writing a big book about Auden’s life and work, a truly great book, a magnum opus.

I have managed instead to write a short book about just one of his poems. At the very moment of its completion, the work turns out to be evidence of failure. Opus minus.

In the end, one feels only depletion, disgust and disappointment, the sense that one has once again turned manna into gall, the everlasting taste of bitterness.

*

(I am reading the collected poems of Bertolt Brecht, in translation. I come across this, ‘Motto’:

This, then, is all. It’s not enough, I know.

At least I’m still alive, as you may see.

I’m like the man who took a brick to show

How beautiful his house used once to be.

This book is my brick: it is proof of how beautiful the house might have been.)

*

Auden wrote all of his prose, he claimed, because he needed the money.

I have written all of my prose because I am not a poet.

And I needed the money.

Underneath the abject willow,

Lover, sulk no more;

Act from thought should quickly follow:

What is thinking for?

Your unique and moping station

Proves you cold;

Stand up and fold

Your map of desolation.

(Auden, ‘Underneath the abject willow’)

Twenty-five years, though – can you imagine? – twenty-five years of failing to write a book.

*

It’s perhaps not entirely uncommon.

There are, of course, individuals who write great books at great speed, and with great success, and to great acclaim – Auden’s first book with Faber was published when he was just twenty-three and he went on to produce a book about every three years for the rest of his life. The truth is, it takes most of us years to get a book published, and even then those books end in massive failure: neglected, overlooked and forgotten.

(My own books, it should probably be admitted, have all ended in massive failure: neglected, overlooked and forgotten. It’s nature’s way. There’s a critic, Franco Moretti, notorious in literary studies, who has pioneered the study of literature as a kind of data set, and he has an essay, ‘The Slaughterhouse of Literature’, which is all about clues in detective literature, and which is an excellent essay, though I’m less interested in his thoughts about clues in detective literature than I am in his redolent title phrase – which he stole from Hegel, actually – because it acknowledges what is rarely acknowledged, which is the hard, painful truth that to study literature, never mind to participate in it, is to become a witness to the sheer horrors of literary history, as savage and violent as all history. ‘The majority of books disappear forever –’ writes Moretti, ‘and “majority” actually misses the point: if we set today’s canon of nineteenth-century British novels at two hundred titles (which is a very high figure), they would still be only about 0.5 percent of all published novels. And the other 99.5 percent?’ I am one of the 99.5 per cent: I am one of the living dead, the Great Unread. This book too will undoubtedly end up in the slaughterhouse, as it should and as it must.)

*

This book I began long before I had written or even contemplated writing any of my other books. It was the first – and it may be the last. It may be time to admit defeat, to admit to my own obvious lack of whatever it was that Auden had, which was just about everything. In Auden, one might say – if it didn’t sound so dramatic, if it didn’t sound like I was trying to talk things up by talking myself down – in Auden was my beginning and in Auden is my end.

*

One might, I suppose, console oneself with the knowledge that even some of Auden’s books were not entirely successful: Academic Graffiti, City Without Walls.

But to dwell on the minor faults and failings of the great is hardly a comfort.

It is merely another sign of one’s own inadequacies.

The greater the equality of opportunity in a society becomes, the more obvious becomes the inequality of the talent and character among individuals, and the more bitter and personal it must be to fail, particularly for those who have some talent but not enough to win them second or third place.

(Auden, ‘West’s Disease’)

But surely – surely? – literature is not a competition. Literature is not a sport. One cannot measure oneself by the usual standards of success.

The writer who allows himself to become infected by the competitive spirit proper to the production of material goods so that, instead of trying to write his book, he tries to write one which is better than somebody else’s book is in danger of trying to write the absolute masterpiece which will eliminate all competition once and for all and, since this task is totally unreal, his creative powers cannot relate to it, and the result is sterility.

(Auden, ‘Red Ribbon on a White Horse’)

Let’s not kid ourselves.

It is a competition.

It is a sport.

One does measure oneself by the usual standards of success.

When writing about any great writer – or indeed about anyone who has achieved great things – one can’t help but compare oneself.

*

(Throughout his life, Philip Larkin often measured himself against Auden. Auden, for him, was the Truly Great Man: Philip Larkin loved Auden. When he bought a car in 1984, for example, an Audi, he said he liked the name ‘because it reminds me of Auden’. In a letter to a friend in 1959, extolling the virtues of Auden’s poem ‘Night Mail’, he wrote in horrible realisation, ‘HE’D BE ABOUT SEVEN YEARS YOUNGER THAN ME,’ but then quickly added, ‘I reckon he’d shot his bolt by the age of 33, actually.’ Again, when Larkin was awarded the Queen’s Medal for Poetry in 1965, he told an interviewer, ‘Take this Queen’s Medal. I’m 42, but he got it for “Look, Stranger!” when he was 30. Mind you, I feel he was played out as a poet after 1940.’ This scuttering between despair and disdain is typical of Larkin in general but it is also typical of his attitude towards Auden in particular. He prefaced a home-made booklet of poems in 1941 with the gulping confession ‘I think that almost any single line by Auden would be worth more than the whole lot put together.’ When, in 1972, Auden’s bibliographer Barry Bloomfield asked Larkin if he might be his next subject, Larkin expressed both delight and dismay: Bloomfield ‘has switched to me now Auden’s gone’, he told his friend Anthony Thwaite; ‘I am not much more than a five-finger exercise after Auden,’ he apologised to Bloomfield.)

*

If Philip Larkin was no more than a five-finger exercise compared to Auden, then this – this! – is, what? At the very best, a one-note tribute?

*

Polyphony

↓

Monophony

↓

Penny whistle and kazoo

*

Parnassus after all is not a mountain,

Reserved for A.1. climbers such as you;

It’s got a park, it’s got a public fountain.

The most I ask is leave to share a pew

With Bradford or with Cottam, that will do.

(Auden, ‘Letter to Lord Byron’)

*

Park?

Fountain?

Pissoir.

*

Perhaps one of the only things the rest of us share with the truly great writers is the sense of struggle, the sense of inadequacy.

Flaubert: ‘Sometimes when I find myself empty, when the expression refuses to come, when, after having scrawled long pages, I discover that I have not written one sentence, I fall on my couch and remain stupefied in an internal swamp of ennuis.’

Gerard Manley Hopkins: ‘Birds build – but not I build; no, but strain, / Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.’

Katherine Mansfield: ‘For the last two weeks I have written scarcely anything. I have been idle; I have failed.’

We all know that feeling, that sense of despair and woe-is-me and all-I-taste-is-ashes, and all-I-touch-has-turned-to-dust.

Great writers, it seems, are not necessarily those who are most confident about their own capacities or skills. They are more often keenly aware that words are failing them, and that they are failing words. Like us, they find it difficult.

*

Or rather, most of them find it difficult: Auden was convinced of his own skills and capacities from an early age and went on to fulfil and exceed his early promise.

(His tutor at Oxford, Nevill Coghill, recalled Auden announcing his intention to become a poet. Jolly good, said Coghill – or something donnish to that effect – that should help with understanding the old technical side of Eng. Lit., eh, old chap? ‘Oh no, you don’t understand,’ replied Auden – or again, words to that effect – ‘I mean a great poet.’)

He seems never to have been lacking in confidence. He seems always to have been convinced not merely of his brilliance but of his sovereignty.

‘Evidently they are waiting for Someone,’ he told his friend Stephen Spender.

He was that Someone.

*

And me, who am I?

If nothing else, one of the things I have realised over the course of the past twenty-five years, in trying to write a book about W. H. Auden, is the obvious fact that I AM NOT W. H. AUDEN.

*

Other people realise they’re not their heroes much earlier, but I was in the slow learners’ class in school and seem to be a slow learner still.

I think I probably believed that one day – through sheer willpower and determined slog, through dogged persistence and self-discipline – I might somehow overcome my weaknesses and become an artist of some significance.

It is only recently that I have come to accept my true role and status, which is, obviously, naturally, inevitably, as an utterly insignificant bit-part player in the world of literary affairs.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.