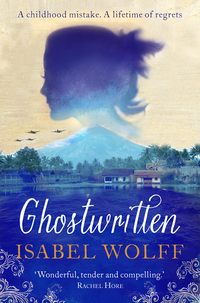

Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Ghostwritten», sayfa 2

I looked at Rick, so handsome, with his open face, short dark hair and blue gaze. I tried, and failed, to imagine life without him. We’d agreed to talk things over again the next day. Before I could think about that, though, a gong summoned us into the marquee, which was bedecked with white agapanthus and pink nerines, the tables gleaming with silver and china. We found our names, standing behind our chairs while the vicar said Grace.

Rick and I had been placed with Honor, and with Amy and Sean, whom I’d known at college but hadn’t seen for years, and an old schoolfriend of Jon’s, Al. I was glad that Nina had put him next to Honor; she’d been single for a while now, and he was very attractive. Also on our table was Nina’s godfather, Vincent Tregear. I vaguely remembered him from her twenty-first birthday. A near neighbour named Carolyn Browne introduced herself. I steeled myself for the effort of making small talk with people I don’t know; unlike Honor, I’m not good at it, and in my present frame of mind it would be harder than usual.

I heard Carolyn explain to Rick that she was a solicitor, recently retired. ‘I’m so busy though,’ she confessed, laughing. ‘I’m a governor of a local school, I play golf and bridge; I travel. I was dreading retirement, but it’s really fine.’ She smiled at Rick. ‘Not that you’re anywhere near that stage. So, what do you do?’

He unfurled his napkin. ‘I’m a teacher – at a primary school in Islington.’

‘He’s the deputy head,’ I volunteered, proudly.

Carolyn smiled at me. ‘And what about you, erm …?’

‘Jenni.’ I turned my place card towards her.

‘Jenni,’ she echoed. ‘And you’re …’ She nodded at Rick.

‘Yes, I’m Rick’s …’ The word ‘girlfriend’ made us seem like teenagers; ‘partner’ made us sound as though we were in business, not in love. ‘Other half,’ I concluded, though I disliked this too: it seemed to suggest, ominously, that we’d been sliced apart.

‘And what do you do?’ Carolyn asked me.

My heart sank – I hate talking about myself. ‘I’m a writer.’

‘A writer?’ Her face had lit up. ‘Do you write novels?’

‘No,’ I replied. ‘It’s all non-fiction. But you won’t have heard of me.’

‘I read a lot, so maybe I will. What’s your name? Jenni …’ Carolyn peered at my place card. ‘Clark.’ She narrowed her eyes. ‘Jenni Clark …’

‘I don’t write under that name.’

‘So is it Jennifer Clark?’

‘No – what I mean is, I don’t write under any name.’ I was about to explain why, when Honor said, ‘Jenni’s a ghost.’

‘A ghost?’ Carolyn looked puzzled.

‘She ghosts things.’ Honor unfurled her napkin. ‘Strange to think that it can be a verb, isn’t it? I ghost, you ghost, he ghosts,’ she added gaily.

I rolled my eyes at Honor, then turned to Carolyn. ‘I’m a ghostwriter.’

‘Oh, I see. So you write books for people who can’t write.’

‘Or they can,’ I said, ‘but don’t have the time, or lack the confidence, or they don’t know how to shape the material.’

‘So it’s actors and pop stars, I suppose? Footballers? TV presenters?’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t do the celebrity stuff – I used to, but not any more.’

‘Which is a shame,’ Honor interjected, ‘as you’d make far more money.’

‘True.’ I rested my fork. ‘But I didn’t enjoy it.’

‘Why not?’ asked Al, who was on my left.

‘It was too frustrating,’ I answered, ‘having to battle with my subjects’ egos, or finding that they didn’t turn up for the interviews; or that they’d give me some brilliant material then the next day tell me that I wasn’t to use it. So these days I only do the projects that interest me.’

Honor, who has a butterfly mind, was now discussing ghosts of the other kind. ‘I’m sure they exist,’ she said to Vincent Tregear. ‘Twenty years ago I was staying with my cousins in France; it was a warm, still day, just like today, and we were exploring this abandoned house. It was a ruin, so we could see right up to the roof … And we both heard footsteps, right above us, on the non-existent floorboards.’ She gave an extravagant shudder. ‘I’ve never forgotten it.’

‘I believe in ghosts,’ Carolyn remarked. ‘I live on my own, in an old house, and at times I’ve been aware of this … presence.’

Amy nodded enthusiastically. ‘I’ve sometimes felt a sudden chill.’ She turned to Sean. ‘Do you remember, darling, last summer? When we were in Wales?’

‘I do,’ he answered. ‘Though I believe it was because you were pregnant.’

‘No: pregnancy made me feel hot, not cold.’

‘A few years ago,’ said Al, ‘I was asleep in my flat, alone, when I suddenly woke up, convinced that someone was sitting on my bed.’

I shivered at the idea. ‘And you weren’t dreaming?’

He shook his head. ‘I was wide awake. I can still remember the weight of it, pressing down on the mattress. Yet there was no one there.’

‘How terrifying,’ I murmured.

‘It was.’ He poured me some water then filled his own glass. ‘Has anything like that ever happened to you?’

‘It hasn’t, I’m glad to say. But I don’t dismiss other people’s experiences.’

‘I’ve always been sceptical about these things,’ Sean observed. ‘I believe that if people are sufficiently on edge they can see things that aren’t really there. Like Macbeth seeing the ghost of Banquo.’

‘Shake not thy gory locks at me!’ intoned Honor, then giggled. ‘And Macbeth certainly is on edge by then, isn’t he, having murdered – what – four people?’ Then she went off on some new conversational tangent about why it was considered unlucky for actors to say ‘Macbeth’ inside a theatre. ‘People think it’s because of the evil in the story,’ she prattled away as a waiter took her plate. ‘But it’s actually because if a play wasn’t selling well, the actors would have to quickly rehearse Macbeth as that’s always popular, so doing Macbeth became associated with ill luck. Now … what are we having next?’ She picked up a gold-tasselled menu. ‘Sea bass – yum. Did you know that sea bass are hermaphrodites? The males become females at six months.’

Al, clearly uninterested in the gender-switching tendencies of our main course, turned to me. ‘So what sort of books do you write?’

‘A real mix,’ I answered. ‘Psychology, health and popular culture; I’ve done a diet book, and a couple of gardening books …’

I thought of my titles, more than twenty of them, lined up on the shelf in my study.

‘So you must learn a huge amount about all these things,’ Al said.

‘I do. It’s one of the perks.’

Carolyn sipped her wine. ‘But do you get any kind of credit?’

‘No.’

‘I thought that with ghostwritten books it usually said “with” so-and-so or “as told to”.’

‘It depends,’ I said. ‘Some ghostwriters ask for that. I don’t.’

‘So your name appears nowhere?’

‘That’s right.’

She frowned. ‘Don’t you mind?’

I shrugged. ‘Anonymity’s part of the deal. And of course the clients like it that way. They’d prefer everyone to think they’d written the book all by themselves.’

Carolyn laughed. ‘I couldn’t bear not to have any of the glory. If I’d worked that hard on something, I’d want people to know!’

‘Me too,’ chimed in Honor. ‘I don’t know why you want to hide your light under a bushel quite so much, Jen.’

‘Because it’s enough that I’ve enjoyed the work and been paid for it. I’m happy to be … invisible.’

‘You were always like that,’ Honor went on. ‘You were never one to seek the limelight – unlike me,’ she giggled. ‘I enjoy it.’

‘So are you still acting?’ Sean asked her.

‘Not for five years now,’ she answered. ‘I couldn’t take the insecurity any more, so I went into radio, which I love.’

‘I’ve heard your show,’ Amy interjected. ‘It’s really good.’

‘Thanks.’ Honor basked in the compliment for a moment. ‘And you two have had a baby, haven’t you?’

‘We have,’ Amy answered. ‘So I’m on maternity leave …’

‘And what are you working on now, Jenni?’ Carolyn asked.

I fiddled with my wine glass. ‘A baby-care guide.’

‘How lovely,’ she responded. ‘And are you a mum?’

My heart contracted. ‘No.’ I sipped my wine.

‘Doesn’t that make it difficult? Writing a book about something you haven’t been through yourself?’

‘Not at all. The client’s talked extensively to me about her experience – she’s a midwife – and I’ve written it up in a clear and, I hope, engaging way.’

‘I must buy it,’ Amy said to me. ‘What’s it called?’

‘Bringing Up Baby. It’ll be out in the spring. But I always get given a few complimentary copies, so if you give me your address I’ll send you one.’

‘Oh, that’s kind. I’ll write it down …’ Amy began looking in her bag for a pen.

‘You can contact me through my website,’ I suggested. ‘Jenni Clark Ghostwriting. So … how old’s your baby?’

At that Sean took out his phone and swiped the screen. ‘She’s called Rosie.’

I smiled at the photo. ‘She’s gorgeous. Isn’t she lovely, Honor?’

Honor peered at the image. ‘She’s a little beauty.’

‘She’s what, six months?’ I asked.

Amy’s face glowed with pride. ‘Yes – she’ll be seven months a week on Wednesday.’

‘So is she crawling?’ I went on, ‘Or starting to roll over?’ Beside me I could feel Rick stiffen.

‘She’s crawling beautifully,’ Amy replied. ‘But she’s not rolling over yet.’

Sean laughed. ‘It’ll be nerve-wracking when she does.’

‘You won’t be able to leave her on the bed or the changing table,’ I said. ‘That’s when lots of parents put the changing mat on the floor – not that I’m a parent myself, but of course we cover this in the book …’ Rick had tuned out of the conversation and was talking to Carolyn again. Al turned to me. ‘So can you write about any subject?’

‘Well, not something I could never relate to,’ I answered, ‘like particle physics – not that I’d ever get chosen for a book like that. But I’ll do almost any professional writing job: corporate reports, press releases, business pitches, memoirs …’

‘Memoirs?’ echoed Vincent Tregear. ‘You mean, writing someone’s life story?’

‘Yes – usually an older person, just for private publication.’

‘Do you enjoy that?’ Vincent wanted to know.

‘Very much. In fact it’s the best part of the job. I love immersing myself in other people’s memories.’

Vincent looked as though he was about to say something, but then Carolyn began asking him about golf, Amy was telling Rick about yoga, and Honor was chatting to Al about his work as an orthodontist. She was drawn to him, I could tell. Good old Nina for putting them together. Suddenly Honor looked at me, grinned, then tapped her teeth. ‘Al says I have a perfect bite.’

I raised my glass. ‘Congratulations!’

‘Not just good,’ Honor said. ‘Perfect!’

‘Don’t let it go to your head,’ Al said.

She laughed. ‘Where else is my bite supposed to go?’

Soon it was time for the speeches and toasts; the cake was cut, then after coffee there was a break before the evening party was to start.

Amy and Sean had to leave, to get back to their baby. Vincent Tregear also said his goodbyes. As the caterers moved back the tables, Rick and I went out into the garden.

We sat on a bench, watching the sky turn crimson, then mauve, then an inky blue in which the first stars were starting to shine.

‘Well … it’s been a great day,’ Rick pronounced. The awkwardness had returned, squatting between us like an uninvited guest.

‘It’s been a lovely day,’ I agreed. ‘We should …’

‘What?’ he murmured.

My nerve failed. ‘We should go inside. It’s getting cold.’

Rick stood up. ‘And the band’s started.’ He held out his hand.

So we returned to the marquee where Jon and Nina were dancing their first waltz. Soon everyone took to the floor. But as Rick’s arms went round me and he pulled me close, I felt that he was hugging me goodbye.

TWO

‘So … what are we going to do?’ Rick asked me gently the following day.

We’d had lunch – not that I’d been able to eat – and now faced each other across our kitchen table. I shook my head, helplessly. I didn’t trust myself to speak.

‘We’ve got three options,’ Rick went on. ‘One, I change my mind; two, you change your mind; or three …’

I felt my stomach clench. ‘I don’t want to break up.’

‘Nor do I.’ Rick exhaled, hard, as though breathing on glass, then he looked at me, his blue eyes searching my face. ‘I do love you, Jen.’

‘Then you should be happy to let me have what I want.’

He flinched. ‘You know it’s not that simple.’

A silence fell in which we could hear the rumble of traffic from the City Road.

‘I keep thinking about this quote I once read,’ Rick said after a moment. ‘I can’t remember who it’s by, but it’s about how love doesn’t consist in gazing at the other person, but in looking together in the same direction.’ He shrugged. ‘But we’re not doing that.’

I cradled my coffee mug with its pattern of red hearts. ‘We’ve been together for a year and a half,’ I said quietly. ‘We’ve lived together for nine months, and we’ve been happy. Haven’t we?’ I glanced at the framed photo collage that I’d made of our first year together. There were snaps of us on top of Mount Snowdon, walking on the South Downs, sitting on the swing seat in his parents’ garden, cooking together, kissing. Then my eyes strayed to Nina’s wedding invitation on the kitchen dresser. I bitterly regretted having teasingly asked Rick when we might take our relationship forward.

‘We have been happy,’ Rick said at last. ‘That’s what makes it so hard.’

Another silence enveloped us. I could hear the hum of the fridge. ‘There is a fourth option,’ I said, ‘which is to go on as we were. So let’s just … forget marriage.’

Rick stared at me as though I were speaking in tongues. ‘This isn’t about marriage, Jen.’

I glanced at my manuscript, the typed pages stacked up on the table. Bringing Up Baby. From Newborn to 12 Months, the Definitive Infant-Care Guide. A page had fallen to the floor.

‘So what are we going to do?’ Rick asked me again.

‘I don’t know.’ A wave of resentment coursed through me. ‘I only know that I was always honest with you.’ As I picked up the sheet, random sentences leapt out at me. Great adventure of parenthood … bliss of holding your baby for the first time … what to expect, month by month.

‘You were honest.’ Rick nodded. ‘You told me right from the start that you didn’t want to have children and that this was something I had to know if we were to get involved.’

‘Yes,’ I said hotly, ‘and you said you didn’t mind, because you work with children every day. You said that your brother has four kids, so there was no pressure on you to have them. You told me that you’d never been bothered about it and that people can have a good life without children – which is true.’

‘I did feel like that, Jenni. But I’ve changed.’

‘Well, I wish you hadn’t, because now we’ve got a problem.’

Rick pushed back his chair; he went and stood by the French windows. Through the panes the plants in our small walled garden looked dusty and withered. I’d been too distracted and upset to water them. ‘People do change,’ he said quietly. ‘They’re allowed to change. And it’s crept up on me over the past few months. I’ve wanted to talk to you about it but was afraid to, precisely for this reason, but now you’ve brought the issue into the open.’

‘Why have you changed?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t know – probably because I’m nearly forty now.’

‘You were nearly forty when we met.’

‘Or maybe it’s seeing the kids at school develop and grow, and wishing that I could watch my own kids do that.’

‘That didn’t seem to worry you before.’

‘True. But now it does.’

I glanced at the manuscript. ‘I think it’s because I’ve been working on this baby-care book.’ I felt my throat constrict. ‘I wish I’d never agreed to do it.’

‘The book has nothing to do with it, Jen. I wanted to be with you so much that I convinced myself I didn’t want children. Then I began to believe that because we were in love we’d naturally want to have them. So I thought you’d change your mind.’

‘Which is what you’re hoping for now?’

Rick sighed. ‘I guess I am. Because then we’d still have each other, but with the chance of family life too. I’ll be applying for head teacher posts before long: I’d like to try for jobs outside London, if you were happy to move.’

‘I’d be happy to be wherever you were,’ I said truthfully.

‘Jen …’ Rick’s face was full of sudden yearning. ‘We could have a great life: we’d be able to afford a bigger place.’ He looked around him. ‘This flat’s so small.’

‘I don’t care. I’d live in a bedsit with you if I had to. But, yes, it would be wonderful to have more space – with a bigger garden.’

He nodded. ‘I’ve been thinking about that garden a lot. I see a lawn, with children running around on it, laughing. But then they fade, like ghosts, because I know you don’t want any.’ Rick sat down again, then reached for my hands. ‘I want nothing more than to share my life with you, Jen, but we have to want the same things. And the question of whether or not we have children isn’t one that we can compromise on; and if we can’t agree about it—’

I withdrew my hands. ‘Let’s imagine that I do change my mind. What if we then find that I can’t have kids?’

‘At least I’d know that we’d tried. Or maybe, I don’t know … we could try IVF.’

‘A bank-breaking emotional rollercoaster with no guarantees. The other day Honor interviewed a woman who’s spent forty thousand pounds on it and still isn’t pregnant.’

‘Well, we might be luckier. If not, we could adopt.’

‘Could we?’ I echoed. ‘Would we really want that? In any case this is all academic, because I won’t be changing my mind; and if you really do love me, you’ll accept that. Can’t we just go on as we were?’ I added desperately.

Rick blinked. ‘I don’t see how we can.’

My throat ached with a suppressed sob. ‘Why not? Because now you’ve decided that you would like kids, you’d want to go right out there, as soon as possible, and find some woman to have them with? Is that it? Should I start knitting a matinee jacket for the baby right now?’

Rick flinched. ‘Don’t be silly, Jen. It’s because we’d only be putting off the inevitable. I’d come to resent you, then you’d be upset with me, and we’d break up anyway.’ He shook his head. ‘What I don’t understand is why you won’t at least explore why it is that you feel—’

‘No,’ I interrupted. ‘I won’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I’m not prepared to bare my soul to some stranger! In any case there’s nothing to explore. Yes, lots of women want children, but there are lots who don’t, and I’m one of them. So seeing a counsellor won’t make any difference. I mean, you’re the one who’s changed, Rick, not me, yet you’re making the condescending assumption that I don’t know my own mind!’

‘No, Jen, I’m just trying to work out why you feel as you do. Because you like children. You go out of your way to be with them.’

‘That’s not true.’

‘It is – you come into school every week and read to them.’

‘I … do it for you.’

‘Jen …’ Rick looked bewildered. ‘That’s how we met.’

Another silence fell. I could hear a magpie chattering in a nearby garden. ‘Well, it’s hardly a big deal, especially as my flat was practically next door. And liking children doesn’t mean I want to have them myself. I don’t.’

‘Yet you’ve said that if I’d been divorced, with children, you’d happily have had those kids in your life.’

‘Yes.’

‘But you won’t have a child of your own.’

‘No.’

‘I wish I knew why not. If you told me that it was because you felt that having children would wreck your career, or your lifestyle, or your body, I could at least understand that. I could try to accept it. But to say that you won’t have children because you’d be too scared …’

I put my hand on the table, tracing the grain with my fingertips. ‘I would be,’ I insisted quietly.

‘Why?’

I looked up. ‘I’ve told you; I’d be scared that something would go wrong. Or that I’d make a terrible mistake – that I’d drop the baby, or forget to feed it or give it enough to drink.’

‘Babies don’t let you forget, Jen; that’s why they cry. And you’ve just written a book about babies. Hasn’t that made you feel you could cope?’

‘It’s given me knowledge of how to care for them,’ I conceded. ‘But it hasn’t taken away my fear that something bad would happen.’ Panic swept through me. ‘Like … cot death, God forbid; or that I’d turn my back for a few seconds – that’s all it would take – and the child would fall down the stairs, or run into the road, or that there’d be some terrible accident that I could never, ever, get over.’ Tears stung my eyes. ‘Parenthood’s a white-knuckle ride, and I don’t want to get on.’

Rick gave a bewildered shrug. ‘Most people probably feel the same way, but they control their fears: you let them govern your life. You’re normally so level-headed, but with this I think you’re being—’

‘Don’t tell me – irrational?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s not irrational to avoid anxiety and stress.’

‘It is irrational to presume that things will go terribly wrong – especially as you’ve no reason to think you wouldn’t be a good, careful parent. What’s your real fear, Jenni? That you wouldn’t love the child?’

‘On the contrary; I know that I would – which is precisely why I don’t want to have one.’

He groaned. ‘But you know, Jen, this isn’t just about whether or not we have a family.’

‘What do you mean?’

Rick gave a frustrated sigh. ‘We get on so well, Jen.’ I nodded. ‘We respect each other. We love being together, we talk easily – and we’re attracted to each other.’

‘We are,’ I agreed with a pang.

‘But you’re just not … open with me. Every time I ask you about your childhood you avoid my questions, or change the subject. And you never mention your mother, or explain why it is that you’re virtually estranged.’

‘I have explained.’

‘You haven’t – at least not in any way that I can understand. And as time’s gone on it’s bothered me more and more. This feeling I have, that although I love being with you, and desire you, I don’t really know you.’ He sighed. ‘You said that your mother neglected you.’

‘No. She looked after me. But she was distant and cold.’

‘That is neglect.’ Rick chewed his lip. ‘So … was she always like that?’

‘No.’ I saw my mother playing with me, reading to me. Holding my hand … ‘But as I grew older, it got worse; and it wasn’t as though I had a father to make up for it.’

‘Maybe that’s why she was so remote – though you’d think what happened might have brought her closer to you.’

‘Well … it didn’t.’

‘Is this the real reason why you don’t want kids?’ Rick asked. ‘Out of a fear that you’d be like that with your own child? Because you wouldn’t be, Jen.’

‘How do you know?’ I demanded bleakly. ‘I might be worse.’

‘Jenni, I wish that you’d at least talk to someone who might be able to help you overcome your fears.’

I laughed. ‘With a wave of their magic, psychotherapeutic wand? No. In any case, there’s nothing to resolve. I don’t want to have children. I like talking to them, and reading to them, and playing with them, and yes, I can see that having a child must in many ways be wonderful. But against that I set the never-ending, heart-wrenching anxiety of parenthood. I intend to protect myself from that.’

Rick stood up then walked over to the patio doors and unbolted them. He went out and sat on the wooden bench at the end of our small garden. After a moment he took a pack of cigarettes out of his breast pocket, lit one, released a nebula of smoke, then sat with his hands on his knees, head bowed.

I pushed back my chair, gathered up the manuscript, then went down the hall into my study. I dropped the pages beside the computer and sat staring at the darkened screen.

Three options … allowed to change … not open with me …

I heard an e-mail come in but ignored it. Was there any way Rick and I might resolve our problem? I refused to see a counsellor. I didn’t need counselling, and it would be more likely to destroy us than help us. Without thinking, I clicked the mouse and the screen flared into life.

I looked at the list of messages, desperate for distraction. The first three offered me laser lipo, cut-price hair extensions and fifty per cent off a pocket-sprung mattress. The fourth was headed Ghostwriting Enquiry and had been automatically forwarded from my website. It was from Nina’s godfather, Vincent Tregear. Surprised that he should contact me, I read it. It was a two-line message, asking me to call him. I was too upset to speak to him now. Instead, I opened the baby-guide document and stared listlessly at the screen, seeing the words, but not taking them in. Then I closed the document and, with an effort of will, I forced my mind away from Rick. I wiped my eyes, reached for the handset and dialled the number that Vincent had given.

After three rings the phone picked up, and I recognised Vincent’s voice.

He thanked me for getting back to him. ‘I know we hardly spoke at the wedding,’ he went on. ‘But I was very interested in what you were saying about writing memoirs. So I made a mental note of your website and last night I took a look at it and was impressed. The reason I’ve got in touch is because I’m wondering whether you might be able to help my mother write her memoirs.’

‘I see!’

‘She’s seventy-nine,’ he explained. ‘She’s in good health, and her memory’s fine. For years my brother and I have suggested that she write something about her life. She’s always been against the idea, but recently, to our surprise, she said that she would like to. But it won’t be easy as there are some parts of her life that she’s never talked about.’ Broken love affairs, I speculated, or marital difficulties. ‘She’s never talked about what happened to her during the war.’

My thoughts were racing, my mind already trying to shape a possible story for Vincent’s mother. She would have been a child at the time. Perhaps she’d lived in London, was evacuated, and was treated badly. Perhaps she’d stayed, and seen terrible things.

‘She doesn’t have a computer,’ I heard Vincent say. ‘So I offered to help her get her reminiscences onto paper; but she said that she’d find it too awkward, sharing such difficult memories with her own child.’

‘That’s completely understandable. I know I’d find it hard myself.’

‘So for a while we left it there; then last week, out of the blue, my mother suggested that we find someone for her to talk to. I thought about commissioning a journalist, but then at the wedding I heard you talking about what you do. So … how exactly would it work?’

I explained that I spend time with the person, and record hours of interviews with them. ‘With their permission I also read their diaries and correspondence,’ I went on. ‘I look at their photos and mementoes – anything that will help me to prompt their memories.’

‘Then you transcribe it all,’ he said.

‘Yes – except that it’s much more than a transcription. I’m trying to evoke that person, in their own voice. So I don’t simply ask them what happened to them, I ask them how they felt about it at the time; how they think their experiences changed them, what they’re proud of, or what they regret. It’s quite an intense exploration of who the person is and how they’ve lived – there’s a lot of soul-searching. Some people find it difficult.’

‘I can understand. And how long would it take?’

‘Three to four months. So … have a think,’ I added, still avidly wondering what his mother’s story might be.

‘I don’t need to think about it,’ Vincent responded. ‘I’m keen to go ahead. In fact I wanted to ask if you could start next week?’

‘That’s … soon.’

‘It is, but we’d like to have it done in time for my mother’s eightieth in late January. It’s to be our present to her.’

‘I see. Well, I’d have to check my work diary.’ I didn’t want to let on that there was precious little in it. ‘But before I do, could you tell me a bit more?’ I reached for a pad and pen, glad to have this distraction.

‘My mother’s farmed for most of her life.’ I scribbled farmer. ‘It’s not a big farm,’ he explained, ‘just a hundred and twenty acres; but it’s been in my father’s family since the 1860s. He died ten years ago.’

Widowed, I wrote. Farm. 150 yrs.

‘Mum has always worked very hard, and still works hard,’ Vincent went on. ‘She runs the farm shop and she grows most of what’s sold in it.’

‘And what sort of education did she have? Did she go to university?’

‘No. She married my father when she was nineteen.’

Married @ 19 … Mrs Tregear. ‘And what’s her first name?’ Vincent told me and I wrote it down. ‘That’s pretty.’

‘It’s Klara with a “K”.’

‘So … is your mother German?’

‘No. Dutch.’

As I turned the C into a K, I imagined Klara growing up in Holland, under German occupation. Perhaps she’d known Anne Frank, or Audrey Hepburn – they’d have been about the same age. I saw Klara standing in a frozen field trying to dig up tulip bulbs to eat.

‘My mother grew up in the tropics,’ I heard Vincent say. ‘On Java. Her father was the manager of a rubber plantation.’

Plantation … Java …

‘When the Pacific War started, after Pearl Harbor, she was interned with her mother and younger brother.’ Interned … I imagined bamboo fencing and barbed wire.

‘We know that internees suffered terrible privation, as well as cruelty, but she’s rarely talked about it, except to mention the odd incident in this camp or that.’

I’d have to do some research. I scribbled Dutch East Indies, then Japanese occupation.

‘Vincent, I would like to take on this commission.’

‘Really? That’s great!’

‘And in fact I could start next week.’ My pen had run out. I yanked open the drawer and rummaged in it for another one. ‘If you give me your address, I’ll send you my standard letter of engagement. Where do you live?’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.