Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The White House Connection»

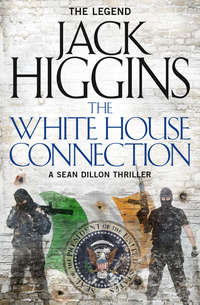

The White House Connection

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph 1999

Copyright © Harry Patterson 1999

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Photography and illustration © Nik Keevil

Harry Patterson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008124854

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780007384792

Version: 2015-04-01

To my mother-in-law, Sally Palmer. Thanks for the idea

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PROLOGUE NEW YORK

IN THE BEGINNING LONDON NEW YORK

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

LONDON WASHINGTON ULSTER

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

WASHINGTON NANTUCKET NEW YORK

Chapter 6

LONDON

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

NEW YORK WASHINGTON

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

LONG ISLAND NORFOLK

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

NORFOLK ULSTER

Chapter 15

EPILOGUE

Chapter 16

About the Author

Also by Jack Higgins

Further Reading

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

NEW YORK

Manhattan, with an east wind driving rain mixed with a little sleet along Park Avenue, was as bleak and uninviting as most great cities after midnight, especially in March. There was little traffic – the occasional limousine, the odd cab – hardly surprising at that time of the morning and with such uninviting weather.

In a stretch of mixed offices and residences, a woman waited in an archway, standing in the shadows, a wide-brimmed rain hat on her head and wearing a trenchcoat, the collar turned up. An umbrella was looped to her left wrist. She carried no purse or shoulder bag.

She felt for the gun in the right-hand pocket of her trenchcoat, took it out and checked it expertly by feel. It was an unusual weapon, a Colt .25 semiautomatic, eight-shot, relatively small but deadly, especially with the silencer on the end. Some people might have thought it a woman’s gun, but not when used with hollow-point cartridges. She replaced it in her pocket and looked out.

Slightly to her right on the other side of Park Avenue was a splendid townhouse. It was owned by Senator Michael Cohan, who was attending a fundraiser at the Pierre, a function due to finish at midnight, which was why she waited here in the shadows with the intention, all things being equal, of leaving him dead on the pavement.

She heard the sound of voices, a drunken shout, and two young men came round the corner on the other side and started along the sidewalk. They were dressed in identical woollen hats, reefer coats and jeans, and they were drinking from cans. One of them, tall and bearded, stepped into the flooded gutter and kicked water, grinning, but as the rain increased, the other one wrapped his jacket tighter. Spotting the entrance to a covered alley, he swallowed the rest of his beer and dropped the can into the gutter.

‘In here, man.’ He ran for the entrance.

‘Damn!’ the woman said softly. The alley was next to Cohan’s house.

There was nothing to be done. They had disappeared into the shadows, but she could hear them clearly, their laughter loud. She waited impatiently for them to move on, and then a young woman turned the same corner the men had come from and moved along the sidewalk. She was small, and, except for her umbrella, unsuitably dressed for such weather, in high heels and a black suit with a short skirt. She heard the raucous laughter, hesitated, then started past the alley.

A voice called, ‘Hey, where are you going, baby?’ And the bearded man stepped out, his friend following.

The girl started to hurry and the bearded man dashed after her and grabbed her arm. She dropped her umbrella and struggled and he slapped her across the face.

‘Fight as much as you want, sweetheart. I like it.’

His friend grabbed her other arm. ‘Come on, let’s get her inside.’

The girl cried out in terror and the bearded one slapped her again. ‘Now you be good.’

They dragged her into the alley. The older woman hesitated and then she heard a scream. ‘Damn!’ she said for the second time, stepped out into the rain and crossed over. It was dark in the alley, with only a little diffused light from the street lamp outside. The girl tried to struggle against the man holding her from behind, but the bearded man had a knife in his right hand and touched it to her cheek, drawing blood.

She cried out in pain and he said, ‘I told you to be good.’ He reached for the hem of her skirt and sliced upwards with the sharp blade, parting it. ‘There you go, Freddy. Be my guest.’

A calm voice said, ‘I don’t think so.’

Freddy’s face, as he looked beyond his friend, registered astonishment. ‘Jesus!’ he said.

The bearded man turned and found the woman standing in the alley entrance. She was carrying the rain hat in her right hand. Her hair was silvery white, highlighted by the back light from the street lamp. She looked to be in her sixties, but it was hard to tell anything about her face in the dark.

‘What the hell is this?’ the one holding the girl said.

‘Just let her go.’

‘I can’t tell you what she wants, but I know what she’s going to get,’ the bearded man said to his friend. ‘The same as this bitch. You feel like some company tonight, Grandma?’

He took a step forward and the woman shot him in the heart, firing through the rain hat, the sound muted. He was thrown against the wall, bounced off and fell on his back.

The girl was so terrified that she didn’t utter a word. It was the man holding her who reacted. ‘Jesus!’ he moaned. ‘Oh, God,’ and then he took a knife from his pocket and sprang the blade. ‘I’ll cut her throat,’ he said to the older woman, ‘I swear it.’

The woman stood there, the Colt in her right hand, down against her thigh now. Her voice, when she spoke, was still calm and controlled. ‘You never learn, you people, do you?’

Her hand swung up and she shot him between the eyes. He fell backwards. The girl leaned against the wall, breathing heavily, blood on her face. The woman removed her light woollen scarf and passed it across and the girl held it to her face. The woman leaned over, checked the bearded man first and then the other.

‘Well, neither of these gentlemen will be bothering anyone again.’

The girl exploded. ‘The bastards.’ She kicked the bearded man. ‘If you hadn’t come along.…’ She shuddered. ‘I hope they rot in hell.’

‘It’s a strong possibility,’ the woman said. ‘Do you live near here?’

‘About twenty blocks. I was having dinner at a place around the corner, had a fight with my date and walked out hoping to find a cab.’

‘You never can find one when it’s raining. Let me look at your face.’

She pulled the girl to the entrance. ‘I’d say you’ll need two or three stitches. St Mary’s Hospital is two blocks that way.’ She pointed. ‘Go to the emergency room. Tell them you had an accident. You slipped, cut your cheek, tore your skirt.’

‘Will they believe me?’

‘It doesn’t matter. It’s your business.’ The woman shrugged. ‘Unless you want to go to the police.’

‘Good God, no!’ the girl replied, a kind of agony there. ‘That’s the last thing I want.’

The woman stepped out, picked up the fallen umbrella and gave it to her. ‘Then go, my dear, and don’t look back. It didn’t happen, none of it.’ She stepped back and picked up the girl’s purse where it had fallen. ‘Don’t forget this.’

The girl took it. ‘And I won’t forget you.’

The woman smiled. ‘On the whole, I’d rather you did.’

The girl managed a small smile. ‘I see what you mean.’

She turned and hurried off, clutching the umbrella. The woman watched her go, examined the bullet hole in her hat, put it on, then opened her own umbrella and walked away in the opposite direction.

Two blocks north, she found the Lincoln parked at the kerb. The man behind the wheel was out and waiting for her as she approached, a large black man wearing a grey chauffeur’s suit.

‘You okay?’ he asked.

‘I’m here, aren’t I?’

She got into the front passenger seat. She closed the door, went round and got behind the wheel. She strapped herself in and tapped his shoulder. ‘Where’s that flask of yours, Hedley, the Bushmills whiskey?’

He took a silver flask from the glove compartment, unscrewed the cap and passed it to her. She swallowed once, twice, then handed it back.

‘Wonderful.’

She took out a silver case, selected a cigarette and lit it with the car lighter, then blew out a long stream of smoke. ‘All the bad habits are so pleasurable.’

‘You shouldn’t be doing that. It’s not good for you.’

‘Does it matter?’

‘Don’t say that.’ He was upset. ‘Did you get the bastard?’

‘Cohan? No, something got in the way. Let’s head back to the Plaza and I’ll tell you.’ She was finished by the time they were halfway there and he was horrified.

‘My God, what you trying to do? Clean up the whole world now?’

‘I see. You mean I should have stood by and waited while those two animals raped the girl and probably cut her throat?’

‘Okay, okay!’ he sighed and nodded. ‘What about Senator Cohan?’

‘We’ll fly back to London tomorrow. He’s due there in a few days, showing his face on what he pretends is Presidential business. I’ll get him then.’

‘And then what? Where does it end?’ Hedley grunted. ‘It all seems unreal.’

He pulled up at the Plaza and she smiled mischievously like a child. ‘I’m a great trial to you, Hedley, I know that, but what would I do without you? See you in the morning.’

He went round and opened the door for her and watched her go up the steps.

‘And what would I do without you?’ he asked softly, then got behind the wheel and drove away.

The night doorman was waiting at the top. ‘Lady Helen!’ he said. ‘It’s wonderful to see you. I heard you were in.’

‘And you, George.’ She kissed him on the cheek. ‘How’s that new daughter of yours?’

‘Great, just great.’

‘I’m going back to London in the morning. I’ll see you again soon.’

‘’Night, Lady Helen.’

She went in, and a man in a raincoat who had been waiting for a cab said, ‘Hey, who was that woman?’

‘Lady Helen Lang. She’s been coming here for years.’

‘Lady, huh? Funny, she doesn’t sound English.’

‘That’s ’cause she’s from Boston. Married an English Lord ages ago. People say she’s worth millions.’

‘Really? Well, she seems quite something.’

‘You can say that again. Nicest person you’ll ever meet.’

IN THE BEGINNING

1

Born in Boston in 1933 to one of Boston’s wealthiest families, Helen Darcy was raised as an only child as her mother had died giving birth to her. Fortunately, her father truly loved her and she loved him just as much in return. In spite of his enormous business interests in steel, shipbuilding and oil, he took the time to lavish every attention on her, and she was worth it. Enormously intelligent, she went to the best private schools, and later, Vassar, where she found she had a special flair for foreign languages.

To her father, only the best was good enough and, himself a Rhodes Scholar as a young man, he sent her to England to finish her graduate education at St Hugh’s College at Oxford University.

Many of her father’s business associates in London put themselves out to entertain her and she became popular in London society. She was twenty-four when she met Sir Roger Lang, a baronet and one-time lieutenant colonel in the Scots Guards, now chairman of a merchant bank with close associations with her father.

She adored him at once and the attraction was mutual. There was one flaw, however. Although he was unmarried, there was a fifteen years’ age difference between them and, at the time, it simply seemed too much for her.

She returned to America, confused and uncertain about the future, for business held no attraction for her and she’d had enough of academia. There were plenty of young men, of course, if only for the wrong reason – her father’s enormous wealth – but no one suited her, because in the background there was always Roger Lang, with whom she stayed in touch once a week by telephone.

Finally, one weekend at their beach house on Cape Cod, she said to her father across the breakfast table, ‘Daddy, don’t be mad at me, but I’m thinking of moving back to England…and getting married.’

He leaned back and smiled. ‘Does Roger Lang know about this?’

‘Dammit, you knew.’

‘Ever since you came back from Oxford. I was wondering when you’d come to your senses.’

She poured tea, a habit she’d acquired in England. ‘The answer is…he doesn’t know.’

‘Then I suggest you fly to London and tell him,’ and he returned to his New York Times.

And so, a new life began for Helen Darcy, now Lady Helen Lang, divided between the house in South Audley Street and the country estate by the sea in North Norfolk, called Compton Place. There was only one fly in the ointment. In spite of every effort to have a child, she was bedevilled by miscarriages year after year, so that by the time her son, Peter, was born when she was thirty-three, it seemed a major miracle.

Peter proved to be another great joy in her life, and she took the kind of interest in his education that her father had taken in hers. Her husband agreed he could go to an American prep school for a few years, but afterwards, as the future Sir Peter, he had to finish his education at Eton and the Sandhurst Military Academy. It was the family tradition – which was fine with Peter, for he had only ever wanted to be one thing, a soldier like all the Langs before him.

After Sandhurst came the Scots Guards, his father’s old regiment, and a few years later, a transfer to the SAS, for he had inherited his mother’s ability with languages. He saw service in Bosnia and in the Gulf War, where he was awarded the Military Cross for an unspecified black operation behind Iraqi lines. And in Ireland, of course, the one place which never went away. Hand-in-hand with his ability for languages was a flair for dialects. He spoke, not with some stage Irish accent, but as if he were from Dublin or Belfast or South Armagh, which made him invaluable for undercover work in the continuing battle with the Provisional IRA.

Because of the life he led, women figured little. The odd girlfriend now and then was all he had time for. The fear was real, the burden immense, but Helen bore it as a soldier’s wife and mother should, until that dreadful Sunday in March 1996, when her husband answered the phone at South Audley Street, then replaced the receiver slowly and turned, his face ashen.

‘He’s gone,’ he said simply. ‘Peter’s gone,’ and he slumped into a chair and cried his eyes out, while she held his hand and stared blankly into space.

If there was one person who understood her grief that rainy day in the churchyard of the village church of St Mary and All the Saints at Compton Place, it was Lady Helen Lang’s chauffeur, Hedley Jackson, who stood behind her and Sir Roger, immaculate in his grey uniform, as he held a large umbrella above them.

He was six feet four and originally from Harlem. At the age of eighteen, he’d joined the Marine Corps and gone to Vietnam, emerging at the other end with a Silver Star and two Purple Hearts. Posted to the American Embassy Guard in London, he’d met a girl from Brixton who was housekeeper to the Langs at South Audley Street. They had married, Hedley had left the service and been appointed the Langs’ chauffeur, and they had lived in the spacious basement flat and had a child, a son. It was an ideal life for them, and then tragedy struck: Jackson’s wife and son were involved in a multi-car pile-up in the fog on the North Circular Road, and were killed instantly.

Lady Helen had held his hand at the crematorium, and when he had disappeared from South Audley Street, she had hunted him down through one bar after another in Brixton until she found him, sodden with drink and nearly suicidal, had taken him to Compton Place, and slowly, patiently, brought him back to life.

To say that he was devoted to her now was an understatement, and his heart bled for her, particularly since Sir Roger’s words to her, ‘Peter’s gone,’ had hidden a horrific truth. The IRA car bomb which had killed him had been of such enormous strength that not a single trace of his body remained, and, standing there in the rain, all they could commemorate was his name engraved in the family mausoleum.

MAJOR PETER LANG, MC,

SCOTS GUARDS, SPECIAL AIR SERVICE REGIMENT

1966–1996

REST IN PEACE

Helen held her husband’s hand. He had aged ten years in the past few days – a man once spry and vigorous now seemed as if he’d never been young. Rest in peace, she thought. But that’s what it was supposed to have been for. Peace in Ireland, and those bastards destroyed him. No trace. It’s as if he’s never been, she thought, frowning, unable to weep. That can’t be right. There’s no justice, none at all in a world gone mad. The priest intoned: ‘I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord.’

Helen shook her head. No, not that. Not that. I don’t believe any more, not when evil walks the earth unpunished.

She turned, leaving the astonished mourners, taking her husband with her, and walked away. Hedley followed, the umbrella held over them.

Her father, unable to attend the funeral because of illness, died a few months later, and left her a millionaire many times over. The management team that controlled the various parts of the corporation were entirely trustworthy and headed by her cousin, with whom she’d always been close, so it was all in the family. She devoted herself to her husband, a broken man, who himself died a year after his son.

As for Helen, she gave a certain part of her activities to charitable work and spent a great deal of time at Compton Place, although the one thousand acres that went with the house were leased out for large-scale farming.

To a certain extent, Compton Place was her salvation because of its fascinating location. A mile from the coast of the North Sea, that part of Norfolk was still one of the most rural areas of England, full of winding narrow lanes and places with names like Cley-next-the-Sea, Stiffkey and Blakeney, little villages found unexpectedly and then lost, never to be found again. It was all so timeless.

From the first time Roger had taken her there, she had been enchanted by the salt marshes with the sea mist drifting in, the shingle and sand dunes and the great wet beaches when the tide was out.

From her days as a child growing up in Cape Cod, she had loved the sea and birds and there were birds in plenty in her part of Norfolk: Brent geese from Siberia, curlews, redshanks and every kind of seagull. She loved walking or cycling along the dykes, none of them less than six feet high, that passed through the great banks of reeds. It gave her renewed energy every time she breathed in the salt sea air or felt the rain on her face.

The house had originally been built in Tudor times, but was mainly Georgian with a few later additions. The large kitchen was a post-war project, lovingly created in country style. The dining room, hall, library, and the huge drawing room, were panelled in oak. There were only six bedrooms now, for others had been developed into bathrooms or dressing rooms at various stages.

With the estate leased to various farmers, she had retained only six acres around the house, mainly woodland, leaving two large lawns and another for croquet. A retired farmer came up from the village from time to time to keep things in order, and when they were in residence, Hedley would get the tractor out and mow the grass himself.

There was a daily housekeeper named Mrs Smedley, and another woman from the village helped her with the cleaning when necessary. All this sufficed. It was a calm and orderly existence that helped her return to life. And the villagers helped, too.

The laws of the British aristocracy are strange. As Roger Lang’s wife, she was officially Lady Lang. Only the daughters of the higher levels of the nobility were allowed to use their Christian names, but the villagers in that part of Norfolk were a strange, stubborn race. To them she was Lady Helen, and that was that. It was an interesting fact that the same attitude pertained in London society.

Any help anyone needed, she gave. She attended church every Sunday morning and Hedley sat in the rear pew, always correctly attired in his chauffeur’s uniform. She was not above visiting the village pub of an evening for a drink or two, and there, too, Hedley always accompanied her and, though you might not think it, was totally accepted by those taciturn people ever since an extraordinary event some years past.

An incredibly high tide combined with torrential rain had caused the water to rise in the narrow canal that passed through the village from the old disused mill. Soon, it was overflowing into the street and threatening to engulf the village. All attempts to force open the lock gate which was blocking the water proved futile, and it was Hedley who plunged chest deep into the water with a crowbar, diving under the surface again and again until he managed to dislodge the ancient locking pins and the gate burst open. At the pub, he had never been allowed to pay for a drink again.

So, although it had lost its savour, life could have been worse – and then Lady Helen received an unexpected phone call, one that in its consequences would prove just as catastrophic as that other call two years earlier, the call that had announced the death of her son.

‘Helen, is that you?’ The voice was weak, yet strangely familiar.

‘Yes, who is this?’

‘Tony Emsworth.’

She remembered the name well: a junior officer under her husband many years ago, later an Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office. She hadn’t seen him for some time. He had to be seventy now. Come to think of it, he hadn’t been at either Peter’s funeral or her husband’s. She’d thought that strange at the time.

‘Why, Tony,’ she said. ‘Where are you?’

‘My cottage. I’m living in a little village called Stukeley now, in Kent. Only forty miles from London.’

‘How’s Martha?’ Helen asked.

‘Died two years ago. The thing is, Helen, I must see you. It’s a matter of life and death, you could say.’ He was racked by coughing. ‘My death, actually. Lung cancer. I haven’t got long to go.’

‘Tony. I’m so sorry.’

He tried to joke. ‘So am I.’ There was an urgency in his voice now. ‘Helen, my love, you must come and see me. I need to unburden myself of something, something you must hear.’

He was coughing again. She waited until he’d stopped. ‘Fine, Tony, fine. Try not to upset yourself. I’ll drive down to London this afternoon, stay overnight in town, and be with you as soon as I can in the morning. Is that all right?’

‘Wonderful. I’ll see you then.’ He put down the phone.

She had taken the call in the library. She stood there frowning, slightly agitated, then opened a silver box, took out a cigarette and lit it with a lighter Roger had once given her made from a German shell.

Tony Emsworth. The weak voice, the coughing, had given her a bad shake. She remembered him as a dashing Guards captain, a ladies’ man, a bruising rider to hounds. To be reduced to what she had just heard was not pleasant. Intimations of mortality, she thought. Death just round the corner, and there had been enough of that in her life.

But there was another, secret reason, something even Hedley knew nothing about. The odd pain in the chest and arm had given her pause for thought. She’d had a private visit to London recently, a consultation with one of the best doctors in Harley Street, tests and scans at the London Clinic.

It reminded her of a remark Scott Fitzgerald had made about his health: ‘I visited a great man’s office and emerged with a grave sentence.’ Something like that. Her sentence had not been too grave. Heart trouble, of course. Angina. No need to worry, my dear, the professor had said. You’ll live for years. Just take the pills and take it easy. No more riding to hounds or anything like that.

‘And no more of these,’ she said softly, and stubbed out the cigarette with a wry smile, remembering that she’d been saying that for months, and went in search of Hedley.

Stukeley was pleasant enough: cottages on either side of a narrow street, a pub, a general store and Emsworth’s place, Rose Cottage, on the other side of the church. Lady Helen had phoned before leaving London to give him the time and he was expecting them, opening the door to greet them, tall and frail, the flesh washed away, the face skull-like.

She kissed his cheek. ‘Tony, you look terrible.’

‘Don’t I just?’ He managed a grin.

‘Should I wait in the Merc?’ Hedley asked.

‘Nice to see you again, Hedley,’ Emsworth said. ‘Would it be possible for you to handle the kitchen? I let my daily go an hour ago. She’s left sandwiches, cakes and so on. If you could make the tea.…’

‘My pleasure,’ Hedley told him, and followed them in.

A log fire was burning in the large open fireplace in the sitting room. Beams supported the low ceiling and there was comfortable furniture everywhere and Indian carpets scattered over the stone-flagged floor.

Emsworth sat in a wing-backed chair and put his walking stick on the floor. A cardboard file was on the coffee table beside him.

‘There’s a photo over there of your old man and me when I was a subaltern,’ he said.

Helen Lang went to the sideboard and examined the photo in its silver frame. ‘You look very handsome, both of you.’

She returned and sat opposite him. He said, ‘I didn’t attend Peter’s funeral. Missed out on Roger’s, too.’

‘I had noticed.’

‘Too ashamed to show my face, ye see.’

There was something here, something unmentionable that already touched her deep inside, and her skin crawled.

Hedley came in with tea things on a tray and put them down beside her on a low table. ‘Leave the food,’ she told him. ‘Later, I think.’

‘Be a good chap,’ Emsworth said. ‘There’s a whisky decanter on the sideboard. Pour me a large one and one for Lady Helen.’

‘Will I need it?’

‘I think so.’

She nodded. Hedley poured the drinks and served them. ‘I’ll be in the kitchen if you need me.’

‘Thank you. I think I might.’

Hedley looked grim, but retired to the kitchen. He stood there thinking about it, then noticed the two doors to the serving hatch and eased them ajar. It was underhanded, yes, but all that concerned him was her welfare. He sat down on a stool and listened.

‘For years I lived a lie as far as my friends were concerned,’ Emsworth said. ‘Even Martha didn’t know the truth. You all thought I was Foreign Office. Well, it wasn’t true. I worked for the Secret Intelligence Service for years. Oh, not in the field. I was the kind of office man who sent brave men out to do the dirty work who frequently died doing it. One of them was Major Peter Lang.’

There was that crawling feeling again. ‘I see,’ she said carefully.

‘Let me explain. My office was responsible for black operations in Ireland. The people we were after were not only IRA, but Loyalist paramilitaries who, because of threats and intimidation of witnesses, escaped legal justice.’

‘And what was your solution?’

‘We had undercover groups, SAS in the main, who disposed of them.’

‘Murdered, you mean?’

‘No, I can’t accept that word. We’ve been at war with these people for too many years.’

She didn’t pour the tea, but reached for the whisky and sipped some. ‘Am I to understand that my son did such work?’

‘Yes, he was one of our best operatives. Peter’s ability to turn on a range of Irish accents was invaluable. He could sound like a building site worker from Derry if he wanted to. He was part of a group of five. Four men, plus a woman officer.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.