Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter», sayfa 2

This was the city Frank Graves ran from 1960 to 1966. Despite the deteriorating economy, the mayor wanted the police force to be his legacy. Graves himself was a policeman manqué. He had ridden in police cars as a kid and relished the crisp blue uniforms, the recondite radio codes, and the peremptory wail of a car siren. But his father, Frank X. Graves, Sr., would not allow his son to work on the force. Frank Sr. was a city power broker who owned a lucrative cigarette vending-machine company. He also covered the police for the Paterson Evening News for fifty years, and no son of his was going to chase petty thieves on the street. So, as mayor, Frank Jr. gloried in turning the police into his fiefdom. He spent time at the police station and personally answered incoming calls. He approved all hires, assignments, and promotions. He interrogated suspects. He chastised traffic cops who failed to direct cars with sufficient authoritarian snap. He required patrolmen to salute him, and offenders were summoned to the captain’s office the next day for a reprimand. Graves decreed that all police calls receive a response within ninety seconds, resulting in siren-blaring patrol cars careening through Paterson’s narrow streets. “The police force,” Graves said, “is the city.” And no task was too trivial. He once sent a phalanx of patrol cars to a nearby suburb to search for Tiger, a dog who’d strayed from Paterson.

But Graves came under fire for turning the city into a police state; there were charges of brutality and even torture. In 1964 the state ordered Passaic County to convene a grand jury to investigate reports that Paterson police had burned a prisoner’s body with matches and poured alcohol into his nose. The grand jury made no indictments but recommended that the department photograph prisoners both before and after questioning. The barroom raids were seen as grandstanding ploys, sacrificing basic patrol work. Although drug-related crimes were the city’s worst problem, there was only one man in the Narcotics Bureau.

Paterson’s swelling black population especially feared the mostly white police force and resented Graves’s apparent indifference to their grievances. During the Depression, blacks made up less than 2 percent of the city’s population. By the middle 1960s, they were about 20 percent. Between 1950 and 1964, 18,000 blacks and Hispanics moved into Paterson as 13,000 whites moved out. At the same time, good factory jobs were disappearing quickly, creating tensions between whites and blacks for a piece of the shrinking economic pie. Many black immigrants settled in the Fourth Ward and established taverns and nightclubs. Housing there was a shambles. Old wooden structures slouched beneath the weight of their new occupants; many of the units lacked plumbing, central heating, or private baths. A citywide survey showed that when a black family moved into a tenement, the rent was increased. There were long waiting lists for low-income municipal housing, and when blacks tried to move out of the Fourth Ward, they were refused or stalled by white real estate agents. Health conditions were horrid. A protest group offered a bounty of ten cents for each rat found in a home and delivered to City Hall. A court injunction snuffed out the rodent rebellion.

The anger in the black community was finally unleashed in August 1964, when a three-day riot broke out, primarily in the Fourth Ward. No one was killed, but the cataract of violence unnerved white Patersonians, who still made up 75 percent of the city’s 140,000 residents. Black youths shattered more than a dozen store windows at the intersection of Godwin and Graham Streets while a black youngster battling sixteen policemen was pushed through a plate glass window. Factory fires, Molotov cocktails, and errant shotgun blasts sent panic through the city. A marked law enforcement car from Maryland appeared with two German shepherd police dogs, although the authorities said they were never loosed on the rioters. Black leaders blamed the uprising on police harassment and overcrowded housing conditions, saying it was simply too hot to stay indoors, and they demanded rent control in blighted areas and a new police review board.

The riot was part of a summer of uprisings that broke out in Harlem, in Jersey City and Elizabeth, New Jersey, in Rochester, New York, and in small black enclaves in Oregon and New Hampshire. In each case, a street arrest triggered escalating hostilities, but only Paterson had Frank Graves.

The mayor tried to keep control. At a luncheon in Paterson on August 12 for Miss New Jersey, he promised, “Paterson will be completely safe for you tonight.” By nightfall, Graves probably hoped, Miss New Jersey was smiling in some other part of the state, because violence erupted once again in Paterson. Graves personally led the police through a ravaged ten-block area and narrowly missed serious injury when a bottle was thrown at him as he stepped from his car. Confronted by the overturned vehicles, shattered storefronts, and broken streetlights, Graves blamed the riot on “the worst hooligans that man has ever conceived.” His rhetoric, combined with his hard-nosed police, left little doubt among blacks that Graves was less interested in civil rights than civil repression.

Thoughts of race and crime were probably not on the mind of seventeen-year-old William Metzler when he arrived at work on Thursday, June 16, 1966. Metzler was an attendant for his father’s ambulance company in Paterson, working a midnight–8 A.M. shift. Employees stayed awake for two-hour stretches, sipping coffee, eating doughnuts, and monitoring the police radio. Some time after 2 A.M. on June 17, Metzler began hearing a series of police calls amid escalating panic. One call said, “Holdup.” Another: “Shooting.” And yet another, “Code one for ambulances,” which meant emergency.

Metzler and his older brother, Walt, raced their ambulance twelve blocks to the scene of the crime: the Lafayette Grill at 128 East Eighteenth Street, a nondescript neighborhood bar on the first floor of a tired three-story apartment building. When the ambulance arrived, a police car and two officers were on the site. William Metzler opened the bar’s side door, on Lafayette Street, walked inside, and literally slid across the bloody tile floor, almost falling into the red stream. Amid the cigarette and nut machines, a pool rack and jukebox and black-and-white television above the L-shaped bar, a scene of mayhem emerged: there were four bullet-ridden bodies—two dead, two alive, all white. It was, Metzler said years later, “a Wild West scene.”

While the shooting itself would be subject to one of the longest, most bitterly contested criminal proceedings in American history, no one would ever dispute the distinctively sadistic nature of the rampage. These basic facts were known within days.

Two black men entered the bar through the side door, one carrying a 12-gauge shotgun, the other a .32-caliber handgun. The bartender, James Oliver, age fifty-one, flung an empty beer bottle at the assailants, then turned to run. As the bottle shattered futilely against the wall, a single shotgun blast from seven feet away ripped through Oliver’s lower back, opening a two-by-one-inch hole. The bullet severed his spinal column, literally breaking the man in half. Oliver fell behind the bar, dead, two bottles of liquor lying near his tangled feet and cash strewn on the floor.

At about the same time the second assailant, holding the handgun, fired a single bullet at Fred Nauyoks, a sixty-year-old regular sitting on a barstool. The bullet ripped past Nauyoks’s right earlobe and struck the base of his brain, killing him instantly. He slumped over as if asleep, his head lying in a pool of blood, a lit cigarette between his fingers, his shot glass full, and cash on the bar ready to pay for the fresh drink. His foot remained on the stool’s footrest.

The pistol-carrying gunman then fired a bullet at William Marins, a forty-three-year-old machinist who had been at the bar for many hours, sitting two stools down from Nauyoks. The bullet entered his head near the left temple, caromed through the skull, and exited from the forehead by the left eye. He survived his wound and was able to describe the assailants to the police.

Seated in a different section of the bar was fifty-one-year-old Hazel Tanis, who had just arrived from her waitressing job at the Westmount Country Club. The assailant with the shotgun fired a single blast into her upper right arm. Then the second shooter turned and emptied his remaining five bullets, the muzzle of the gun as close as ten inches from the victim. Four bullets struck their mark: the right breast, the lower abdomen, the vagina, and the genital area. Tanis survived and was able to describe the gunmen to the police, but she developed an embolism four weeks later and died.

From the outset, the Lafayette bar murders became intertwined with another brutal homicide in Paterson. About six and a half hours earlier, a white man named Frank Conforti walked into the Waltz Inn, about four blocks from the Lafayette. Conforti had sold the bar to a black man, Roy Holloway, who was paying him in weekly installments. On this night, Conforti came to collect his last payment, but a heated argument broke out over the amount owed. Conforti stormed out of the tavern and returned moments later with a double-barreled shotgun. He blasted Holloway in the upper right arm; when Holloway tried to flee, he fired again, this time striking him in the head. Conforti was arrested for murder.

The police immediately suspected that the Lafayette bar shooting was in retaliation for the Waltz Inn murder. At the Waltz Inn, a white man with a shotgun killed a black bartender. At the Lafayette bar, a black man with a shotgun killed a white bartender. An eye for an eye. The Lafayette bar slaying chilled the white establishment. Black vigilantism, of course, was unacceptable. What’s more, the bar itself had long been a tiny neighborhood hangout for the Italians, Lithuanians, Poles, and other Eastern European immigrants who lived on the southern boundary of the working-class Riverside section.

But by the summer of 1966, the neighborhood was changing quickly. Blacks, moving north along Carroll and Graham Streets, were now living near and around the Lafayette bar. But the bar was still a watering hole for its traditional base of white workers, not blacks. Indeed, rumors circulated that the bartender refused to serve blacks. In time the bar, under different owners and different names, would be a black gathering spot for a black neighborhood. But on June 17, 1966, it was seen as a white redoubt against a coming black wave.

For a city the size of Paterson, the Lafayette bar shootings—four innocent victims, including one woman, three ultimately dead—would have been jarring under any circumstance. There had been only six murders in Paterson since the beginning of the year. But the overlay of race, of black invaders and white flight and a hapless neighborhood bar with a neon Schlitz sign and threadbare pool table, elevated the tragedy further.

Frank Graves assigned 130 police officers (out of a force of 341) to the investigation, promising promotions and three-month vacations to the arresting officers. He initially offered a $1,000 reward for information that led to an arrest, then raised it to $10,000. The Paterson Tavern Owners Association chipped in another $500. That the crime occurred in a bar confirmed the mayor’s conviction that taprooms were whirlpools of disorder. “We have three hundred and fifty” taverns, Graves thundered. “We should only have a hundred.”

He repeatedly referred to the Lafayette bar murders as “the most heinous crimes” and “the most dastardly crimes in the city’s history.” Two days after the shooting, Graves told the Paterson Evening News, “We will stay on this investigation until it is solved. There will be no such thing as a dead end in this case. If we hit a roadblock, we’ll back up and get on the main road until it is solved. These are by far the most brutal slayings in the city’s history.”

The pressure to solve the worst crime in Paterson’s long history would soon lead to the most feared man in the town.

3

DANGER ON THE STREETS

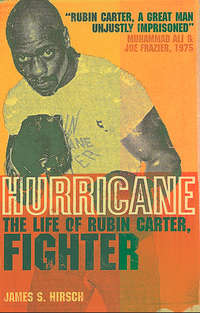

AT THE TIME of the Lafayette bar murders, Rubin Carter was a twenty-nine-year-old prizefighter and one of the great character actors of boxing’s golden era. The middleweight stalked opponents across the ring with a menacing left hook, a glowering stare, and a black bullet of a head—clean-shaven, with a sinister-looking mustache and goatee. Outside the ring, Carter cultivated a parallel reputation of a dashing but defiant night crawler. He settled grudges with his fists and was not cowed by the police. His intimidating style sent chills through boxing foes and cops alike, making him a target for both.

Regardless of where he walked, Carter always turned heads. At five feet eight inches and 160 pounds, he had an oversize neck, broad shoulders, and trapezoidal chest, with contoured biceps, thick hands, a tapering waist, and sinuous legs. A broadcaster once said of Carter, “He has muscles that he hasn’t even rippled yet.”

He was obsessed with fine clothing and personal hygiene, passions he inherited from his father. Lloyd Carter, Sr., believed that immaculate apparel showed a black man’s success in a white man’s world. A Georgia sharecropper’s son with a seventh-grade education, Lloyd earned a good living as a resourceful and indefatigable entrepreneur. He owned an icehouse, a window-washing concern, and a bike rental shop, and he wore his success proudly. He had his double-breasted suits custom-made in Philadelphia, favored French cuffs, and wore Stacy Adams two-tone alligator shoes. He bought his children shoes for school and for church; but if the school shoes had a hole, church shoes could not be worn to classes. No child of his would enter a house of worship with scuffed footwear.

Rubin Carter was just as meticulous as his father, if somewhat flashier. He instructed a Jersey City tailor to design his clothes to fit his top-heavy body. He placed $400 suit orders on the phone—“Do you have any new fabrics? … Good. Put it together and I’ll pick it up”—and he favored sharkskin suits, or cotton, silk, all pure fabrics, an occasional vest, and iridescent colors. His pants were pressed like a razor blade. He wore violet and blue berets pulled rakishly over his right ear, polished Italian shoes, and loud ties.

Carter trimmed his goatee with precision and clipped his fingernails to the cuticle. He collected fruit-scented colognes while traveling around the United States, Europe, and South Africa, then poured entire bottles into his bath water, soaked in the redolent tub, and emerged with a pleasing hint of nectar. Every three days Carter mixed Magic Shave powder with cold water and slathered it on his crown and face. He scraped it off with a butter knife, then rubbed a little Vaseline on top for a shine. His wife, Tee, complained that the pasty concoction smelled like rotten eggs, so she made him shave on their porch, but the result was Carter’s riveting signature: a smooth, shiny dome.

Nighttime was always Carter’s temptress, a lure of sybaritic pleasures and occasional danger. On his nights out, he left his wife at home and cruised through the streets of Paterson in a black Eldorado convertible with “Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter” emblazoned in silver letters on each of the headlights. He strolled into nightclubs with a wad of cash in his pocket and a neon chip on his shoulder. He bought everyone a round or two of drinks and mixed easily with women, both white and black. An incorrigible flirt, he danced, drank, and cruised with different women most every night.

But club confrontations often got Carter in trouble. He faced assault charges at least twice for barroom clashes, including once from the owner of the Kit Kat Club. Carter, contending he was unfairly singled out because of his swaggering profile, was cleared. But stories swirled about his hair-trigger temper. In an oft-repeated tale, Carter once found a man sitting at his table at the Nite Spot. When the man was slow to leave Hurricane’s Corner, Carter knocked him out with a punch, then took his girl.

Carter pooh-poohs such tales, although he says he would have told the man to sit elsewhere if other tables had been available. His dictum was that he never punched anyone unless first provoked, but he acknowledges that he was easily antagonized and, once aroused, showed little mercy on his tormentor. Adversaries came in all stripes. He once knocked a horse over with a right cross. The horse had had it coming: it tried to take a bite out of Carter’s side. The knockdown, publicized in local and national publications, added to Carter’s street-fighter reputation and legendary punching prowess.

Hedonistic excess was hardly uncommon in the boxing world; nonetheless, it was not widely known that Carter was an alcoholic during his career. Some thought Carter drank to make up for his dry years in prison: between 1957 and 1961, Carter had been sentenced to Trenton State Prison for assault and robbery. The inmates surreptitiously made a sugary wine concoction, “hooch,” but good liquor was hard to come by.

Outside prison, vodka was Carter’s drink of choice. Straight up, on the rocks, in a plastic cup, in a glass, from a bottle, it didn’t matter; it just had to be vodka. He was not a binge drinker but a slow, relentless sipper, and he could drink a fifth of vodka in a single night. Carter stayed clear of the bottle, mostly, when in training, but when he was out of camp, he kept at least one bottle of 100-proof Smirnoff’s in his car; friends hitching a ride got free drinks.

Carter concealed his drinking as much as possible. It was a sign of weakness and undermined his image as an athletic demigod. To avoid drinking in clubs, he picked up liquor in stores and drank in his car, sometimes with drinking buddies, sometimes alone. He tried not to order more than one drink at any one club on a given night. His wife rarely saw him imbibe and had no idea of the scope of his addiction. He carried Certs and peppermint candies to mask the alcohol on his breath, and he never got staggering drunk.

While Carter was a dedicated night owl, he was also a celebrity loner whose ready scowl stirred fear in bystanders, and he shunned close personal ties. He was often silent and moody, and many blacks in Paterson viewed him with a mixture of respect, envy, and fear. “Everybody loved Rubin, but no one was his friend,” said Tariq Darby, a heavyweight boxer from New Jersey in the 1960s. “I remember seeing him once in that black and silver Cadillac. He just turned and gave me that nasty look.”

Tensions were more overt between Carter and Paterson’s white majority as he flaunted his success in ways that he knew would tweak the establishment. He owned a twenty-six-foot fishing boat with a double Chrysler engine, which was docked at a marina in central New Jersey. He owned a horse, a once-wild mare he named Bitch, and rode in flamboyant style on Garrett Mountain. Dressed in a fringed jean jacket, a ten-gallon hat, and spur-tipped boots, Carter was hard to miss passing the white families picnicking on the hillside, and he didn’t mind when his riding partner was a white woman.

Carter’s shaved head, at least twenty-five years before bald pates became a common fashion statement among African Americans, had its own political edge. In the early 1960s, many blacks used lye-based chemical processors to straighten their curls and make their hair look “white.” White was cool. But Carter’s coal-black cupola sent a message: he had no interest in emulating white people. In fact, he shaved his head in part to mimic another glabrous black boxer, Jack Johnson, who won the heavyweight title in 1908 but was reviled as an insolent parvenu who drove fancy cars, drank expensive wines through straws, consorted with white women, and defied the establishment.

Carter’s showy displays jarred white Patersonians, who had a very different model for how a black professional athlete should act. They cherished Larry Doby, a hometown hero and baseball pioneer. On July 5, 1947, Doby joined the Cleveland Indians, breaking the color barrier in the American League. He was the second black major league player, following Jackie Robinson by eleven weeks. This feat spoke well of Doby’s hometown, Paterson, and Doby seemed to always speak well of the city. Never mind that Doby, who grew up literally on the wrong side of the Susquehanna Railroad tracks, knew well the racism of Paterson. As a kid going to a movie or vaudeville show at the Majestic Theater, he had to sit in the third balcony, known as “nigger heaven,” and he could not walk through white sections of Paterson at night without being stopped by police. Even after he became a baseball star, Doby was thwarted by real estate brokers from buying a home in the fashionable East Side of Paterson. He eventually moved his family to an integrated neighborhood in the more enlightened New Jersey city of Montclair.

But in public Doby was always a paragon of humility and deference. After he helped the Indians win the World Series in 1948, he was feted in Paterson with a motorcade. A crowd of three thousand gathered at Bauerle Field in front of Eastside High School, his alma mater, and city dignitaries gave effusive speeches about a black man whose deeds brought glory to their town. Then Doby took the microphone: he thanked the mayor and his teachers and coaches, concluding with these words: “I know I’m not a perfect gentleman, but I always try to be one.”

No white authority figure in Paterson ever called Rubin Carter a gentleman, perfect or otherwise. He was viewed not simply as brash and disrespectful but as a threat. Bad enough that he could knock down a horse with a single punch. Carter also owned guns, lots of them—shotguns, rifles, and pistols. He learned to shoot as a boy, practicing on a south New Jersey farm owned by his grandfather, and he honed his skills as a paratrooper for the 11th Airborne in the U.S. Army. He used his guns mostly for target practice but also for hunting, roaming the New Jersey woodlands with his father’s coon dogs. Carter could nail a treebound raccoon right between the eyes. He also owned guns for protection, and he had some of his suits tailored wide around the breast to accommodate a holster and pistol, which he would wear when he feared for his safety.

Like Malcolm X, Carter advocated that blacks use whatever means necessary, including violence, to protect themselves. He participated in the March on Washington in 1963, but two years later he rebuffed Martin Luther King, Jr.’s request to join a demonstration in Selma, Alabama. Carter knew he would not, could not, sit idly in the face of brutal attacks from law enforcement officials, white supremacists, or snarling dogs. “No, I can’t go down there,” he told King. “That would be foolishness at the risk of suicide. Those people would kill me dead.”

Carter did not accept the mainstream civil rights approach of passive resistance. He believed the sacrifices that blacks were making, whether on the riot-torn streets of Harlem or in the bombed-out churches of Birmingham, were unacceptable. Malcolm X had been killed. So too had James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three young civil rights workers, Medgar Evers, a black civil rights leader, and others unknown. Nonviolence is Gandhi’s principle, but Gandhi does not know the enemy, Carter thought.

When under attack, Rubin Carter believed in fighting back; in his view it was the police who were usually doing the attacking. But his many scrapes with the cops, plus some intemperate comments to a reporter, gave the authorities reason to believe that he was able, even likely, to commit a heinous crime.

In addition to the assault and robbery conviction in 1957, Carter, at fourteen, and three other boys attacked a Paterson man at a swimming hole called Tubbs near Passaic Falls. The man was cut with a soda water bottle and his $55 watch was stolen. Carter was sentenced to the Jamesburg State Home for Boys, but he escaped two years later. In the 1960s, his fracases with the police were common. In one incident, on January 16, 1964, a white officer picked him up after his Eldorado had broken down on a highway next to a meatpacking factory near Hackensack, New Jersey. He was driven to the town’s police headquarters, then accused of burglarizing the factory during the night. He had been locked in a holding cell for four hours when a black officer arrived and recognized him. “Is that you in there, Carter? What the hell did you get busted for, man?” Carter let out a stream of invective about the cops’ oppressive behavior. He was finally released after the black officer demanded to know the grounds on which he was being held. According to the official record, Carter had been arrested as a “disorderly person” for his “failure to give good account,” and the charge against him was dismissed.

Hostilities between Carter and the police, in New Jersey and elsewhere, escalated to a whole other level after a Saturday Evening Post article was published in October 1964. The story was a curtain raiser for the upcoming middleweight championship fight between the challenger, Carter, and Joey Giardello, the champ. The article, which introduced Carter to many nonboxing fans, was headlined “A Match Made in the Jungle.” Actually, the bout was to take place in Las Vegas, but “Jungle” referred to Carter’s feral nature. He was described as sporting a “Mongol-style mustache” and appearing like a “combination of bop musician and Genghis Khan.” With Carter fighting for the crown, “once again the sick sport of boxing seems to have taken a turn for the worse,” the article intoned. Giardello, photographed playfully holding his two young children, was the consummate family man. Carter sat alone, staring pitilessly into the camera.

In his interview with the sportswriter Milton Gross, Carter raged against white cops’ occupying black neighborhoods in a summer of unrest, and he exhorted blacks to defend themselves, even if it meant fighting to their death. He told the reporter that blacks were living in a dream world if they thought equality was around the corner, that reality was trigger-happy cops and redneck judges.

That part of the interview, however, was left out of the article. Instead, Gross printed his reckless tirade so that it was Carter, not the police, who looked liked the terrorist. Describing his life before he became a prizefighter, Carter told the writer: “We used to get up and put our guns in our pockets like you put your wallet in your pocket. Then we go out in the streets and start shooting—anybody, everybody. We used to shoot folks.”

“Shoot at folks?” Carter was asked, because this seemed too much to believe and too much for Carter to confess even years later.

“Just what I said,” he repeated. “Shoot at people. Sometimes just to shoot at ’em, sometimes to hit ’em, sometimes to kill ’em. My family was saying I’m still a bum. If I got the name, I play the game.”

This was sheer bluster on Carter’s part—no one had ever accused him of shooting anyone—but it was how he tried to rattle his boxing opponents and shake up white journalists. He invented a childhood knifing attack “I stabbed him everywhere but the bottom of his feet”—and the story quoted a friend of Carter’s who recounted a conversation with the boxer following a riot in Harlem that summer. The uprising occurred after an off-duty police lieutenant, responding to a confrontation between a sharp-tongued building superintendent and black youths carrying a bottle, shot to death a fifteen-year-old boy. Carter, according to his friend, said: “Let’s get guns and go up there and get us some of those police. I know I can get four or five before they get me. How many can you get?”

This fulsome remark sealed his image for the police and now for a much larger public. On the Friday-night fights, the showcase for boxing in America, Carter stalked across television screens throughout the country as the ruthless face of black militancy. He was seen as an ignoble savage, a stylized brute, an “uppity nigger.” He was out of control and, more than ever, he was a targeted man. (He was also not to be the champion. The Giardello fight, rescheduled for December in Philadelphia, went fifteen rounds; Carter lost a controversial split decision.)

After the Saturday Evening Post article appeared, authorities in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Akron, and elsewhere approached Carter when he was in town for a fight. On the grounds that he was a former convict, they demanded that he be fingerprinted and photographed for their files. At the time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s clandestine political arm, COINTELPRO (for “counter intelligence program”), was spying on Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and other civil rights leaders. Carter believed that by 1965, the FBI had begun tracking him, which simply made him more defiant.* In the summer of 1965, for example, Carter arrived in Los Angeles several weeks early for a fight against Luis Rodriguez. The city’s police chief, William Parker, soon called Carter in his motel on Olympia Boulevard and told him to get down to headquarters.

“So, you thought you were sneaking into town on me, huh?” Parker said. “But we knew you were coming, boy. The FBI had you pegged every step of the way.”

“No, I wasn’t trying to sneak into your town. I just got here a little bit early,” Carter said. A woman whom Carter had seen tailing him at the airport and his motel was standing in the office. He motioned her way, then looked back at the police chief. “My God,” he said. “She’s got a beautiful ass on her, ain’t she?”