Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

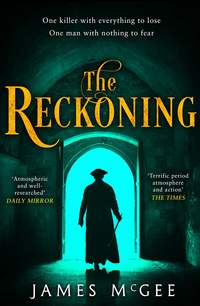

Kitabı oku: «The Reckoning», sayfa 2

“Brandy,” Hawkwood said.

Jago relayed the order to Jasper before turning back. “So, what can I do you for?”

It was such an incongruous question, coming in the aftermath of all that had ensued, that Hawkwood hesitated before answering, wondering if he’d dreamt the entire sequence of events.

“I need your help.”

Jago sat back, wincing as his injured shoulder made contact with the chair. “Jesus, you’ve got a bloody nerve. What’s it been? Three months without a word, and then you swan back in without so much as a heads-up to tell me you need a favour? Is that any way to treat your friends?”

“I just saved your life,” Hawkwood pointed out.

“Aye, well there is that, I suppose,” Jago conceded with a wry grin. “So, how was France? Heard you had a spot of bother.”

Hawkwood stared at him. “How in the hell …?”

Jago’s grin widened. “Went to see Magistrate Read, didn’t I?”

“And he told you?”

“Well, not in so many words. Would’ve been easier gettin’ blood from a stone. But seeing as I’ve helped you and him out now and again in the pursuit of your official duties, he did let slip you were abroad on the king’s business.”

“In France?”

Jago shook his head. “Guessed that bit, seeing as you speak Frog like a native and the last time I was involved you were hanging around with our privateer pal, Lasseur. Thought there might be a connection.”

Jago studied Hawkwood’s face. “Though, seeing as they ain’t declared peace and you’ve a couple more scars on your noggin, I’m guessing things might not have gone according to plan.”

Hawkwood looked back at him.

“Well?” Jago asked.

“Maybe later.”

“Which is a polite way of sayin’ I should mind my own business. All right, so how long have you been home?”

“Not long.”

“And what? This the first time you thought to drop by?”

“No. I tried to reach you a week back, but I was told you were away sorting out some business.”

Partially mollified by Hawkwood’s response, Jago eased himself into a more comfortable position and made a face. “That’s one way of puttin’ it.”

Hawkwood waited.

“A spot of bother with one of my suppliers. Had to make a visit to the coast to sort it out.”

“And did you?”

“Sort it?” Jago smiled grimly. “Oh, aye.”

Hawkwood bit back a smile of his own. In Jago’s language, “a spot of bother” could cover a multitude of sins, most of which, Hawkwood knew, stemmed from activities that were, if not strictly illegal then certainly open to interpretation when based upon the authorities’ understanding of the term. As for the remainder; they were entirely unlawful.

In the years since the two of them had returned from the Peninsula, Nathaniel Jago had made a point of steering his own unconventional career path. His experiences as a sergeant in the British Army had served him well, providing him with an understanding of both discipline and the need for organization, two factors which had proved essential in expediting his rise through the London underworld, a fraternity not known for its tolerance of transgressors, as had just been illustrated.

As a peace officer, Hawkwood had never sought to influence or curb his former sergeant’s more dubious pursuits. He owed him too much. Jago had guarded his back and saved his life more times than he could remember. That truth alone outweighed any consideration he might have for curtailing the man’s efforts to make a livelihood, even if that did tend to border on the questionable. Besides, it helped having someone on the other side of the fence to keep him abreast of what was happening in the murkier realms of the country’s sprawling capital. Providing, that is, they didn’t encroach upon a certain former army sergeant’s sphere of operations.

Not having met Del, Ned or Jasper before, Hawkwood assumed they were part of Jago’s inner circle. In the normal scheme of things, therefore, it was unlikely their paths would have crossed. Jago referring to him as Officer would have res-onated, though, so it said much for Jago’s status that none of them had raised an objection or even registered shock at his presence. That said, it was equally possible that their equanimity was due to the fact that he was alone and on their turf and at their mercy, should they decide to turn belligerent. For any law officer, the Rookery was, to all intents and purposes, foreign ground. There might as well have been a sign at the entrance to the street proclaiming Abandon hope, all ye who enter here; despite the authority his Runner’s warrant gave him, Hawkwood knew it held as much sway here as on the far side of the moon. But while he was here, he remained under Jago’s protection. Had that not been the case, his safety would not have been assured.

Unless Micah came to his aid.

Hawkwood didn’t know a lot about Jago’s lieutenant, other than the former sergeant trusted him with his life. He’d been a soldier, Jago had once let that slip, but as to where and when he’d served, Jago didn’t know, or else he knew but had decided that was Micah’s own business and therefore exempt from discussion, unless Micah chose to make it so.

He was younger than Hawkwood, probably by a decade, and, from what Hawkwood did know of him, a man of few words. There had been two occasions when, in company with Jago, Micah had stood at Hawkwood’s shoulder and both times he’d shown himself to be resourceful, calm in a crisis, and good with weapons; characteristics which had been even more evident this evening. What more was required from a right-hand man?

Jago’s voice broke into Hawkwood’s thoughts.

“All right, so what’s this all about?”

A shadow appeared at the table and Jago paused. It was Jasper, bearing the drinks, which coincided with Ned and Del’s return from their downstairs delivery.

“Good lad,” Del said, reaching for a glass. “All that totin’, I’m bloody parched.”

They might have been a couple of draymen dropping off casks of ale, Hawkwood mused, rather than drinking pals who’d just deposited three dead bodies on to a cart loaded with barrels of human waste.

Glancing around, it occurred to him that anyone walking into the room afresh wouldn’t have the slightest notion that anything untoward had taken place, save, perhaps, for noticing a few more dark stains on the floor that hadn’t been there before. Though, even as he pondered on the matter, these were being wiped away with wet rags and a fresh layer of sawdust applied.

It was uncanny, Hawkwood thought, how men and women, when surrounded by the most appalling squalor, swiftly become immune to the worst excesses of human nature. Here, where only the strongest survived, in a welter of gunfire, three men had died in as many seconds and yet, even before their bodies had been removed, the world, such as it was, had returned to normal, or as normal as it could be in a place like this.

He wondered what that said about his own actions. He was a peace officer, supposedly on the side of justice, and yet in the blink of an eye he’d knifed one man to death and shot the head off another. But then the Shaughnessys and their cohort had been prepared to murder in cold blood. Hawkwood had been a witness to that and he had acted without any thought as to the consequences. So had killing now become second nature? Was life really that cheap?

Micah reappeared.

“It’s done,” he said quietly.

Jago nodded. “That case, me an’ ’is lordship here need a bit of privacy, which means we’re commandeerin’ the table. Del, you, Ned and Jasper take a look around. See if any more Shaughnessys are loiterin’ with intent. Don’t want to be caught with our pants down again, do we?”

A pointed look towards Jasper prompted a quick emptying of glasses while three pairs of eyes swivelled in Hawkwood’s direction. Del, somewhat inevitably, was the first to speak, though his face was unexpectedly serious.

“Any friend of Nathaniel’s is a friend of ours. What you did tonight … you’ll always be welcome here …” And then the irrepressible grin returned. “… Officer.”

Jago shook his head. “God save us. All right, bugger off. I’ll see you at the Ark.”

The three men turned away.

“Oi!”

They looked back.

“You can take those with you. Don’t want ’em givin’ the place a bad name.” Jago indicated the Barbars, but then turned to Hawkwood. “Unless you want a souvenir?”

The offer was tempting. They were fine weapons; man stoppers.

“They’re all yours,” Hawkwood said.

The guns were collected and the trio headed towards the exit. Jago addressed Micah: “No more excitement tonight, all right?”

Micah nodded.

Jago winked. “Best reload, though, just in case.”

Micah’s mouth twitched. He looked off as Del, Jasper and Ned left by the back stairs and then his eyes returned to Jago and he nodded once more. Returning to his table, he took his seat, moved his discarded book to one side, and began to clean the pistol.

Jago turned to Hawkwood. “He scares me sometimes, too.”

Hawkwood took a sip of brandy, savouring the taste. He suspected it was from Jago’s private stock that the landlord kept under the counter, which meant it was French, not Spanish. He wondered if Jago’s trip to the coast had anything to do with his supply routes. Best not to enquire too deeply into that.

“Right,” Jago said. “Where were we?”

Hawkwood placed his glass on the table. “There’s been a murder.”

“In this town? There’s a novelty.”

“Any other night and I’d think it was funny, too.”

“But it ain’t?”

“Not by a long shot.”

“Which’d also be funny by itself, right?”

“Not this time,” Hawkwood said. “This one’s different.”

3

It occurred to Hawkwood, as he stared down at the body, that the last grave he’d looked into had been his own.

That had been in a forest clearing on the far side of the world. There had been snow on the ground and frost on the trees and the chilled night air had been made rank by the sour smell of a latrine ditch because that was what lye smelled like when used to render down bodies. The bodies in question should have been his and that of Major Douglas Lawrence, courtesy of an American execution detail. In the end, it had been Hawkwood and Lawrence who’d stumbled away, leaving four dead Yankee troopers in their wake and an American army in hot pursuit. It was strange how things worked out and how a vivid memory could be triggered by the sight of a corpse in a pit.

This particular pit occupied the south-west corner of St George the Martyr’s burying ground. Situated in the parish of St Pancras, the burying ground was unusual in that it was nowhere near the church to which it was dedicated. That lay a third of a mile away to the south, on the other side of Queen Square; not a huge distance but markedly inconvenient when it came to conducting funeral and burial services.

Also unique was the fact that, along its northern aspect, the graveyard shared a dividing wall with a neighbouring cemetery, that of St George’s Church, Bloomsbury, which made Hawkwood wonder, in a moment of inappropriate whimsy, if any funeral processions had inadvertently found themselves on the wrong side of the wall. There were no convenient gates linking the two burial grounds, meaning that any funeral party which turned left instead of right would have to reverse all the way back to the entrances on Grays Inn Lane and start all over again.

The burying ground’s southern perimeter was also determined by a wall, though of a greater height than the dividing one for it had been built to separate the cemetery from the grounds of the Foundling Hospital, a vast, grey building which dwarfed its surroundings like a man-o’-war towering above a fleet of rowboats. The rear of the chapel roof was just visible above the ivy-covered parapet, as were the chimneys and upper storeys of the hospital’s forbidding west wing.

The grave had been dug close to the wall, in the lee of a pointed stone obelisk, one of many memorials that had been erected among the trees. An inscription, weathered by rain and frost, was barely legible, save for the surname of the deceased – Falconer – but even those letters had begun to fade, a state which mirrored the burying ground’s general air of decay.

The overcast sky did little to enhance the wintry setting. It had been raining hard all morning and while the rain had eased to a thin, misty drizzle, leaving the grass and what remained of the winter foliage to shine and glisten; the same could not be said for the pathways and the rectangular patches of earth which showed where fresh plots had been excavated and the soil recently filled in. They had all turned to cloying mud, though, if it hadn’t been for the rain, it was doubtful the body would have been discovered.

The grave was the intended resting place of one Isaiah Ballard, a local drayman who’d had the misfortune to have been trampled to death by one of his own mules. The funeral service had been scheduled for late morning, after which the body was to be transported in dignified procession from church to burial plot, making use, somewhat ironically, of his soon-to-be equally redundant wagon.

It was a sexton’s responsibility to supervise the maintenance of the burying ground, including the digging of the graves; this particular one having been prepared the previous afternoon. The sexton, whose small stone cottage was tucked into the corner of the graveyard, had risen earlier and, in the company of two gravediggers, been making his final inspection to ensure that the interment ran smoothly.

The three men had arrived at the site to find that the mound of excavated soil by the side of the pit had been transformed into a heavy sludge. The deluge had also eaten away the edge of the grave and formed runnels in the sod down which small rivulets of rainwater were still dribbling like miniature cataracts.

On the point of directing the gravediggers to shore up the sides of the hole, the sexton’s eyes had been drawn to the bottom of the pit and a disturbance in the soil caused by the run-off. It had taken several seconds for him to realize what he was looking at. When the truth dawned, he’d raised the alarm.

When Hawkwood arrived, his first thought had been to wonder why the sexton had gone to all the bother. This was not because he viewed the examination of an unexpected dead body in a graveyard as an inconvenience, but because London’s burying grounds were notoriously overcrowded and, in the normal course of events, it wasn’t unheard of for the dead to be piled atop one another like stacks of kindling. Indeed, where the poor of the parish were concerned – to whom coffins were considered a luxury – the practice had become commonplace, which said a lot for the sexton’s integrity. It would have been easy for the gravediggers to have shovelled mud back over the body to hide it. No one would have been any the wiser.

Judging by the expression on the face of the constable standing alongside him, who’d been the first functionary called to the scene, Hawkwood wasn’t the only one harbouring reservations as to whether this was really the sort of incident that demanded the attention of a Principal Officer.

A constable’s duties rarely ventured beyond those carried out by the average nightwatchman, which in most cases involved patrolling a regular beat and discouraging the activities of petty thieves and prostitutes. So it wasn’t hard to imagine what was going through this particular constable’s mind. Uppermost, Hawkwood suspected, was likely to be the question: Why me? Followed closely by the thought: Oh, God, please not again.

The constable’s name was Hopkins. A year ago, the young recruit’s probationary period had come to an abrupt end on the night he’d accompanied Hawkwood and Nathaniel Jago in their pursuit of a crew of body-snatchers who’d turned to murder in order to top up their earnings. The chase had ended in a ferocious close-quarter gunfight. Throughout the confrontation the constable had proved brave and capable. He’d also displayed a commendable ability to look the other way when it came to interpreting how best to dispense summary justice to a gang of cold-blooded killers.

He’d filled out his uniform since Hawkwood had last seen him, though the shock of red hair was still there, poking defiantly from beneath the brim of the black felt hat, as was the pair of jug ears which would have put the handles of a milk churn to shame.

When Hawkwood arrived on the scene, the constable’s face had brightened in recognition. It was a light soon extinguished, however, for while he could be considered as still being relatively damp behind the ears, Hopkins was wise enough to know that in this situation, to smile at being greeted by name by a senior officer without the need for prompting would have been viewed as singularly inappropriate.

Squatting at the side of the trench, Hawkwood stared bleakly into its sodden depths. One good thing about the rain: it did help to dampen the smells; or at least some of them. Hawkwood didn’t know the burial practices followed in St George the Martyr’s parish. If it was like most others within the city, there would be a section reserved for poor holes: pits which were deep enough to hold up to seven tiers of burial sacks. Left open until they were filled to the brim, they allowed the stench of putrefaction to permeate the surrounding air. Nearby buildings were not immune and it wasn’t unknown for churches to be abandoned due to the smells rising from the decaying corpses stored in the crypts below them and for clergy to conduct funeral services from a comfortable distance. Hawkwood wondered if that was the reason for the burying ground’s estranged location. At the moment, the odours rising to meet him were of mud, loam, leaf mould and, curiously, fermenting apples. It could have been a lot worse.

The mud and the layer of dead leaves made it hard to distinguish details but then, gradually, as his eyes grew accustomed to the lumpy contours at the bottom of the trench he saw what had captured the sexton’s and, as a consequence, the constable’s attention. Sticking out of the ooze was the torn edge of a piece of sacking. Poking out from beneath the sacking was not a stone, as he had first thought, but the back of a human hand. Close to it was what appeared to be a scrap of folded parchment. Concentrating his gaze further, he saw that it wasn’t parchment at all, but the edge of a cheekbone which had been washed by the rain. Following the line of the bone, the ridge of an eye socket came into view.

A child, he thought, straightening. Someone had placed a child’s body in a sack and tossed it into the trench. He gazed up at the Foundling Hospital’s wall and considered the permutations offered by its proximity. He turned back to the pit. Suddenly, the sack and the shape of the contents contained within it became more pronounced. Clumps of what he had thought were clotted leaves had materialized into what were clearly thick strands of long matted hair.

A female.

He addressed the sexton. “You’re sure it’s recent?”

The sexton, whose name was Stubbs, nodded grimly. “’T’weren’t there yesterday.”

A spare, slim-built man and not that old, despite a receding hairline, the sexton was using a stick to support his left leg. The stick probably explained the gravediggers’ presence. Traditionally, the sexton was the one who more often than not did the digging.

And they would have noticed a body in a sack, Hawkwood thought. Otherwise they’d have trodden all over it.

He turned to the two gravediggers, who confirmed the sexton’s words with one sullen and one nervous nod. Their names, Hawkwood had learned, were Gulley and Dobbs. Gulley, round-shouldered with a moody cast to his features, was the older of the two. Dobbs, his apprentice, looked sixteen going on sixty. Hawkwood assumed the premature ageing was due to him having seen the contents of the trench.

Not the most promising start to a career, Hawkwood mused. Then again, it was one way of preparing the lad for what the job was likely to entail, assuming he managed to see out the rest of the day. Not that he was the only one present who’d lost colour. Constable Hopkins was looking a bit pale about the gills, too.

“Why?” Hawkwood asked.

The sexton, realizing he was the one being addressed, frowned.

“You could have got them to cover it up,” Hawkwood said. “No one would have known.”

“I’d know. Seen enough poor beggars tossed in pits without it ’appenin’ on my own bloody doorstep. It ain’t right. It ain’t bloody Christian.”

Eyeing the cane, Hawkwood took an educated guess. “What regiment?”

The sexton’s chin lifted. “Thirty-sixth.” The reply came quickly, proudly.

“You served under Burne?” Hawkwood said.

The sexton looked surprised and drew himself up further. “That I did.” He threw Hawkwood a speculative glance, as if taking in the greatcoat for the first time. Though it had a military cut, it was American, not British made. “You?”

“The ninety-fifth.”

A new understanding showed in the sexton’s eyes. He studied Hawkwood’s face and the scars that were upon it. “Then you know what it was like. You’ll have seen it, too.”

Hawkwood nodded. “I have.”

The sexton brandished his stick. “Got this at Corunna. So, like I said, seen a lot of folk die before their time.” He stared down into the trench. “That ain’t how it’s supposed to be. She didn’t deserve this.”

“No,” Hawkwood said heavily. “She didn’t.”

The sexton fell silent. Then he enquired softly, “So?”

Hawkwood studied the lay of the body and took a calming breath.

Don’t think about it; just do it.

As if reading his mind, Constable Hopkins took a tentative pace forward.

Hawkwood stopped him with a look. “Any idea what you plan to do when you’re down there?”

Hopkins flushed and shook his head. “Er, no, s—, er, Captain,” the constable amended hurriedly, clearly remembering their previous association when he’d been warned by Hawkwood not to address him as “sir”.

“Me neither. So there’s no need for us both to get our boots wet, is there? We’re officers of the law. One of us should still look presentable.” As he spoke, Hawkwood removed his coat and held it out.

Managing to look chastened and yet relieved at the same time, the constable took the garment and stepped back.

The trench was around eight feet in length and wasn’t that deep, as Hawkwood found out when he landed at the bottom and felt the surface give slightly beneath him. The height of the trench should have been the giveaway. Most graves were close to six or seven feet deep. This one was shallower than that, which meant there was, in all probability, an earlier burial in the plot. And if there was one, the chances were there had been others before that.

The burial ground had been in use for at least a century and there wasn’t much acreage. That meant a lot of bodies had been buried in an ever-diminishing space. A vision of putting his boot through a rotting coffin lid or, worse, long-fermented remains, flashed through his mind, dispelled when he reasoned that Gulley – or more likely his apprentice – wouldn’t have been able to dig the later grave as the ground wouldn’t have supported his weight while he worked. Even so, it was a precarious sensation. As it was, the mud was already pulling at his boots as if it wanted to drag him under.

Planting his feet close to the corners of the trench, still not entirely sure what he expected to find, he bent down. The smell was worse at the bottom, a lot worse. He could feel the sickly-sweet scent clogging his nostrils and reaching into the back of his throat. Trapped by the earthen walls, the smell was impossible to ignore and would have been impossible to describe. Holding his breath wasn’t a viable option. Instead, he tried not to swallow. He looked up and saw four faces staring back at him. Bowing his head and adjusting his feet for balance, he eased the edge of the sacking away from the skull and used his fingers to scrape mud from the face. As more waxen flesh came to light the gender of the corpse was confirmed.

And it was a woman, not a child.

Plastered to the face, the original hair colour was hard to determine. Lifting it away from the cold, damp flesh was like trying to remove seaweed from a stone. The smell around him was growing more rank. He tried not to think of the fluids and other substances which, over the years, must have been leaching into the soil from the surrounding graves.

Lying on her left side, mouth partly open, it was as if she were asleep. The position of the hand added to the illusion. Unsettlingly, as he brushed another strand of hair from her brow, he saw that her right eye was staring blankly back at him. It reminded Hawkwood of a fish on a slab, though fish eyes were usually brighter. Removing the mud from her face had left dark streaks, like greasy tear tracks. There was a tight look to the skin but as his fingers wiped more slime away from the exposed flesh he felt it give beneath his fingertips.

Hawkwood was familiar with the effect of death on the human body. He’d seen it often enough on battlefields and in hospital tents and mortuary rooms. There was a period, he knew, beginning shortly after life had been extinguished, during which a corpse went through a transformation. It began with the contraction of the smaller muscles, around the eyes and the mouth, before spreading through the rest of the body, into the neck and shoulders and through into the extremities. Thereafter, as the body stiffened, feet started to curl inwards and fingers formed into talons. With time, however, the stiffness left the body, returning it to a relaxed state. From the texture of the skin, Hawkwood had the feeling that latter process was already well advanced. She had been dead for a while.

Using the edge of his hand, he continued to heel the mud away gently, gradually revealing the rest of the features. The dark blotches were instantly apparent, as were the indentations in the cheekbone, which beneath the mottled skin looked misshapen and, when he ran the ends of his fingers across them, felt uneven to the touch. Tiny specks in the corners of the eye were either tiny grains of dirt or a sign that the first flies had laid their eggs.

Hawkwood let go a quiet curse. There had always been the chance that the body had been left in the grave out of desperation and the worry – probably by a relative – of not being able to afford even the most meagre of funeral expenses. Had that been the likely scenario, Hawkwood would have been willing, if there had been no visible signs of hurt, to have left the corpse in the sexton’s charge with an instruction to place the body in the most convenient poor hole. But the bruising and the obvious fracture of the facial bones prevented him from pursuing that charitable, if unethical, course of action.

He probed the earth at the back of the skull on the off-chance that a rock or a large stone had caused the damage post-mortem but, as he’d suspected, there was nothing save for more mud.

He was on the point of rising when what looked like a small twig jutting from the mud caught his eye. He paused. There was something about it that didn’t look right, but he couldn’t see what it was. Curious, angling his head for a better look, he went to pick it up. And then his hand stilled. It wasn’t a broken twig, he realized. It was the end of a knotted cord. Her wrists had been bound together.

“What is it?” the sexton enquired from above.

Hawkwood sighed and stood. “We’re going to need a cart.”

“A cart?” It was Gulley who spoke. The question was posed without enthusiasm.

“It’s a wooden box on wheels.”

Hawkwood’s response was rewarded with a venomous look. It was clear the gravedigger had been resentful of the sexton’s act of civic duty from the start. Hawkwood’s sarcasm wasn’t helping.

“You do have a cart?” Hawkwood said.

“It’s in the lean-to.” Sexton Stubbs pointed helpfully with his cane towards the cottage and the ramshackle wooden structure set off to one side of it.

“One of you, then,” Hawkwood said, pointedly.

The directive was met with a disgruntled scowl. Mouthing an oath, Gulley turned to his protégé. “All right, you ’eard.”

Looking relieved to have been delegated, the young gravedigger turned to go, anxious to put distance between him and the pit’s contents. His commitment to the job looked to be disappearing by the second.

“Leave the shovel,” Hawkwood said. “You’ll get it back.”

The apprentice hesitated then thrust the tool blade-first into the mound of dirt.

“And bring more sacking,” Hawkwood instructed. “Dry, if you have it.”

He glanced towards the sexton, who nodded and said, “There’s some on a shelf inside the door. You’ll see it.”

With a wary nod the youth about-turned and hurried off through the drizzle and the puddles.

Hawkwood addressed the older man. “You have something to say?”

The gravedigger jerked his chin at the open trench. “Don’t see why we can’t leave the bloody thing down there. We throw in some soil, we can cover it up.”

“Her,” Hawkwood snapped. “Not it. And no, we can’t. Unless you’ve a particular reason you don’t want her brought up?”

The gravedigger’s jaw flexed.

Hawkwood felt his anger rise. “Had the idea you might make a few pounds, maybe? Got an arrangement with the sack-’em-up men for the one on top? Throw in this one and you’d make a bit extra? That it?”

It could also account for the shallowness of the trench, he thought, because it made the task of exhuming the bodies that much easier.

The look on the man’s face told Hawkwood he’d struck a nerve, but he felt no satisfaction, merely increasing repugnance. Gulley wouldn’t be the first graveyard worker who earned extra spending money by passing information on upcoming funerals to the resurrection gangs, to whom freshly buried corpses were regarded as regular income, and he wouldn’t be the last. Interesting, too, that Gulley had referred to the body as the “thing”, which was what the resurrection men called their hauls.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.