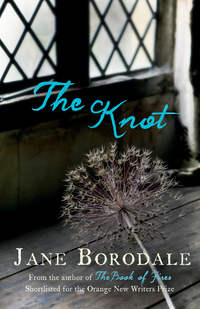

Kitabı oku: «The Knot»

JANE BORODALE

The Knot

Dedication

For my grandmothers, who both had green fingers

Epigraph

The good and vertuous Physition, whose purpose is rather the health of many, than the wealthe of himselfe, will not (I hope) mislike this my enterprise, which to this purpose specially tendeth, that even the meanest of my Countrymen, (whose skill is not so profound, that they can fetch this knowledge out of strange tongues, nor their abilitie so wealthy, as to entertaine a learned Physition) may yet in time of their necessitie have some helps in their owne, or their neighbors fields and

gardens at home.

henry lyte, A Niewe Herball

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

THE FIRST PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

THE SECOND PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

Chapter XV.

Chapter XVI.

Chapter XVII.

Chapter XVIII.

THE THIRD PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

Chapter XV.

Chapter XVI.

Chapter XVII.

THE FOURTH PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

THE FIFTH PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

Chapter XIV.

Chapter XV.

THE SIXTH PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

Chapter VIII.

Chapter IX.

Chapter X.

Chapter XI.

Chapter XII.

Chapter XIII.

THE SEVENTH PART

Chapter I.

Chapter II.

Chapter III.

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

Chapter VI.

Chapter VII.

THE EIGHTH PART

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Also by Jane Borodale

Copyright

About the Publisher

THE FIRST PART

The Place

1565

Chapter I.

Of BORAGE. Which endureth the winter like to the common Buglosse. The stalke is rough and rude, of the height of a foote and halfe, parting it selfe at the top into divers small branches, bearing faire and pleasant flowers in fashion like starres of colour blewe or Azure and sometimes white.

TWO HOURS OF DIGGING, and Henry Lyte still feels that unrecognizable discomfort.

Like a slight tipping, washing inside him, a darkish fluid lapping at his inner edges as though in a dusk, yet when he turns to it; nothing, nothing. Perhaps he is about to be unwell. Perhaps the Rhenish wine last night at supper was old or tainted, or he had too much of it.

A man of nearly thirty-six with all his health should not be troubled by sudden, unspecifiable maladies. Being at work on the garden out in the fresh air should be enough of a wholesome antidote to sitting hunched and bookish in his study, over his new, impossible manuscript that is going so slowly. There is satisfaction to be had from being outside instead, slicing and turning the light brown, clayish soil, breaking it into the kind of finer ground he needs for planting. The day has been good for October, bursts of rain giving way to bright sunshine, yet still it is not enough to distract Henry Lyte from being so ill at ease. He decides that as he can’t place the sensation, nor what provoked it, he will try to ignore whatever it is. Probably nerves, he thinks. It is not every day that a man is due to ride up to London to collect his new wife. His second wife, and they have been married for three months already, but she has not been to Lytes Cary yet. Within the week her postponed marital life and duties with Henry are to begin. He leans on his spade and considers the hulk of the manor house, the sky to the north dark behind, and wonders what she will make of it.

Lytes Cary Manor is made of limestone, a modest huddle of yellow gables and chimneys embedded comfortably on a mild slope of arable land where the Polden hills begin to rise up out of the damp flatness of the floodplain that is the Somerset Levels. The estate itself spreads down onto the damp moor in several places, but most of it sits on higher ground over a knoll in the crook of a bend in the river Cary, as far as Broadmead and Sowey’s Fields, then out onto the lower, uncertain ground of Carey Moor. Lytes Cary stands on the very brink of the Levels, and in winter these marshy acres to the south-west are inundated with shallow salty water from the sea and can be traversed only by boat. The Mendip hills are high and blue in the distance to the north, to the far south-west are the Quantocks, and to the near west, at about seven leagues off lies Bridgwater Bay, with its bustling port and the wide murky sea that stretches to Wales.

About the house sit diverse barns, the malthouse and dovehouse, and tenants’ cottages, many put up in his father’s time. Henry can still remember improvements being made to the house when he was a boy. The adjacent manor of Tuck’s Cary is almost uninhabited, just a handful of tenants, since Henry’s brother Bartholomew died of a pleurisy four years ago. There is also a hop yard, two windmills and several withy beds.

The new garden project here, however, is of his own devising.

To his knowledge, this part of the grounds has not been cultivated for at least two generations, though it lies alongside the kitchen garden that feeds the household, and the little plot in which his first wife Anys grew a few of the most vital herbs. Sheep have been folded here right up by the house on this grass during summers for years, so the soil has been kept fertile with dung, and it is level, south-facing, and as well-drained as any of this clay country is likely to be. Now the earth needs to be prepared and opened up, so that the frosts can penetrate the clods and break it down over the winter months.

He likes digging. He likes the pull of the spade against the earth, the tilting strain on his back, the mud drying on his palms. More accustomed to directing men than taking up the tools himself, he is always surprised at how much you can be changed by working physically till you ache. The world seems more vivid, more manageable. He does not feel it is at all beneath him as a man of status to be at work like this, instead he imagines his guardian spirit glancing down approvingly from time to time, saying, look, see how he takes charge of his affairs, because that is how it feels to be digging into the good soil with the iron spade and mattock.

And then of course he remembers that guardian angels are no longer the stock in trade of any churchman worth his salt, nor any true believer, and are resorted to only by those such as his cook, Old Hannah, still cutting her surreptitious cross into the raw soft dough of every loaf on baking day. At thirty-six, Henry Lyte does not practise his faith in the way he was instructed as a boy, nor as a youth, because the world is not now as it was, not at all. It has changed, and changed again.

While he digs he is free to let his mind wander, and he dreams his kingdom of pear trees in the orchards across to his left, growing skywards, gnarling, putting forth fat green soft fruits with ease each year. The trees that already grow in the orchards he loves almost as women in his life; the Catherine pear, the Chesil or pear Nouglas, the great Kentish pear, the Ruddick, the Red Garnet, the Norwich, the Windsor, the little green pear ripe at Kingsdon Feast; all thriving where they were planted in his father’s ground at Lytes Cary before the management of the estate became his own responsibility as the eldest son. So much has happened these six years since his father handed over and left for his house in Sherborne: there have been births and deaths – Anys herself was taken from him only last year. But the pear trees live on, reliably flowering and yielding variable quantities as an annual crop that defines the estate, and he has plans to add more.

He wonders – as he does at some point without fail each day that passes – whether it would have been better if his father had, despite everything, attended his wedding to Frances. Three months have passed now since the ceremony, and the fact of his father’s deliberate, calculated absence on that day is a smouldering hole in their relationship, there is no doubt. Henry had stood with his bride-to-be at the church door perspiring with anxiety and the heat of July, in the hope that his father would appear as invited, despite Henry’s letters having met with a deafening silence. After almost an hour the chaplain could wait no longer, as he had others to marry at two o’clock, so he garbled through the litany and vows, and the thing was done without his father being there. Henry would have liked his approbation, but there was nothing to be done about it, for his father, when he gets an idea into his head, is a stubborn man.

That in itself was an inauspicious start, and then suddenly Frances was burdened with pressing, unexpected matters to attend to in London because by great misfortune her own, beloved father had died on their wedding night. Her mother had needed assistance with probate, which proved a terrible family tangle that Henry was unable to involve himself with. After several weeks he had returned to Lytes Cary alone to deal with his own estate that could not, after all, run itself, and sent up diffident, occasional letters to his new wife as though to a stranger. Now her brother has come to the aid of their mother so that Frances’s presence is no longer essential, and tomorrow at last he goes up to London to fetch her.

Henry digs on to the end of the row, straightens up and looks south, and finds now that evening is already creeping up the hill from the west, that the large, yellowing sun is close to the horizon. A green woodpecker flies to a branch of the tallest willow at the end of the bank and squats back belligerently on its tail, the slope of its red cap bright in the grey of the tree. Henry always calls that bird the Sorcerer, it has a menacing, ethereal presence he would rather do without. From there the bird has a commanding view of its surroundings, it knows more than he does about their mutual territory.

The sweet savour of dug earth is all about, and yet for a moment Henry Lyte thinks he can smell the sea – a weedy, salt smell of unwanted water. Then it is gone – perhaps it was a draught of air drawn over the half-completed brick wall from the heap of rotting compost in the kitchen garden, some stalks of greens maybe, or kale. But Henry Lyte pauses, and for a moment has a strong thought of the sea itself wash round his head – the great blank sea that lies in sheets of water against the low shoulder of the land at Berrow, the wide strip of coast where the mouth of the river Parrett coils its way out across the mud flats at low tide below the dunes thirty miles from here.

It must be explained that the sea there is held back by only the thinnest strip of land at high tide, and with the highest tides in winter the sea wall is often breached. But these winter floods are to be expected; they are planned for, understood by farmers, eel fishermen, migrating birds. Unseasonal deluge has never happened in his lifetime; that would be more of a threat to human life than he would care to think of. Nevertheless, it is said that a true native from these parts, with marsh-blood going back centuries, is always born with webbed feet, because nothing can be taken for granted in this precarious world. Unusual weather stems from unusual circumstances. It certainly felt that way just after the death of Anys, the winter that followed – last winter – was the coldest and deepest he could ever remember. And there are plenty who believe that bad weather is a punishment from God.

Downwind of the chimney, Henry can smell what might be supper and the unaccustomed exercise has made him hungry. He props his tools in the outhouse and bolts it tight, goes into the house by the back door. His blisters sting satisfyingly as he washes his hands in the ewery. The dog in the porch beats her tail without raising her head, a young mastiff bitch called Blackie who has developed a reciprocal loyalty to this half of the house rather than to her master. He puts his head in the door to his left. The kitchen at Lytes Cary is high and cavernous, the rack over the broad fireplace hung with hams and sides of salted beef and bacon, gigots of dried mutton, stockfish, ropes of onions and long bundles of herbs. On the east wall is the great oven, and ranging off to the west are the pantries and buttery and dairyroom, and all of this is Old Hannah’s dominium, filled tonight with meaty steam and the fatty goodness of something fried. Three blackened cauldrons sit at the hearth, beside a stack of gleaming earthenware and a basket of scraps for the poor as it is Tuesday tomorrow. One vast wet ladle lies across the mouth of a brown pot, and a row of pewter plates laid out indicates that serving is imminent. He won’t disturb her; if she gets talking things might go cold. Old Hannah has a rolling walk, it is always alarming to watch her crossing the kitchen carrying a large pudding basin filled brimful, or a cleaver for chopping the heads off plucked fowls. Tom Coin who works in the kitchen with her is a gangly sprout of a boy with a long, earnest face and hair of the soft brown sort that grows very slowly. Through the door in the cross passage Henry can see that Tom has set the trenchers in the hall, cut up the maslin bread, lugged in the pitchers of the small beer that is suitable for hindservants, and is just about to call supper for the household.

Tonight though Henry thinks he will eat with the children separately in the oriel. A speech that a father must have with his girls before the arrival of their new mother – God knows but he never thought he’d ever have to say such words to them – must be done in private. As he walks through the hall the armorial glass in the windows above to his right glows with the setting sun outside, casting a ruby-coloured light of the ancestors over the swept floor and the plain trestles. There is no escaping the ancestors, and they observe – as God does, but with perhaps more vested interest – his every movement through this place.

Chapter II.

Of BISTORTE. They grow wel in moist and watery places, as in medowes, and darke shadowy woods. The decoction of the leaves is very good against all sores, and it fastneth loose teeth, if it be often used or holden in the mouth.

IT IS LATE, BUT HENRY LYTE can never sleep easily on the eve of a long journey. He sits with the trimmed candle burning low and ploughs on with his translation. He is an orderly man who likes to work in a state of neatness, which should stand him in good stead for the task ahead of him. There is, after all, a place for brilliance of mind and there is a place for method, and he feels he may have enough of the latter to complete all six hundred pages. He has ink of different colours ranged in pots on his desk; red, black, purple, green and brown, for different types of fact or notes, and he likes a sharp nib. Surrounded by other men’s herbals for ease of cross-reference, he is working directly from the French version as L’Histoire des plantes, which is itself translated out of the Flemish by Charles l’Écluse, or Carolus Clusius, as the great man prefers to be known. He hasn’t decided what his own is going to be called. A title is crucial and difficult to decide upon, he’s finding. The original work, startlingly detailed and scholarly, was published in 1554 as the Cruÿdeboeck by the learned Rembert Dodeons, a master of plants and medicine, whom Henry himself had met when he was in Europe as a young man all those years ago. Sometimes Henry blushes with embarrassment to think that he has been so audacious as to consider himself man enough for this enormous undertaking. Why him? Not a physician, not an expert in anything. It is almost ridiculous, but the project is well underway now, too late to turn back.

He has finished butterbur and begun bistort today, which is a familiar kind of herb to him. Some plants are easier to render quickly because it is very clear from their descriptions or the Latin what their equivalents might be in English. Others are not, and he will have to return to those later, get specialist opinion, exercise extreme caution and assiduousness in applying names to them. The excellent plates by Leonhard Fuchs are also of considerable help in identification, but grappling with the French is his own charge entirely. He hovers over a disputable word. What is ridée in English? He thinks. He notes down rinkeled, folden, playted or drawn together. He considers his sentence, and then writes the great bistort hath long leaves like Patience, but wrinkled or drawen into rimples, of a swart green colour.

He can hear from the creak of boards upstairs when Lisbet leaves the children’s room and goes off to where she sleeps in the chamber over the dairy in the north range. With her departure all four children settle down in their beds and a quietness conducive to writing subsides throughout the house. For two full hours Henry works hard enough to forget most of what weighs on his conscience, though it is a temporary displacement. When the second candle is burnt about halfway down its length, he retires to bed to dream of nothing.

Chapter III.

Of PAULES BETONY. The male is a small herb, and créepeth by the ground. The leafe is something long, and somwhat gréene, a little hairy, and dented or snipt round the edges like a sawe.

HIS NEW WIFE FRANCES, daughter of the late John Tiptoft, London, distant cousin to the Earls of Worcester, is standing for the first time at Lytes Cary in the hall. It is a wet blustery autumn day. The highways from London these past six days have been very bad for mud and their passage was slow, beset with driving rain and herds of animals on their way to market; broken branches and at least one diversion to avoid hazardous bridges. Henry loathes driving in a carriage as it is painfully cumbersome, and makes a man’s limbs sore and stiff, doing nothing on a lumpy, jolting road for such a distance, but Frances had refused to ride on horseback so far in weather like this. They might have been better hiring a horse litter for Frances, with Henry riding alongside, as even with allowances made for the sluggish nature of progress by carriage, the journey had taken a day longer than it should as a wheel was lost and they had to put up overnight at the inn in Stockbridge whilst the axle was repaired at the wright’s. But now here they are. This feels momentous, her arrival here; perhaps more so than the marriage itself. There is baggage due to follow when her mother comes next month.

Four o’clock in the afternoon, and the fire has been lit with all speed to honour her entrance and take the chill off the hall. Someone has swept out the leaves and dirt that sift into the porch on windy days and has left the besom propped in the passage. All of the household is gathered here to glimpse the new mistress; John Parsons his bailiff; Old Hannah, Lisbet and other servants; the dairymaid; Richard Oxendon the horseman; various farmhands, and several tenants’ children clustered at the door. Frances removes her chaperon and cloak, goes straight to the hearth and stands shivering against the yellow fire. Her black hair is in rats’ tails from being blown about. She says nothing at all. Old Hannah mutters something to someone Henry cannot see. Henry tries to be jolly, stands beside her feeling stiff and damp and out of sorts and makes an awkward joke about the countryside, whilst all the time trying to recall how she’d looked when he saw her last. She seems very different here. Her skin is unnaturally white and smooth. He has a strong impulse to touch her cheek to see if there is any warmth to be had from it. She is like a doll, a figurine. He had wanted, expected her to look about and take in her new surroundings eagerly. She had been so pleased to see him, so chatty for much of the journey, pointing out distant spires of churches and asking questions. She must be feeling the very great difference of what she is now, he thinks, and is occupied with that. She is anxious, perhaps, or very tired. Yes of course, she needs hot food to eat and then her bed should be warmed. It must be that she is white with exhaustion, quite blanched through with it, indeed he can see now that she is almost swaying on her feet. Henry Lyte feels guilty that he hadn’t thought of that more promptly. She looks ready to faint.

‘Lisbet!’ he claps the servant over to take his wife to her chamber. A boy is dispatched to the carriage to bring in her first of many bags and cases.

‘Send up a caudle,’ he tells the cook. ‘Or a dish of eggs. Something hot and quick. My wife is tired.’ He is annoyed with himself for not having sent word on ahead to have a spread of food prepared ready for her arrival. Clearly he is out of the habit of being married to someone younger. The crowded hall filters away to usual duties, until it is very quiet in here, just the spit and crackle of the freshly lit fire.

His girls, all stood beside it in a row, are watching him like little owls. Edith, at twelve years old the eldest, opens her mouth to speak but then closes it again. He looks at her, and then at Jane, who is nine, with baby Florence on her hip. At Mary, six, then back to Jane again – and is baffled.

‘What?’ he says.

His new wife is asleep in the very middle of their bed by the time he goes up to see how she is, a plate of half-eaten tart and an empty mug on the floorboards at the end of the bed. He parts the curtains and holds up the candle but she does not stir in the pool of light. Her face is fine-boned and angular. Her breathing is deep and even, she lies with the cover pulled up over her chemise and one narrow wrist flung out. It seems bad-mannered to climb in and push her across, so he takes a blanket from the wicker coffer and retires for the night to the dressing room, where he does not sleep because the owls are so loud on the roof above him.

In the morning he goes to his study to give his wife time to get ready in their chamber before coming down. He is not going to be a stranger in his own house ordinarily, but this is, after all, the first day: the first day of his new life. He stands at the window that gives onto the garden and watches a fine rain coming down and the green Sorcerer out on the grass, up-loping toward the ants. He sees Tom Coin coming back from the fishponds with a large carp flapping so much he can hardly keep it in the basket. Henry opens the window and leans out, and the noise of chopping up in the coppice tells him that the woodman is not idle, despite the weather. There is nothing seemingly wrong at all, and he should be glad for it. Why then does he feel so angry? It makes no sense. The Sorcerer puts his thick head up and seems to laugh at him as it flies away towards the wood.

‘I had no choice but to marry, I have four surviving daughters to consider. Four, dammit! They cannot run free in the mud like dottrill or little urchins. They need a woman’s hand to oversee their maturation, to bring them up in a civilized way until they are of age and can enter the world as wives and then mothers. They need to know French, totting-up, how to stitch, how to make sweet malt, bind a man’s wound, how to be in charge of the kitchen. Not everything can be taught by a nurserymaid.’ He indicates out of the window at the rainy scene. The grass is sodden and deserted, though to the far left a cow is being driven into the yard from Inner Close for milking.

‘Look at it out there,’ he demands, to the empty room, ‘what civilizing influences will be had by them if I do not seek it?’

He regrets that there has been no time for grieving – practical matters to attend to when a family member dies seemed on this occasion to take all his vigour for months afterwards, he has felt blank and sucked dry of any melancholy or other emotion. He does not mean he didn’t suffer pain but that he felt it like a physical blow to the body, so that he sat by the hearth alone at night aching as though he’d been in a fight. Yes, it was just that he’d been in a fist-fight with death on behalf of his wife and had lost. It is all perfectly normal. Doesn’t everyone suffer deaths within their close family circle?

In the year that his own mother Edith died, coffins went up the road to the church almost every week. There had been fair warning that death was to be afoot that year – in March around Lady Day there had come a great comet, reddish like Mars, half the size of the moon in diameter, with a flaming, agitated tail that stretched itself across the night sky and scorched a rightful terror into the hearts of those who looked upon it. There were many who said it was a clear token from God that the end of Catholic rule was near, and that Queen Mary’s tumour may have begun with its manifestation. A comet is a sure sign of change, or death. He hopes never to see another body like it in the sky. His mother had died in exceptional pain, drenched in sweat and gasping for air in what had been the hottest summer for eleven years, as she clung to his hand for those last dreadful days. Sometimes across his knuckles he feels the grip of her bones still, has to flex all his fingers to free himself of it. And sometimes when his eye catches at the horizon just after sunset, the first bright sight of Venus makes his blood pound momentarily, mistakenly. It is surely unthinkable that another comet of that stature could appear twice in a man’s lifetime.

His father, remarried himself after Edith’s passing within two years, has no right to listen to any bad claims against his character. It’s just the usual way of things, to marry again.

‘Everybody does it,’ Henry goes on aloud to no-one. ‘Hadn’t I waited a decent length of time since Anys was taken from us by the will of God? By God’s will alone. It had been nearly a year.’ With this last thought, a draught blows under the door, and for a second he almost thinks he can catch the scent of her brushing against him like a substance.

Anys smelt of leather polish and warm skin and oats. She smelt of hard work and prayerbooks and children and bread. He is sure he has remembered that right. He is sure she knew how well she was esteemed by him. He swallows. The whole business is unavoidable. He leaves the study hastily, goes to the last of his new wife’s boxes stacked in the hall, and carries them up.

He had lost two servants soon after the funeral, but they’d each had good reasons, as they explained, for their change of situation. Lisbet is the new maidservant, she replaced Sarah who was a diligent worker. He had let her go with regret, Anys had thought so well of her. Lisbet is tolerably good, but he did wish he couldn’t hear her feet slopping down the corridor all the time when he is trying to concentrate. Why does she never pick them up when she walks? It occurs briefly to Henry Lyte that her shoes might not fit properly. She has a pleasant enough face. There is even something quite appealing about the crooked tooth that juts out a little over her lip, though it is the kind of countenance that will not age well, and of course he knew her mother. He prefers to hire local girls like her, they stay for longer, ask fewer questions, and he doesn’t think she can have heard anything of what happened. The misunderstanding will all simmer down and be forgotten. He hopes that Frances herself will never hear what people have said of him. It is just a matter of time. People forget so easily; memories are flimsy, friable things that get buried and mulch down into the past like vegetation. A few will stick, of course, inevitably. His memory of what happened is already concentrated to a few sparse images that he cannot shake off. One can be forgiven for forgetting a detail here or there – even though details, the little unimportant daily things amassed together over time, are what makes up most of living. What does his own life add up to, he suddenly wonders. In forty years, a hundred years, three hundred, what will be left of him?

He recalls a distinct, disturbing sensation he had once in his early days as a student a long time ago, in one of Oxford’s many bathing houses. It was not the sort of place that he was to frequent very often, but he was a young man missing home, missing his mother, and had gone for comfort, a little bit of human warmth that could be bought straightforwardly with sixpence.

A pretty doxy by the name of Martha was rubbing at his back with oil, plying her knuckles to his spine, to the very bones inside his muscles, and smoothing backwards and forwards across his shoulders in a shape like a figure of eight, her breathing ragged with exertion. There was a good savour of flowers or resin all around. Afterwards she was friendly to him, and didn’t seem to mind that he had fallen asleep.

‘How was that?’ she’d asked, prodding him gently and pouring a drink from the jug. He’d thought carefully, yawned and sat up. He examined the back of his hands, turned them over as if seeing them for the first time.