Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

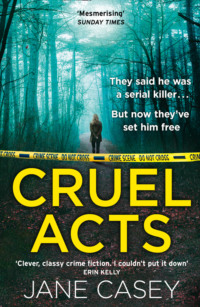

Kitabı oku: «Cruel Acts», sayfa 2

‘Kerrigan.’

‘It was an accident,’ I said quickly.

He gave me the kind of look that he usually reserved for child-killers at the very least, and for a beat I held my breath. Then he lifted the box out of my hands as if it weighed nothing and walked away.

‘I can manage,’ I said to his retreating back, futilely.

‘Thank you, Maeve,’ Una Burt said from behind her desk, and I remembered where I was, and left her to her discussions with Godley and the pathologist.

4

Derwent was always a fast mover. By the time I made it out of Una Burt’s office, he was already on the other side of the room, well out of reach. He set the box down beside Pettifer’s desk with a remark that made the big DS throw his head back and laugh. I started towards them – it was still my case to hand over, I thought with a shiver of irritation – and checked myself as Georgia stepped into my path. She had found a hairbrush and cleaned herself up a bit. She’d managed to find the time to reapply her mascara, I noted.

‘What was that about?’ She nodded towards the office behind me. ‘Is that Superintendent Godley?’

‘Yeah.’ Of course Georgia would have spotted him. She had an extraordinary instinct for career advancement.

‘What’s he doing here?’

‘He had a job for me.’

‘Can I help?’

I raised my eyebrows. ‘You don’t even know what it is.’

‘So?’ Georgia’s blue eyes were unblinking. I could see it from her point of view: a chance to impress the boss before he came back to the team. Get a head start. Make progress.

‘I’m not in charge of this one.’

‘Who is? DI Derwent?’ She swung round, looking for him.

‘You’re going to be working with Pettifer on the Clarke case,’ I said firmly. ‘Once that’s out of the way, we might be able to use you. But at the moment—’

She pulled a face, obviously annoyed. ‘Pettifer can finish the Clarke case on his own.’

‘He could, but he isn’t going to.’ I stared her down for a long moment, daring her to take it further, and in the end she broke first.

‘So what’s the case?’

‘Reinvestigating—’ I broke off to cough. ‘Reinvestigating the Leo Stone case.’

‘The White Knight? Wow. I would love to work on that.’

‘Noted.’ There was nothing to encourage her in my tone of voice.

‘Why did Superintendent Godley want you to work on it?’ Her eyes were narrow.

Derwent leaned in between us. ‘Because he has a soft spot for Kerrigan.’ Georgia laughed.

‘Because he thinks I’ll do a good job,’ I said stiffly.

‘Of course you will.’ Derwent patted my arm.

Instead of arguing the point I walked away from both of them to talk to Pettifer myself. Georgia could try to convince Derwent to let her work on it too. If he wanted her, he’d include her in spite of my objections. If he didn’t want her help, nothing I could say would persuade him. Either way, I didn’t need to hang around.

He caught up with me in the kitchen where I was waiting for the kettle to boil.

‘What’s up with you?’

‘Nothing.’ I coughed again. Shit, I didn’t want to be ill. ‘I’m tired. I’m cold. I want to go home.’

‘My home.’

‘I’m renting it. That means it’s my home. Temporarily, anyway.’ I still wasn’t used to living in a space that I associated so completely with Derwent. For instance, I’d discovered there was no bleach strong enough to take away the mental image of him lounging in the bath.

‘As long as you’re looking after it.’

‘Yeah, I don’t want to piss off the landlord.’

‘Oh, you’ve done that already. Look at me.’

I did, reluctantly. He was holding the sides of his jacket open so I could see the muddy mark that ran across his chest. Not just the shirt: the tie too. ‘I said I was sorry.’

‘No, you said it was an accident.’

‘Well, it was.’ I took a deep breath. ‘But I’m sorry.’

‘Finally. You’re forgetting your manners.’

‘Speaking of which, I could manage the box by myself. You didn’t even ask before you took it.’

His eyebrows went up. ‘Don’t try to pretend that’s why you’re in a mood.’

‘I’m not in a mood.’ I turned and leaned against the kitchen counter, gripping it for courage. ‘I am very annoyed that you decided to stir up trouble by hinting that Godley wanted me to work on this case for any other reason than that he thinks I’m a good detective. You of all people know how unfair it is to suggest he puts professional opportunities my way for personal reasons.’

Derwent gave me his stoniest look. ‘That’s not what I did.’

‘Isn’t it?’

‘No.’

‘Saying he had a soft spot for me?’

‘It’s banter.’

‘It needs to stop. It’s not a joke. Someone like Georgia who doesn’t know any better will take it seriously, and I’ve had enough of it. You know it’s not true and you know there are a lot of people who’d like to believe that it is.’

‘You can’t live your life worrying about what other people think.’

‘Spoken like someone who doesn’t ever have to worry about it.’

‘You don’t have to. That’s my point. You’re choosing to care.’ He shrugged. ‘These people aren’t worth getting upset about. If they want to think the worst of you, they will, whether I say anything or not.’

‘Maybe, but you don’t have to throw fuel on the fire.’ Frustration was a knot in my stomach. It was impossible to explain how I felt to Derwent, and he didn’t have the imagination to put himself in my shoes. The gulf between his life and mine was unbridgeable. ‘You have no idea what it’s like to have to prove yourself over and over again,’ I said at last.

He rolled his eyes. ‘I have a fair idea.’

‘Because I’ve told you before. And yet, here we are, having the same conversation all over again.’ I turned away from him and squashed the teabag against the side of the mug, viciously. When I flicked the teabag at the bin I had the very small satisfaction that it went in first try.

‘I’ll keep it in mind,’ Derwent said at last. He almost sounded sincere. He would never admit he had been wrong, though, and nor would he apologise.

‘Thanks for being so understanding.’ I poured the milk into my tea and watched little white specks bob to the surface. ‘Oh, for fuck’s sake, who puts gone-off milk back in the fridge?’

‘Poor Kerrigan. It’s not your day,’ Derwent said, and left, whistling as he went.

I leaned against the wall, defeated. I was tired and cold and fed up. All I’d wanted was a hot bath, a good meal and an early night. Instead I had nothing to look forward to but a long evening on my own, reading about someone else’s investigation and some very dead women. Not my day, not my week, not my year.

5

I had read the files and looked at the photographs until my eyes burned; I had watched the CCTV that the first investigation had painstakingly located and analysed. I knew the circumstances of Sara Grey’s disappearance inside out. Still, as Derwent drove down the Westway, I felt my pulse getting faster. Sara Grey. Victim one, chronologically.

‘Bloemfontein Road is coming up on the left. Not this one, the one after.’

Derwent slowed to make the turn.

‘This was where the tyre gave up.’

‘Puncture?’

I nodded. ‘They never worked out where she picked up the nail. There was nothing forensically interesting about it. Probably bad luck rather than Leo Stone’s planning. We have CCTV of her here, turning into Bloemfontein Road.’

‘Tell me about her.’

‘Sara Grey was twenty-nine at the time of her disappearance. She was engaged to Tom Mitchell, who was the same age as her. She was a primary school teacher; he had his own property development company.’

‘Did they ever check to see if he had employed Leo Stone?’

‘I didn’t see anything about it in the files.’ I scrawled a note to myself to look into it. ‘He was in Latvia on a stag weekend when it happened. Otherwise he’d have been suspect number one.’

‘Being out of the country doesn’t let him off the hook as far as I’m concerned. It’s a bit too convenient.’

‘Poor guy. If he’d been in the UK you’d be even more convinced he was involved.’

‘It’s always the husband. Or the fiancé. Or the boyfriend. Or the ex.’

‘Not this time. The original investigation focused on Tom, though, before her disappearance was linked to the others. They were looking for money worries or secret affairs or any kind of motive. They didn’t find anything.’

Derwent grunted, not convinced.

I leafed through my notes. ‘There was nothing to say Sara was being stalked – no concerns for her safety, no threats. On the day she disappeared no one was following her – at least as far as the investigators could determine.’

Derwent had slowed down to a crawl, creeping down Bloemfontein Road. ‘So what happened then?’

‘She parked just where that Volvo is. It was eleven at night but it was a Saturday, a summer night. There was a lot of traffic on the main road and there were people around. It was a warm evening – there’d been thunderstorms earlier but it was clearing up. When she got out of her car, she was seven hundred and eighty yards away from her home at 37 Haddaway Road.’

Today the light was flat, the clouds brooding over our heads. It was hard to imagine the street wrapped in the dark heat of a humid summer night.

Derwent pulled in a few cars ahead of the Volvo and parked. ‘Then what?’

‘Then she sent a text message to her fiancé telling him what had happened.’ I flipped to the relevant page and read it out. ‘Flat tyre!!! I don’t know what to do.’

‘The poor bloke was in Latvia. How was he supposed to come to the rescue?’

‘She probably just wanted to tell someone what had happened.’

‘No, she wanted to make him feel guilty for being off on a stag weekend instead of here.’

I raised my eyebrows at him. ‘That’s a very jaundiced view, even for you.’

‘She was high maintenance. I have limited patience for that.’

Melissa, Derwent’s girlfriend, was not the sort of person who would be low maintenance. If it had been anyone else I might have said as much, but Derwent had made it clear time and time again that while my personal life was endlessly entertaining, his was not available for discussion. Beside me, Derwent drummed his fingers on the steering wheel, as if he knew what I was thinking. ‘Then what happened?’

‘He replied: “Oh shit. Where r u? How bad is it? Driveable?” Obviously it wasn’t. She checked their AA membership and discovered it had lapsed so she decided to walk home. She sent him a message to that effect at 23.15.’ I showed Derwent the relevant page.

I can’t drive it. Left the car on Bloem Rd and I’m walking home. You can sort it out when you get back tomorrow.  <3 <3

<3 <3

Derwent grimaced. ‘Something for him to look forward to.’

‘He replied, “Typical! Call me when you get in.”’ I flipped the page. ‘According to this, “No further calls were made or received from Miss Grey’s phone and no further messages were sent by her. Mr Mitchell did not hear from his fiancée again after the message sent at 23.14. Cell site analysis revealed the phone remained switched on for a further twenty minutes, at which point it was powered down. Mr Mitchell informed police that it was highly unusual for Miss Grey to turn her phone off.”’

Derwent peered out of the car. ‘It looks like a safe enough area.’

‘It is. And they’d lived here for a year. She knew exactly where she was and she knew the quickest way home was going to be on foot.’

‘She should have been safe here.’ After a moment, he focused on me again. ‘So what route did she take?’

‘We don’t know.’ I pulled out a map I’d printed off. ‘This is Haddaway Road where she was heading. The direct route is along this road here, Haigh Road, leading into Radcliffe Road.’

‘Any reason to think she didn’t go that way?’

‘A bit of her mobile phone handset was found on Radcliffe Road in a hedge.’

‘OK. Sounds promising.’

I flattened the map out and pointed to a star I’d drawn. ‘It was here. Quite a long way from the path. I wonder if it was thrown out of a moving vehicle.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘This sighting of a couple arguing.’ I leafed through the file and pulled out the witness statement. ‘The witness was a Mrs Hamilton. She lives on Cordray Road, here.’ I showed him where it was on the map. ‘She was driving home and happened to glance along a side street in this area – she couldn’t be specific about which street it was but it was somewhere off Simpson Road.’

Simpson Road was about a quarter of a mile south of Haigh Road. ‘That’s way off the route she should have been taking,’ Derwent said.

‘Exactly. It was around the right time though. The investigators spent a lot of time trying to get Mrs Hamilton to remember anything else but she wasn’t a great witness, reading between the lines. She got more and more confused and in the end she said she couldn’t be sure of anything she’d told them. She withdrew her statement.’

Derwent groaned. ‘Good work, lads.’

‘It was a dark night, she was driving, she glanced down a side street and sort of saw two people who might have been arguing. It wasn’t going to make or break the case even if she remembered every detail.’

‘What did she say about the man?’

‘Nothing. He was standing behind a white van. She didn’t see more than the back of his head.’

‘Leo Stone’s pretty distinctive. He’s tall, for one thing. She’d have noticed that, surely.’

‘She said not. All she could say was that he was taller than the woman.’

‘How tall was Sara Grey?’

‘Five two.’

‘Right, so my nan would be taller than her.’

‘Yeah. It wasn’t altogether helpful testimony. Wrong place, right time, few details.’ I tapped my pen on the map. ‘The van, though.’

‘I like the van.’

‘We all like the van. It’s one of the only points of comparison we’ve got, apart from where the body ended up and how it was left, and that’s Dr Hanshaw’s territory.’ I didn’t need to say the rest because Derwent knew as well as I did that if that was called into question, we could lose Sara Grey altogether. The pathologist’s evidence was a big part of what had put Leo Stone behind bars. Without it, he could walk for good.

Derwent opened his door. ‘Let’s follow her route. Work out the timings. What time did Mrs Hamilton see the arguing couple?’

‘Half past eleven.’

‘So how long did she have to get there?’

‘Fifteen minutes or so.’

He looked me up and down. ‘Your legs are about twice as long as Sara Grey’s. You’ll have to take baby steps.’

Even with Derwent slowing me down (‘Oi, giraffe, put the brakes on’) it was possible to walk as far as Simpson Road in fifteen minutes. The area was middle-class, quiet, the houses well kept. It had been two and a half years since Sara Grey disappeared and there was no point in looking for evidence but I imagined her walking home, moving fast, her head down, and I wondered how she could have ended up so far off course. For once, Derwent was thinking the same as me.

‘Why would you go this way?’ He pulled the map out of my hand and studied it, frowning. ‘If we assume Mrs H was right about what she saw.’

‘These are busier roads than the direct route. Maybe she wanted to stay where there were more people around. Alternatively, something was making her uneasy. If someone was following her, she might have taken a different route home, trying to shake them off.’

‘Wouldn’t she have wanted to go straight home? Get indoors where she was safe?’

‘Not if she was concerned about them knowing where she lived. She’d never feel safe again if she led them to her door, even if she made it inside without coming to grief.’

Derwent shook his head and walked away.

‘What?’

‘Just …’ He swung back to face me. ‘What a way to live, that’s all. Working out what risks to take. Who to trust. Walking fifteen minutes out of your way to give yourself a better chance of making it home in one piece.’

‘That’s life, isn’t it? What’s the alternative? Staying at home?’

‘Maybe.’

‘You’re not serious.’ I folded my arms. ‘If anyone should stay at home, it’s men. They’re the ones who cause most of the trouble.’

‘Like that’s going to happen.’

‘Well, women shouldn’t have to hide away either.’

‘It’s for your own good.’

‘You have to live,’ I said quietly. ‘You look over your shoulder. You check who else is in your train carriage. It’s second nature – like looking both ways when you cross the road.’

‘I don’t always look both ways.’

‘I know.’ I had hauled him back onto the pavement out of harm’s way more than once. ‘I can’t decide if it’s male privilege in action or reckless stupidity.’

‘Bit of both.’

I started walking back towards the car. ‘Let’s assume for a minute that Leo is our killer. What was he doing here? He doesn’t seem to have any connection with the area. He didn’t grow up here. He never lived here. So why go hunting here?’

‘Good point.’ Derwent looked around. ‘This is the sort of area you’d only visit if you had a reason to. What are we close to? Westfield?’

We weren’t too far from the giant shopping centre that was one of the main attractions of west London. ‘I don’t know if Stone is a big shopper. Hammersmith Hospital is the other side of the Westway. And so is HMP Wormwood Scrubs.’

‘Did he ever do time there?’

‘I don’t know. I’ll check. And I’ll check if he visited anyone there.’

‘You think he didn’t act alone?’

‘It’s one possibility,’ I said. ‘At the moment, I don’t feel as if I know anything about him.’

‘Maybe he followed her off the Westway. If he saw the flat tyre he’d have known she was in trouble. Offer to help – Bob’s your uncle.’

‘They checked the CCTV and didn’t see it. The only person who saw a van was Mrs Hamilton.’

‘And she didn’t get the VRN.’

‘What do you think?’

Derwent sighed. ‘All this time in the job and I’ve never had a single witness with a photographic memory.’

‘Me neither.’

‘They must exist.’

‘They’re too busy passing exams and winning pub quizzes to be witnesses.’ I thought for a second. ‘He had the van. Where was he working when this murder took place?’

‘You should find out.’

‘I should, and I will.’

Derwent stopped beside the car and stretched. ‘So this is the last place anyone saw her alive. When did they find her body?’

‘A long time later. She disappeared on the twelfth of July 2014, and her body was found in December. And the only reason it was discovered was because Willa Howard’s body was dumped in the same nature reserve. A visitor to the reserve found Willa, and then DCI Whitlock’s team searched the rest of the area. They were the ones who located Sara’s remains. That’s when it became clear that Leo Stone was responsible for Sara’s death as well as Willa’s.’

His forehead crinkled as he considered it. ‘Even though there’s basically nothing in the way of physical evidence or eyewitness testimony.’

‘Leo has always sworn blind he had nothing to do with Sara Grey’s disappearance.’

‘He would.’

‘He convinced her parents he was innocent.’

Derwent shook his head. ‘Then they’re as gullible as their daughter was.’

6

‘So, three months on from Sara Grey’s disappearance, he’s on the hunt again. And he finds Willa Howard slap bang in the middle of Bloomsbury.’

‘Before that, there was Rachel Healy.’

Derwent frowned. ‘He was never charged with her murder.’

‘Because they never found the body.’

‘Is that the only reason?’

‘Not entirely,’ I said. ‘When they searched Stone’s house they found blood under the floorboards, but it was degraded. They couldn’t get a full DNA profile, but what they found didn’t match Willa Howard or Sara Grey. They checked it against the DNA of missing women from the greater London area over a five-year period and the most similar one was Rachel Healy. She disappeared three weeks before Willa Howard and hasn’t been seen since.’

‘And the blood was the only thing that connected her with Stone?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Let’s stick with Willa and Sara for now, since he was charged with their murders.’

‘What about Rachel?’ I had read about her last of all, the previous night when I was yawning and desperate for sleep; it hadn’t taken long and it had woken me right up. Of all of Stone’s possible victims, she had received the least attention. No body, no evidence, no leads. A dead end.

‘If we have time, we can talk about her. But there are probably good reasons why they left her out of the original case. Three weeks before Willa Howard doesn’t leave much of an interval. Sara Grey was three months before that.’

‘It’s not scientific. They don’t mark murder opportunities on their calendars,’ I snapped.

‘That’s not what the profilers say.’

‘And you have so much time for what profilers say.’

He grinned at me. ‘It’s science. They’re basically infallible.’

I rolled my eyes, knowing full well that he thought the opposite of what he was saying. ‘Look, what are the chances the blood doesn’t belong to her? She fits the profile of the other victims, and the way she disappeared—’

‘Noted,’ Derwent said, in a way that meant I don’t care. ‘Back to Willa.’

‘Willa is the reason they found Stone in the first place. Say what you want about the original investigation but DCI Whitlock did a good job with Willa. She went missing on the thirty-first of October – Halloween. The last time anyone saw her was in the Haldane, a pub about five minutes’ walk from here.’

We were parked in Corona Mews, a narrow cobblestoned lane with three-storey mews houses on either side. Some of the buildings were businesses, the shutters pulled back on the ground-floor spaces that the private homes used as garages. It was an expensive little enclave, despite its faintly bohemian air, and it was quiet. This was the secret hinterland of Bloomsbury, part of a warren of close-set streets that were invisible from the busy thoroughfares that bordered the area, funnelling traffic north to King’s Cross and south to Holborn.

‘So what are we doing here?’

‘Willa’s disappearance was out of character – she didn’t turn up at a family event the following day, her phone was off, she’d just broken up with her boyfriend. The local CID started looking for her straight away. She hadn’t used her Oyster card on any of the local buses or the underground and they didn’t pick her up on CCTV. She was very striking – she was tall, with long fair hair that she wore loose, and she had been distressed when she left the Haldane because of the argument she’d had with her boyfriend. It was Halloween. There were lots of people wandering around, but no one remembered seeing her.’

Derwent was listening intently. ‘He must have picked her up near the pub.’

‘That was the theory. They canvassed the area, looking for anything unusual, and they found Miss Middleton.’

‘Who is Miss Middleton?’

‘She is the resident of number 32, Corona Mews, and she does not like visitors.’

On cue the front door of number 32 opened and a narrow face appeared. ‘You can’t park there.’

Derwent slid down his window. ‘Police.’

‘Am I supposed to be impressed?’ She made little shooing motions. ‘Go on. Hop it. This isn’t a car park.’

‘Miss Middleton?’ I leaned across so she could see me. ‘We wanted to talk to you about Willa Howard.’

‘What, again?’ She was a foxy little woman with wiry dyed-red hair and sharp brown eyes. I guessed she was eighty but she was spry with it. ‘I thought I was done with all of that.’

‘Not yet, I’m afraid.’

Derwent got out of the car and she stared up at him, hostility warming into something more like appreciation. ‘Well.’

‘May we come in? I promise to wipe my feet.’

‘You’d better.’ She gave a short cackle. ‘Got to put me face on, since I’ve got visitors. Make your own way up.’

For a pensioner, she had a fine turn of speed, and by the time I shut my door she had disappeared.

‘I know I’m going to regret this,’ Derwent said.

‘Once we’re finished here we can go to the pub.’

‘But we’re on duty.’

‘I’ll buy you a lemonade.’ I peered up the stairs. ‘Can’t keep a lady waiting, sir. You’d better go first.’

Viv Middleton was waiting for us in her sitting room, enthroned on a reclining armchair that faced an enormous flat-screen television. She had applied dark lipstick with more speed than accuracy. The place was spotlessly clean and sparsely furnished – a sideboard, a small cupboard, a single upright chair to one side of the recliner with a library book on it. It looked as if it had been decorated last in the early 1980s. Two big windows overlooked the street and from the recliner, Viv would have had a perfect view.

‘You can take the chair if you want,’ she said to Derwent. I got, ‘You’ll have to stand.’

‘Don’t worry,’ Derwent said, adopting his usual pose with his feet planted far apart. ‘I’ve been in the car all day. I need to stretch my legs.’

‘Ooh, well don’t let me stop you.’ She cackled happily. For once, Derwent looked embarrassed. He folded his arms and stared at the floor.

‘Miss Middleton, you were a key witness. What can you tell us about the van you saw?’ I asked.

‘It was parked outside my house for two weeks, on and off. He’d come early in the morning and go late at night. Too quick for me, even though I was watching for him. I left notes on it, you know. Telling him he couldn’t leave the van there. And I made a note of the registration number. Complained to the council a few times but they’re useless.’

‘So you never saw the driver,’ I checked.

‘Not Stone. No. I saw him in court. Horrible-looking man. Give me the shivers. You could see he was a killer.’

‘Did you see anyone else near the van? Or driving it?’

She shook her head. ‘I only ever saw him driving away. I’d hear the door go and look down but he parked the wrong way for me to see who was driving. He’d get here early in the morning and I don’t do mornings.’

‘What was he doing here? Was there any building work going on in the street?’ I asked.

‘There’s always someone doing building work. Listen to that.’ She held up a hand and I heard the distant whine of an electric drill.

‘And none of your neighbours saw him?’

She snorted. ‘They don’t notice anything. Half of them are rented out – what’s it called – holiday stays type of thing. The other half are too far up themselves to notice a van unless it’s blocking their Ferrari or Jaguar.’ She dragged out the syllables of the car names, rolling her eyes for comic effect.

‘Not like you,’ Derwent said. ‘How come you live here?’

‘I spent sixty years working for a lovely man, an American. I was his housekeeper. He was rich as you like but he didn’t get on with his family because he was gay, you see, and they couldn’t accept that. He left me this place for the rest of my life. His family want to get me out but there’s nothing they can do. I’ll be carried out of here.’ She grinned, showing off false teeth as white and regular as piano keys. ‘All I need is someone to look after me now. What is it they call them?’

‘A carer?’ Derwent suggested.

‘No, that’s not it.’ The grin widened. ‘A toy boy, that’s the one.’

Miss Middleton gave us special permission to leave our car parked in front of her house while we walked down the narrow cobbled streets to the Haldane pub.

‘How did they link the van to Leo Stone?’ Derwent asked.

‘The registered owner was traced to a Travellers’ site in Hertfordshire. He said he’d sold it to a man he knew as Lee. Lee had promised to register it as his, but he hadn’t completed the paperwork. He didn’t know where Lee lived but he had a mobile phone number for him.’

‘Lee being Leo?’

‘Lee being Leo. They found him in Dagenham, in a house that belonged to his aunt – she died a few years ago and left it to him.’

He’d been watching television and drinking cheap lager at eleven in the morning, almost four weeks after the disappearance of Willa Howard.

‘When they searched the house they found a room with a new hasp and padlock. He said there was no key and they never found the key in the house or garden, but when they cut the padlock off they found this.’ I handed Derwent a spiral-bound album of photographs and he flicked through it: the front of the small, post-war house – three windows and a door, like something drawn by a child. The hall, a narrow and dim space with old-fashioned wallpaper. A dirty kitchen. An untidy sitting room, the surfaces covered in dented cans and takeaway containers. A pile of clothes in the corner of the room. A blanket thrown over the end of the sofa. The door behind the sofa. The padlock. The room behind it: a cheap bedframe with broken slats fanning out underneath it. A new mattress on the bed, still covered in protective plastic. No furniture, except for a large steel storage cupboard in the corner of the room. Derwent paused.

‘And this is significant, I take it.’

‘Turned out to be. It was second-hand, bought through a local buying-and-selling group and collected from outside the seller’s home while they were at work. The buyer paid cash. It was designed to contain hazardous materials. It even had an integral sump in case of any spillages.’

‘Useful.’

‘Very.’

It was empty, the inside spotless except for a wisp of plastic.

‘They didn’t work out exactly where the plastic came from but it’s the type decorators use for protective sheeting when they’re painting a room. There’s no record of Leo buying anything like that but he was in and out of building sites. He could have nicked it.’

The next picture was a close-up of the plastic. Derwent pointed at a smudge. ‘Is that blood?’

‘A tiny amount of it, and it belonged to Willa Howard.’

‘Well, there you go.’ Derwent snapped the book shut and gave it back to me. ‘That’s him done and dusted.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.