Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

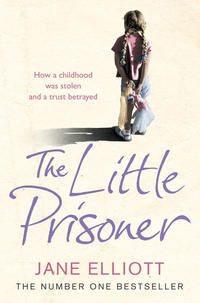

Kitabı oku: «The Little Prisoner: How a childhood was stolen and a trust betrayed»

The Little Prisoner

How A Childhood Was Stolen and A Trust Betrayed

Jane Elliott

with Andrew Crofts

Evil is unspectacular and always human, and shares our bed and eats at our table.

W. H. Auden

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

A Note from the Author

Prologue

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Epilogue

Make www.thorsonselement.com your online sanctuary

Copyright

About the Publisher

A Note from the Author

As a child I never thought anyone would believe what I had to say, so when my book went straight to number one in the hardback bestseller charts and everyone was talking about how brave I was to tell my story, I found it hard to take in. One minute I would be hugging myself with excitement, and the next I would be frightened of what might happen now I’d let the genie out of the bottle.

Initially I wanted to write the book because I knew how much I’d been helped by reading A Child Called It by Dave Pelzer. If just one child who was being abused read my story, I reasoned, and felt inspired enough to speak out and end the cycle of bullying in their own life, it would be worth doing.

Every time my publishers rang to say they were printing more copies to meet the demand, I imagined how many more people would be reading it and maybe seeing that it was possible for them to turn on the bullies and regain control of their lives.

The actual writing process was hard because it stirred up one or two memories and emotions that I’d been trying to forget about. But now I’ve shouted out to the whole world all the things I was told had to be kept secret, it feels as though a lead weight has been lifted off my shoulders.

However hard I’d been trying to suppress the memories over the years, they were always there. I could distract myself with family chores, a bottle of wine or a packet of cigarettes, but that didn’t make the hurt go away for more than a few hours. Facing up to the memories and telling the whole story was like opening the curtains and windows on a sunny day and letting light and a fresh breeze into a dark room, stale with poisonous air.

One of my biggest worries was how my children would react to the book. They’re both still young and although they knew that something bad had happened in my childhood they didn’t know any details. I’ve told them the book contains material they might find upsetting and that I would rather they didn’t read it until they were older, and so far they’ve managed to resist the temptation – I think. The excitement of hearing their mum talking on the radio and seeing the book all over the shelves in the supermarket and W H Smith seems to have more than compensated them for any worries it might have caused them.

The hard thing for them is that they’re not allowed to tell their friends about it. This was particularly tough when it was at the top of the charts and they were longing to share the excitement that was going on within our little family group. But they’re all too aware of the dangers of disclosing my true identity and of my whereabouts being discovered by my family. They saw what happened to their mum last time her brothers caught up with her, and they don’t want to take the risk of that happening again. They keep telling me how proud of me they are. I just hope they realize how proud I am of them as well.

My husband has also had to adjust from being the sole worker in the family to having to stay home a lot to look after the girls while I was off at publishers’ meetings and giving interviews, but there have been some big compensations for him too. The sense of satisfaction I got from seeing how well the book was doing made me a lot easier to live with (not that I’m not still a bit of a nightmare for him some days!), and we have been able to pay off a few of the debts we were building up and improve our lives materially.

I don’t think he really believed the book would be a great success any more than I did, but it’s surprising how quickly we both got used to having a number one hit and started to feel disappointed when it got knocked down to number two or three!

The charts are full of stories of childhood abuse now and there have been a lot of articles in the press speculating on why so many people want to read about such a difficult subject. I don’t think it is the abuse they want to hear about, but the fact that some of the children who suffer from it manage to survive and ultimately triumph. They want to be shocked at the start of the book, crying in the middle and exultant at the end.

I suspect that the audiences for books like The Little Prisoner fall into two categories. Firstly there are those who come from stable, happy homes, who can’t understand how anyone can abuse a child, and want to find out about a world they can barely imagine. Secondly, there are those who suffered something similar themselves and find some comfort in discovering they are not alone in the world. They get some inspiration from discovering that not only is it possible to go on to lead happy and normal lives, but that you can actually turn all that misery into something positive.

I have a horrible feeling there are more people in the second category than anyone really wants to admit, and as long as the subject remains shrouded in secrecy and is considered a taboo to talk about, we’ll never know the full extent of the problem. With the popularity of books like mine, however, at least we have started to open the curtains and let a little light into these darkest and nastiest of corners.

If we don’t all understand what is going on in families like the one I came from, we can’t hope to make things better.

Prologue

When people talk about evil they are usually thinking of mass murderers like the fictional Hannibal Lecter or dictators like Adolf Hitler, but for most of us our actual encounters with evil are more mundane. There are the school playground bullies and sadistic teachers who turn their victims’ days into nightmares, the unkind care workers in the old people’s homes or the violent thieves who invade the lives of the elderly or infirm. Our brushes with these evils are usually passing or secondhand, but none the less chilling for that.

This, however, is the true story of a four-year-old girl who fell into the power of a man for whom evil was a relentless daily activity. She remained in his power for seventeen years until she eventually managed to escape and turn the tables. It is a story of terror and abuse on a scale that is almost unbelievable, but it also tells of her enormous act of courage which led to the arrest, trial and imprisonment of her persecutor.

Most of us don’t usually hear about children like Jane until we read about their deaths in the papers and then we all wonder how such things could be going on under our noses and under the noses of all the welfare workers who are supposed to be there to help. We try to imagine what can have gone wrong, but we can’t because these children live in a world that is unimaginable to anyone who hasn’t been there. This is the story of a survivor and we should all listen to what she has to tell us.

Jane Elliott’s story is almost unbearable to read in parts, but it needs to be told because the people who perpetrate these sorts of crimes rely on the silence of their victims. If people talk openly about what happens behind closed doors, then evil on the scale of what happened to Jane becomes harder to achieve. Bullies can only operate when other people are too frightened, ashamed or embarrassed to talk about what is being done to them. By telling her story, Jane is making it a little harder for evil to prosper in future.

The names of the characters have all been changed to protect Jane’s identity and the identities of those who helped her in her fight for justice.

Introduction

I was being led back into the courtroom by a victim liaison officer, an elderly lady. Up till then they had been careful to take me in and out of a different door from Richard, my stepfather, or if they hadn’t then they had made sure we didn’t meet, which was making me feel more confident. Hiding behind my hair, I had still been able to avoid seeing him and remembering his face too clearly. As I came back in through the door with my head down I saw a pair of shoes directly ahead of me, blocking my way. I looked up, straight into a face that made me feel sick with fear. The pale snakelike eyes and the ginger hair were the same, although he looked a little stockier than I remembered him.

‘Get me out of here,’ I hissed through gritted teeth, feeling his eyes boring into mine and his thoughts getting back inside my head. ‘Get me out, get me out.’

‘Calm down, for heaven’s sake,’ the lady said, irritated by such a show of emotion. ‘Come through here.’

She led me into a room off the court, which had a glass door. He followed us, but didn’t come in, standing outside the glass, just staring at me with no expression.

‘Get the police!’ I screamed. ‘Get the police!’

‘Don’t be silly, dear.’ She was losing patience now. ‘Who is it you’re worried about? Is it him?’ She gestured towards the immobile figure on the other side of the glass with the dead, staring eyes.

‘Get someone!’ I screamed and she realized there was no way she could calm me down. She walked towards the door. ‘Don’t leave me!’ I screamed, suddenly envisaging him and me in the room alone. The woman was panicking now, aware that she didn’t know how to handle the situation.

At that moment Marie and another police officer arrived. Finding me standing in the corner of the room, hiding my face against the wall like a child in trouble, they came to the rescue, furious with everyone and getting me to safety.

‘He’s going to kill me,’ I moaned as Marie put her arm round me. ‘I’m dead.’

‘No, he won’t, Jane,’ she soothed me. ‘He can’t do anything now. You’re doing fine. It’s nearly over.’

Chapter One

Early childhood memories don’t always remain in the right order or come back the moment they’re called, preferring to remain stubbornly locked in secret compartments deep in the filing cabinets of my mind. Sometimes I can picture a scene clearly from as young as three or four, but I can’t remember why I was there or what happened next. Every now and then the lost memories will return unexpectedly and often it would have been better if they’d remained lost. I have a horrible feeling that there are still some compartments for which my subconscious has deliberately lost the key, fearing that I won’t be able to cope with what would come out, but which one day will allow themselves to be forced open like others before them. It is as if they wait until they know I will be strong enough to cope with whatever is revealed. I don’t look forward to seeing what’s inside them.

I can’t always piece together the order that things happened in either. I might be able to remember that I was a certain size at the time that some event occurred, but be unable to tell if I was four or six. I might be able to remember something that was a regular occurrence, but be unable to say whether it went on for a year or three years, whether it was every week or every month. I suppose it doesn’t matter very much, but this confusion makes it difficult to give a truly factual account of the early years of my life, since anyone else who might be able to remember those times will probably have reasons not to tell the truth, or at least to adjust it to make their role in it more bearable.

I do remember being in care with my little brother Jimmy. I must have been about three when we were taken away from home and he would have been about eighteen months younger, so still little more than a baby. I loved Jimmy more than anything in the world. My dad tells me that when he used to come and take us out of the children’s home for a pub lunch or some such outing, I would act like a little mother to Jimmy, feeding him and fussing over him. I don’t recall the outings, but I do recall how much I adored Jimmy.

The main things I remember about the children’s home were the brown vitamin tablets they used to dispense to us each morning in little purple cups, and being made to eat Brussels sprouts and hating every damp mouthful as they gradually grew colder and more inedible on my plate.

There was one woman working there who used to single me out from the evening line-up, after we had all been given our glasses of milk, and take me somewhere private, putting her finger to her lips as if we had a secret from the rest of the world. Then she would sit me down and comb my long hair, spending ages curling it and making me feel beautiful and special for a few minutes each day. (My hair was so dark and fine that people were always asking me if I was Indian or Pakistani.) When she’d finished her work the woman would give me a hand mirror to hold up in front of me so I could see the back of my head in the mirror on the wall and admire her handiwork. It seemed like a magic mirror to me.

Most of the information I picked up later about those early years and why we were taken away from home came to me because Mum was always happy to talk about me to other people as if I wasn’t there. I’d be sitting quietly in the corner of the room, waiting for an instruction as to my next duty, while she would be holding forth to some neighbour or other. Every so often she would remember I was there and remind me, ‘Don’t you ever let him know I told you that.’ My stepfather didn’t like anyone to talk about the past.

When I was in my mid-twenties I tracked Dad down and he’s told me a few things, but I don’t like to keep asking him questions. It seems that Dad had a bit of a drinking problem, which Mum made worse by playing around with other blokes and generally giving him a hard time. He had already left us before we were taken into care and Mum had started going out with Richard, or ‘Silly Git’, as I prefer to think of him. He might even have been living with us by then, although he would have been very young, no more than sixteen or seventeen. He’s only fourteen years older than me.

Jimmy and I were sent to a couple of different foster homes, one of which I think must have been quite nice, since I can’t remember much about it. The second one wasn’t so good. They seemed like evil people to me, but perhaps they were just very strict in a way I wasn’t used to. We were never allowed to whisper to each other, or speak unless we were spoken to, and when they caught me whispering to Jimmy one time they stuck a piece of tape over my mouth which had been holding together a pair of newly bought socks. I had to sit at the top of the stairs with the tape over my mouth all night while everyone else in the house went to bed.

Even though I wasn’t having a good time in the foster family, I still never wanted to go back home, but I wouldn’t have been able to explain to anyone why not.

‘I’m really looking forward to coming home,’ I would tell Mum when I saw her, but I absolutely wasn’t.

When we went back home for visits there was an atmosphere in the house that made me frightened, although nothing bad actually happened in those few hours. I would sit very quietly, not wanting to make the new man of the house angry, but Jimmy had no such inhibitions and from the moment we were dropped off he would scream with what sounded like terror. I could tell it made Richard angry and that frightened me even more, but nothing I could do would calm Jimmy down until the social workers came to take us back. We would just sit together on the sofa for the whole visit with him screaming and me trying to comfort him. Richard’s anger and our mother’s desperation would swell to what felt like dangerous proportions as they waited for the ordeal of the visit to be over.

Jimmy had a large scar right around his forehead, which has stayed with him into adulthood. I was always told that he got it from falling against the coffee table before we were taken into care. I accepted the story at the time, but thinking back now, it’s an awfully big scar to get from bumping into a table. He was only tiny, so it wasn’t as if he had far to fall, or much weight behind him. I wonder now if something more serious happened to him and that was why we were taken into care and why he was always so terrified to go back home. I don’t suppose I’ll ever know now because Jimmy was too little to remember.

Someone told me that we were taken into care because we were being generally neglected, that we had vivid, sore ‘potty rings’ from where we had been left too long on our pots, but everyone seems to be vague about the details.

Before we went into care we’d lived in a flat, but by the time my memories start to kick in Mum and Richard had moved to a council house. Maybe that was how they managed to convince the authorities that they were fit to have me back. They’d also had a baby boy of their own, called Pete, which must have made them look like a more normal family, like people who had mended their ways, matured and accepted their responsibilities. Richard was, after all, still a teenager, but there might have been a case for believing that he had now grown up enough to be put in charge of children.

I sometimes wonder whether Mum and Richard would have taken me back if I’d made as much fuss as Jimmy. Now I wish I’d given it a go, since Jimmy ended up being adopted by kind people, but at the time it seemed too dangerous to make Richard angry and I preferred to remain docile and well-behaved in his presence.

Years later I discovered that they had told the authorities they ‘only wanted the girl’. I couldn’t believe it, but Jimmy’s files later confirmed it. Jimmy had read the files himself and felt deeply rejected, even when I assured him that he’d had the luckiest escape of his life.

I also heard Mum boasting that our family had slipped a bribe to someone in the local authority to allow me home and that two senior people had resigned when they heard that I was being returned to ‘that hell-hole’, as it was described in some report. My missing files would make interesting reading, but it isn’t really important what happened in those first few years, because the real horrors were only just about to begin.

One of the scenes that has always remained clear in my head was saying goodbye to Jimmy on the doorstep of the foster home. He was crying and I wanted to as well, but didn’t dare to show my feelings to anyone. Someone had told me that Jimmy would be coming back home as well in a couple of weeks, but I didn’t believe it. I think I must have overheard something that told me they were lying. I knew they were going to separate us and it broke my heart. I’d hated it at the foster home, but at least I’d had Jimmy with me. Now I was going to be moved to somewhere else where I felt bad things would be happening and I wouldn’t even have him to cuddle and talk to.

I still didn’t tell Mum any of these thoughts; I just told her that I couldn’t wait to get home. I didn’t want to hurt her feelings. Little children only want to please their parents if they can.

From the moment Jimmy and I were parted I used to try to communicate with him telepathically whenever I was on my own. I had a birthmark on my arm which I convinced myself looked like the letter ‘J’, so I would stare at it and try to talk to Jimmy in my mind, telling him to be a good boy and assuring him that I would come to see him soon, asking him what sort of day he had had and telling him all about mine. I never did see him again until we had both grown up and grown apart, but at the time it comforted me a little to think I was still connected to him.

After Pete, Mum and Richard had three more boys, one almost every year, but none of them could take Jimmy’s place in my heart. I had to keep this quiet because I was never allowed to talk about him again. It was as if he had never existed in our lives. We had a lot of secrets like that. I was never allowed to tell anyone that Richard was my stepfather, not my real father, although anyone living in the neighbourhood must have known. My four half-brothers never realized that I wasn’t their full sister until I was in my late twenties and the court case brought everything to light. I was never allowed to have any contact with any of my relations on my father’s side; it was as if they didn’t exist. I have no memory of my grandparents on that side at all. It was as if Richard wanted to keep control of exactly what information was allowed.

My dad tells me that he tried to come and visit me in the house a few times, but was met with such violence and abuse that he decided it would be safer for me if he stayed away and allowed things to calm down. That seemed like the last of my potential allies gone, although I later discovered he had tried to keep an eye on what was happening to me in other ways.

One day a photograph of Jimmy fell out from behind another picture in an album.

‘Who’s that? Who’s that? Who’s that?’ one of my little brothers asked.

Richard immediately became angry, throwing the picture in the bin and making it clear that there were to be no more questions about the little boy in the photograph. Jimmy was no longer part of our family.

Any house we lived in inevitably became a gleaming domestic fortress. I guess that another reason why Mum and Richard were able to convince the authorities that they would be good parents to me now was that they kept their home spotlessly clean and totally secure. My stepfather was obsessed with decorating; there was never a day when he wasn’t redoing one room or another with new flock wallpaper, the sort you see inside old fashioned pubs, or applying another coat of paint, or putting up pine cladding or building fake brick fireplaces. I even used to cover my schoolbooks in the offcuts from old rolls of his flock wallpaper.

Our privacy was everything to him. Net curtains covered the windows during the day and would be reinforced by expensive thick lined velvet curtains as soon as the light outside started to fade. God knows where they got the money to buy them, but they ordered them from catalogues. There could never be a chink left in our armour, anything that would allow prying eyes the slightest opportunity to see inside our private lives. Outside the houses would be gates, high fences and even higher conifers. Locks and bolts would ensure that no one, not even members of the family, could get in and out easily. Richard’s control over his domain was total. Our houses were always the ‘nicest’ in the area.

All of us did housework all the time. Not a speck of dust or dirt ever escaped Richard’s eagle eye. If a bit of fluff came off one of our socks onto the carpet we were immediately screamed at to pick it up, so we would pad around in slippers to be on the safe side. Visitors could never believe that anyone could keep a house with children in so clean and tidy. Every kitchen cupboard would have to be emptied and wiped down every day, every item of furniture moved and cleaned and replaced, even the cooker and the fridge. Ledges above doors and windows that would normally be out of sight and out of mind were wiped down every single day. We sparkled and shone like an army barracks ruled over by a sergeant major prone to terrifying rages. The stairs had to be brushed by hand each morning and Mum would then vacuum them three or four times more during the course of the day.

The garden received just as much attention, the edges of the lawn having to be trimmed with scissors.

But doing housework was a way of keeping busy and out of Richard’s way in case he was in one of his moods.

Richard was about four years younger than Mum and only eighteen when I was taken back home, but to me he was still a fully grown adult and I knew that to answer him back or disobey him in any way would be to endanger all our safety. Children know these things instinctively, just as they know which teachers they can play up at school and which ones will never tolerate any bad behaviour. Even though I’d hated being made to take tablets at the children’s home, I’d never been frightened to fight back against the staff administering them, but something about this man told me that if I fought back or protested in any way, things would become a thousand times worse.

He didn’t look like a monster, although he was over six feet tall, slim and muscular. He had ginger hair and pale snakelike eyes and always dressed casually but smartly. He took great care of his appearance, just like his home. I ironed his clothes so often over the years I can remember exactly what he owned: the neatly pressed pairs of jeans and polo shirts, the v-necked jumpers and Farrahs trousers. When I got older my friends sometimes used to tell me they fancied him, which made me want to be sick because to me he seemed the ugliest thing in the world. He had a tattoo of Mum’s name on his neck to show the world how tough he was.

The moment I was swallowed up into the house and invisible to the outside world, he made his hatred of me plain. Every time he passed me when Mum wasn’t looking he’d slap me, pinch me, kick me or pull my hair so hard I thought it would come out at the roots. He would lean his lips close to my ears and hiss how much he loathed me while his fingers squeezed my face painfully like a vice.

‘I hate you, you little Paki bastard,’ he would spit. ‘Everything was good here until you came back, you little cunt! You are so fucking ugly. You wait till later.’

His hatred for me seemed to be so powerful he could hardly control himself. To call me a ‘Paki’ was the worst insult he could think of, since he carried his racist views proudly, like badges of honour.

He took to spitting in my food whenever he had the opportunity and I would have to mix the spittle into the mash or the gravy to make it possible to swallow, since he would force me to eat every last scrap.

‘You ain’t leaving the table until you’ve eaten every mouthful,’ he’d say, as if he was merely a concerned parent worrying about his child’s diet, but all the time he would be grinning because he knew what he had done.

When my brother Pete was old enough to talk he saw it happen one time.

‘Er, Dad,’ he screeched, ‘why did you spit in Janey’s food?’

‘Don’t be stupid,’ he snapped. ‘I didn’t.’

When I saw that Mum’s attention had been caught, thinking I had a witness in little Pete, I found enough courage to say, ‘Yes, he did. He always does.’ But she couldn’t believe anyone would do such a disgusting thing and so from then on Richard was able to turn it into a double-bluff, making loud hawking noises over my plate and then dropping even larger globs of phlegm into it when my mother looked away, tutting irritably and telling him ‘not to be so stupid’, as if it was no more than a joke that she no longer found funny.

I think she must have known how much he hated me, though, because she never seemed to like to leave me alone in a room with him for any length of time when I was tiny. If she could see he was in a mood and she had to go to the toilet, she would call me to come with her, a bit like calling a dog to heel. When we got inside she would make me sit down in front of her with my back to her knees while she did her business. I can’t think of any other reason why she would have done that, but we never spoke about it and I was always happy to go with her, knowing that it was saving me from a slap or a kick. What she never realized, however, was that Richard didn’t have to be in a mood to hit me or punch me or hiss insults into my ear – he did it all the time.

The house had three bedrooms, so I had a room of my own from the start and it was beautifully decorated, just as a little girl’s bedroom should be. To begin with my wallpaper was ‘Sarah Jane’ with pictures of a little girl in a big floppy hat, then it was changed for a Pierrot design, and later a pattern of horses. I had loads of toys, too, but I was never allowed to play with them unless I did Richard some ‘favour’ in return.

These favours became my way of life. If Mum let me go out to play while Richard was out somewhere and he came home and found me outside, then I would ‘owe him a favour’. If I wanted to eat a sweet or go to a friend’s birthday party or watch The Muppet Show, he might say yes, but would let me know that I would be paying him back with a favour later. In the end I stopped asking for anything, but he would still demand the favours or call them ‘punishments’ for some ‘crime’ instead, like being rude or sulky. Looking back now I realize that he was going to make me do the favours anyway, so I wish I had got more in exchange for them, but I wasn’t able to see so clearly what was happening at the time. He managed to make it all so confusing and frightening. My favourite toy was Wolfie, a giant teddy with a dog’s head, which was almost as big as me. Wolfie had braces which I used to slip my arms through so he would dance with me and walk around the room. He was my best friend.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.