Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

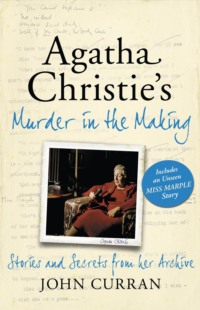

Kitabı oku: «Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Making: Stories and Secrets from Her Archive - includes an unseen Miss Marple Story», sayfa 2

1

Rule of Three

‘One of the pleasures in writing detective stories is that there are so many types to choose from: the light-hearted thriller … the intricate detective story … and what I can only describe as the detective story that has a kind of passion behind it …’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

The A.B.C. Murders • After the Funeral • Appointment with Death • The Body in the Library • Curtain • Death in the Clouds • Death on the Nile • Evil under the Sun • Endless Night • Hercule Poirot’s Christmas • The Hollow • Lord Edgware Dies • The Man in the Brown Suit; • ‘The Man in the Mist’ • ‘The Market Basing Mystery’ • The Mousetrap • The Murder at the Vicarage • ‘Murder in the Mews’ • The Murder of Roger Ackroyd • Murder on the Orient Express • The Mysterious Affair at Styles • One, Two, Buckle my Shoe • Ordeal by Innocence • A Pocket Full of Rye • Sparkling Cyanide • Taken at the Flood • They Came to Baghdad • They Do It with Mirrors • Three Act Tragedy • ‘The Unbreakable Alibi’ • ‘Witness for the Prosecution’

‘Surely you won’t let Agatha Christie fool you again. That would be “again” – wouldn’t it?’ Thus read the advertisement, at the back of many of her early Crime Club books, for the latest titles from the Queen of Crime. The first in the series to appear, bearing the now-famous hooded gunman logo, was Philip MacDonald’s The Noose in May 1930; Agatha Christie’s first Crime Club title, The Murder at the Vicarage, followed in October of that year. By then Collins had already published, between 1926 and 1929, five Christie titles – The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, The Big Four, The Mystery of the Blue Train, The Seven Dials Mystery and Partners in Crime – in their general fiction list. As soon as The Crime Club was founded, Agatha Christie’s was an obvious name to grace the list and over the next 50 years she proved to be one of the most prolific authors – and by far the most successful – to appear under its imprint. This author/publisher relationship continued throughout her writing life, almost all of her titles appearing with the accompaniment of the hooded gunman.1

As the back of the dustjacket on the first edition of The Murder at the Vicarage states, ‘The Crime Club has been formed so that all interested in Detective Fiction may, at NO COST TO THEMSELVES, be kept advised of the best new Detective Novels before they are published.’ By 1932 and Peril at End House, The Crime Club was boasting that ‘Over 25,000 have joined already. The list includes doctors, clergymen, lawyers, University Dons, civil servants, business men; it includes two millionaires, three world-famous statesmen, thirty-two knights, eleven peers of the realm, two princes of royal blood and one princess.’

This is the first edition title page of The Murder at the Vicarage, the first Agatha Christie title to appear under The Crime Club imprint on 13th October 1930.

And the advertisement on the first edition wrapper of The A.B.C. Murders (1936) clearly states the Club’s aims and objectives:

The object of the Crime Club is to provide that vast section of the British Public which likes a good detective story with a continual supply of first-class books by the finest writers of detective fiction. The Panel of five experts selects the good and eliminates the bad, and ensures that every book published under the Crime Club mark is a clean and intriguing example of this class of literature. Crime Club books are not mere thrillers. They are restricted to works in which there is a definite crime problem, an honest detective process, with a credible and logical solution. Members of the Crime Club receive the Crime Club News issued at intervals.

As the above statement suggests, not for nothing was the 1930s known as the Golden Age of detective fiction. In that era the creation and enjoyment of a detective story was a serious business for reader, writer and publisher. Both reader and writer took the elaborate conventions seriously. The civilised outrage that followed the publication of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd in 1926 showed what a serious breach of the rules its solution was considered at the time. So, while in many ways observing the so-called ‘rules’, and consolidating the image of a safe, cosy and comforting type of fiction, Agatha Christie also constantly challenged those ‘rules’ and, by regularly and mischievously tweaking, bending, and breaking them, subverted the expectations of her readers and critics. She was both the mould creator and mould breaker, who delighted in effectively saying to her fans, ‘Here is the comforting read that you expect when you pick up my new book but because I respect your intelligence and my own professionalism, I intend to fool you.’

But how did she fool her readers while at the same time retaining her vice-like grip on their admiration and loyalty? In order to understand how she managed this feat it is necessary to take a closer look at ‘The Rules’.

THE RULES OF DETECTIVE FICTION – POE, KNOX, VAN DINE

Edgar Allan Poe: inventor of the detective story

In April 1841 the American periodical Graham’s Magazine published Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ and introduced a new literary form – the detective story. Together with four more of Poe’s stories, ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ established the unwritten ground-rules that distinguish detective fiction from other forms of crime writing – the thriller, the suspense story, the adventure story. Among the many motifs introduced by Poe in these stories were:

The brilliant amateur detective

The brilliant amateur detective

The less-than-brilliant narrator-friend

The less-than-brilliant narrator-friend

The wrongly suspected person

The wrongly suspected person

The sealed room

The sealed room

The unexpected solution

The unexpected solution

The ‘armchair detective’ and the application of pure reasoning

The ‘armchair detective’ and the application of pure reasoning

The interpretation of a code

The interpretation of a code

The trail of false clues laid by the murderer

The trail of false clues laid by the murderer

The unmasking of the least likely suspect

The unmasking of the least likely suspect

Psychological deduction

Psychological deduction

The most obvious solution

The most obvious solution

All of Poe’s pioneering initiatives were exploited by subsequent generations of crime writers and although many of those writers introduced variations on and combinations of them, no other writer ever established so many influential concepts. Christie, as we shall see, exploited them to the full.

The first, and most important, of the Poe stories, ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’, incorporated the first five ideas above. The murder of a mother and daughter in a room locked from the inside is investigated by Chevalier C. Auguste Dupin, who, by logical deduction, arrives at a most unexpected solution, thereby proving the innocence of an arrested man; the story is narrated by his unnamed associate.

Although Poe is not one of the writers she mentions in her Autobiography as being an influence, Agatha Christie took his template of a murder and its investigation when she began to write The Mysterious Affair at Styles, 75 years later.

The brilliant amateur detective

If we take ‘amateur’ to mean someone outside the official police force, then Hercule Poirot is the pre-eminent example. With the creation of Miss Marple, Christie remains the only writer to create two famous detective figures. Although not as well known, the characters Tommy and Tuppence, Parker Pyne, Mr Satterthwaite and Mr Quin also come into this category.

The less-than-brilliant narrator-friend

Poirot’s early chronicler, Captain Arthur Hastings, appeared in nine novels (if we include the 1927 episodic novel The Big Four) and 26 short stories. After Dumb Witness in 1937, Christie dispensed with his services, though she allowed him a nostalgic swan song in Curtain, published in 1975. But she also experimented with other narrators, often with dramatic results – The Man in the Brown Suit, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Endless Night. The decision to send Hastings to Argentina may have had less to do with his mental ability than with the restrictions he imposed on his creator: his narration meant that only events at which he was present could be recounted. Signs of this growing unease can be seen in the use of third-person narrative at the beginning of Dumb Witness and the interspersing of third-person scenes throughout The A.B.C. Murders, published the year before Hastings’ banishment. Miss Marple has no permanent Hastings-like companion.

The wrongly suspected person

This is the basis of some of Christie’s finest titles, among them the novels Five Little Pigs, Sad Cypress, Mrs McGinty’s Dead and Ordeal by Innocence, and the short story ‘Witness for the Prosecution’. The wrongly suspected may be still on trial as in Sad Cypress or already convicted as in Mrs McGinty’s Dead. In more extreme cases – Five Little Pigs, Ordeal by Innocence – they have already paid the ultimate price, although in each case ill-health, rather than the hangman, is the cause of death. And being Agatha Christie, she also played a variation on this theme in ‘Witness for the Prosecution’ when the vindicated suspect is shown to be the guilty party after all.

The sealed room

The fascination with this ploy lies in the seeming impossibility of the crime. Not only has the detective – and the reader – to work out ‘Who’ but also ‘How’. The crime may be committed in a room with all the doors and windows locked from the inside, making the murderer’s escape seemingly impossible; or in a room that is under constant observation; or the corpse may be discovered in a garden of unmarked snow or on a beach of unmarked sand. Although this was not a favourite Christie ploy she experimented with it on a few occasions, but in each case – Murder in Mesopotamia, Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, ‘Dead Man’s Mirror’, ‘The Dream’ – the sealed-room element was merely an aspect of the story and not its main focus.

The unexpected solution

Throughout her career this was the perennial province of Agatha Christie and the novels Murder on the Orient Express, Endless Night and And Then There Were None, as well as the short story ‘Witness for the Prosecution’, are the more dramatic examples. But mere unexpectedness is not sufficient; it must be fairly clued and prepared. The unmasking of, for example, the under-housemaid’s wheelchair-bound cousin from Australia, of whom the reader has never heard, may be unexpected but it is hardly fair. The unexpected murderer is dealt with below.

The ‘armchair detective’ and the application of pure reasoning

In 1842, Poe’s story ‘The Mystery of Marie Roget’ was an example both of ‘faction’, the fictionalisation of a true event, and of ‘armchair detection’, an exercise in pure reasoning. Although set in Paris, the story is actually an account, complete with newspaper reports, of the murder, in New York some years earlier, of Mary Cecilia Rogers. In this story Dupin seeks to arrive at a solution based on close examination of newspaper reports of the relevant facts, without visiting the scene of the crime. The clearest equivalent in Christie is The Thirteen Problems, the Marple collection in which a group of people meets regularly to solve a series of mysteries including murder, robbery, forgery and smuggling. Miss Marple also solves the murders in The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side basing her solution on the observations of others, and visiting the scene of the crime only at the conclusion of the book; she undertakes a similar challenge in 4.50 from Paddington when Lucy Eyelesbarrow acts as her eyes and ears. Poirot solves ‘The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge’, in Poirot Investigates, without leaving his sick-bed; and in The Clocks, making what amounts to a cameo appearance, he bases his deductions on the reports of Colin Lamb. For the novels of Christie’s most prolific and ingenious period (roughly 1930 to 1950), the application of pure reasoning applies. From the mid 1950s onwards there was a loosening of the form – Destination Unknown, Cat among the Pigeons, The Pale Horse, Endless Night – and she wrote fewer formal detective stories. But as late as 1964 and A Caribbean Mystery she was still defying her readers to interpret a daring and blatant clue.

The interpretation of a code

Poe’s ‘The Gold Bug’, not a Dupin story, appeared in 1843, and could be considered the least important of his contributions to the detective genre. It involves the solution to a cipher in an effort to find a treasure. A variation on this can be found in the Christie short stories ‘The Case of the Missing Will’ and ‘Strange Jest’, both of which involve the interpretation of a deceased person’s last cryptic wishes. Although the code concept was only a minor part of Christie’s output it is the subject of the short story ‘The Four Suspects’ in The Thirteen Problems. On a more elaborate canvas, the interpretation of a code could be seen as the basis of The A.B.C. Murders; and it is the starting-point of Christie’s final novel, Postern of Fate.

The Trail of false clues laid by the murderer

‘Thou Art the Man’, published in 1844, is not as well known as the other Poe stories but it includes at least two influential concepts, the trail of false clues and the unmasking of the most unlikely suspect. Although a minor theme in many Christie novels, the idea of a murderer leaving a trail of false clues is a major plot device in The A.B.C. Murders and Murder is Easy; and in Towards Zero it is taken to new heights of triple-bluff ingenuity.

The unmasking of the least likely suspect

Like its counterpart above, the unexpected solution, this was a career-long theme for Christie and appears at its most stunning in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Hercule Poirot’s Christmas, Crooked House and Curtain. The double-bluff, a regular feature of Christie’s output from her first novel onwards, also comes into this category.

Psychological deduction

Poe’s ‘The Purloined Letter’ pioneered the ideas of psychological deduction and the ‘obvious’ solution. In this type of story, the deductions depend as much on knowledge of the human heart as on interpretation of the physical clues. In Poe’s story Dupin’s psychological interpretation of the suspect allows him to deduce the whereabouts of the missing letter of the title. The Foreword to Christie’s Cards on the Table explains that the deductions in that book will be entirely psychological due to the lack of physical clues apart from the bridge scorecards. And Appointment with Death, set in distant Petra, sees Poirot dependent almost entirely on the psychological approach. Five Little Pigs and The Hollow each have similar emotional and psychological content, although both novels also involve physical clues.

The most obvious solution

Poe’s employment of the ‘obvious solution’ of hiding in plain sight (using a letter-rack as the hiding place of a letter) is adopted, though not as a solution, by Christie in ‘The Nemean Lion’, the first of The Labours of Hercules. The solutions to, for example, The Murder at the Vicarage, Death on the Nile, Evil under the Sun and The Hollow, among others, all unmask the most obvious culprits even though it seems that they have been cleared early in the story and have been dismissed by both detective and reader. In her Autobiography, Christie writes: ‘The whole point of a good detective story is that it must be somebody obvious but at the same time, for some reason, you would find that it was not obvious, that he could not possibly have done it. Though really, of course, he had done it.’

So, Christie’s output adhered to most of the conditions of Poe’s initial model, while simultaneously expanding and experimenting with them. Although Poe created the template for later writers of detective fiction to follow, early in the twentieth century two practitioners formalised the ‘rules’ for the construction of successful detective fiction. But these formalisations, by S.S. Van Dine and Ronald Knox, writing almost simultaneously on opposite sides of the Atlantic, merely acted as a challenge to Agatha Christie’s ingenuity.

S.S. Van Dine’s ‘Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories’

Willard Huntington Wright (1888–1939) was an American literary figure and art critic who, between 1929 and 1939, wrote a dozen detective novels under the pen name S.S. Van Dine. Featuring his detective creation Philo Vance, they were phenomenally successful and popular at the time but are almost completely – and deservedly, many would add – forgotten nowadays. Vance is an intensely irritating creation, with an encyclopaedic knowledge of seemingly every subject under the sun and with a correspondingly condescending manner of communication. In The American Magazine for September 1928 Wright published his ‘Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories’. Christie knew of S.S. Van Dine; some of his novels can still be seen on the shelves of Greenway House and she mentioned him in Notebook 41 (see Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks), although it is doubtful if she was aware of his Rules until long after they were written. Van Dine’s Rules are as follows:

1 The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery.

2 No willful tricks or deceptions may be placed on the reader other than those played by the criminal on the detective.

3 There must be no love interest.

4 The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit.

5 The culprit must be determined by logical deduction – not by accident, coincidence or unmotivated confession.

6 The detective novel must have a detective in it.

7 There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel.

8 The problem of the crime must be solved by strictly naturalistic means.

9 There must be but one detective.

10 The culprit must turn out to be a person who has played a more or less prominent part in the story.

11 A servant must not be chosen as the culprit.

12 There must be but one culprit no matter how many murders are committed.

13 Secret societies have no place in a detective story.

14 The method of murder, and the means of detecting it, must be rational and scientific.

15 The truth of the problem must be at all times apparent provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it.

16 A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, and no ‘atmospheric’ preoccupations.

17 A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt in a detective novel.

18 A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide.

19 The motives for all the crimes in detective stories should be personal.

20 A list of devices, which no self-respecting detective story writer should avail himself of including, among others:

The bogus séance to force a confession

The bogus séance to force a confession

The unmasking of a twin or look-alike

The unmasking of a twin or look-alike

The cipher/code-letter

The cipher/code-letter

The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops

The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops

The comparison of cigarette butts.

The comparison of cigarette butts.

Ronald Knox’s Detective Story Decalogue

Monsignor Ronald Knox (1888–1957) was a priest and classical scholar who wrote six detective novels between 1925 and 1937. He created the insurance investigator detective Miles Bredon, and considered the detective story such a serious game between writer and reader that in some of his novels he provided page references to his clues. When he edited a collection of short stories, The Best Detective Stories of 1928, his Introduction included a ‘Detective Story Decalogue’. These distilled the essence of a detective story, as distinct from the thriller, into ten cogent sentences:

1 The criminal must be someone mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow.

2 All supernatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

3 Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

4 No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need long scientific explanation at the end.

5 No Chinamen must figure in the story.

6 No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition that proves to be right.

7 The detective must not himself commit the crime.

8 The detective must not light on any clues that are not instantly disclosed to the reader.

9 The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts that pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

10 Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

But as will be seen from a survey of Christie’s output, many of the Rules laid down by both Knox and Van Dine were ingeniously ignored and often gleefully broken by the Queen of Crime. Her infringement was, in most cases, instinctive rather than premeditated; and her skill was such that she managed to do so while still remaining faithful to the basic tenets of detective fiction.

Agatha Christie’s Rule of Three

In order to examine these Rules, and Christie’s approach to them, I have grouped together Rules common to both lists and have divided them into categories:

Fairness

Fairness

The crime

The crime

The detective

The detective

The murderer

The murderer

The murder method

The murder method

To be avoided

To be avoided

Fairness

Both lists are very concerned with Fairness to the reader in the provision of information necessary to the solution, and with good reason; this is the essence of detective fiction and the element that distinguishes it from other branches of crime writing. Van Dine 1 and Knox 8 are, essentially, the same rule while Van Dine 2, 5, 15 and Knox 9 elaborate this concept.

Van Dine 1. The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery.

Knox 8. The detective must not light on any clues that are not instantly disclosed to the reader.

Christie did not break these essentially identical rules, mainly because she did not need to. She was quite happy to provide the clue, firm in the knowledge that, in the words of her great contemporary R. Austin Freeman, ‘the reader would mislead himself’. After all, how many readers will properly interpret the clue of the torn letter in Lord Edgware Dies, or the bottle of nail polish in Death on the Nile, or the ‘shepherd, not the shepherdess’ in A Murder is Announced? Or who will correctly appreciate the significance of the smashed bottle in Evil under the Sun, or the initialled handkerchief in Murder on the Orient Express, or the smell of turpentine in After the Funeral?

Knox 9. The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts that pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

Hastings has been dubbed ‘the stupidest of Watsons’ and there are times when we wonder how Poirot endured his intellectual company. And, of course, Agatha Christie herself tired of him and banished him to Argentina in 1937 after Dumb Witness, although he was to return for Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, written during the Second World War but not published until 1975. It can be argued that the intelligence of the Watson character has to be below average because it is necessary for the Great Detective to explain his deductions to the reader through the Watson character. If the Watson were as clever as the detective there would be no need for an explanation at all. If Poirot were to look at the scene of the crime and announce, ‘We must look for a left-handed female from Scotland with red hair and a limp,’ and Hastings were to reply, ‘Yes, I see what you mean,’ the reader would feel, justifiably, more than a little exasperated. And, of course, this Rule overlaps with Knox 1 (see below) in the case of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd because Dr Sheppard in that famous case was acting as Poirot’s Watson.

Van Dine 2. No willful tricks or deceptions may be placed on the reader other than those played by the criminal on the detective.

This Rule seems to negate the whole purpose of a good detective novel. Surely the challenge is the struggle between reader and writer. In essence, the writer says: ‘I present you with a challenge to spot the culprit before I am ready to reveal him/her. To make it easier for you, I will give you hints and clues along the way but I still defy you to anticipate my solution. However, I give you fair warning that I will use every trick in my writer’s repertoire to fool you but I still promise to abide by the fair play rule.’ As Dorothy L. Sayers said in the aftermath of the Roger Ackroyd controversy, ‘It is the reader’s business to suspect everybody.’

Into this category come Christie’s greatest conjuring tricks, including The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Endless Night. In both these novels the reader is fooled into accepting the bona fides of a character who is taken for granted but not ‘seen’ in the same way that all the other protagonists are. The narrator is a ‘given’ whose presence and veracity the reader accepts unquestioningly. And, indeed, the narrator’s veracity in each case is above reproach. They do not actually lie at any stage. There are certainly some ambiguous statements and judicious omissions but their significance is obvious only on a re-reading, when the secret is known. In Chapter 27 of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Dr Sheppard himself states:

I am rather pleased with myself as a writer. What could be neater, for instance, than the following? ‘The letters were brought in at twenty minutes to nine. It was just on ten minutes to nine when I left him, the letter still unread. I hesitated with my hand on the door-handle, looking back and wondering if there was anything I had left undone.’ All true, you see. But suppose I had put a row of stars after that first sentence! Would somebody then have wondered what exactly happened in that blank ten minutes?

All true; but not one reader in a thousand will stop to examine the details, especially not in the more innocent era of the 1920s, when the local doctor had a status just below that of the Creator.

Michael Rogers, in Endless Night, is also scrupulously fair in his account of his life. He tells us the truth but, as with Dr Sheppard, not the whole truth. But if we re-read Chapter 6, which recounts a telling conversation with his mother about ‘his plan’, what a new significance it all takes on when we know the truth. The ‘plan’, and even ‘the girl’, are no longer what we had originally supposed. This novel has much in common with The Mysterious Affair at Styles and Death on the Nile, as well as with The Man in the Brown Suit and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. In the first two titles, two lovers collude, as in Endless Night, in the murder of an inconvenient wife, stage a dramatic quarrel and have seemingly foolproof alibis; The Mysterious Affair at Styles also features a poisoning which happens in the absence of the conspirators. In the latter two titles, the narrator (a diarist in The Man in the Brown Suit) is exposed as the villain.

Van Dine 5. The culprit must be determined by logical deduction – not by accident, coincidence or unmotivated confession.

An example of confession (albeit not unmotivated) as a solution in Christie’s output is And Then There Were None. Here the entire explanation is given in the form of a confession. In this most ingenious novel, Agatha Christie set herself an almost insoluble problem – how to kill off the entire ten characters of the book and yet have an explanation at the end. The only solution would seem to be the one that she actually adopted – a confession. Confessions do feature in other novels, for example Lord Edgware Dies, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? and Crooked House, but only as confirmation of what has already been revealed, while Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case contains one of the most shocking confessions in literary history …

Van Dine 15. The truth of the problem must be at all times apparent – provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it.

Although tautological, this is intended as an elaboration of the earlier Rules regarding fairness to the reader. One of the clearest examples of this in the Christie output is Lord Edgware Dies where a very audacious plot is, in retrospect, glaringly obvious with all the clues staring the reader in the face. Other blindingly evident clues include the final words – ‘Evil Eye … Eye … Eye …’ – of Chapter 23 of A Caribbean Mystery; or the description of Lewis Serrocold emerging from the study in Chapter 7 of They Do It with Mirrors; or the thoughts of Ruth Lessing in Chapter 2 of Sparkling Cyanide after her meeting with Victor; or, most controversially of all, Dr Sheppard’s leave-taking of Roger Ackroyd in Chapter 4 of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

Knox 6. No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition that proves to be right.

There are, unfortunately, a few examples in Christie’s oeuvre of ‘deductions’ not based on any tangible evidence. It must be conceded that they can only be accounted for by intuition. How, for example, does Miss Marple alight on Dr Quimper in 4.50 from Paddington? And only the ‘Divine Revelation’ forbidden by The Detection Club Oath can explain how Poirot knows that Lady Westholme from Appointment with Death spent time in prison in her early life.

The crime

The crime itself did not feature strongly in the Rules, although Christie enjoyed the challenge of Van Dine 18 below.

Van Dine 7. There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel.

The first detective novel, Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1878), concerns a robbery rather than a murder, but a mysterious death is the sine qua non of most detective novels. Although she broke this Rule often in her short story output, Christie never short-changed her readers in novel form, generously providing a multitude of corpses in And Then There Were None, Death Comes as the End and Endless Night.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.