Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

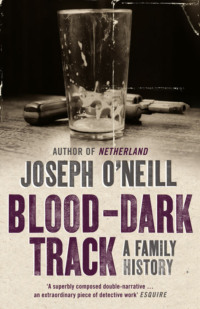

Kitabı oku: «Blood-Dark Track: A Family History», sayfa 2

But I didn’t know this for a fact. Actually, I knew just about nothing for a fact – nothing about these men, and very little about the historical circumstances of their lives.

Some might consider ignorance a virtuous trait in an inquirer, a clean slate on which evidence may impartially be inscribed. But it doesn’t work like that, at least it did not in my case. I was, of course, prejudiced; and, like most prejudices, mine found an infantile manifestation. It was not simply that my grandfathers stood accused in my mind of offences that I had not even formulated: it was that I didn’t like their faces. I didn’t like Jim’s face – there was something frightening about his handsome, tooth-baring smile – and I didn’t like the face of Joseph either, in particular the black moustache that made me think of Adolf Hitler.

What had they done wrong, though? Was it connected to their imprisonment? What were the facts?

It so happens that I am, by my professional training, supposed to be equipped as anybody to answer these sorts of questions and set to one side the kind of prejudice I have mentioned. I am a lawyer; more precisely, since lawyers are varietal as butterflies, I am a barrister working mainly in business law. It is a charmless but profitable field. There are countless commercial transactions effected every day, and they give rise to countless disputes. Were the goods defective? Did the surveyor give the bank negligent advice as to the value of a property development? Was there a material non-disclosure entitling the insurer to avoid the policy? For much of my working life I have gone into my chambers, pulled out ring binders from my shelves and tried to get to the bottom of these sorts of hard-boiled questions. After I have gone through hundreds of pages of correspondence, pleadings, affidavits and attendance notes, and sifted the relevant from the discardable, there are further, more finicky sub-questions. What was said in the telephone conversation of 14 February 1998? When did the cracks first appear in the wall? Who is Mr MacDougal? Often, meetings with the client are required to fill in the gaps or to quiz him closely to make sure nothing of significance has been left out. What one learns, pretty quickly, is that frequently the truth remains anybody’s guess – even after all the documents have been scrutinized, all the witnesses have been grilled, and all the solicitors, juniors, silks and experts, racking up fees of hundreds of thousands of pounds, have trained their searchlights into the factual darkness.

Sometimes, however, something is illumined that is strange and unlooked-for and that, although perhaps not decisive of the hard-boiled question, twists the case and gives it a new meaning. This is, in a sense, what transpired after I began to look into the unknown lives of Joseph and Jim, following the narrow beam of their coincidental imprisonment. It led to times and places in which politics might have dramatic and personal consequences; in which people might be impelled to act or acquiesce in the face of evil and embark on journeys of the body and spirit that to many of us, living in the democratic west at the beginning of the new century, may seem fantastical; and in which people might through political action or inaction discover boundaries in themselves – good and bad – that we, casting our vote twice a decade, or losing our temper at the dinner table, or shunning the wines and cheeses of France, maybe cannot hope to know. Maybe. It may be, in fact, that our lives are thrown into greater ethical relief than we suspect. We may be judged strenuously by our descendants, who will perceive distinct rights and wrongs, shadows and crests, that we failed to notice. In part, my grandfathers’ predicaments stemmed from what they saw or did not see around them. To this extent, they stand as paradigms of political and moral visions of different sorts, the blind eye and the dazzled eye, each with its own compensations and each with its own price.

1

… the old post cards do not depict Maurilia as it was, but a different city which, by chance, was called Maurilia, like this one.

– Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

I was born on 23 February 1964 in the Bon Secours Hospital, Cork. The following day my father flew into Cork and went directly from the airport to the nursery ward, where to everybody’s amazement he unhesitatingly picked me out from the sixteen newborn babies lying anonymously in their cots. Then he walked quickly to the maternity ward to see my mother. She was in bed, and my father sat down on the rim of the bed. He took her hand. He had been abroad working, and it was their first meeting for over a week. ‘Your father has died,’ he said. My mother began to weep, and so did my father.

Born the day after his death, I was given my grandfather’s name – Joseph.

He died on a rain-blurred day in Istanbul. At some point in the afternoon, Pierre, my mother’s brother, sat grieving alone in an Istanbul café. A concerned stranger approached the tearful young man and gently asked him what his trouble was. ‘My father has died,’ Oncle Pierre said. The stranger took hold of Pierre by the shoulders and looked him in the eyes. ‘See to your mother,’ he said.

Joseph had for years been troubled by a heart problem that necessitated trips to Istanbul for treatment; and in 1961, he suffered a heart attack that brought Oncle Pierre, who was in Lyon studying law and economics, back to Mersin to help his father with the completion of the new Toros Hotel building. Joseph’s condition worsened. In January 1964, when Fonda Tahintzi went to ask for the hand of my aunt Amy, he found Joseph in bed, dressed in his bathrobe and too weak to rise. In February, X-rays of my grandfather’s heart were taken; these were, according to the Mersin doctors, inconclusive. Joseph appealed for help to Muzaffer Ersoy, his former personal physician, in whom he had great faith. Dr Ersoy, who had moved his practice to Istanbul and was on his way to substantial professional fame, requested that the X-rays be sent to him. Once he’d seen them, he responded immediately. The Mersin doctors had misread the X-rays: far from being inconclusive, they showed that the patient’s heart had suddenly enlarged; it was vital that he go to Istanbul immediately for further treatment and tests. Joseph’s worst fears were confirmed: for days, now, he had been vomiting in the mornings, grimly muttering, ‘J’aime pas ça.’ So, wearing a hat placed on his head by Amy, Joseph caught a flight at Adana. It was his first experience of aviation, the death of a friend in an air crash having previously scared him off. On this occasion, though, getting on board the aeroplane truly was a matter of living or dying. Dr Ersoy said that the next three days would be decisive; either the patient would perish or the crisis would pass. Joseph said to his wife, Georgette, ‘I promise that if I survive I’ll buy you a fur coat. I’ll buy one for you and one for the wife of Muzaffer Ersoy.’

Nobody got a fur coat. On the third day of his hospitalization, Joseph died; but not before he had seduced my grandmother one last time. Lying on his bed, he asked her forgiveness for all the harm he’d caused her: ‘Pardonne moi pour tout le mal que je t’ai fait.’ Mamie Dakad replied, ‘I am very happy with what I have had.’ My grandfather closed his eyes. For a long time he had worried terribly about dying, but now he was surprisingly and suddenly at peace. ‘Comme c’est bon,’ he said, and he squeezed his wife’s hand; whereupon he died.

My grandmother attached great weight to these dramatic gestures and would occasionally tell the story of her husband’s last moments to her daughters. It was, in her eyes, a kind of happy ending, and one which decisively vindicated the steadfast and exclusive love she had borne my grandfather for over thirty years. My mother said to me, ‘Because of what he said in the hospital, Maman always kept a good memory of Papa.’

A van came down overnight from Istanbul with the body. The journey was not easy. Snow was falling as the van crossed the Anatolian plateau, a near-desert of desolate, immeasurable darkness. The van slowly made its way through the snowstorm, the flakes falling without cease and still falling hours later as the vehicle slowly climbed the Taurus mountains, where, at the village of Pozanti, Fonda and Amy escorted it for the remainder of the journey. The convoy proceeded through forests and along terrifying precipices towards a narrow chasm known as the Cilician Gate, through which the army of Alexander the Great and the crusaders of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, once passed. Eventually the snow and the mountains gave way to heavy rain and foothills, and finally to drizzle and the maritime plain of Çukurova, which is still referred to by westerners as Cilicia, after the Roman province (briefly governed by Cicero) of which the plain formed part. My grandfather’s body was driven through Tarsus, the birthplace of St Paul, where a still-visible hole in the ground is alleged to be the well in which the evangelist hid from his pursuers. Legend also sticks to Tarsus’ river, the Cydnus, on whose then navigable waters Cleopatra sailed her barge to meet Mark Antony. The convoy continued south-westward for about thirty kilometres, coming to a place that according to one conjecture is the location of Eden, a theory that, however crazy, is consistent with the remarkable fertility of the local earth, in which superb fruits and vegetables grow, and also with archaeological evidence (produced by the excavations of an English Hittitologist, John Garstang) which suggests that the area – that is, the area now occupied by the city of Mersin – is one of the oldest continuously inhabited spots on the planet.

The van followed Fonda’s car along an avenue of eucalyptus trees. This was the eastern road into Mersin. On they went: past the railway line that reaches a charming terminus at Mersin’s old railway station, past the courthouse, past the prison, past what used to be known as the Maronite quarter, past the Catholic church, past the old Greek quarter. They entered a town which I imagine I just about remember, a quiet port of white-stoned villas and lush gardens, of untidy shacks and donkeys loaded with panniers leaking peaches, of card-games and tittle-tattle in multiple languages – a town reeking, in the springtime, of orange blossom. There was practically no motorized traffic as the convoy proceeded up the main street, Atatürk Çaddesi, and drove by the Toros Hotel, whose transformation – two large old limestone houses knocked down and replaced by a single, brand-new, four-storey building with fifty-three rooms – Joseph Dakad had only recently completed. The only other vehicles of any size on the street were cabs, which is to say, red-spoked carriages drawn by two blinkered horses whipped into exhaustion.

As recently as the early ’seventies these squeaking, rocking contraptions were Mersin’s main form of taxi transport, and I often boarded them with my tiny, hunchbacked great-aunt, Tante Isabelle, to go from the hotel to the little stone house she shared with her tiny, hunchbacked sister, Tante Alexandra. Shaded by the cab’s tassel-fringed bonnet, mesmerized by the carriage’s brassy curves and the horses’ flying red pom-poms, surrounded by the odours of dung and Tante Isabelle’s Turkish eau-de-Cologne, I settled back in the scarlet leather seat like a pocket pasha and waited for the jolt that signalled the start of a ride of heavenly unsteadiness. We took the route taken by the convoy six or so years earlier, past rows of splendid palm trees that seemed to stand to attention, the whitewashed bases of their trunks smart as the spats worn by the Turkish soldiers who, to my delight, seemed constantly to march and parade on the streets of Mersin, often with glorious rockets and artillery on display. ‘Dooma, dooma, doom,’ I chanted from my great-aunts’ balcony in imitation of the drums. I loved the invasion of Cyprus in the summer of 1974, when Mersin was filled with troops and there was a blackout in case the Greeks bombed the town.

We clip-clopped past the official house of the Vali (the provincial governor), past the monumental Halkevi (the House of the People) and its seaward-gazing statue of Atatürk, and then past the Greek Orthodox Church. At the rear of the church was the priest’s house. It overlooked an open-air cinema where shadows of bats flitted across the screen. I could not follow the films – I half-remember tragic melodrama involving disastrous migrations from country to city – or why the paying public, massed amongst winking red cigarette tips, intermittently snapped into fierce, sudden applause, the men rising from blue wooden chairs to clap with frowning, emotional faces. Peering through the rear window with my great-aunt and the priest’s family, I looked out on a world full of stories I did not understand.

After the Greek Orthodox Church, the carriage jingled past big merchants’ houses, some semi-abandoned, most in disrepair. In the top corner of each, it seemed, lived an old lady whom one knew – Madame Dora, Madame Rita, Madame Fifi, Madame Juliette, Madame Virginie. It was a leafy street, and turtle doves purred in the trees. On we went, hoofbeats clacking, the gentle stink of horseshit wafting up from the street, until we came to Camlibel (pronounced Chumleybell), a small oval park surrounded by villas with gardens that overran with fruit trees and bougainvillaea. At the far end of Camlibel was the Dakad residence, a large, cool, rented apartment on the first floor of a villa. Tante Isabelle’s place was only a little further on, just before the military barracks at the edge of the town. That was the long and the short of Mersin in those days: a quarter-hour ride in a carriage, or a five minute drive for a slow-moving car such as the van transporting the body of Joseph Dakad to Camlibel.

If you drove out west of Mersin, you travelled along a beautiful coastline. Once you had passed through the avenue of palm trees by the barracks, crossed the dry riverbed and gone past the stadium of Mersin Idmanyurdu (the football team that has always yo-yoed between Turkey’s first and second divisions), in a deafening roar of frogs you came upon mile after mile of orange groves and lemon groves planted, at their perimeters, with pomegranate, grapefruit, tangerine, and medlar trees. Then came the villages of Mezitli and Elvanli and Erdemli, the Taurus foothills meanwhile getting closer and closer until, after you’d motored for the best part of an hour, the farmland expired and the road was hemmed in by, on the left, the sea – which indented the land with bays that flared turquoise at their confluence with freshwater streams – and, on the right, rocks covered with wild olive trees, sarcophagi, basilica, aqueducts, castles, arches, mosaics, ruined temples and ghost villages. You drove on until you came to Kizkalesi, an island fortress wondrously afloat three hundred yards offshore that is a relic of the medieval kingdom of Lesser Armenia, and you got out of the car and went swimming in hot, lucid waters. There was nobody else around except for the occasional camel or shy children hoping to be photographed.

In the last twenty years, the beach holiday has arrived in Turkey. Nowadays Kizkalesi is a swollen, chaotic resort crowded by tourists from Adana and the landlocked east. The roadside antiquities are dwarfed by advertising hoardings, pansiyons and summer homes, the inlets and creeks are covered by a mess of unplanned structures, the citrus groves have been razed to make way for holiday complexes and towering, gloomy suburbs. The belching frogs have gone (some, decades ago, packed in ice and shipped by Oncle Pierre to the tables of France), and an hour’s drive will barely take you clear of Mersin’s concrete outskirts and the moan of cement-mixers and the fog of building dust.

In Mersin itself, a huge boulevard now swings along the seafront. Countless young palm trees spring from the pavements, new stoplights regulate the chaos at junctions, traffic islands are dense with flowering laurels, and block after block after block of bone-white apartments take shape from grey hulks. Hooting minibuses race through the streets three abreast, residential complexes multiply along the coast, the minarets of enormous new mosques make their way skywards in packs. In the final thirty years of the last century, the population, swollen by a massive influx from the east, much of it Kurdish, has multiplied sixfold to around six hundred thousand. It’s a boomtown. The port, with its officially designated Free Trade Zone, ships’ commodities worldwide in unprecedented quantities: pumice-stones from Nevsehir to Savannah and Casablanca; pulses from Gaziantep to Colombo, Karachi, Chittagong, Doha and Valencia; apple concentrate from Niğde to New York and Ravenna; TV parts from Izmir to Felixstowe and Rotterdam; insulation material from Tarsus to Alexandria and Abu Dhabi; dried apricots from Malatya to Antwerp (and thence Germany and France); Iranian pistachios to Haifa (in secret shipments, to save political embarrassment); Russian cotton to Djakarta and Keelung; citrus fruit from Mersin to Hamburg and Taganrog; synthetic yarn from Adana to Norfolk and Alexandria; carpets from Kayseri to Oslo and to Jeddah. Just along from the new marina, you’ll find a Mersin Hilton and luxury seaside condominiums; and in the unremarkable interior of the city, the gigantic Mersin Metropol Tower (popularly known as the dick of Mersin) lays claim to the title of ‘the tallest building between Frankfurt and Singapore’. On the streets, young women are turned out in European trends, teenagers smooch, and male students at the new Mersin University amble along Atatürk Çaddesi, Mersin’s first pedestrianized street, with long hair and clean-shaven faces.

Of course, some things never change. Sailors still sport snowy flares. Men wear vests under their shirts in the clammy August heat, and moustaches, and old-fashioned trousers with a smart crease leading down to the inevitable dainty loafer. You’ll still see vendors pushing carts loaded with pistachios, grapes, or prickly pears; corn on the cob (grilled or boiled) is sold at street corners; and shoeblacks grow old behind their brassy boxes. The old vegetable and meat and fish market has kept going, and the pleasant little Catholic Church of Mersin where my parents were married and which I have intermittently attended over the years is the same. As ever, a fountain spurts a loop of water in the church’s small, leafy courtyard, and Sunday Mass attracts adherents to all six Catholic rites – Roman, Syrian, Chaldaean, Maronite, Armenian, and Greek. It’s a varied congregation. You’ll see ageing westernized Christians in drab urban clothes, enthusiastic children packed in scrums into the front pews (boys right of the aisle, girls left), and a big turn-out of worshippers vividly dressed in shawls and baggy pants; these last are Chaldaeans from the mountains in the extreme south-east of Turkey. Not all Mersin Christians are rich.

But old Mersin – the Mersin to which my grandfather’s body returned, a town of verandas, gardens and large stone houses – has largely disappeared. One by one, the villas have been sold, knocked down and replaced by tower blocks. The last surviving villa of the Naders, my grandmother’s family, is in Camlibel. The fate of this elegant building, which until only a few years ago was occupied by my mother’s cousin Yuki Nader and his Alexandrian wife, Paula, is not atypical. Surrounded on all sides by tower blocks whose occupants bombard it with junk, it is boarded up and empty – awaiting the bulldozer or, I’ve heard it rumoured, conversion to a bank – its avocado trees, shutters, gates, even its footpath stones, ripped out by persons unknown. Nobody seems to notice or, more precisely, attach significance to this spectacle.

A few other places survive. An ancient Nader property is now a primary school, and in the old Maronite quarter, the house where Joseph Dakad grew up is in use as a police station.

For what it is worth, I like the new city and am excited by it. I know what fantasy and work and guts underpin its progress, I know that with its parks, shops and up-to-date facilities it is a pleasant, utilitarian and altogether desirable place to live – a model Turkish city, in many ways. But because of its modern, commercial character, Mersin has no place in western European narratives. British guide books, for example, are unanimously dismissive: ‘Can serve as an emergency stop on your way through,’ is the assessment of one book, ‘none too attractive’ and ‘almost without interest’ of others. One guide book asserts that the city was ‘little more than a squalid fishing hamlet’ at the beginning of the twentieth century, while another declares that the place did not even exist until fifty years ago.

Although Mersiners would probably find hurtful and wrong the notion that their city is nothing more than an ugly point of onward transit, it is likely that they would agree, without anxiety, with the suggestion that it has no past to speak of. Very few families have been rooted in the town for more than a generation or two, and most have histories connected to distant Anatolian villages or Kurdish mountainsides. No collective stock of stories or postcards of the old Mersin circulates, and no real interest exists in the handful of crumbling stone buildings that appear here and there, without explanation, between the apartment blocks. What matters overwhelmingly is the here and now, and so Mersin is unmythologized and ghostless, and contentedly so. Of course, it is not exempt from the generic Kemalist myth and, like every other urban settlement in the Turkish Republic, it is haunted by Atatürk, whose image, in a variety of get-ups, attitudes, silhouettes and situations, continues to adorn schools, shops, offices, homes, buses, stamps, bank notes and public spaces. (How many millions of times is a Turk fated to behold that wise, subtly pained visage?) If the past has any meaning, it is as a realm of Kemalist socio-economic progress: the only printed history of Mersin that exists, an illustrated book produced by a local lawyer, concentrates on municipal achievements like the reclamation of seaside land, the construction of the modern port, the creation of the waterfront park.

Atatürk famously visited the city in 1923. He stayed in an imposing mansion of white stone and red rooftiles that, with its ballroom, its huge mountain-facing balcony and its lush garden, was Mersin’s best shot at a palazzo. In recent years the house has been meticulously restored. Decades of grime have been scraped from its walls, shutters have been replaced and metalwork renewed. It has been named Atatürk’s House, and for a small fee visitors may stroll about its rooms to admire the enormous proportions of the building and the painted ceilings and the period furniture, and to try to envisage the great leader breakfasting here or consulting with his adjutants there or, as happened on 17 March 1923, stepping out on to the wrought-iron balcony at the front of the house and shouting at the crowd gathered below – for reasons it took me a long time to fathom – ‘People of Mersin, take possession of your town!’

A tiny and dwindling number of Mersiners will never really think of the big house as Atatürk House. For them, it will always be the Tahintzi house, the house where my uncle Fonda and his forebears lived. Fonda himself says that the house used to be known as the Christmann house, after Xenophon Christmann. The Christmann family arrived in the Levant as part of the entourage of the German Prince Athon, who was summoned to Greece in the 1830s by prospectors for a Greek royal family. Xenophon Christmann wound up as the German consul in Mersin, married Fonda’s great-aunt, and spent a chunk of his fortune on building the most magnificent building in the town. Years later, when Atatürk requisitioned the residence and the Tahintzi family standoffishly withdrew into a wing of the house, the Gazi (warrior of Islam) took offence and demanded, ‘Where is the lady of the house?’

My grandmother had a tale of this kind – a colourful jelly of small facts in which the family origins are suspended and conserved. She said that her patrilinear ancestors, the Naders, came to Turkey from Lebanon. The arrivals were two brothers from Tripoli – les grandpères, she called them both, although only one, Dimitri, was her grandfather – who were in the business of shipping timber cut from the fir and juniper forests of the Taurus Mountains to the Suez Canal. The buyers of the timber offered to pay with gold or, if the brothers preferred, shares in the Suez Canal Company. The Nader brothers chose gold, and with it they bought land in the burgeoning port of Mersin. They planted orchards and, in 1875, built two large stone houses for themselves on Mersin’s main drag. The houses formed a single immense building two stories high and a block wide, with the ground floor given over to commercial units; sixty or so years later, these premises were transformed by my grandfather into the Toros Hotel.

Such fragments of lore aside, the Christian community is fully implicated in Mersin’s general lack of retrospection. I never grew up with a clear sense of what these strange French-speaking Turks were doing in Mersin, or who they – we – really were. I knew that some families had connections with Lebanon, but I had little idea of what that meant. We were in Mersin now, and there was very little else to say.

In order to gain a picture of historic Mersin, I had to leave the city – leave Turkey, in fact – and track down the writings of travellers kept in European libraries. I read that in 1818, when Captain Beaufort went there, Mersin consisted of nothing more than a few wretched huts raised on piles. Some years later, a long-term English resident of Tarsus called William Burckhardt Barker noticed that on the slightest appearance of bad weather, Arab lombards from Syria would take shelter at a spot known as Zephyrium, or Mursina, where the roadstead was excellent. Mursina was a name derived from the Greek for myrtle, because immense bushes of that plant were practically the only thing to characterize the site. In 1838, there were only a few magazines and huts there, and bales of cotton were left out in the rain until French vessels arrived to ship them to Marseille. Barker saw an opportunity. He built large warehouses capable of holding the cargoes of fifteen vessels at one time, and soon these were filled with the produce of the hinterland for export: cotton, wool, wheat, barley, wax, sesame-seed, linseed, madder-roots, Persian yellow-berries, hides. Imports – sugar, coffee, indigo, cochineal, soap, Persian tobacco – also brought traffic to the area, and before long others had built magazines and settled there.

However, a Frenchman who visited Mersin in 1853, Victor Langlois, saw only a damned, marsh-covered, fever-devastated land with a population that decreased every year; the air was lethal, the water insalubrious, the fruit harmful. (He was not exaggerating: in the Adana plain, entire colonies of Circassian refugees, escaping from Russian anti-Muslim oppression, would be rubbed out by malarial fever.) By April 1875, things had noticeably improved. The Reverend E.J. Davis, arrived from Egypt, gained the impression of a bustling scala whose success he attributed to the active demand for cereals consequent upon the Crimean War. Mersina, as the port was known to westerners, struck the Reverend as a ‘flourishing little place; its bazaars, thronged by the various races who have settled here, present a scene of great animation; some of its streets are paved with square blocks of limestone; and there are many really good stone houses’. Officials apart, the Reverend observed, very few Turks lived in Mersin: ‘As usual in ports of these regions, Greeks and Christians of Syria are the principal inhabitants – the Greeks being energetic, enterprising, and many of them rich. The purely European residents are very few in number; an unhealthy climate and the lax commercial morality of the place, render it almost impossible for a European to thrive, or even live there.’ He noted that nearly all the Syrians spoke French – ‘it is remarkable how great an influence France has had upon the Roman Catholic population of Syria’ – and was impressed by the Greek hospital and church and, especially, the Greek school (which, forty years later, my grandmother would attend), where masters fluent in French taught ancient and modern Greek, sacred history, French, geography, arithmetic. Then, in July, when he returned to Mersin to catch a steamer home, Davis saw a dark side of the town that almost cost him his life. Descending from cool mountains, he was horrified by an intensely humid and enervating heat and the spectacle of sick people lying on mattresses at the door of their houses. To make things worse, cholera had appeared in Syria, and the service of the Russian steamers had been suspended due to a ten-day quarantine imposed by the Ottoman government on all arrivals from Syria. Davis was forced to sweat it out in Mersin. He almost didn’t make it. With the whole town in the grip of fever, and funerals passing regularly under his windows, and sleep impossible during nights he compared to a ‘damp, yet hot, oven,’ Davis fled for the relative relief of Boluklu, a village in the foothills about an hour’s ride away, where the air was marginally better. He stayed in the Mavromati house – the house, that is, of my uncle Fonda’s great-grandfather. Eventually, after eight feverish days during which he lay tormented by horrid dreams and visions, he booked a passage on a French mail steamer to Marseille and escaped Mersin’s ‘entrancing beauty and deadly air and heat’.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.