Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Beauty and Atrocity: People, Politics and Ireland’s Fight for Peace», sayfa 2

It will take a lot to create just one history, however. The sense and depth of history arises out of continuity, out of a firm linkage of people to place. In parts of Northern Ireland surnames have remained constant for many hundreds of years, and this has created a society where family and community count for a great deal. As one nationalist put it, ‘When we want to get something done here, we phone a cousin.’ In the north, four hundred people can show up to a funeral, and when somebody is shot dead the lives of hundreds can be directly affected. With this continuity comes a sense of history and identity that is rarely questioned.

One Belfast man, whom I met early on in my travels, gave me a warning: ‘All that everyone will say to you here – no matter how much of it seems to be foregrounded on fact – it’s all subjective experience. None of it is true. There is no truth in this place. Anyone who gives you the true version, well, you know immediately not to trust them.’ He had offered me a liar’s paradox: if a Northern Ireland man tells me that in Northern Ireland people don’t tell the truth, how can I believe him? Riddles aside, I was to hear many ‘true versions’ over the coming months, from the senior politician who cheerfully informed me that Catholics cannot be considered Christians, to the ex-IRA man who was certain that the British government retains a strong strategic interest in Northern Ireland. A lot of the time, however, these ‘true versions’ would consist of interpretations that sounded plausible until somebody else said something just as plausible but wholly contradictory. I was to find myself deluged by such declarations of identity. At times I would listen with interest, at other times with weariness – and sometimes with something close to jealousy. Louis MacNeice wrote of his native Northern Ireland:

We envy men of action Who sleep and wake, murder and intrigue Without being doubtful, without being haunted. And I envy the intransigence of my own Countrymen who shoot to kill and never See the victim’s face become their own Or find his motive sabotage their motives.

It is quite possible for an outsider to feel envy in the province, a place seemingly free from doubt. My own world of moral equivalence, where one is not encouraged to pass judgement on the beliefs of others, can seem, by comparison, to be a place without conviction. How fortifying it must be to have something always to believe in, and somebody always to react against. Is this what Dominic Behan wrote about in his lovely song, ‘The Patriot Game’: ‘For the love of one’s country is a terrible thing, it banishes fear with the speed of a flame, and it makes us all part of the Patriot Game’?

Now flip the coin. Perhaps Northern Ireland is a place where judgement is too readily passed. It has produced people prepared to die, prepared to cut off a hand for the cause, but not prepared to make lesser compromises. A weaker identity might produce a stronger society. One Belfast republican told me of time spent, many years previously, in Coventry. There he became friendly with a local Labour Party activist, but he could never understand how someone could be politically active in a ‘twilight city’ where nothing ever happened, where the construction of a zebra crossing was held up as a political achievement. For many in Northern Ireland, politics is not about the mundane or the consensual, it is about the struggle of identities: them and us. Why give a damn about helping kids across a road when there is an identity to preserve?

Alongside intensity of belief can sit self-importance. When a great deal of time is spent gazing inwards, it is possible to lose – or fail to gain – perspective on one’s position in the world. MacNeice again, this time seething with indignation:

I hate your grandiose airs, Your sob stuff, your laugh and your swagger, Your assumption that everyone cares Who is the king of your castle.

In a speech to the House of Commons in 1922, Winston Churchill (a member of the Liberal government team that negotiated the Anglo-Irish treaty with Michael Collins, and, according to his bodyguard, the subject of an attempted assassination by the IRA the previous year) noted that while the First World War might have overturned great empires, and altered ways of thinking across the globe, it had not changed attitudes everywhere: ‘As the deluge subsides and the waters fall short, we see the dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone emerging once again. The integrity of their quarrel is one of the few institutions that has been unaltered in the cataclysm which has swept the world.’ Churchill’s speech has often been quoted to underline the unchanging nature of Northern Irish politics. Yet it is his perception of people so unaffected by world events, so in thrall to their own reflections, that is most striking.

Seventy-nine years later Northern Ireland would gain a perspective of its position in the world. On 11 September 2001, as Al Qaeda mounted a raw and shocking attack on New York City, the Troubles were suddenly made to seem stale, predictable and petty. Blinkers fell away as all parties were forced to look beyond themselves, and to accept that men with stronger senses of identity were now commanding the world’s attention. Fewer people – in particular fewer Americans – now cared who was the king of their castle. September 11 was an attack on all that the world understood, and it shook some of the certainty and self-importance out of Northern Ireland. In its aftermath the move towards peace accelerated.

Not long after I arrived in Belfast, I met a man who told me a story. He had been sitting at home with his wife and small daughter, watching the film Schindler’s List. During a brutal camp scene the man’s wife leant across to him and whispered, ‘Is that what your prison was like?’ The man, a former member of the IRA who had planted bombs, shot at British soldiers, and served time in jail, explained that however hard prison had been for him, however brutal the screws, his treatment could not be compared to that of concentration-camp inmates. The next day, as he drove his daughter to school, the little girl asked him whether he’d really been in prison. ‘Yes.’ ‘But aren’t prisons for bad people?’ ‘Not always. You saw the film last night? Those prisoners weren’t bad people. They were put in prison by bad people. Sometimes the bad people aren’t the prisoners.’

These are the words of a father explaining his past to his daughter, but they could easily be addressed to the world at large. Over the course of this book we will encounter people who have done things that most would consider unacceptable. Some have placed morality to one side more readily than others, but how many of them now consider what they did to be wrong? Some may see their acts as having been politically motivated, in defiance of an unjust system, or in defence of their communities. These may not have been the only – or sometimes even the primary – reasons for their behaviour; they could be handy rationalizations, cynical assaults on a morally sustainable position. But they could also be sincere responses to a complex history, and they may explain why one likeable man feels able to compare his captive status, if not his actual treatment, to that of a Holocaust victim. So how should we approach men who used violence – other than with great care? Is it wrong to judge people in terms of absolutes? While a man may have committed terrible acts in certain situations, in all other areas of life he may have behaved in an entirely moral fashion. If he believes that he had right on his side, can we take him at his own estimation of himself?

We will meet those who suffered the direct consequences of these terrible acts. One man, an ex-police officer – who was himself injured in a bomb attack – told me of arriving at the scene of an explosion to find a friend and colleague lying dead. His reaction had not been one of anger or vengeance, but sadness and a sense of futility. He told me how he would have loved to bring the people responsible down to the scene, where he could ask them exactly what uniting Ireland was about.

We will meet those who never used and sometimes never endorsed violence, but who are entrenched in traditional ways of thinking: people from the Protestant tradition who consider themselves British at a time when Britishness is losing its meaning and relevance for the English, Welsh and Scots; people from Catholic backgrounds whose lives have been devoted to reuniting with the Irish Republic despite its lack of interest in reuniting with them. Slighted by their chosen partners, many of these uneasy neighbours now stand together under the umbrella of the Good Friday Agreement. What divides them unites them.

It is important to remember that the overwhelming majority of people in Northern Ireland, whether Orange or Green, did not participate in, or support, the violence of the Troubles. Yet many of them were affected by it. In 1999 researchers from the University of Ulster published the ‘Cost of the Troubles Study’, for which they had interviewed 3,000 men and women across Northern Ireland to gauge the effects of the Troubles on ordinary people. Of those interviewed, a quarter had seen people killed or injured, a fifth had experienced a deterioration in their health which they attributed to a Troubles-related trauma, and almost one in twenty had been injured in a bomb explosion or a shooting. As well as recording a large increase in alcohol consumption and the taking of medication, the study found a high level of fear of straying from one’s own area and an acute wariness of outsiders.

The ‘Cost of the Troubles Study’ opens up a vista on a world beyond belief and self-importance. It is a world with few spokesmen, but plenty of inhabitants. These are the people whose voices were rarely heard in the reports that filled the English newspapers. One man told me of sitting in a bar on the Falls Road, listening to some old-time republicans boasting of the length of time they’d spent in prison. After a while another man tired of what he was hearing. ‘Fucking lucky for you!’ he shouted. ‘You done twenty years sitting in a safe wee cell? And your family provided for? What about the poor man who had to go out to work every morning, risking fucking death? You were in a fucking sanctuary!’

At the junction between the two worlds, an act of common kindness could attract recrimination. A Catholic man from Claudy told me how he had once tended a policeman who had been shot in the street. He put a tourniquet around the policeman’s leg and sat with him until an ambulance arrived. A while later, at his holiday home across the border in Donegal, an IRA man on the run approached him and asked why he had helped the policeman. He replied that he would have helped a dog if he had needed it. ‘In fact,’ he added, ‘I might even have helped you.’ Days later he was threatened: ‘We’re very worried for you and your family so long as you stay here…’ I asked him how republicans in one town had known of an incident that occurred in another. ‘Kick one of them,’ he said, ‘and they all limp.’

One man who spoke for the citizens of the stifled world was Seamus Heaney. Heaney, a Catholic from Derry, was once asked by Sinn Féin director of publicity Danny Morrison, ‘Why don’t you write something for us?’ ‘No,’ replied Heaney, ‘I write for myself.’ His poem ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’ gives voice to a passive people, too cowed to speak out against ‘bigotry and sham’. According to Heaney, ‘smoke signals are loud-mouthed compared with us’. The poem ends:

Is there a life before death? That’s chalked up In Ballymurphy. Competence with pain, Coherent miseries, a bit and sup, We hug our little destiny again.

A ‘little destiny’ is not much of a thing to hug. It is hardly surprising that so many of the people of Northern Ireland, once denied a life before death, now fear a return to the Troubles; nor is it surprising that tens of thousands of these people gathered in Belfast, Derry, Newry, Lisburn, and Downpatrick to rally for peace in March 2009 in the wake of the dissident killings.

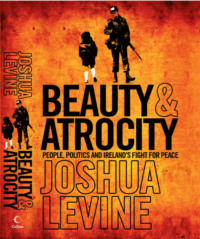

And yet ‘The Grauballe Man’, another of Heaney’s poems from the same collection, includes the words ‘hung in the scales with beauty and atrocity’. Echoing W. B. Yeats, who spoke of ‘a terrible beauty’ born of the 1916 Easter Rising, Heaney is daring to hint at a beauty to the modern Troubles. While giving a voice to those silenced by the violence in one poem, he is suggesting a nobility to that violence in another.

Northern Ireland is built on such contradictions. It was created as a political compromise to bring an end to conflict, but conflict has flourished within it. It goes by the name of ‘Northern Ireland’, but its northernmost point lies to the south of part of the Irish Republic. Its people are divided by religion, but their quarrel is not religious. And while they are divided, they are also united. As a man once said, ‘If you understand Northern Ireland, you don’t understand Northern Ireland.’

As I eased my way into this world of divided, united people, I made my first base just outside the pretty town of Killyleagh, on the banks of Strangford Lough in County Down. I was staying with the Lindsays, a warm and generous family who had never met me before yet welcomed me like an old friend. Katie, their daughter, is a talented artist who works with patients at the Mater Hospital in Belfast. Their lives were a world away from my own in London, but I quickly became very adept at lighting a wood fire, and sitting by it with a glass of whisky. Through the Lindsays I had the fortune to meet Bobbie Hanvey, a photographer, writer, broadcaster, and one-time nurse in Downshire mental hospital, a man described by J. P. Donleavy as ‘Ireland’s most super sane man’.

Bobbie hosts a programme, The Ramblin’ Man, every Sunday night on Downtown Radio, in which he interviews local personalities. His easy-going charm allows him to get away with asking some very awkward questions. He prised several seconds of rare silence from Ian Paisley by asking him whether, had he been born a Catholic, he could have been a member of the IRA. It cannot be easy for Paisley to accept that God could have made him a Catholic, never mind that he could have been a member of the IRA. The eventual answer was, ‘No, I don’t think so,’ followed by an unprovoked denial that he had ever supported loyalist violence. A Hanvey trademark is the undercutting of a serious subject with a flash of mischief. He interrupted the ex-leader of the UVF, in mid flow on the subject of large booby traps, with the observation that the biggest booby trap he’d encountered was a brassiere. He also advised a Chief Constable of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), who had once worked in vice, to write a memoir with the title Pros ’n’ Cons. Nonplussed, his guest thanked him for ‘that very impressive suggestion’.

But Bobbie’s irreverence cannot mask a keen intellect and a shrewd understanding of the complexities of Northern Ireland, from which he seems to stand aloof, friendly with men and women of all sides. I would become very grateful for his insights, and even more grateful for the chance to quote from his interviews in this book. One of my abiding memories of my time in Northern Ireland is of an evening spent upstairs in his Down-patrick house, listening to recordings of interviews. As I wondered where I could get something to eat, I heard footsteps coming up the stairs and Bobbie appeared in the doorway, his Marty Feldman hair silhouetted against the light. He walked in and plonked a plate down in front of me, on which sat two foil-wrapped chocolate marshmallows. ‘I’ve got to tell you,’ he said, ‘I’m not much of a cook.’

Maybe not, but he was a very helpful ally in this strange and familiar place. He phoned me recently, asking me to find him a couple of Chasidic Jews to photograph. As though I’d have them around the house. That’s fair enough, though. He’s brought me his people. He can have a pair of mine.

2 THE SETTLERS

Samuel Johnson once told James Boswell that the Giant’s Causeway was worth seeing, but not worth going to see. Early on in my journey I visited it with a guide who was even less enthusiastic. Just before it came into view, he turned to me and said, ‘You’re going to find this place disappointing.’ Luckily I was able to set both verdicts aside, especially the one from the man being paid to promote Northern Ireland. On an early summer’s day, with a stiff breeze blowing, the hexagonal black and gold columns seemed eerie and romantic. The Causeway was a bit smaller than I’d expected, and there were a lot of people around, but it didn’t matter; I was in a good mood, and my expectations had been set very low. Standing on a stone crop, staring out to sea, I was joined by the guide who took me into his confidence. All this, he assured me, wasn’t made by molten rock, forced up through the ground. It couldn’t be. The columns are perfect. They’ve got to be man-made. They must have been built by Stone Age people. Stone Age Irish people.

There is a legend concerning the Giant’s Causeway that it was actually built by Finn McCool (Fionn MacCumhaill in Irish), the leader of a band of great warriors, as a land bridge between Ireland and Scotland. McCool and a Scottish giant had been shouting insults across the sea at each other, but McCool wanted to be able to confront his rival in person. Constructing such a mighty land bridge proved hard work, however, and McCool fell asleep as soon as he had finished. While he slept the Scottish giant thundered down the Causeway towards him, but McCool woke up and spotted him. Perturbed by the size of his opponent, McCool – thinking extremely laterally – built a huge crib and lay down inside it, pretending to be a massive baby. The giant arrived, looked inside the crib, saw this grotesque infant, and panicked. If this was the size of McCool’s baby, how enormous must McCool be? The giant ran back to Scotland, tearing up the Causeway as he went, leaving only the remains that Dr Johnson did not consider worth going to see. Whether it was actually built by Finn McCool, a figure who came to inspire the republican movement, or by Stone Age nationalists laying claim to Irish territory, the Causeway, like so much else in Northern Ireland, has been used to service contemporary claims.

Perhaps the greatest character in Irish mythology is Cuchulainn, the Irish Achilles, who is supposed to have defended Ulster single-handedly against the warriors of Queen Medb of Connaught. Cuchulainn, fearless, earthy, and principled, is a character with whom many have wanted to be associated. Mortally wounded, he is said to have bound himself to a pillar so that he might die standing up, and this scene is recorded on a bronze statue inside Dublin’s General Post Office, erected in memory of the 1916 republican rising. But Cuchulainn is also claimed by unionists and loyalists; a huge mural on the Shankill Estate shows him waving his sword in defiance at those who would threaten Ulster. When I asked a leading unionist politician about the legend of Cuchulainn, he reacted crossly to the word ‘legend’. Cuchulainn’s defence of Ulster is not a legend, he made it clear; it is history.

I found an interesting version of history in a 1982 play, cowritten by Andy Tyrie, then leader of the Ulster Defence Association, a loyalist paramilitary organization. This Is It! is a sharply observed piece of drama that tells the story of a young working-class Protestant who grows disillusioned with unionism’s lack of political ambition. It particularly caught my eye for the views of one of its characters, Sam, who gives an account of Ulster’s early history from a Protestant perspective. Sam argues that the people of Ulster, Protestant and Catholic alike, share a common ancestry that predates the coming of the Celts in the centuries before Christ; in those days, Sam claims, Ulster and Scotland were populated by the same race, called the Picts in Scotland and the Cruthin in Ulster. When the Celts invaded Ulster, they carried out a long and cruel extermination, forcing the Cruthin to move to Scotland. So, says Sam, ‘You could even suppose that some of those who came over here for the Plantation [Ulster’s colonization by English and Scottish Protestants four centuries ago] were in effect coming home again.’ This reading of history allows Sam to argue that Ulster is the Protestant homeland: ‘Our roots are here! Ulster people – Catholic and Protestant – both have a common ancestry and a common right to be here.’

Fascinated by this, I spoke to a respected university professor who prefers not to be named. Evidently the subject is rather controversial. The professor told me that the pre-Christian period of Irish history is very dark. The Picts were present in parts of Scotland, and there is indeed a tradition of a Cruthin people in East Ulster. But while these people might well have communicated with each other across the sea, and there may even have been an exchange of population, it is impossible to say that the Picts and the Cruthin were the same race. With regard to the Celts, the professor says that although there is a tradition that they arrived in Ireland in the years just before the birth of Christ, no archaeological evidence exists for a mass arrival or for an invasion, and there is no evidence at all that they carried out a long and cruel extermination of indigenous people. There is a tradition of a migration of people from Ireland to western Scotland at the time of the Roman invasion of Britain, but it is no more than a tradition. So far as the idea of settlers ‘coming home’ to Ulster at the time of the plantations is concerned, the professor says that the seventeenth-century Scottish settlers came primarily from Scotland’s border with England. These settlers were not Gaelic speakers, and it would be wrong to consider them the same people as those who may once have left Ulster. It would, the professor says, be very difficult to identify an ‘Ulster people’. I am left with the strong caveat that I should be careful of historical interpretations which carry an underlying political motivation.

‘Throughout history,’ declares Sinn Féin’s website, ‘the island of Ireland has been regarded as a single national unit. Prior to the Norman invasion from England in 1169, the Irish had their own system of law, culture, and language, and their own political and social structures.’ While it makes political sense for Sinn Féin to describe pre-1169 Ireland as a ‘single national unit’, it makes less historical sense. During this period the island was a patchwork of independent chiefdoms, often at war with one another, and ready to make alliances to achieve greater power. One such alliance led to the arrival of the English in Ireland. It was struck between Dermot MacMurrough, deposed King of Leinster, and Henry II, King of England, and its legacy has dominated the story of Ireland for the past eight hundred years. Henry granted MacMurrough the services of Anglo-Norman barons to help him to regain his lost kingship. One of these barons, the Earl of Pembroke, known as ‘Strongbow’, overran Waterford and Dublin, and defeated the High King of Ireland in battle. Fearing the emergence of a rival Norman kingdom across the sea, Henry landed an army at Waterford in 1171, with which to confront the ambitious Earl. Strongbow quickly pledged obedience to Henry and promised him the lands that he had conquered. As Henry proceeded through Ireland, the native Irish kings swore fealty to him in turn – all except the rulers of Ulster.

This story of England’s first intervention in Ireland is told by the Welsh-Norman chronicler Giraldus Cambrensis, who describes a meeting at Armagh called by the Irish clergy ‘concerning the arrival of the foreigners in the island’. The clergy’s opinion was that God was allowing the English to ‘enslave’ the Irish, ‘because it had been formerly been their [the Irish people’s] habit to purchase Englishmen indiscriminately from merchants as well as from robbers and pirates, and to make slaves of them’. As a result they decreed that ‘throughout the island, Englishmen should be freed from the bonds of slavery’. Unfortunately for the churchmen, this decree did not result in an English withdrawal. Giraldus proceeds to declare proudly, ‘Let the envious and thoughtless end their vociferous complaints that the kings of England hold Ireland unlawfully. Let them learn, moreover, that they support their claims by a right of ownership resting on five different counts…’ Three of these counts rest on legends, one being the claim that the kings of Ireland once paid tribute to King Arthur, ‘that famous king of Britain’. The fourth count is that English rule had the authority of the Pope. The fifth is that ‘the princes of Ireland freely bound themselves in submission to Henry II, king of England, by the firm bonds of their pledged word and oath’. And so, from this casual intervention many hundreds of years ago, described by a highly partial observer, Anglo-Irish relations came to assume their familiar antipathy and bloodshed.

A problem for the English kings who came after Henry II, attempting to assert their authority on Ireland, was the tendency of their representatives to assimilate. The lords who were meant to be cementing English rule began instead to adopt Irish customs, language, and laws, and became difficult to distinguish from the existing Irish chieftains. By the end of the fifteenth century the English Crown’s authority covered only a small area around Dublin, known as ‘the Pale’. The area outside of English influence was therefore considered ‘beyond the Pale’, and remained subject to an anarchy of tribal conflict. Henry VIII attempted to re-anglicize the ‘Old English’ lords; he forced them to drop their Irish titles, and he re-granted them their lands under English feudal law, but his authority was not noticeably strengthened as a result. Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, faced six rebellions from the Old English and the Irish. She put these down ruthlessly, and appointed officials with little sympathy for the local people. One of these officials was the poet Edmund Spenser, author of the tender couplet ‘Such is the power of love in gentle mind, that it can alter all the course of kind.’ But Spenser’s gentle mind did not extend to the Irish people, whom he considered ‘vile catiff wretches, ragged, rude, deformed’. As England became wealthier and more powerful, Ireland became a country to be suppressed and civilized. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign a centralized English administration was in place, as was a bitterly confirmed resentment of English rule.

By this time the issue of religion had also emerged. The Reformation of the Church had taken hold in England, but it had failed to do so in Ireland. It was proving difficult enough to impose an English administration on a resistant, widely scattered population, and utterly impossible to impose the Protestant religion. So a new policy was adopted: the colonization of the province by loyal Protestants. In 1606 Sir John Davies, the Irish attorney general, described Ulster as ‘the most rude and unreformed part of Ireland’ and he hoped that ‘that the next generation will in tongue and heart and every way else become English’. What better way to achieve this, and to deter the French and Spanish from creating an Irish bridgehead from which to invade England, than by settling Ulster with English and Scottish Protestants? A good part of the existing Irish population was forced from its land by these ‘plantations’, and the repercussions have been felt down the centuries. The Northern Ireland government of much of the twentieth century would be run by, and for, the descendants of Protestants who were brought to the province in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Lessons learnt in Ulster were immediately put to use by the English in their next effort at colonization by plantation, across the Atlantic in Virginia and New England. The Ulster plantation was the forerunner of the foundation of America. In the New World the native population was all but extinguished by slaughter and Old World diseases, leaving the settlers to thrive and give thanks every November. In Ulster, where the natives did not die off, a population with split allegiances and long memories was created.

Early in my travels I met a man named John Beresford-Ash. He lives just outside Derry with his beautiful French wife, Agnès, in a lovely late-seventeenth-century house, Ashbrook, that benefits from looking and feeling its age. John is a wonderfully old-fashioned character, impeccably mannered, entertaining, honest, and indiscreet. His family can be traced back over four centuries to the earliest Protestants to arrive in Ulster, and I had been told that he would be an interesting man to speak to, so I telephoned him and was immediately invited to lunch the following day. I showed up and sat with John and Agnès, intending to interview him after the meal, but the food was good, the wine kept coming, and the conversation bubbled along, taking in subjects as various as Lord Lucan (an old friend of John’s who is indisputably dead) and the Nuremberg Trials (another old friend was the junior British counsel). I finally rolled out of Ashbrook, virtually incapable, with the promise of an interview the following day. The promise was warmly kept.

Ashbrook was originally granted to Beresford-Ash’s ancestor, General Thomas Ash, by Elizabeth I in recognition of his loyal service to the Crown. Another ancestor was Tristram Beresford, the first land agent for the merchants of the City of London. Beresford was evidently a pragmatist. According to his descendant: ‘The Spanish were very short of oak trees to build their warships and one day some Spanish galleons turned up in the River Foyle. There were a lot of lovely oak trees here in Derry, doire being the Irish for oak grove, and though Elizabeth was a marvellous queen, she was awfully tight-fisted and she hadn’t paid her troops. My ancestor practically had a mutiny on his hands because his troops hadn’t been paid, and the Spanish had an awful lot of gold, so he said to the Spaniards, “If you can pay, I will give you the oak trees of Derry,” which he did – and thus committed high treason. He was had up by the court of the Star Chamber, but fortunately for him – and indeed most fortunately for me – he was a great friend of Walter Raleigh, who interceded on his behalf, so he didn’t get his neck stretched.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.