Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

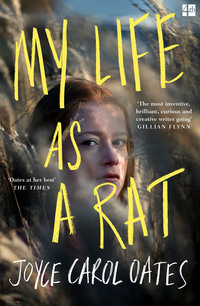

Kitabı oku: «My Life as a Rat», sayfa 5

The thought of being kept home with my mother and my brothers day after day panicked me. Trapped in the house where everyone was waiting for—what? What would save them? For someone else to be arrested for the crime?

As Mom said, “Whoever did this terrible thing. The guilty people.”

There was the hope, too, that the evidence police were assembling was only circumstantial, not enough to present to a grand jury. Especially, a jury comprised of white people. This was what the boys’ lawyers insisted.

Relatives, neighbors, friends of Daddy’s dropped by our house to show support. Fellow Vietnam veterans. At least, this was the pretext for their visit.

A call came from Tommy Kerrigan’s office, for Daddy. Not clear whether Tommy Kerrigan himself spoke to Daddy or one of his assistants.

Sometimes Mom refused to see visitors but hid away upstairs when the doorbell rang and told us not to answer it. At other times she was excited, insisting that visitors stay for meals. Female relatives helped in the kitchen. Beer, ale was consumed. There was an air of festivity. The subject of all conversation was the boys—how badly they were being treated by the police, how unfair, unjust the investigation was.

Because they are WHITE. No other reason!

The name “Hadrian Johnson” was never uttered. There was reference to the “black boy.” That was all.

Jerr and Lionel didn’t speak of Hadrian at all. It was as if the South Niagara police were to blame for their troubles, or rather the chief of police, who’d been an appointment of Tommy Kerrigan’s when Tommy Kerrigan had been mayor of South Niagara—Rat bastard. You’d think he’d be more grateful.

There may have been friends, relatives, acquaintances who believed that Jerr and Lionel were guilty of what they’d been accused of doing but these people did not visit us. Or if they did, they were circumspect in their emotional support for beleaguered Lula and Jerome.

Terrible thing. Such a tragedy. Try to hope for the best …

There was much speculation on the identity of the “anonymous witness” who’d provided the first several letters of the Chevrolet license plate. How could police be certain that he was telling the truth? Wasn’t it possible he’d deliberately misinformed them? Giving them the first few digits of Jerr’s car, to implicate Jerome Kerrigan’s son? And daring to specify Hadrian Johnson’s assailants as “white boys.”

(In the dark, how could a witness be so certain of the color of the boys’ skin? He couldn’t have had more than a glimpse of the boys at the side of the road. By his own account he’d slowed down for only a few seconds then sped up and drove away.)

(Very possibly, this “anonymous witness” was a black man himself. Involved in the beating himself …)

The phone rang repeatedly. Often Mom stood a few feet away squinting at it. She was fearful of answering blindly—not since Liza Deaver did she dare pick up a receiver without knowing exactly who was calling. If I was nearby she asked me to answer for her as she stood transfixed while I lifted the receiver and said Sorry nobody is here right now to speak with you. Please do not call again thank you!—quickly hanging up before the voice on the other end could express surprise or scold me.

One day I was alone in the kitchen after school. Staring at the phone as it began to ring. And there was Lionel beside me. Looming over me. “Don’t answer that,” he said. He spoke tersely, tightly as a knot might speak. Giving me no time to react, to move away from the phone, but rudely knocking me aside though I’d made no move to answer it.

Lionel’s mouth was twisted into a slash of a smile. He’d stayed home from school, he’d barely spoken to anyone in the family for days except our father and only then in private. Much of the time he was playing video games in his room. The cut beneath his eye had not healed, he must have been picking at the scab. His jaws were unshaven. The neck of his T-shirt was stretched, and soiled. I smelled something sharp, rank as an animal’s smell lifting from him. I laughed nervously, edging away.

Lionel said, in a jeering singsong voice: “Hey there, ‘Vi-let Rue’! Where’re you going, you!”

I eased away. I fled.

Wanting to assure my angry brother—I won’t tell Dad. Or anyone. I told you—I promised.

The Siege

WITHOUT REGAINING CONSCIOUSNESS, HADRIAN JOHNSON died in the hospital on November 11.

NOW THE KERRIGAN HOUSEHOLD WAS TRULY UNDER SIEGE. LIKE A boat, buffeted by ferocious winds.

We Kerrigans huddled inside, clutching at one another. Daddy would protect us, we knew.

Jerr returned to work, where his employer and most of his fellow workers were inclined to be sympathetic toward him. Lionel was suspended indefinitely from school.

Fewer people dropped by the house. But Kerrigan relatives were loyal. Staying late into the night in the basement room Daddy had remodeled into a TV room, drinking, talking loudly, vehemently.

Just adults in the basement with Daddy. No kids including Jerr and Lionel.

With so many people in the house it wasn’t hard for me to avoid my brothers. At meals they ignored me, as they ignored their younger brothers and sisters, sitting next to Daddy, eating with their heads lowered and addressing one another in terse exchanges. Their lawyer’s last name was O’Hagan—you could hear their remarks peppered with these syllables—O’Hagan—but not what they were saying.

Since he’d shoved me in the kitchen Lionel rarely looked in my direction. I had come to think that he’d forgotten me, for he had much else to think about. Jerr’s pebble-colored eyes drifted over me, restless, brooding. Within a week or so my oldest brother had lost weight, his face was gaunt, his manner edgy, distracted. While Lionel ate hungrily Jerr pushed food about on his plate and preferred to drink beer from a can. Often he lifted the can so carelessly to his mouth, rivulets of liquid ran glistening down his chin. One evening Daddy told him no more, he’d had enough, and Jerr rose indignantly from the table unsteady on his feet murmuring what sounded like Fuck.

Or maybe, judging from Daddy’s reaction—Fuck you.

In an instant Daddy was on his feet too. Gripping Jerr by the scruff of the neck and shaking him as you might shake an annoying dog. Shoving him back against the wall so that the breath was knocked out of him. Glasses, silverware fell from the table onto the floor. There were cries of alarm, screams. Jerr scrambled to his feet ashen-faced but knew better than to protest.

No one dared leave the table except Jerr who retreated like a kicked dog. Daddy was flush-faced, furious. We sat very still waiting for the fury to pass.

In silence we finished the meal. In silence, my sisters and I cleared the table for our mother who was trembling badly. It was frightening and yet thrilling, to witness our father so swiftly disciplining one of us who had disrespected him.

That is the sick, melancholy secret of the family—you shrink in terror from a parent’s blows and yet, if you are not the object of the blows, you swell with a kind of debased pride.

My brother, and not me. Him, therefore not me.

OUR MOTHER BEGAN TO SAY, MANY TIMES IN THOSE WEEKS—Those people are killing us.

On the phone she complained in a faltering, hurt voice. To her children, who had no choice but to listen. She’d been talking to our parish priest Father Greavy who’d confirmed her suspicion, she reported back to us, that those people were our enemies

We wondered who those people were. Police? African Americans? Newspaper and TV reporters who never failed to mention that an anonymous witness had described “white boys” at the scene of the beating—“as yet unidentified.”

Those people could be other white people of course. Traitors to their race who defended blacks just for the sake of defending blacks. Hippie-types, social-worker types, politicians making speeches to stir trouble for the sake of votes.

Taking the side of blacks. Automatically. You can hear it in their voices on TV …

No one in our family had any idea that I knew about what had happened that night. What might have happened.

That I knew about the bat. That there was a bat.

In articles about the beating there seemed to be no mention made of a “murder weapon”—so far as most people might surmise there wasn’t one. (Had police actually mentioned a tire iron? I had not heard this from anyone except my mother reporting one of many rumors.) A boy had been beaten savagely, his skull (somehow) fractured. That was all.

I wondered if Jerr and Lionel talked about me. Our secret.

They knew only that I knew they’d been fighting that night. They had no reason to suspect that I knew about the bat. Surely they thought that I believed their story of having been in Niagara Falls and not in South Niagara.

She wouldn’t tell. Not Vi’let Rue.

You sure? She’s just a kid.

Anyway, what does she know? None of them know shit.

Because …

BECAUSE THEY COULD NOT HAVE DONE THAT, SUCH A TERRIBLE thing there came to be They did not do that terrible thing.

Because It can’t be possible there came to be It is not possible. Was not possible.

Because They wouldn’t lie to us there came to be They did not lie to us. Our sons.

Through the floorboards you heard. Through the furnace vent you heard. Amid the rattling of the ventilator. Through shut doors you heard, and through those walls in the house that for some reason were not so solid as others, stuffed with a cottony sort of insulation that, glimpsed just once, as a wall was being repaired, shocked you looking so like a human lung, upright, vertical.

Like a TV in another room, volume turned low. Daddy’s voice dominant. Mom’s voice much fainter. A pleading voice, a whining voice, a fearful voice, for Daddy hated whining, whiners. Your brothers knew better than to piss and whine. Shouting, cursing one another, shoving one another down the stairs, overturning a table in the hall, sending crockery shattering onto the kitchen floor—such behavior was preferable to despicable whining which Daddy associated with women, girls. Babies.

And so, your mother did not dare speak at length. Whatever she said, or did not say, your father would talk over, his voice restless and careening like a bulldozer out of control. Was he rehearsing with her—You could say they were home early that night. By ten o’clock. You remember because …

They would choose a TV program. Something your brothers might’ve watched. Better yet: sports. Maybe there’d been a football game broadcast that night … On HBO, a boxing match.

Jerome I don’t think that I—don’t think that I can …

Look. They aren’t lying to us—I’m sure. But it might look like they are lying, to other people. Sons of bitches in this town they’d like nothing better than to fuck up decent white kids.

Don’t make me, Jerome … I don’t think that I, I can …

You can! God damn it, they might’ve been home—might’ve watched the fucking TV. Or you might remember it that way and even if you were wrong it could help them.

None of this you heard. None of this you remember.

The Rescue

BY CHANCE YOU SAW.

So much had become chance in your life.

Headlights turning into the driveway, in the dark. Your father’s car braking in front of the garage.

By chance you were walking in the upstairs hall. Cast your eyes down, through the filmy curtains seeing the car turn in from the street. Already it was late. He’d missed supper. Past 9:00 P.M. No one asked any longer—Where’s Daddy?

In the hall beside the window you paused. Your heart was not yet beating unpleasantly hard. You were (merely) waiting for the car lights to be switched off below. Waiting for the motor to be switched off. Waiting for the familiar sound of a car door slammed shut which would mean that your father had gotten out of the car and was approaching the house to enter by the rear door to signal Nothing has changed. We are as we were.

But this did not seem to be happening. Your father remained in the (darkened) car.

Still the motor was running. Pale smoke lifted from the tailpipe. You were beginning to smell the exhaust, and to feel faintly nauseated.

In the hall by the window you stood. Staring down at the driveway, the idling car. Waiting.

He is not running carbon monoxide into the car. The car is not inside the garage, there is no danger that he will poison himself.

Yet, gray smoke continued to lift from the rear of the car. Stink of exhaust borne on the cold wet air like ash.

He is sitting in the car. He is smoking in the car.

Waiting to get sober. Inside the car.

That is where he is: in the car.

He is safe. No one can harm him. You can see—he is in the car.

You could not actually see your father from where you stood. But there was no doubt in your mind, he was in the car.

Had Daddy been drinking, was that why he was late returning home, you would not inquire. Each time Daddy entered the house in the evening unsteady on his feet, frowning, his handsome face coarse and flushed, you would want to think it was the first time and it was a surprise and unexpected. You would not want to think—Please no. Not again.

You would want to retreat quickly before his gaze was flung out, like a grappling hook, to hook his favorite daughter Vi’let Rue.

It was one of those days in the aftermath of the death of Hadrian Johnson when nothing seemed to have happened. And yet—always there was the expectation that something will happen.

Your brothers had not been summoned, with O’Hagan, to police headquarters that day. So far as anyone knew, the others—Walt, Don—had not been summoned either.

No arrests had (yet) been made but your brothers were captive animals. Everyone in the Kerrigan house was a captive animal.

They’d ceased reading the South Niagara Union Journal. Someone, might’ve been Daddy, tossed the paper quickly away into the recycling bin as soon as it arrived in the early morning,

For articles about the savage beating, murder of Hadrian Johnson continued to appear on the front page. The photograph of Hadrian Johnson continued to appear. Gat-toothed black boy smiling and gazing upward as if searching for a friendly face.

You saw the newspaper, in secret. Not each day but some days.

These people are killing us. Possibly, your mother meant the newspaper people. The TV people.

You are beginning to feel uneasy, at the window. You are beginning to wonder if indeed your father is actually in the car. And it is wrong of you to spy upon your father as it is wrong to spy upon your mother. Faces sagging like wetted tissue when they believe that no one is watching. Oh, you love them!

In the car Daddy is (probably) smoking. Maybe he brought a can of ale with him from the tavern. Maybe a bottle.

The bottles are more serious than the cans. The bottles—whiskey, bourbon—are more recent than the cans.

In the plastic recycling bin, glass bottles chiming against one another.

Daddy is not supposed to smoke. Daddy has been warned.

A spot on his lung two years before but a benign spot. High blood pressure.

More than once Daddy has declared that he has quit smoking—for the final time.

When Daddy smokes he coughs badly. In the early morning you are wakened hearing him. So painful, lacerating as if someone is scraping a knife against the inside of his throat.

Years ago when you were a little girl Daddy would come bounding into the house—Hey! I’m home.

Calling for you—Hey Vi’let Rue! Daddy is home.

Where’s Daddy’s best girl? Vi’let RUE!

That happy time. You might have thought it would last forever. Like a TV cartoon now, exaggerated and unbelievable.

Now Daddy is showing no inclination to come into the house. (Maybe he has fallen asleep, behind the wheel? A bottle in his hand, that is beginning to tip over and spill its contents …) He has turned off the motor, at least. You are relieved, the poison-pale smoke has ceased to lift from the tailpipe.

He’s coming inside now. Soon.

There is a meal for Daddy, in the oven. Covered in aluminum foil.

Even when your mother must know that Daddy won’t be eating the supper she has prepared for him there is a meal in the oven which, next day, midday when no one is around, Mom will devour alone in the kitchen rarely troubling to heat it in the microwave. (You have seen her with a fork picking, picking, picking at the cold coagulated meat, mashed potatoes. You have seen your mother eating without appetite, swiftly picking at tasteless food.)

It is unnerving to you, the possibility that no one is in the car.

In the driveway, in the dark. Dim reflected light from a streetlight in the wet pavement.

No, there’s no one there!

Somehow, your father has slipped past you. You have failed to see him.

Or, your father has slumped over behind the wheel, unconscious. He has found an ingenious way to divert the carbon monoxide into the car while no one noticed …

The father of a classmate at school has died, a few weeks ago. Shocking, but mysterious. What do you say?

You say nothing. Nothing to say. Avoid the girl, not a friend of yours anyway.

As, at school, your friends have begun to avoid you.

Pretending not to notice. Not to care. Hiding in a toilet stall dabbing wetted tissues against your face. Why are your eyelids so red? So swollen?

But now you have begun to be frightened. You wonder if you should seek out your mother. Mom? Daddy is still in the car, he has been out there a long time … But the thought of uttering such words, allowing your parents to know that you are spying on them, is not possible.

And then, this happens: you see someone leave the house almost directly below, and cross to the car in the driveway.

Is it—your mother?

She, too, must have been standing at a window, downstairs. She’d seen the headlights turning into the driveway. She’d been waiting, too.

Slipping her arms into the sleeves of someone’s jacket, too large for her. Bare-headed in light-falling snow that melts as soon as it touches the pavement, and her hair.

It is brave of Mom to be approaching Daddy, you think. You hold your breath wondering what will happen.

For you, your sisters, and your brothers have seen, numerous times, your father throwing off your mother’s hand, if she touches him in a way that is insulting or annoying to him. You have seen your father stare at your mother with such hatred, your instinct is to run away in terror.

In terror that that face of wrath will be turned onto you.

You are watching anxiously as, at the car, on the farther side of the car where you can’t see her clearly, your mother stoops to open the door. Tugging at the door, unassisted by anyone inside.

And now, what is your mother doing? Helping your father out of the car?

You have never seen your mother helping your father in any way, like this. You are certain.

At first, it isn’t clear that Daddy is getting out of the car. That Daddy is able to get out of the car.

It has become late, on Black Rock Street. A working-class neighborhood in which houses begin to darken by 10:00 P.M.

In early winter, houses begin to lighten before dawn.

Up and down the street, in winter, when the sun is slow to appear, windows of kitchens are warmly lit in the hour before dawn. You will remember this, in your exile.

Well—Daddy is on his feet, in the driveway. He has climbed out of the car with Mom’s assistance, and he does not appear to be angry at her. His shoulders are slumped, his legs move leadenly. The lightness in his body you remember from a time when you were a little girl, the rough joy with which he’d danced about in the garage, teaching your brothers to box, has passed from him. His youth has passed from him. The years of his young fatherhood when his sons and daughters had been beautiful to him, when he’d stared at them with love and felt a fatherly pride in them, have passed.

Transfixed at the window you watch. For the danger is not past yet.

You steel yourself: your father will fling your mother from him with a sweep of his arm, he will curse her …

But no, astonishingly that doesn’t seem to be happening. Instead, your father has allowed your mother to slip her arm around his waist. He steadies himself against her, leaning heavily on her.

Awkwardly, cautiously they make their way toward the house. Taking care not to slip on the driveway where ice is beginning to form, thin as a membrane.

What words have they exchanged? What has your mother said to your father, that has blunted his rage?

You have drawn away from the window. You have let the curtain fall back into place. You do not want either of your parents to glance up, to see you at the window, watching.

It is a remarkable fact, your father leaning heavily upon your mother, who is several inches shorter than he, and must weigh seventy pounds less than he does. Yet she holds him up without staggering, your mother is stronger than you would have imagined.

Together your parents approach the house, walking cautiously, like much older people, in this way you’ve never seen. They pass out of your sight, below. You stand very still waiting for them to enter the house, waiting to hear the door open below, and close, so you can think, calmly—They are both safe now. For now.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.