Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

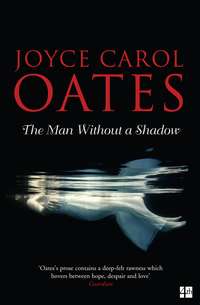

Kitabı oku: «The Man Without a Shadow», sayfa 3

But he doesn’t look, he has not (yet) seen the drowned girl. He was not there, so he cannot see. He cannot remember what he has not seen.

On the plank bridge in this strange place so many years later he does not turn his head. He does not glance around. He grips the railing tight in both his hands, bravely he steels himself against the anticipated wind.

CHAPTER TWO

Mr. Hoopes? Eli?”

“Hel-lo!”

“My name is Margot Sharpe. I’m Professor Ferris’s associate. We’ve met before. We’ve come to take up a little of your time this morning …”

“Yes! Wel-come.”

Light coming up in his eyes. That leap of hope in his eyes.

“Wel-come, Margot!”

Her hand gripped in his, a clasp of recognition.

He does remember me. Not consciously—but he remembers.

She can’t write about this, yet. She has no scientific proof, yet.

The amnesiac will discover ways of “remembering.” It is a non-declarative memory, it bypasses the conscious mind altogether.

For there is emotional memory, as there is declarative memory.

There is a memory deep-embedded in the body—a memory generated by passion.

Suffused with happiness, Margot Sharpe feels like a balloon rapidly, giddily filling with helium.

“MR. HOOPES? ELI?”

“Hel-lo! Hel-lo.”

He has not ever seen her before. Eagerly he smiles at her, leans close to her, to shake her hand.

In his large, strong hand, Margot Sharpe’s small hand.

“You may not recall, we’ve met before—‘Margot Sharpe.’ I’m one of Professor Ferris’s research associates. We’ve been working together for—well, some time.”

“‘Mar-got Sharpe.’ Yes. We’ve been working together for—some time.” E.H. smiles gallantly as if he knows very well how long they’ve been working together, but it is a secret between them.

Today E.H. has the larger of his sketchbooks with him. He has finished the New York Times crossword puzzle—the newspaper page is discarded as usual, on the floor.

E.H. has been sketching with a stick of charcoal, seated beside a window in the anterior of the fourth-floor testing-room. He appears to be oblivious of the plate glass window that is dramatically lashed with rain, as he is oblivious of his clinical surroundings; the objects of E.H.’s art, which excite his fierce attention, are almost exclusively interior, and he does not care to share them with others.

(Except sometimes, Margot Sharpe.)

(Though Margot knows not to ask E.H. to see his drawings but to wait for E.H. to offer to show her. The offer, if it comes, will come spontaneously.)

“Do you have any idea how long we’ve been working together, Eli?”—Margot always asks.

E.H.’s smile wavers. He speaks thoughtfully, gravely.

“Well—I think—maybe—six weeks.”

“Six weeks?”

“Maybe more, or maybe less. You know, I have some problem with what is called ‘memory.’”

“How long have you had this problem, Eli?”

“How long have I had this problem? Well—I think—maybe—six weeks.” E.H. smiles at Margot, with a pleading expression. He is still gripping Margot’s hand; gently, she has to detach it.

“Do you know what has caused this problem, Eli?”

“Well, it’s ‘neurological.’ I suppose they’ve done X-rays. I think I remember my head shaved. My skull was fractured in Birmingham, Alabama—no one knew at the time. A ‘hairline’ fracture. But then, at the lake back in July, a few months ago, there was a fire. I think that’s what they told me—a fire. Hard to believe that I was careless leaving burning embers in the fireplace but—something happened.” E.H. pauses, frowning like one who is struggling to pull up, from the depths of a well, something unwieldy, very heavy that is straining every muscle in his body. “A fire, that burnt up my damned brain.”

“A fever, maybe?”

“A fever is a fire. In the damned brain.”

It is a wet windy overcast morning in March 1969.

SHE THINKS, HIS name has been eerily prescient—Hoopes.

For Elihu Hoopes has lived, for the past four and a half years, in an indefinable present-tense. A kind of time-hoop, a Möbius strip that turns upon itself, to infinity.

Except “infinity” is less than seventy seconds.

There is no was in Elihu Hoopes’s life, there is only is.

Forever he will be thirty-seven years old. Forever, he will be confused about where he is, and what has happened to him.

A fire? I think it was a fire. Or, Granddaddy’s two-passenger single-prop plane crash-landed on the island, and burst into flames. And later in the hospital, I think there was a fire, too. My clothes and hair were wet, but smoldering. I could smell my hair singed. I may have breathed in some of the fire, and burnt my lungs.

They said that I had a high fever but—it was a fire, I could see and smell.

The girl was not found. There were rescue parties searching for her. In the woods around Lake George. On the islands.

If someone had taken her, it was believed he might’ve taken her to one of the islands. If he had a boat. If no one saw.

In his little, light Beechcraft aircraft painted bright chrome yellow like a giant bird Granddaddy flew above the lake. Many times Granddaddy flew above the lake, you would hear the prop-plane engine passing low over the roof of the house.

Granddaddy said, Come with me, Eli! We will search together for your lost cousin.

Not the first time the little boy had flown in the plane with his grandfather but it would be the last.

IN HIS BRIGHT affable voice E.H. begins to read from his notebook.

“‘There is no journey, and there is no path. There is no wisdom, there is emptiness. There is no emptiness.’”

Pausing to add, “This is the wisdom of the Buddha. But there is no wisdom, and there is no Buddha.”

He laughs, sadly.

“There is no test, and there is no ‘testes.’”

And he laughs again. Sadly.

SHE HAS BEEN instructed: to discover, you have to destroy.

To locate the source of behavior in the brain, you have to destroy much of the brain.

Monkey-, cat-and rat-brains. In search of elusive and mysterious memory. Years, decades, thousands of animal-brains, hundreds of thousands of hours of surgery. Systematically, methodically. Meticulous lab records. Unyielding cruelty of the research scientist to whom no (living) specimen is an end in itself but a (possible) means to a greater end. Hundreds of thousands of animals sacrificed in the pursuit of the “engram”—the brain’s ostensible record of memory.

A principle of experimental neuroscience.

No one can surgically explore a (living, normal) human brain, only just animal-brains. And all these decades, results have been inconclusive. Margot Sharpe notes in her amnesia logbook the (famous/infamous) conclusion of the great experimental psychologist Karl Lashley:

This series of experiments has yielded a good bit of information about what and where the memory trace is not. I sometimes feel … the necessary conclusion is that (memory) is just not possible.

THE CHASTE DAUGHTER. How lucky Margot Sharpe has been! And she wants to think—My career—my life—lies all before me.

By 1969 the phenomenon of the amnesiac “E.H.” is beginning to be known in scientific circles.

An extraordinary case of total anterograde amnesia! And the subject otherwise in good health, intelligent, cooperative, sane—a rarity in brain pathology research where living patients are likely to be psychotic, moribund, or brain-rotted alcoholics.

Articles by Milton Ferris of the University Neurological Institute at Darven Park on “E.H.” have begun to appear in the most prestigious neuroscience journals; usually these articles list Ferris’s research associates as co-authors, and Margot Sharpe is among them. Seeing her name in print, in such company, has been deeply gratifying to Margot, and it has happened with surprising swiftness.

Rich with data, graphs, statistics, and citations, the articles bear such titles as “Losses in Recent Memory Following Infectious Encephalitis”—“Retention of ‘Declarative’ and ‘Non-declarative’ Memory in Amnesia: A History of ‘E.H.’”—“Short-Term Retention of Verbal, Visual, Auditory and Olfactory Items in Amnesia”—“Encoding, Storing, and Retrieval of Information in Anterograde Amnesia.” Their preparation is a lengthy, collaborative effort of months, or even years, with Milton Ferris overseeing the process. No paper can be submitted to any journal, of course, without Ferris’s imprimatur, no matter who has actually designed and executed the experiments, and who has done most of the research and writing. Recently, Margot has been given permission by Ferris to design experiments of her own involving sensory modality, and the possibility of “non-declarative” learning and memory. In the prestigious Journal of American Experimental Psychology a paper will soon appear with just the names of Milton Ferris and Margot Sharpe as authors; this is a forty-page extract from Margot’s dissertation titled “Short-Term and Consolidated Memory in Retrograde and Anterograde Amnesia: A Brief History of ‘E.H.’” It is, Milton Ferris has told Margot, the most ambitious and thoroughly researched paper of its kind he has ever received from a female graduate student—“Or any female colleague, for that matter.”

(Ferris’s praise is sincere. No irony is intended. It is 1969—it is not an age of gender irony in scientific circles, where few women, and virtually no feminists, have penetrated. To her shame, Margot has been thrilled to hear Milton Ferris spread the word of her to his colleagues, who’ve made a show of being impressed. Margot doesn’t want to think that her mentor’s praise is somewhat mitigated by the fact that there are only two women professors in the Psychology Department at the university, both “social psychologists” whom the experimental psychologists and neuroscientists treat with barely concealed scorn.)

That the lengthy article has been accepted so relatively quickly after Margot submitted it to the Journal of American Experimental Psychology must have something to do with Ferris’s intervention, Margot thinks. It has not escaped her notice that one of the editors of the journal is a protégé of Ferris of the late 1940s; Ferris himself is listed among numerous names on the masthead, as an “advisory editor.”

In any case, she has thanked Ferris.

She has thanked Ferris more than once.

Margot is conscious of her very, very good luck. Margot is anxious to sustain this luck.

It isn’t enough to be brilliant, if you are a woman. You must be demonstrably more brilliant than your male rivals—your “brilliance” is your masculine attribute. And so, to balance this, you must be suitably feminine—which isn’t to say emotionally unstable, volatile, “soft” in any way, only just quiet, watchful, quick to absorb information, nonoppositional, self-effacing.

Margot thinks—It is not difficult to be self-effacing, if you have a face at which no one looks.

“HEL-LO!”

“Hello, Mr. Hoopes—‘Eli.’ How are you?”

“Very good, thanks. How are you?”

In the vicinity of E.H. you feel the gravitational tug of the present tense.

In the vicinity of E.H., you glance about anxiously for your own shadow, as if you might have lost it.

Margot is very lonely except—Margot is not lonely when she is with E.H. Others in Ferris’s lab would be astonished to learn that Margot Sharpe who is so stiffly quiet in their presence speaks impulsively at times to the amnesiac subject E.H.; she has confided in him, as to a close and trusted friend, when they are alone together and no one else can hear.

She has volunteered to take E.H. for walks in the parkland behind the Institute. She has volunteered to take E.H. downstairs to the first-floor cafeteria, for lunch. If E.H. is scheduled for medical tests she volunteers to take him.

She is cheerful in E.H.’s company, as E.H. is cheerful in hers. She has boasted to E.H. of her academic successes, as one might boast to an older relative, a father perhaps. (Though Margot doesn’t think of Elihu Hoopes as fatherly: she is too much attracted to him as a man.) She has admitted to him that she is, at times, very lonely here in eastern Pennsylvania, where she knows no one—“Except you, Eli. You are my only friend.” E.H. smiles at this revelation as if their exchange was a part of a test and he is expected to speak on cue: “Yes—‘my only friend.’ You are, too.”

Margot knows that E.H. lives with an aunt, and assumes that he must see family members from time to time. She knows that his engagement was broken off a few months after E.H.’s recovery from surgery, and that his fiancée never visits him. What of his other friends? Have they all abandoned him? Has E.H. abandoned them? The impaired subject will wish to retreat, to avoid situations that exacerbate stress and anxiety; E.H. is safest and most secure at the Institute perhaps, where he can’t fail to be, almost continuously, the center of attention.

Margot thinks how for the amnesiac subject, are not all exchanges part of a test? Is not life itself a vast, continuous test?

It isn’t clear during their intimate exchanges if E.H. remembers Margot’s name—(frequently, he confuses her with his childhood classmate)—but unmistakably, he remembers her.

He understands that she is a person of some authority: a “doctor” or a “scientist.” He respects her, and relates to her in a way he doesn’t relate to the nursing staff, so far as Margot has observed.

Of course, you can say anything to E.H. He will be certain to forget it within seventy seconds.

And how difficult this is to comprehend, even for the “scientist”: what Margot has confided in E.H. is inextricably part of her memory of him, but it is not part of his memory of her.

Margot confides in E.H.: her imagination is so aflame she has trouble sleeping through the night. She wakes every two or three hours, excited and anxious. New ideas! New ideas for tests! New theories about the human brain!

She tells E.H. how badly she wants to please Milton Ferris; how fearful she is of disappointing the man—(who is frequently disappointed with young colleagues and associates, and has a reputation for running through them, and dismissing them); she wants to think that Ferris’s assessment of her “brain for science” is accurate, and not exaggerated. It’s her fear that Ferris has made her one of his protégées because she is a young woman of extreme docility and subservience to him.

Margot confesses to E.H. how sometimes she falls into bed without removing her clothing—“Without showering. Sleeping in my own smell.”

(So that E.H. is moved to say, “But your smell is very nice, my dear!”)

She confesses how exhausted she makes herself working late at the lab as if in some way unknown to her she disapproves of and dislikes herself—can’t bear herself except as a vessel of work; for she will not be loved if she doesn’t excel, and there is no way for her to excel except by working and pleasing her elders, like Milton Ferris. She recalls from a literature class at the University of Michigan a nightmarish short story in which the body of a condemned man is tattooed with the law he’d broken, which he is supposed to “read”—she doesn’t recall the author’s name but has never forgotten the story.

E.H. says, with an air of affectionate rebuke, “No one forgets Franz Kafka’s ‘In the Penal Colony.’”

He too had read it as an undergraduate—at Amherst.

Margot is surprised, and touched. “You remember it, Eli? That’s—of course, that’s …” It is utterly normal and natural for E.H. to remember a story he’d read years before his illness. Yet, Margot who’d read the story not nearly so long ago, could not recall the title.

E.H. begins to recite: “‘“It’s a peculiar apparatus,” said the Officer to the Traveler, gazing with a certain admiration at the device … It appeared that the Traveler had responded to the invitation of the Commandant only out of politeness, when he’d been invited to witness the execution of a soldier condemned to death for disobeying and insulting his superior … Guilt is always beyond doubt.’”

E.H. laughs, strangely. Margot has no idea why.

Something about the man without a shadow reciting these lines makes her fearful—I don’t want to know. Oh please!—I don’t want to know.

THEY HAVE NEVER told him—Your cousin is dead. Your cousin was dead as soon as she disappeared.

No one saw. No one knows.

Wake up, Eli! Silly Eli, it’s only a dream.

So much Eli has seen that summer, only a dream.

SHE RENTS A single-bedroom unit in dreary university graduate housing, overlooking a rock-filled ravine at the edge of the sprawling campus. (The University Neurological Institute at Darven Park is several miles away in an upscale Philadelphia suburb.) She avoids her neighbors, who seem so much less serious than she, given to playing music loudly, and talking and laughing loudly; especially, she avoids married couples—the thought of marital intimacy, the pettiness of domestic life and sheer waste of time required for such a life, makes her feel faint. She has no time for friends—she has ceased writing to her friends from college; they seem diminished to her now, like pygmies. One or two of the men in Ferris’s lab have—(she thinks, she isn’t absolutely sure)—have made sexual advances to her, awkwardly and obliquely; with similar awkwardness, and much embarrassment, she has discouraged them—No I don’t think so. I—I don’t think—it’s a good idea to see each other outside the lab … Seeing her fellow researchers in such relentless intimacy, day following day, for hours each day, it is not possible for Margot to harbor romantic feelings toward the men, or feelings of friendship for the other women; like rivalrous siblings they are easily irritated by one another, and easily provoked to jealousy, for each is vying with the others continuously—(how fatiguing this is!)—for admiration, approval, affection from Milton Ferris.

Work has become her addiction, as work has become her salvation. In human relations you never know where you stand; in your work you can mark progress clearly, and your progress will be noted by others—your distinguished elders.

It is slightly shameful to Margot, how she lives for Milton Ferris’s praise—Good work, Margot!—a murmur like a caress along the length of her body.

At times she is sure that there is an (implicit, unstated) promise between her and Ferris, like a match not yet struck.

At other times, seeing how Ferris’s interest waxes, wanes, waxes, she is sure of nothing.

He, Ferris, with his wiry white beard, bristling manner and sharp-glinting eyeglasses, his flashes of wit, sarcasm, insight, and frequent brilliance—(all who work with the man are convinced of his genius)—has become a figure of considerable (if forbidden) romance to Margot Sharpe. He is fifty-seven years old, he has become famous in the field of neuropsychology; he has long been a member of the National Academy of Science. He is (said to be) happily married, or in any case stolidly married. Yet—We are special to each other.

Margot feels a sensation of weakness, faintness—when Ferris singles her out for praise in the lab. Her face flushes with blood, her heart beats with great happiness. It has often been so, for Margot has been, through her life, the exemplary good-girl student: the Daughter.

She is the Chaste Daughter. She is the one who, if you believe in her, will never betray you.

Yet Margot thinks—I am not in love with Milton Ferris.

Then—I must never allow him to know.

In the night in her bed. In this strange darkness, in her bed. Sometimes she slides her arm around her waist, in mimicry of an embrace. Sometimes she caresses her ribs through her skin, taking a kind of mournful pleasure in so intimate (and unthreatening) a touch. Shuts her eyes tight to summon sleep. And there is Elihu Hoopes standing before her with his eager, hopeful smile and stricken eyes—Margot? Hel-lo.

E.H. says—Margot? I am so lonely.

(IN LIFE, MARGOT knows that E.H. will never say these words. For E.H. will never remember Margot from one encounter to another.)

“He is our ‘amnesiac’—his identity must be kept absolutely confidential.”

Milton Ferris speaks lightly—there is something meant to be playful about the words our amnesiac—but of course he is utterly serious. Everyone at the Institute who comes into contact with Elihu Hoopes, who knows his identity, is sworn to secrecy; others are not told his name—“For legal reasons.”

Since Ferris has begun to publish his “exciting” and “controversial” research on E.H., scientists at other universities have contacted him with requests for interviews with the amnesiac subject. Ferris has refused most of these requests as impractical, since, as he says, he and his researchers are currently studying E.H., and it is not possible to subject E.H. to further testing.

“He is our subject, exclusively. That is the agreement.”

Milton Ferris has become vehement on the subject. Exclusively is an unmistakable claim.

PROFESSOR SHARPE, DID you ever consider at any time that you and your fellow researchers were exploiting the individual known in scientific literature as “E.H.”?

No. I did not.

Really? At no time, Professor Sharpe, during the thirty-one years you studied him, did it occur to you that you might be behaving unethically, in exploiting his handicap? His “amnesia”?

I said no. I did not.

And do you speak for your fellow researchers, as well? Do you speak for the neuroscientific community?

I speak for myself. The others can speak for themselves.

But “E.H.” could not speak for himself—could he? Did “E.H.” ever comprehend the nature of his affliction?

I’ve told you, I speak for myself. That is all.

“That is all”—Professor Sharpe? After thirty-one years?

HE IS NOT being exploited, he is being protected from exploitation!

Margot Sharpe wants to protest. In time, Margot Sharpe will protest publicly.

For E.H. is a neurological wonder, capable of odd, unpredictable feats of memory while incapable of remembering “familiar” faces or what he has just eaten for lunch, or whether he has eaten at all. He has astonished observers by interrupting a rote-memory test to recite the names of his grade school classmates at Gladwyne Elementary School in 1935, desk by desk. On other occasions E.H. has recited Major League Baseball statistics, dialogue from favored comic strips Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, Little Orphan Annie, and song lyrics of Oscar Hammerstein. He can recite passages from speeches by Lincoln, Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr. By heart he knows the entirety of the American Declaration of Independence and portions of John Locke’s The Rights of Man. He knows passages from Thoreau’s Walden, Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Jean Toomer’s Cane. On the Institute court he plays tennis with zest and cunning; he can play piano by “sight” reading—some classics, some American popular songs, and Czerny exercises to grade eight. He is remarkably gifted at jigsaw puzzles, crossword puzzles, plastic puzzles of the kind that fit in the palm of the hand and involve moving numbered squares about in a specific pattern. (How Margot hates those damned plastic puzzles!—she’d never been able to do these with the skill of her brothers, whose grades in school were always inferior to hers; when E.H. offers his puzzle for her to try she pushes it away.) If journalists hear of E.H., Margot can imagine sensational TV coverage, articles in People, Time, and Newsweek, the Philadelphia Inquirer and other local publications. Neighbors, acquaintances, medical workers and researchers who know E.H. would be plied with interview requests. Fortunately the Hoopes family isn’t in need of money, so there is little likelihood of E.H. being exploited by his own relatives.

Margot thinks—I vow, I will protect Elihu Hoopes from exploitation.

“‘Elihu Hoopes.’”

These syllables, he hears murmured aloud. The sounds seem to come out of the air about his head.

The strangeness of the proposition—(he cannot think it is a fact)—that these syllables, these sounds, four stresses, constitute a “name”—and the name is “his.”

His body, his brain. His name. Yet, where is he?

It is a peculiar way of speaking, he’d thought long ago as a child—before the fever burnt up his brain. Why would anyone say—I am Elihu Hoopes.

Again he hears the syllables, in a hoarse, slightly derisive voice.

“‘Elihu Hoopes’—who was.”

IS HE AT Lake George? But where? Not on one of the islands, which have no trails so clearly defined as the trail he sees here, leading through a pinewoods, and out of sight.

Nor is there a plank bridge at the lake quite like this bridge, so far as he can recall.

How lost he feels! No idea how old he is, or where the others are. No idea if he is hungry, if he has eaten recently or not for a very long time.

The others. Scarcely knows what this means: parents, grandparents, adult relatives, young and elder cousins. A child has but a vague sense of others. Apart from relatives, many adults seem interchangeable—faces, names. Ages.

So many adults, in a child’s life! Children nearer his age, for instance young cousins, are more vividly delineated and named.

Where is Gretchen?—she has gone away.

When will you see Gretchen again?—maybe not for a while.

He is trying to recall if this is before the “search party”—(but why would there be a “party”—in the woods? Why a “party” when the girl is gone away somewhere, and the adults are sad?)—or after; if this is before Granddaddy insisted upon taking up the Beechcraft, and had to make an emergency landing on one of the islands.

Trying to recall if the fever in his brain is the fire from the crash, or the fire in the hospital.

Beyond the plank railing is a shallow stream. He has been hearing the murmurous sound of the flowing water for some time, without realizing. Only when he sees the stream, and identifies the flowing water, does he hear it.

Gripping the railing tightly in both hands. Standing with his feet apart, to brace himself against a sudden wind. (Though there is no wind.) Facing a marshy area dense with swamp grasses, tall reeds, pussy willows and cattails. Trees denuded of bark, hunched over like elderly figures, choked with vines. A smell of wet, rotted things. And everywhere, strips of shimmering water like strips of phosphorescence that glow in the dark as warnings.

Below the plank bridge—so loosely fitted, you can see between the boards—is the shallow stream that flows so slowly you can scarcely determine in which direction water is flowing.

And on the water’s surface he sees something curious, that makes him smile: small antic winged insects—“dragonflies.”

He has not seen these glittery insects until now, leaning over the railing. And there are others—“skaters.” (How does he know these names? Effortless as the meandering stream, and as near-imperceptible, “skaters” and “dragonflies” float into his thoughts.)

He has heard of “dragon”—and he has heard of “fly.” It is a novel thing, to put them together: “dragonfly.” He did not do this, he thinks. But someone did.

He has been leaning over the plank railing, staring down. His mouth is slightly open, he breathes quickly and anxiously. For he is in the presence of something profoundly significant whose meaning is hidden to him—which causes him to think that he must be very young. He is not the other, older Elihu—that has not happened yet.

This is a relief! (Is this a relief? For whatever will happen, will happen.)

He sees: what is arresting about the insects is that their shadows are magnified in the streambed a few inches below the surface of the water upon which they swim. If you observe the shadows that are rounded and soft-seeming you could not deduce that they have been cast by the insects with their sharply-delineated wings.

If you observe the shadows below, you can’t observe the insects. If you observe the insects, you can’t observe the shadows.

He is beginning to feel a mild anxiety in the region of his chest—he does not know why.

He sees, beyond the marsh are low-lying shapes—“hills.” Though these could be stage sets, painted to resemble “hills.”

He has not turned to look around, to see what is behind him. It is crucial, he must not look behind him. That is why he is gripping the plank railing so tightly, and why he stands with his feet apart, to steady himself.

Will not look. Has not (yet) seen the girl’s body in the shallow stream.

“ELI, THANK YOU!”

Carefully, Margot spreads E.H.’s most recent drawings and charcoal sketches on a table.

Dozens of pages from E.H.’s oversized sketchbook.

Dark, shadowed scenes—it isn’t clear what their subjects are—interiors? forests? caves? Here and there, a barely recognizable human figure, crouching in darkness.

In admiring silence Margot stares at the pages from E.H.’s sketchbook. The pencil drawings are meticulously drawn, the charcoal sketches light and feathery. Margot has learned to be cautious in her response to E.H.’s art—the man’s affable manner can alter swiftly at such times. (There is a side to E.H. few have seen: sudden fury, unexpressed except by a tightening of facial muscles, a clenching of fists.) In fact, Margot Sharpe is the only person she knows, including Milton Ferris himself, who has been allowed by E.H. to see his art. This is flattering—E.H. trusts her.