Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

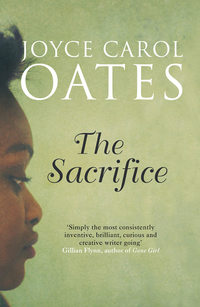

Kitabı oku: «The Sacrifice», sayfa 3

Mrs. Frye’s fear of the police officers appeared to be genuine.

By this time Sybilla Frye was sitting up on the gurney with her knees raised against her chest trying to hide herself with the crinkly white paper and making a noise like Nnn-nnn-nnn—like she was so frightened, she was shivering convulsively. You could hear her teeth chatter. And now she was crying, like a child Mama don let them take me, Mama take me home …

The mud and dog-feces had been removed from the girl’s hair.

We’d had to cut and clip some of her hair in order to get this matter out. It would be charged afterward that we had defiled and disfigured Sybilla Frye—we had deliberately cut her hair in a careless and jagged fashion.

Her body covered in filth had been washed but the racist slurs in black Magic Marker ink remained on her torso and abdomen, more or less indecipherable.

(It would be recorded in the ER photos that these words had been written upside-down on Sybilla Frye’s body.)

(Well, you’d think—as if Sybilla Frye had written the words herself, right? But a clever assailant might’ve written the words on her body standing behind her so that she could read the words. Or—he’d written the words upside-down purposefully so the victim would be accused of lying. That was possible.)

(Seeing the racist words on the girl’s body we’d had to notify the FBI right then. This is protocol if there is a probable “hate crime” as there certainly was in this case.)

In an emergency unit in a city like Pascayne, New Jersey, you are half the time reporting crimes and taking such photos for forensic use. If your patient dies, you may be the only witnesses.

The FBI had to be notified immediately which the ER administrator did without either the injured girl or her mother knowing at the time.

Mrs. Frye was demanding to speak with her daughter “in private” if we wouldn’t release the girl so she could take her home. Dr. D___ allowed this.

Mrs. Frye jerked the curtain shut around the cubicle.

For some minutes, Mrs. Frye and Sybilla whispered together.

Police officers were asking the ER staff and the EMTs what had happened and we told them what we knew: Mrs. Frye had ID’d her daughter who was “Sybilla Frye”—“fourteen years old”—(in fact, it would be revealed later that Sybilla Frye was actually fifteen: she’d been born in September 1972); the girl had been assaulted and had sustained a number of injuries; she’d been struck by fists and kicked, but she didn’t seem to have been attacked with any weapons; cuts in her face had been made with a fist or fists, not a sharp instrument; there were no gunshot wounds; her face, torso, belly, legs and thighs were bruised, and there appeared to be evidence of bruising in the vaginal area, but without a pelvic exam it wasn’t possible to determine if there had been sexual penetration or any deposit of semen.

Skin samples taken from the girl’s body would be tested for DNA and these might contain semen. Other tests would be run, to determine if a sexual offense had been committed.

Mrs. Frye had claimed that her daughter had been “kidnapped” and “locked up” somewhere for three days and three nights. During this time, Mrs. Frye had been looking for the girl “everywhere she knew” but no one had seen her. Then, that morning, Sybilla Frye had been discovered by a woman who lived near the Jersey Foods factory, who’d heard the girl “crying and moaning” in the night.

So far, Sybilla Frye had not identified nor even described her assailant or assailants. She had not communicated with the ER staff at all.

She had not allowed a pelvic exam, nor had she consented to a blood test.

Despite the mother’s claim that she’d been kept captive somewhere for three days, Sybilla Frye did not appear malnourished or dehydrated.

This is some of what we told Pascayne police.

After approximately ten minutes of whispered consultation, Mrs. Frye drew back the curtain. She was deeply moved; her face was bright with tears. She’d been wiping her daughter’s face with tissues and now she was demanding that she be allowed to take her daughter home, it was a “free country” and unless they was arrested she was taking S’billa home.

(Ednetta Frye would afterward claim that she’d had to clean her daughter of mud and dog shit herself, the ER staff had not “touched a cloth” to Sybilla. She would claim that she’d carried her baby in her arms out of the ER, filth still in the girl’s hair and on her body, and her body naked, covered in only a “nasty” blanket as the ER staff had cut off her clothes for “evidence.”)

An officer from Juvenile Aid had arrived. But Mrs. Frye refused to allow Sybilla to speak to this woman, as she’d refused to allow Sybilla to speak to the officer from Child Protective Services.

It was explained to Mrs. Frye that since a crime or crimes had been committed, Sybilla would have to be interviewed by police officers—she would have to give a “statement”—when she was well enough … Mrs. Frye said indignantly That girl aint gon be “well enough” for a long time so you just let her alone right now. I’m warnin you—let my baby an me alone, we gon home right now or I’m gon sue this hospital an every one of you for kidnap and false imprisonment.

But finally Mrs. Frye relented, saying she would allow Sybilla to talk to a cop—One of her own kind, and a woman—if you have one in that Pas’cyne PD.

The Interview

It was not an ideal interview. It did not last beyond twenty stammered minutes.

It would be the most frustrating interview of her career as a police officer.

She’d been bluntly told that a black girl beaten and (possibly) gang-raped had requested a black woman police officer to interview her at the St. Anne’s ER.

Getting the summons at her desk in the precinct station late Sunday morning she’d said, D’you think I’m black enough, sir?—in such a droll-rueful way her commanding officer couldn’t take offense.

She couldn’t take offense, she understood the circumstances.

She was not minority hiring. She didn’t think so.

She’d been on the Pascayne police force for eleven years. She had a degree from Passaic State College and extra credits in criminology and statistics as well as her police training at the New Jersey Academy. She was thirty-six years old, recently promoted to detective in the Pascayne PD.

As a newly promoted detective she worked with an older detective on most cases. This would be an exception.

Iglesias did not check black when filling out appropriate official forms. Iglesias did not think of herself as a person of color though she acknowledged, seeing herself in reflective surfaces beside those colleagues of hers who were white, that she might’ve been, to the superficial eye, a light-skinned Hispanic.

Her (Puerto Rican–American) mother wasn’t her biological mother. Her (African-American) father wasn’t her biological father. Where they’d adopted her, a Catholic agency in Newark, there was a preponderance of African-American babies, many “crack” and “HIV” babies, and Iglesias did not associate herself with these, either. Her (adoptive) grandparents were a mix of skin-colors, a mix of racial identities—Puerto Rican, Creole, Hispanic, Asian, African-American and “Caucasian.” There was invariably a claim of Native-American blood—a distant strain of Lenape Indians, on Iglesias’s father’s side. The Iglesias family owned property in the northeast sector of Pascayne adjacent to the old, predominantly white sector called Forest Park; they owned rental properties and several small stores as well as their own homes. It was not uncommon for a young person in Iglesias’s family to go to college—Rutgers-Newark, Rutgers–New Brunswick, Bloomfield College, Passaic State. The most talented so far had had a full-tuition scholarship from Princeton. They did not think of themselves and were not generally thought of as black.

Iglesias did not take offense, being so summoned to St. Anne’s ER. Something in her blood was stirred, like flapping flags in some high-pitched place, by the possibility of being in a position unique to her.

For racism is an evil except when it benefits us.

She liked to think of being a police officer as an opportunity for service. If not doing actual good, preventing worse from happening. If being a light-skinned female Hispanic helped in that effort, Ines Iglesias could not take offense and would not take offense except at the very periphery of her swiftly-calculating brain where dwelt the darting and swooping bats of old hurts, old resentments, old violations and old insults inflicted upon her haphazardly and for the most part unconsciously by white men, black men, brown-skinned men—men.

With excitement and apprehension Sergeant Iglesias drove to St. Anne’s Hospital. The emergency entrance was at the side of the five-story building.

This was not a setting unfamiliar to Ines Iglesias. She had witnessed deaths in this place and not always the deaths of strangers.

Just inside the ER, a patrol officer led her into the interior of the unit where the (black) girl believed to have been gang-raped was waiting, inside a curtained cubicle.

In the ER she noted eyes moving upon her—fellow cops, medics—in wonderment that this was the officer sent to the scene as black.

Cautiously Iglesias drew back the curtain surrounding the gurney where the stricken girl awaited. And there, in addition to the girl, was the girl’s mother Ednetta Frye.

Sybilla Frye was a minor. Her mother Ednetta Frye had the right to be present and to participate in any interview with Sybilla conducted by any Pascayne police officer or social worker.

Too bad! Iglesias knew this would be difficult.

Iglesias introduced herself to Sybilla Frye who’d neither glanced at her nor given any sign of her presence. She introduced herself to Ednetta Frye who stared at her for a long moment as if Mrs. Frye could not determine whether to be further insulted or placated.

Iglesias addressed Mrs. Frye saying she’d like to speak to Sybilla for just a few minutes. “She’s had a bad shock and she’s in pain so I won’t keep her long. But this is crucial.”

Iglesias had a way with recalcitrant individuals. She’d been brought up needing to charm certain strong-willed members of her own family—female, male—and knew that a level look, an air of sisterly complicity, shared indignation and vehemence were required here. She would want Mrs. Frye to think of her as a mother like herself, and not as a police officer.

Extending her hand to shake Ednetta Frye’s hand she felt the suspicious woman grip her fingers like a lifeline.

“You ask her anythin, ma’am, she gon tell you the truth. I spoke with her and she ready to speak to you.”

Mrs. Frye spoke eagerly. Her breath was quickened and hoarse.

Not a healthy woman, Iglesias guessed. She knew many women like Ednetta Frye—overweight, probably diabetic. Varicose veins in her legs and a once-beautiful body gone flaccid like something melting.

Yet, you could see that Mrs. Frye had been an attractive woman not long ago. Her deep-set and heavy-lidded eyes would have been startlingly beautiful if not bloodshot. Her manner was distraught as if like her daughter she’d been held captive in some terrible place and had only just been released.

But when Iglesias tried to speak to Sybilla Frye, Mrs. Frye could not resist urging, “You tell her what you told me, S’b’lla! Just speak the words right out.”

The battered girl sat slumped on the gurney wrapped in a blanket, shivering. Iglesias found another blanket, folded on a shelf, and brought it to her, and drew it around her thin shoulders. Close up, the girl smelled of disinfectant but also of something foul and nauseating—excrement. Her hair was oily and matted and had been cut in a jagged fashion as if blindly.

With both adult women focused upon her, Sybilla seemed to be shrinking. Her shut-in expression was a curious mixture of fear, unease, apprehension, and defiance. She seemed more acutely aware of her mother than of the plainclothes police officer who was a stranger to her.

Between the daughter and the mother was a force field of tension like the atmosphere before an electric storm which Iglesias knew she must not enter.

Iglesias asked the girl if she was comfortable?—if she felt strong enough to answer a few questions?—then, maybe, if the ER physician OK’d it, she could go home.

A trauma victim resembles a wounded animal. Trying to help, you can exacerbate the hurt. You can be attacked.

“Sybilla? Do you hear me? My name is Ines—Ines Iglesias. I’m here to speak with you.”

Gently Iglesias touched Sybilla’s hand, and it was as if a snake had touched the girl—Sybilla jerked back her hand with an intake of breath—Ohhh!

There was something childish and annoying in this behavior, Iglesias thought. But Iglesias wanted to think The girl has been badly hurt.

Mrs. Frye said sharply to her daughter, “I’m tellin you, girl. You just answer this p’lice off’cer’s questions, then we goin home.”

Sybilla continued to hunch shivering inside the blanket. She had shut her eyes tight as a stubborn child might do. Her upper lip, swollen like a grotesque discolored fruit, was trembling.

Iglesias had been told that the girl’s assailants had rubbed mud and dog excrement into her hair and onto her body and that they’d written racist words in black ink on her body.

When she asked if she might see these words, Sybilla stiffened and did not reply.

“If you could just open the blanket, for a minute. The curtain is closed here. No one will see. I know this is very unpleasant, but …”

Sybilla began shaking her head vehemently no.

In a plaintive voice Mrs. Frye said, “She don’t need to do that no more, Officer. S’b’lla a shy girl. She don’t show her body like some girls. They took pictures of the writing, they can show you. That’s enough.”

“I would so appreciate it, if I could see this ‘writing’ myself.”

“Ma’am, that nasty writin is all but gone, now. I think they washed it off. But they took pictures. You go look at them pictures.”

“If I could just—”

“I’m tellin you no, ma’am. It’s enough of this for right now, S’billa comin home with me.”

Iglesias had been briefed about the “racist slurs”—scribbled onto the girl’s body “upside-down.” Clearly it was already an issue to arouse skepticism—upside-down? She would study the photos and see what sense this might make.

Iglesias had placed a recording device on the examination table. Mrs. Frye objected: “You recordin this, ma’am? I hope you aint recordin this, I can’t allow that.”

The small spinning wheels were a provocation. Iglesias had known that Mrs. Frye would object.

Carefully she explained that it was police department policy that such an interview would be recorded. “A recorded interview is for the good of everyone involved.”

“No it ain’t, ma’am! Like with pictures you can mess up what people say to twist it how you want. Like on TV. You can leave out some words an add some others the way police do, to make people ‘confess’ to somethin they ain’t done. You got to know that, you a cop you’self.”

Mrs. Frye spoke sneeringly. The sudden hostility was a surprise.

Iglesias had wanted to think that she’d been persuading Mrs. Frye, making an ally of her, and not an adversary. It was a painful truth, what the woman was saying, yet, as a police officer, she had to pretend that it wasn’t so.

“Not in this case, Mrs. Frye. Not me.”

Mrs. Frye folded her arms over her heavy breasts. She was wearing what appeared to be several layers of clothing—pullover shirt, long-sleeved shirt, sweater, and slacks. On her small wide feet, frayed sneakers. Iglesias saw that Ednetta Frye’s nails had been done recently, each nail painted a different color, zebra-stripes on both thumbnails, but the polish was chipped and the nails uneven. The girl’s nails were badly broken and chipped but had been polished as well, though not recently. The daughter wore no jewelry except small gold studs in her ears. The mother wore gold hoop earrings, a wristwatch with a rhinestone-studded crimson plastic band, rings on several fingers including a wedding band that looked too small for her fleshy finger.

“See, ma’am, I can’t allow my daughter to be any more mishandled than she’s been. No recordin here, or we goin home right now.”

The woman didn’t remember Iglesias’s name or rank. You had to suppose. She didn’t intend a sly insult, calling Iglesias ma’am.

Iglesias could only repeat that recording their conversation was for the good of everyone concerned but Mrs. Frye interrupted—“Nah it ain’t! You must think we are stupid people! Have to be pretty damn stupid not to know that white cops turn your word around on you, or say you goin for a ‘weapon’ when you’re reachin for your driver’s license so they can shoot you down dead.”

Iglesias spoke carefully to the excited woman saying she understood her concern, but this was an entirely different situation. In the heat of confrontations, terrible mistakes sometimes happened. But allowing Iglesias to record a conversation with her daughter, in the safety of the ER, was not the same thing at all.

Mrs. Frye said, snorting with indignation, that that was just some white folks’ bullshit.

Iglesias said, pained, that “white folks” had nothing to do with this—with them. They could both speak frankly to her, that was why she’d come to speak with them.

Mrs. Frye was unimpressed. She said to Sybilla she was going to get her some decent clothes to put on, and they were getting out of this place. Unless they were arrested, nobody could keep them.

“Mrs. Frye, please—let me speak to Sybilla without recording our conversation. For just a few minutes.”

Iglesias had no choice but to relent, the woman was about to take away the girl. Arranging for another interview would be very difficult.

“Nah I’m thinking we better be goin. Talkin with you aint worked out like I hoped, see, ma’am, you one of them.”

Mrs. Frye spoke contemptuously. Iglesias felt dismay.

I am one of you, not one of them. Believe me!

“Please, Mrs. Frye. Just a few minutes. No recording.”

All this while Sybilla had been sitting mute and shivering. Only vaguely had she seemed to be listening to the adult women, with an air of disdain.

Iglesias saw herself in the girl, she believed to be fourteen. She saw herself at that age, sulky, sullen, defiant and scared.

She’d been sexually molested, too. More than once. And many times sexually harassed and threatened. But never raped, never brutally beaten. Not Ines Iglesias.

The Fryes lived on Third Street, in that run-down neighborhood by the river. Abandoned factories, shuttered and part-burned houses, streets clogged with abandoned and rusting vehicles. Pascayne South High, lowest-ranked in the city. The Fifth Precinct, with the highest crime rate. You had to grow up swiftly there.

In the Iglesias neighborhood, adjacent to Forest Park, there were blocks of single-family homes, neatly tended lawns and attached garages. There were streets not clogged with parked, abandoned vehicles. There was Forest Park High from which an impressive number of students went on to college and where there were no fights, knifings, rapes on or near the premises.

But I am one of you! Please trust me.

Though she hadn’t grown up in the inner city, Iglesias had had good reason to fear and distrust the Pascayne police. Family members, relatives, friends, neighbors had had encounters with (white) police of which you had to say the good thing was, none of these encounters had been fatal.

Though she knew of encounters that had been fatal.

Though she knew police officers who were racists, even now—in 1987. After the Pascayne PD had been “integrated” for twenty years.

It was a mark of their contempt for her, she supposed—making racist remarks when she could overhear.

Yet, racist remarks that weren’t directed toward her or her kind—light-skinned Hispanic.

It was African-Americans they held in particular contempt—niggers.

Though maybe behind her back, in their careless, jocular way, that exaggerated the bigotry they naturally felt in the service of humor, they referred to her as nigger, too.

Iglesias not bad-lookin for a nigger, is she?

Man, not bad!

Got her an ass on her.

I seen better.

In a quiet urging voice Iglesias was telling Sybilla Frye how she wanted to help her. How she wanted to know who’d hurt her so badly, who the assailant or assailants were so that they could be arrested, gotten off the street.

With a little shiver of dread Sybilla drew the blanket closer around her. She seemed to be rousing herself out of a dream.

Shaking her head looking now scared and miserable. Iglesias was wondering how a rape victim returned to her life—to school, to her friends. Already news of the missing Frye girl found hog-tied in the canning factory was on the street.

Sybilla leaned to her mother and murmured in her ear. Her swollen lips moved but Iglesias couldn’t make out what she was whispering.

“Oh honey, I know,” Mrs. Frye said to the girl; then, to Iglesias, with grim satisfaction, “S’b’lla sayin they gon kill her, ma’am. Told her they gon kill her whole family, she tells you.”

It was strange how Mrs. Frye addressed her daughter gently and lovingly, or harshly and reproachfully. If you were the daughter you would have no way of guessing which Mama would emerge.

Though generally, it was safe to surmise that when Sybilla did not oppose her mother in any way, in even the expression on her face, the tilt of her head or the set of her back, the gentle-loving Mama emerged.

“But we can protect you, Sybilla. We can put you in protective custody until your assailants are arrested.”

Iglesias was a police officer, she said such improbable things.

How many times uttered by police officers in such situations in Pascayne, to whatever futile end.

“Off’cer, that is such bullshit. Half the people we know believe that shit you tell them, they shot down dead in the street. Whoever do it don bother waitin for dark, he just shoot. You aint bein honest with my daughter an me, an you know it. Why I asked for an African-American woman, and you aint her.”

“I am her. I’m here to help you.”

“You a woman, you got to know what they gon do to my daughter if she say who hurt her. All she told me, it was five of them—men. Men not boys. Nobody she knew, from the neighborhood or her school. That’s all she told me, she’s too scared.” Mrs. Frye smiled a sharp mirthless smile revealing a gap between her two front teeth like an exclamation mark.

Iglesias tried again with Sybilla. “So—you say—it was five men? No one you recognized? Could you begin at the beginning, please? Your mother says you went missing on Thursday …”

Slowly then, as if each word were a painful pebble in her mouth, Sybilla began to speak in a hoarse whisper. She was squirming inside the blanket, looking not at the police officer who’d fixed her face into an expression of extreme solicitude and interest but staring at the floor. There appeared to be a slight cast in her left eye. Perhaps this was why she didn’t look up. Iglesias could not determine if the girl was genuinely frightened or if there was something childishly resistant and even defiant about her—an attitude that had to do less with Iglesias than with the mother who remained at all times close beside her, half-sitting on the examination table, a physical presence that must have been virtually overwhelming to the girl yet from which she had no recourse.

Iglesias could see that, though Sybilla’s eyes were swollen and discolored, these were Ednetta Frye’s eyes: thick-lashed, so dark as to appear black, large and deep-set. During her hurried briefing Iglesias had been told that the victim was possibly mentally defective, maybe retarded, which was why it was so difficult to communicate with her, but Iglesias didn’t think this was true.

Iglesias asked Sybilla to repeat what she’d said, a little louder. She was leaning close, to listen.

In the hoarse slow whisper Sybilla recounted how she’d been coming home from school Thursday afternoon when somebody, some men, came up behind her with a canvas they lowered over her head and grabbed her and dragged her away in a van and kept her there for three days—she thought it was three days, she wasn’t sure because she was not conscious all the time—and punched and kicked her and did things to her and laughed at her when she was crying and later put mud and dog shit onto her and wrote on her “nasty words” and tied her up and left her in the factory cellar saying there were “other nigras” in that place who had died there.

Starting to cry now, and Mrs. Frye squeezed her hand, and for a moment it didn’t seem that Sybilla would continue.

Iglesias asked if she’d been able to see faces? Could she describe the men—their age, race? Were they known to her?

Sybilla shook her head, they weren’t known to her. She seemed about to say more, then stopped.

“You’re sure that these men are not known to you, Sybilla? Could you describe any of them?”

Sybilla stared at the floor. Tears welled in her eyes and spilled over her bruised cheeks.

“Did they hurt you sexually?”

Sybilla sat very still staring at the floor. Her face was shiny now with tears.

Mrs. Frye said, gently urging, “S’b’lla, honey, you got to tell this lady, see? You got to tell her what you can. You aint told me all of it, has you?—you know you aint. Now, you tell her.”

“Did they rape you, Sybilla?”

Sybilla shook her head just slightly, yes.

“More than one man, you’ve said?”

Sybilla shook her head yes.

“You told your mother—five men?”

Sybilla shook her head yes.

“Not boys but men.”

Sybilla shook her head yes.

“And not men you know?”

Sybilla shook her head no.

“Can you describe them? Just—anything.”

Sybilla stared at the floor. Mrs. Frye was crowded close beside her now, an arm around the girl’s shoulders.

“The color of their skin? You said they used the word nigra—”

Mrs. Frye urged her to speak. “Come on, girl! Was they black men, or—some other? Who’d be sayin ‘nigra’ except some other?”

Sybilla stared at the floor. She didn’t seem resistant or defiant now, but exhausted. Iglesias worried that the girl was about to faint or lapse into some sort of mental state like catatonia.

Once, interviewing a stricken and near-mute girl of twelve, Iglesias had given the girl Post-its upon which to write, and the girl had done so. Iglesias gave Sybilla a (bright yellow, cheering) Post-it pad and a pencil to write on and, after some hesitation, Sybilla printed: