Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime»

JUDITH FLANDERS

The Invention of Murder

How the Victorians Revelled in Death and

Detection and Invented Modern Crime

For Susan and Ellen without whom …

CONTENTS

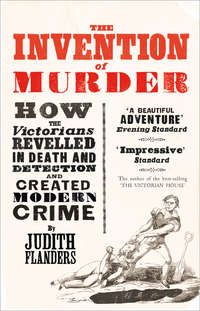

Cover

Title Page

TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS

A NOTE ON CURRENCY

ONE Imagining Murder

TWO Trial by Newspaper

THREE Entertaining Murder

FOUR Policing Murder

FIVE Panic

SIX Middle-Class Poisoners

SEVEN Science, Technology and the Law

EIGHT Violence

NINE Modernity

NOTES

SOURCES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS

‘The funeral of the murdered Mr. and Mrs. Marr and infant son’, broadside of c.1811. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Crime 10[13])

‘The public Exhibition of the Body of Williams’, from The New Newgate Calendar, Vol. V by Andrew Knapp and William Baldwin, c.1826.

‘The pond in the garden, into which Mr. Weare was first thrown’, from Pierce Egan’s Account of the Trial of John Thurtell and Joseph Hunt, 1824.

‘Execution of William Corder at Bury, August 11 1828’, from An Authentic and Faithful History of the Mysterious Murder of Maria Marten by J. Curtis, 1828.

‘Elegiac Lines on the Tragical Murder of Poor Daft Jamie’, broadside of 1829. (National Library of Scotland, Ry.III.a.6[017])

‘New’ policeman, from a song-sheet c.1830. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

‘Apprehension of the Murderer of the Female whose Body was found in the Edgware Road in December last’, broadside of 1837. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Broadsides: Murder & Executions Folder 6[5])

‘Two sudden blows with a ragged stick and one with a heavy one’, illustration by William Harvey for ‘The Dream of Eugene Aram, The Murderer’ by Thomas Hood, 1831.

Playbill for Jim Myers’ Great American Circus at the Pavilion Theatre, June 1859, including Turpin’s Ride to York, or, The Death of Bonny Black Bess. (Theatre & Performance Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, London/© V&A Images)

‘“Parties” for the gallows’, Punch cartoon, 1845.

‘Interior of the court-house, during the trial of Rush – examination of Eliza Chestney’, from the Illustrated London News, 7 April 1849. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

‘See, dear, what a sweet doll Ma-a has made for me’, Punch cartoon, 1850.

‘Madame Tussaud her wax werkes: ye Chamber of Horrors!!’, Punch cartoon, 1849.

‘Execution of the Mannings’, broadside of 1849. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Crime 2[5])

‘The Telegraph Office’, from The Progress of Crime: or, Authentic Memoirs of Marie Manning by Robert Huish, 1849. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘Awful Murder of Lord William Russell, MP’, broadside of 1840. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection/JJ Broadsides: Murder & Executions Folder 10[29])

Advertisement for Dr. Mackenzie’s Arsenical Toilet Soap, 1898.

‘Sarah Chesham’s Lamentation’, broadside of c.1851. (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford: Firth c.17[261]) ‘Fatal facility; or, Poisons for the asking’, Punch cartoon, 1849. Thomas Griffiths Wainewright, self-portrait, from Janus Weathercock by Jonathan Curling, 1938.

‘Drs. Taylor and Rees performing their analysis’, from Illustrated and unabridged edition of the Times report of the trial of W. Palmer for poisoning J.P. Cook, 1856. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘The Life, Confession and Execution of Mrs. Burdock’, broadside of 1835. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘Copy of Verses on the Awful Murder of Sara Hart’, broadside of 1845. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011) Execution of Henry Wainwright, from Supplement to the Illustrated Police News, 21 December 1875. (Guildhall Library, City of London/The Bridgeman Art Library)

William Terriss and W.L. Abingdon in The Fatal Card, 1894. (Theatre & Performance Collection, Victoria & Albert Museum, London/© V&A Images)

‘Murder and mutilation of the body’, from The Alton Murder! The Police News edition of the life and examination of Frederick Baker, 1867. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

‘“Scott”, alias E. Sweeney, of Ardlamont mystery fame’, from the Graphic, 14 April 1849. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Portrait of Mary Eleanor Wheeler (alias Pearcey), pencil, pen and ink drawing by Sir Leslie Ward, 1890. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

‘Removing Lipski from under the bed’, from the Illustrated Police News, 9 July 1887.

‘Horrible London; or, The pandemonium of posters’, Punch cartoon, 1888.

‘With the Vigilance Committee in the East End’, from the Illustrated London News, 13 October 1888. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Advertisement for ‘The Great Surprise Watch’ from M.J. Haynes & Co.’s Specialities,1889. (© The British Library Board. All rights reserved 2011)

A NOTE ON CURRENCY

Pounds, shillings and pence were the divisions of British currency in the nineteenth century. One shilling was made up of twelve pence; one pound of twenty shillings, i.e. 240 pence. Pounds were represented by the £ symbol, shillings as ‘s.’, and pence as ‘d.’ (from the Latin denarius). ‘One pound, one shilling and one penny’ was written as £1.1.1. ‘One shilling and sixpence’, referred to in speech as ‘One and six’, was written as 1s.6d., or ‘1/6’.

A guinea was a coin to the value of £1.1.0 (the coin was not circulated after 1813, although the term remained and tended to be reserved for luxury goods). A sovereign was a twenty-shilling coin, a half-sovereign a ten-shilling coin. A crown was five shillings, half a crown 2/6, and the remaining coins were a florin (two shillings), sixpence, a groat (four pence), a threepenny bit (pronounced ‘thrup’ny’), twopence (pronounced ‘tuppence’), a penny, a halfpenny (pronounced hayp’ny), a farthing (a quarter of a penny) and a half a farthing (an eighth of a penny).

Relative values have altered so substantially that attempts to convert nineteenth-century prices into contemporary ones are usually futile. However, the website http://www.ex.ac.uk/~RDavies/arian/current/howmuch.html is a gateway to this complicated subject.

‘We are a trading community – a commercial people. Murder is, doubtless, a very shocking offence; nevertheless, as what is done is not to be undone, let us make our money out of it.’

‘Blood’, Punch, 1842

ONE Imagining Murder

‘Pleasant it is, no doubt, to drink tea with your sweetheart, but most disagreeable to find her bubbling in the tea-urn.’ So wrote Thomas de Quincey in 1826, and indeed, it is hard to argue with him. But even more pleasant, he thought, was to read about someone else’s sweetheart bubbling in the tea urn, and that, too, is hard to argue with, for crime, especially murder, is very pleasant to think about in the abstract: it is like hearing blustery rain on the windowpane when sitting indoors. It reinforces a sense of safety, even of pleasure, to know that murder is possible, just not here. At the start of the nineteenth century, it was easy to think of murder that way. Capital convictions in the London area, including all the outlying villages, were running at a rate of one a year. In all of England and Wales in 1810, just fifteen people were convicted of murder out of a population of nearly ten million: 0.15 per 100,000 people. (For comparison purposes, in Canada in 2007–08 the homicide rate was 0.5 per 100,000 people, in the EU, 1.8 per 100,000, in the USA 2.79, while Moscow averaged 9.6 and Cape Town 62 per 100,000.)

Thus, when on the night of 7 December 1811 a twenty-four-year-old hosier named Timothy Marr, his wife, their baby and a fourteen-year-old apprentice were all found brutally murdered in their shop on the Ratcliffe Highway in the East End of London, the cosy feeling evaporated rapidly. The year 1811 had not been kind to the working classes. The French wars had been running endlessly, and with Waterloo four years in the future, there was no sense that peace – and with it prosperity – would ever return. Instead hunger was ever-present: the wars and bad harvests had savagely driven up the price of bread. In the early 1790s wheat had cost between 48s. and 58s. a quarter; in 1800 it was 113s.

The murder of the Marrs, however, was more dramatic than the slow deaths of so many from hunger, or the faraway deaths of soldiers and sailors in unending war, and the story was soon everywhere. The Ratcliffe Highway was a busy, populous working-class street in a busy, populous working-class area near the docks. At around midnight on the evening of his death, Marr was ready to shut up shop. (Working-class shops regularly stayed open until after ten, to serve their clientele on their way home after their fourteen-hour workdays. On Saturdays, pay day, many shops closed after midnight.) The hosier sent his servant, Margaret Jewell, to pay an outstanding bill at the baker’s, and to buy the family supper. After paying the bill she looked for an oyster stall. Oysters were a common supper food, being cheap, on sale at street stalls and needing no cooking. The first stall she came to had shut up for the night, and looking for another she lost her bearings – before gas lighting streets had only the occasional oil lamp in a window to guide passers-by – and was away for longer than expected, returning around 1 a.m.* She knocked; knocked again. She heard scuffling, someone breathing on the other side of the door, but no one opened it. She stopped the parish watchman on his rounds, telling him she knew the Marrs were in, she had even heard them, but no one was answering the door. He had passed by earlier, he said, and had tapped on the window to tell Marr that one of his shutters was loose. A man had called out, ‘We know it!’ Now he wondered who had spoken.

Their talking attracted the attention of Marr’s next-door neighbour, a pawnbroker. From his window he could see that the Marrs’ back door was open. With the encouragement of the neighbours and the watchman, he climbed the fence between the houses and entered (some reports say it was the watchman who entered). Whichever man it was, once inside he found a scene from a horror film. Marr and his apprentice were lying in the shop, battered to death. The apprentice had been attacked so ferociously that fragments of his brains were later found on the ceiling. Blood was everywhere. Mrs Marr was lying dead halfway to the door leading downstairs. The pawnbroker staggered to the front door, shouting, ‘Murder – murder has been done!’ and the watchman swung his rattle to summon help. Soon an officer from the Thames Division Police Office appeared. Meanwhile Margaret Jewell rushed in with a group of excited bystanders, looking for the baby. They found him lying in his cradle in the kitchen, his throat cut. Some money was scattered on the shop counter, but £150 Marr had tucked away was untouched. On the counter lay an iron ripping chisel, which seemed not to have been used; in the kitchen, covered with blood and hair, was a ship’s carpenter’s peen maul – a hammer with sharpened ends. A razor or knife must have been used on the baby, but none was found. Outside the back door were two sets of bloody footprints, and a babble of voices reported that a couple of men, maybe more, no one was quite sure, had been seen running away from the general direction of the Marrs’ house at more or less the right time.

In the morning, a magistrate from the Thames Division Police Office took over the case. An officer from the Thames Division Police Office had responded the night before, and therefore the magistrates at the Thames Office were now in charge. A magistrate ordered the printing of handbills offering a reward, and visited the site of the murder, where the bodies lay where they had fallen the night before.

He was not the only one. What might be termed murder-sightseeing was a popular pastime, and many went ‘from curiosity to examine the premises’, where they entered ‘and saw the dead bodies’. Inquests were held as quickly as possible after the event, usually at a public house or tavern near the scene of the crime. The bodies were left in situ for the jury to view. Until they had been, visitors traipsed through the gore-spattered rooms, peering not only at the blood splashes and other grisly reminders of the atrocity, but also at the bodies themselves.

For those who wanted a tangible souvenir, there were always broadsides, which were swiftly on sale on street corners. Broadsides had been around since the sixteenth century, but modern technology made their production easier, cheaper and quicker, and their distribution more widespread. A typical broadside was a single sheet, printed on one side, which was sold on the street for ½d. or 1d. Broadsides had their heyday before the 1850s, when newspapers were expensive. Most commonly, sheets were produced sequentially for each crime that caught the public’s imagination: the first report of the crime, with further details as they were revealed; the magistrates’ court hearing after an arrest; then the trial; and finally, and most profitably, a ‘sorrowful lamentation’ and ‘last confession’, usually combined with a description of the execution. These ‘lamentations’ and execution details were almost always entirely fabricated for commercial reasons: they found their readiest sale at the gallows, while the body was still swaying. For those who could not find a penny, pubs and coffee houses pinned up broadsides of popular crimes, to be read by customers as they drank. Other broadsides appeared in shop windows, frequently attracting crowds of bloodthirsty children.

One broadside, published before the Marrs’ inquest, which opened three days after the murders, reported that ‘the perpetrators are foreigners’, which could have done little to reassure readers in this dockyard area of town, filled with sailors from across the world. Another spent less time on the possible murderer, and more on the gory details and the rumours that were prevalent: that Mrs Marr had, several months before, discharged a servant for theft. ‘Words arose, when the accused girl is said to have held out a threat of murder. Mrs. Marr … gently rebuked her for using such language’; later Mrs Marr ‘remonstrated with her on her loose character and hasty temper’. Anyone with a penny to spare would get a fair idea of the crime and the latest news of the search for the murderer.

Those with a few more pennies could buy a pamphlet on the subject. These were available nearly as swiftly as the broadsides. One covered all the details of the inquest, so it was probably on sale within five days of the deaths. While the pamphlets looked more substantial at eight pages, much of their information was identical to that in the broadsides. In some, such similar wording is used that either they must have shared an author, or one was copied from the other. Mrs Marr again sacks her servant, who ‘is said to have held out a threat of murder. Mrs. Marr … gently rebuked her for using such language’; later she again ‘remonstrated with her on her loose character and hasty temper’. Now, however, we get the additional detail that the servant was leading a ‘prostituted life’. This is reinforced by a description of her clothes: ‘a white gown, black velvet spencer [jacket], cottage bonnet with a small feather, and shoes with Grecian ties’. No servant could afford such fashionable items: they were signs that her money was earned immorally.

Another way to savour the thrill of murder was to attend the funerals of the victims. Many people did so out of respect, as friends or as members of the same community. But far more did so out of curiosity. Still more read about them afterwards. Even four hundred miles away the Caledonian Mercury gave a detailed account of the funeral of the murdered apprentice: its readers were able to follow the precise path of the cortège as it travelled ‘from Ratcliffe-highway, through Well-close-square, up Well-street, to Mill-yard’. In Hull too newspaper readers followed the crowds that turned out for the Marrs’ triple funeral: ‘The people formed a complete phalanx from the [Marrs’] house to the doors of St. George’s church.’ The church itself was so crowded that the funeral procession could only enter ‘with some difficulty’. Then the paper gave the order of the procession, as was normally done for royal weddings and funerals, or the Lord Mayor’s parade:

The body of Mr. Marr;

The bodies of Mrs. Marr and infant;

The father and mother of Mr. Marr;

The mother of Mrs. Marr;

The four sisters of Mrs. Marr;

The only brother of Mr. Marr …

The friends of Mr. and Mrs. Marr.

Newspapers churned out stories, handbills circulated, witnesses were questioned. But none of this got any closer to finding the murderer or murderers. Then, like a recurring nightmare, twelve days after the Marrs’ deaths it all happened again. On 19 December a watchman found John Turner, half-dressed and gibbering with fear, scrambling down New Gravel Lane, a few hundred yards from the Ratcliffe Highway. He had gone to bed early at his lodgings above a public house. After closing time he heard screaming and he went part-way down the stairs, where he saw a stranger bending over a body on the floor. After a panicky attempt to leave via the skylight (he was so frightened he couldn’t find it), Turner tied his bedsheets together and slid out of the window into the yard, shouting, ‘They are murdering the people in the house!’ The watchman was quickly joined by neighbours, and they broke in through the cellar door to find, yet again, bodies lying with their heads beaten in and their throats cut. The body of John Williamson, the publican, was in the cellar; his wife Elizabeth had been in the kitchen with their servant Bridget. Only the Williamsons’ granddaughter, asleep upstairs, had escaped. Once more, money was scattered about, but little of value had been taken; once more, the escape was via the back door and over the yard fence.

The newspapers covered the story widely, but the information they gave was not terribly helpful. The Edinburgh Annual Register described John Turner as being ‘about six feet in height’, while The Times said he was ‘a short man’ with ‘a lame leg’. The Morning Chronicle described his ‘large red whiskers’, but thought he was ‘about five feet nine inches’ and ‘not lame’. Turner, therefore, was either tall, short, or in-between; he was lame, or possibly not; and he had large red whiskers, unless he didn’t. This was the description of a man who had stood in front of journalists at an inquest. Imagine how reliably the papers described the man briefly seen by Turner, or those who had been glimpsed running away from the Marrs’ house.

The police had no more idea where to look for the perpetrators of this new outrage than they had had after the deaths of the Marrs. They arrested plenty of people: people who were violent; people who looked in some way suspicious; people against whom a grudge was held. But one by one they were questioned and released.* In small communities criminals were usually revealed fairly swiftly; in areas with larger populations, handbills with descriptions of the wanted person and offers of rewards generally brought in information, frequently from fellow criminals who found this a convenient way of earning a bit of cash and removing a competitor at the same time. With no response to the initial reward offered after the murder of the Marrs, the only thing the magistrates could think to do was increase the sum. To the initial £50 reward, another £100 was added by the Treasury, and that was increased two days later to an astonishing £700 – a very comfortable middle-class annual income, the sign of increasing government anxiety, verging on panic. After the Williamsons were murdered, another 120 guineas was offered: twenty guineas to anyone who could identify the owner of the weapons, and 100 guineas more if that person were to be convicted of the murders.

One man, arrested on suspicion, attempted to turn king’s evidence, identifying eight men as his fellow murderers. Unable to come up with a motive, the newspapers attributed a love of wholesale slaughter to this mysterious gang. The gang theory was widely popular. A magistrate from the Thames Police Office wrote to his colleague at the Lambeth Street Office that the crime ‘gives an appearance of a gang acting on a system’, but to what end was not clear. Many were caught up: at one point seven men were held for questioning because ‘In the possession of one of them were found two shirts stained with marks very much resembling blood, and a waistcoat carrying also similar marks.’ The men turned out to be hop-pickers, and the stains were vine sap.

The first clue that led towards an arrest was noticed only on the day of the Williamsons’ murder, twelve days after the death of the Marrs, when it finally registered that the peen maul found in the kitchen had the initials ‘JP’ scratched on it. A handbill advertised this, and Mrs Vermiloe, the landlady of the Pear Tree Tavern, reported that her lodger, a Danish sailor named John Petersen, had left his tools in her care on his last shore leave. Petersen was at sea at the time of the murders, but his fellow lodger, John Williams, was said to have shaved off his whiskers the following day; furthermore, he had been seen washing his own stockings at the pump in the yard; and both he and another lodger, John Ritchen, knew Petersen. This was enough for an arrest. On 27 December the magistrates’ court was packed with eager spectators when the news came that Williams had committed suicide in his cell.

The immediate reaction was that the suicide was an outright confession. Anything that contradicted this comforting notion was pushed to one side. On reflection, the questions greatly outweighed the certainties. It was not even clear that John Williams’ name was John Williams – he had told the Vermiloes it was Murphy. Mr Vermiloe, the landlord, had been in prison for debt when his wife directed the police to Williams. The twenty-guinea reward for identifying the maul would pay off at least some of his debts, possibly all of them; how much weight could be given to her evidence? And two men at least had been at the Marrs’: the footprints of two men were found, and at least two men had been seen running down the road. Who were they? Vermiloe had used the maul to chop wood, and both it and the ripping chisel that was also found in the Marrs’ kitchen had been used as toys by his children in the yard – anyone could have taken them.

None of these questions was asked. Instead everyone agreed that they had long suspected Williams. One witness swore that, three weeks before the Williamsons were murdered, he had seen Williams with ‘a long French knife with an ivory handle’. No one else had ever seen that knife and Williams together, but the Gentleman’s Magazine reported that on 14 January 1812, miraculously, a lodger at the Pear Tree had found a blue jacket which he said had belonged to Williams, and it was reported that the inside pocket was marked, ‘as if a bloodstained hand had been thrust into it’. But bloodstains could not definitely be identified until the twentieth century – what the witness meant was that the stain was brown. Furthermore, no one else had seen Williams wear this jacket, nor was there any discussion about who might have had access to it during the period of the murders, or in the following month. Mrs Vermiloe turned it over to the police, at which point they returned to the Pear Tree, searched the house once more and found a clasp knife, ‘apparently dyed with blood’, hidden behind a wall. The Edinburgh Annual Register added that a pair of trousers had been found shoved down under the ‘soil’ in the privy in the Pear Tree yard, which ‘are spoken to very confidently by Williams’ fellow-lodgers’.

Half a century later, magazines were still reprinting these rumours, and creating new ones: ‘Williams was so notorious an infamous man, for all his oily and snaky duplicity, that the captain of his vessel, the Roxburgh Castle, had always predicted that. he would mount the gibbet.’ This comes from All the Year Round, Charles Dickens’ magazine, and Dickens was evidently fascinated by Williams, and in no doubt about his guilt. As well as commissioning this article, he owned an illustration of ‘the horrible creature’, and had also touched lightly on the subject in Dombey and Son (1847–48): when Captain Cuttle, who lives down by the docks, keeps his shutters closed one day, the neighbours speculate ‘that he lay murdered with a hammer, on the stairs’.

Meanwhile, the authorities had to decide how to respond to Williams’ death. Most immediately, they needed to show the local residents that he would not escape justice by his suicide. It would be another century before a British judge decreed that it is ‘of fundamental importance that justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done’, but the idea was already well understood. So on the last day of 1811, an inclined wooden platform was placed atop a high cart. Williams’ body was laid out on this, dressed in a clean white shirt (frilled, say some sources), blue trousers and brown stockings: in other words, in the neat, clean dress of a labouring man, although without a neck-handkerchief or hat, marks of decency and respectability. His right leg was manacled, as it would have been when he was in gaol. The maul was placed on one side of his head, the ripping chisel on the other.

At ten o’clock, a macabre and unprecedented procession set off at a stately walking pace. The head constable led the way, followed by

Several hundred constables, with their staves …

The newly-formed Patrole [sic], with drawn cutlasses.

Another body of Constables.

Parish Officers of St. George’s and St. Paul’s, and Shadwell, on horseback.

Peace Officers, on horseback, Constables.

The High Constable of the county of Middlesex, on horseback

THE BODY OF WILLIAMS …

A strong body of Constables brought up the rear.

Crowds lined the route; more watched from windows and even the rooftops. Shops were shut, blinds drawn as a mark of respect to the Marrs and the Williamsons. The cart travelled first to the Ratcliffe Highway, where it stood for a quarter of an hour outside the Marrs’ house. An enraged member of the public climbed onto the cart and forcibly turned Williams’ head towards the house, to ensure that the murderer was brought face to face with the scene of his crime. Then the procession travelled on to New Gravel Lane, where again the cart rested outside the death site. Finally it processed to Cannon Street, on the edge of the City, and paused again. Then a stake was driven through Williams’ heart (some reports say hammered home by the fatal maul), and his body was tumbled into a grave – some sources say a large one, so he could be tossed in; others that it was purposely made too small and shallow. Either way, the intention was to show deliberate disrespect. The crowd, which had so far watched in almost total silence, howled to see the last of the man who had killed seven people – half as many as had been murdered in the entire previous year throughout England and Wales.

This was not the last the world was to see of John Williams. Bodily, he reappeared in 1886, when workmen laying a gas pipe in what was now the heart of the City dug up a skeleton with a stake through its heart. Rumour later had it that at some point Williams’ skull appeared in the keeping of the publican ‘at the corner of Cable Street and Cannon Street Road’. In 1886 the Pall Mall Gazette further reported that Madame Tussaud’s waxworks had a ‘beautifully executed’ portrait of Williams, drawn from life by Sir Thomas Lawrence. But when precisely had Lawrence seen Williams? In the two days between his arrest and suicide? Or perhaps in his final, cart-top appearance?

Williams was to cast a longer shadow on the mental attitudes to crime and crime prevention in the nineteenth century than his skeletal remains could do physically. His ghost made several appearances in Parliament in the months that followed his death. The government was slower than the public to embrace the solution of Williams as the sole murderer. In a debate, the radical MP William Smith simply assumed that the crimes had been committed by ‘a gang of villains, of whom few or no traces had yet been discovered’. The Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, agreed with him.* The case ‘was still wrapped up in mystery. It undoubtedly seemed strange that a single individual could commit such accumulated violence.’

It was not the mystery that troubled the politicians; it was that policing throughout London was now seen to be completely inadequate. The city was still eighteen years away from establishing a centralized police force, and relied on a patchwork of overlapping organizations that had developed independently. By 1780 there were 800,000 inhabitants living in London’s two hundred parishes, which were responsible for the watch and policing, and also for lighting, waste disposal, street maintenance and care of the poor. But nothing was straightforward: Lambeth parish had nine trusts responsible for street lighting, St Pancras eighteen for paving; by 1800 there were fifty London trusts charged with maintaining the turnpike roads alone. In 1790, a thousand parish watchmen and constables were employed by seventy separate trusts. And even twenty years before that, in a city that was then much smaller, Sir John Fielding, the famous Bow Street magistrate, had warned Parliament that ‘the Watch. is in every Parish under the Direction of a separate Commission’, which left ‘the Frontiers of each Parish in a confused State, for that where one side of a street lies in one Parish, the Watchmen of one Side cannot lend any Assistance to [a] Person on the other Side, other than as a private Person, except in cases of Felony’.