Kitabı oku: «Agatha Christie: A Life in Theatre», sayfa 3

There can be no doubt that Saunders’ meticulous attention to detail, exemplary financial housekeeping and understanding of publicity in all its forms was instrumental in establishing Christie’s unassailable position as Queen of the West End in the 1950s. Without Saunders at the helm The Mousetrap may well not have run, and Christie would certainly never have penned her dramatic masterpiece Witness for the Prosecution. The former journalist, who was a relative newcomer to theatre when she first entrusted him with her work, became a lifelong friend and a frequent visitor to Greenway, the family home. In any event, the triumvirate of Cork, Harold Ober and Saunders proved an unstoppable force in ensuring the business success of Christie’s theatrical work. But Saunders, for all his achievements, carved his own niche in theatreland based largely on a profitable, populist repertoire rather than allying himself with the theatrical oligarchy of the day and their aspirations to educate audiences as well as to entertain.

The irony is that Christie herself didn’t need the money – her ‘day job’ took care of that – and it would have been interesting to see what history would have made of her as a playwright if she had persevered with some of her interesting early theatrical associations. The first Christie play to be produced was directed by a leading light of the Workers’ Theatre Movement, and her first West End hit was directed by the first woman to direct Shakespeare at Stratford and co-produced by a female producer and a co-operative founded by a leading Labour politician. The first ‘director’ Saunders introduced Christie to was Hubert Gregg, a comedy actor even less experienced in the role of director than Saunders himself was at the time in that of producer. The taxman might have been less happy if Christie had never met Saunders, but the chances are that theatre historians might have taken her work more seriously. And to me that is a poor reflection on theatre historians rather than on the resourceful, diligent and hard-working Saunders.

The combination of the Cork and Saunders archives furnishes a comprehensive backstage picture of the ‘Saunders years’, but although the British side of the operation prior to that is sparsely documented, the American side is not. Christie’s first Broadway venture as a playwright (a couple of third-party adaptations from her novels had preceded it) was an even bigger hit than it had been in London. The retitled Ten Little Indians was produced by the Shuberts, America’s leading theatrical producers of the day, in 1944. The company, set up by three brothers from Syracuse at the end of the nineteenth century, still flourishes; and their archive, located at the Lyceum Theatre on New York’s West 45th Street, in a splendid office complete with the brothers’ original furnishings and photographs, provides an unparalleled insight into American theatre history. As with Saunders’ archive, a wealth of original documentation has been retained, along with a well-resourced script library. It was the latter that took me to New York, on the trail of the only copies of a completely overlooked Christie script, which turned out to have been the only play of hers to receive its world premiere in America in her lifetime. Not only did I find exactly what I was looking for, but also a whole lot more …

The only other play of Christie’s to transfer to Broadway was an even bigger hit there: Witness for the Prosecution in 1954. By this time Saunders was at the helm in the UK, and he was not alone in finding the Shuberts frustrating to deal with. The more affable Gilbert Miller was therefore offered the licence to co-produce on Broadway, and while I was in New York unearthing the Christie treasures in the Shubert archive I also tracked down some of Miller’s papers, which resulted in a visit to the Library of Congress in Washington DC. Several other important theatrical archives in both the UK and the USA have assisted hugely in completing the picture of Agatha Christie, playwright from the ‘backstage’ perspective.

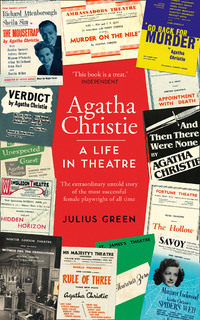

So, what is this book exactly? It is not a biography – if you want the story of Agatha’s childhood or her two marriages, or an analysis of how her life is reflected in some of her lesser-known works, then please look elsewhere. It is not about the ‘eleven missing days’, or ‘one missing night’, as I prefer to call it, since we know exactly where she was for the rest of the time. One of the ‘missing’ plays, I believe, may have some bearing on this over-reported episode; but you must draw your own conclusions, and my book will no doubt avoid the best-seller list by failing to come up with yet another ‘definitive’ new theory on the subject. It is not a literary analysis; there is no point at all in engaging in the long-running debate between the ‘highbrow’ and the ‘middlebrow’ when it comes to popular culture. I have neither the vocabulary nor the patience for it. Neither is it a ‘reader’s companion’. If you want to find out about the plots and the characters then I suggest you read the plays themselves or, better still, go and watch a production of them; and if you want to play ‘spot the difference’ between the novels and short stories and their adaptations then read the originals as well. This is not a book about Christie’s imaginary world, it is about the very real world of a playwright struggling to get her work produced, enduring huge disappointment and finally enjoying success on a scale that she could only have dreamt of. Because the playwright concerned happens to be female, it is unusual in not having been written by a feminist academic; as a theatre producer I have no agenda other than to set the record straight about Christie’s contribution to theatre on a number of levels. I am hoping that by offering more detail about what she achieved, particularly as an older woman in a male-dominated industry, working at a time of enormous social, political and cultural change, the value of her work for the theatre, over and above its purely monetary one, may come to be more widely acknowledged than it currently is.

To understand the unique trajectory of Christie’s playwriting career, it needs to be set within the theatrical history of the time. In Christie’s case this means charting a timeline from around 1908, when she made her first attempts at writing scripts, through to the last premiere of her work in 1972. In so doing, I will introduce a whole new cast of characters to the oft-told story of this extraordinary lady; the colourful and eccentric cast that populated Agatha Christie’s much-cherished world of theatre.

One thing that this book is definitely not about is detectives, and I am sorry if that disappoints some readers. But I have often felt like a detective myself as I have hunted down, assembled and analysed the evidence from a variety of different sources, and from often conflicting accounts of the same events. I hope that Hercule Poirot would have approved of my efforts and that what emerges is something approaching the truth behind the remarkable and previously untold story of Agatha Christie, playwright.

Act One

SCENE ONE

The Early Plays

Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller was fascinated by theatre from an early age. In sleepy, Victorian middle-class Torquay, ‘one of the great joys in life was the local theatre. We were all lovers of the theatre in my family,’ she writes in her autobiography. Older siblings Madge and Monty visited the Theatre Royal and Opera House in Abbey Road practically every week, and the young Agatha was usually allowed to accompany them. ‘As I grew older it became more and more frequent. We went to the pit stalls always – the pit itself was supposed to be “rough”. The pit cost a shilling and the pit stalls, which were two rows of seats in front, behind about ten rows of stalls, were where the Miller family sat, enjoying every kind of theatrical entertainment.’1 Clara and Frederick Miller clearly did everything they could to encourage this interest in their children, and Agatha was always captivated by the colourful dramas unfolding in front of her:

I don’t know whether it was the first play I saw, but certainly among the first was Hearts and Trumps, a roaring melodrama of the worst type. There was a villain in it, the wicked woman called Lady Winifred, and there was a beautiful girl who had been done out of a fortune. Revolvers were fired, and I clearly remember the last scene, when a young man hanging from a rope from the Alps cut the rope and died heroically to save either the girl he loved or the man whom the girl loved.

I remember going through this story point by point. ‘I suppose,’ I said, ‘that the really bad ones were Spades’ – father being a great whist player, I was always hearing talk of cards – ‘and the ones who weren’t quite so bad were Clubs. I think perhaps Lady Winifred was a Club – because she repented – and so did the man who cut the rope on the mountain. And the Diamonds’ – I reflected. ‘Just worldly,’ I said, in my Victorian tone of disapproval.2

The first story Agatha ever wrote took the form of a play, a melodrama concerning ‘the bloody Lady Agatha (bad) and the noble Lady Madge (good) and a plot that involved the inheritance of a castle’. Madge only agreed to take part in the production on condition the epithets were switched round. It was very short, ‘since both writing and spelling were a pain to me’, and amused her father greatly.3 Agatha’s parents often travelled, and when they did so she would stay in Ealing with great-aunt Margaret, who had been responsible for the upbringing of Agatha’s mother and was thus referred to by her as ‘Auntie-Grannie’. Even when Agatha was away from home, theatre ‘never stopped being a regular part of my life’, she recalls. ‘When staying at Ealing, Grannie used to take me to the theatre at least once a week, sometimes twice. We went to all the musical comedies, and she used to buy me the score afterwards. Those scores – how I enjoyed playing them!’4

The family spent some time in France during her childhood, and seven-year-old Agatha, inspired by the local pantomime in Torquay, began staging her own work for the enjoyment of her parents, using the window alcove in their bedroom as a stage, and assisted by her long-suffering young French chaperone, Marie. ‘Looking back, I am filled with gratitude for the extraordinary kindness of my father and mother. I can imagine nothing more boring than to come up every evening after dinner and sit for half an hour laughing and applauding whilst Marie and I strutted and postured in our home-improvised costumes. We went through the Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast and so forth.’5 Although young Agatha studied piano, dance and singing, and at one point had aspirations to become an opera singer, she appears to have gained the greatest fulfilment from her various youthful theatrical ventures, a natural progression from the dreamy childhood role-play games that, as a home-educated child, she created to pass the time.

The Christie archive contains a delightfully witty, meticulously handwritten twenty-six-page ‘acting charade in three acts’ called Antoinette’s Mistake, with a colourful hand-drawn cover that is clearly the work of a child. The play concerns the exploits of a French maid in the house of one Miss Letitia Dangerfield and her niece Rosy, and features characters called Colonel Mangoe and Major Chutnee. The closest handwriting match with that of family members is to Frederick’s, and I like to think that this piece was perhaps penned by Agatha’s father as a tribute to the long-suffering Marie (Antoinette?), whose performance in one of Agatha’s fairy tale dramatisations ‘convulsed my father with mirth’. Agatha’s father was a leading light of the local amateur dramatics, and it was perhaps in recognition of the enjoyment which this brought the family that she agreed, in later life, to become president of the Sinodun Players, an amateur group based in Wallingford where she owned a house. She received numerous such requests throughout her life, but the local amateur dramatics and the Detection Club were the only societies of which she accepted the presidency.

Frederick died aged fifty-five, when Agatha was eleven and both of her siblings had already left Ashfield, the family home in Torquay; but her mother continued to nourish young Agatha’s enthusiasm for theatre, whisking her off to see Irving perform in Exeter. ‘He may not live much longer, and you must see him,’ she insisted.6 Agatha herself, notoriously averse to public speaking in later life, enjoyed venturing onto the stage in her youth, and an ambitious production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Yeomen of the Guard, produced by a group of young friends at the Parish Rooms in Torquay, gave her the opportunity to show off her singing voice in the role of Colonel Fairfax. ‘As far as I remember I felt no stage fright … There is no doubt that The Yeomen of the Guard was one of the highlights of my existence.’7

Finishing school in Paris at the age of sixteen was an opportunity to sample the French capital’s theatrical delights. She enjoyed herself in drama class, and had a remarkable ability to appreciate a fine theatrical performance:

We were taken to the Comedie Francaise and I saw the classic dramas and several modern plays as well. I saw Sarah Bernhardt in what must have been one of the last roles of her career, as the golden pheasant in Rostand’s Chantecler. She was old, lame, feeble, and her golden voice was cracked but she was certainly a great actress – she held you with her impassioned emotion. Even more exciting than Sarah Bernhardt did I find Rejane. I saw her in a modern play, La Course aux Flambeaux. She had a wonderful power of making you feel, behind a hard repressed manner, the existence of a tide of feeling and emotion which she would never allow to come out in the open. I can still hear now, if I sit quiet a minute or two with my eyes closed, her voice, and see her face in the last words of the play: ‘Pour sauver ma fille, j’ai tué ma mere,’ and the deep thrill this sent through one as the curtain came down.8

After spending a ‘season’ as a seventeen year old in Cairo with her mother, Agatha found herself a regular guest on the house party circuit. This served its purpose of introducing her to a number of eligible young bachelors, and she also became friends with the colourful theatrical impresario C.B. Cochran and his devoted and long-suffering wife, Evelyn. Charles Cochran was indisputably the greatest showman of his generation, in a career that included productions of Ibsen alongside the promotion of boxing, circus and rodeo as well as the management of Houdini. He was also to be instrumental in launching the career of Noël Coward. That was still ahead of him when he met the young Agatha, but for one thing he could take credit. Cochran was responsible for introducing the rollerskating craze which swept the country in the early 1900s, and a famous photograph shows Agatha and her friends enjoying some skating on Torquay’s Princess Pier. The Cochrans eventually invited her to their house in London, where she was ‘thrilled by hearing so much theatrical gossip’.

As a young woman, Agatha continued her own forays onto the stage. Photographs show her and her friends gloriously costumed for The Blue Beard of Unhappiness, which the programme (printed on blue paper of course) reveals to be ‘A drama of Eastern domestic life in two acts’.9 An open air production with a dozen in the cast, it is, we are told, set on a part of the terrace in Blue Beard’s castle in ‘Bagdad’. The folktale of wife-murderer Bluebeard was to provide Agatha with inspiration on more than one later occasion. In the ‘Confessions Album’, in which members of the Miller family regularly made light-hearted entries listing their current likes and dislikes, a 1910 entry from Agatha nominates Bluebeard as one of two characters from history whom she most dislikes.10 The other is nineteenth-century Mormon leader Brigham Young, the founder of Salt Lake City: another extravagantly bearded polygamist, though in this case not a serial killer. ‘Why did they Bag-dad?’ asks The Blue Beard of Unhappiness’s programme, and goes on to state ‘Eggs, fruit and other Missiles are to be left with the Cloak Room Attendant’. No playwright is credited and, sadly, no script survives.

Many of Agatha’s earliest writings were in verse, and her first published dramatic work took this form. A Masque from Italy, originally written in her late teens, was later included (with the subtitle ‘The Comedy of the Arts’) in the 1925 self-published poetry volume Road of Dreams, and has thus been overlooked as a playscript. Although it is structured as a series of solo songs (which she set to music shortly before the book was published), the piece is clearly intended as a short theatrical presentation, as indicated by, the word ‘masque’ in its title, and may have been written as a puppet show. There is a cast list, consisting of six characters from Italian commedia dell’arte; and a clear dramatic through-line based on the love triangle between Harlequin, Pierrot and Columbine, delivered in a prologue, seven songs and an epilogue. Punchinello serves as a master of ceremonies and is here envisaged as a marionette rather than as the ‘Mr Punch’ glove puppet. We know that Agatha was intrigued by a Dresden China collection of these characters owned by her family, but the piece shows a thorough understanding of their traditional dramatic functions and motivations (apart from some ambiguity over a female counterpart of Punchinello), and it is more than possible that local pantomimes were still including a traditional Harlequinade sequence featuring them when she was in the audience as a child at the turn of the century. Her lifelong interest in the Harlequin figure, later to manifest itself in the Harley Quin short stories, is here informed by his role as the dangerous and exciting stranger stealing women’s hearts, which was to be a recurring theme in her early plays.

And when the fire burns low at night, and

Lightning flashes high!

Then guard your hearth, and hold your love,

For Harlequin goes by.11

The pain of lost love and the tensions between these passionate and flamboyant characters are well drawn, and with Harlequin in his ‘motley array’ and Punchinello inviting the audience to ‘touch my hump for luck’, the whole effect is deeply theatrical. Whether performed by puppets or people, it would have been fun to watch.

Encouraged by her mother, and perhaps in the hope of emulating her sister who had had some success with the publication of short stories in Vanity Fair, Agatha began writing stories in her late teens. ‘I found myself making up stories and acting the different parts and there’s nothing like boredom to make you write.’12 Adopting the pseudonyms Mac Miller, Nathaniel Miller and Sydney West, Agatha set about composing a number of short stories on her sister’s typewriter, but they failed to impress the editors of the magazines she sent them to.

‘Sydney West’ had a particularly idiosyncratic style, and was responsible for a short one-act play entitled The Conqueror which, like the short story ‘In the Market Place’, also authored by West, is a parable with a mythological flavour. The Ealing address of Agatha’s great-aunt is inked on the script, which does not list a dramatis personae. Subtitled ‘A Fantasy’, the scene is ‘a great Mountain overlooking the Earth. On a throne sits a huge, grey Sphinx like figure, veiled and motionless. Around her are Messengers of Fate, and the air is full of winged Destinies who come and go ceaselessly.’13 A blind youth ascends the mountain and exposes the Sphinx, who appears to represent Fate, as a sham. Like ‘In the Market Place’, the whole thing is rather baffling and appears to be some sort of morality tale. It is intriguing to imagine what future Agatha envisaged for this play, particularly given the practicalities of ‘winged destinies’. Though atmospheric, and not without its interest as a stylistic experiment, it is hard to imagine that it would have proved particularly popular with the local teams responsible for putting together Antoinette’s Mistake and The Blue Beard of Unhappiness. What this odd little offering does do, though, is once again confirm the broad range of Agatha’s theatrical vocabulary.

When eighteen-year-old Agatha produced her first novel, Snow Upon the Desert, her mother suggested that she send it to local author Eden Phillpotts for his comment. Phillpotts became Agatha’s valued mentor, and it was his literary agent Hughes Massie & Co. which, having rejected Snow Upon the Desert, would eventually take her under their wing fifteen years later, the imposing Massie himself having by then been succeeded by the more affable Edmund Cork.

A long-time neighbour of the Millers in Torquay – his daughter Adelaide attended the same ballet class as Agatha Eden Phillpotts was forty-six when he started advising Agatha, and already a successful novelist. A sort of Thomas Hardy of Dartmoor, specialising in work written in Devon dialect and set in Devon locations, his prolific output would eventually exceed even Agatha’s, and he enjoyed some success latterly with detective fiction. Well connected in literary circles – he had undertaken collaborations with Arnold Bennett and Jerome K. Jerome – Phillpotts had originally trained as an actor in London but had been forced to abandon his thespian aspirations due to a recurring illness that made him unable to control his legs. His love of the theatre never left him, though, and although he had experienced no great success as a playwright by the time he counselled Agatha, he went on to write some thirty plays, a number of which were notable and long-running West End successes.

In 1912 Phillpotts famously refused to concede to the request of the Lord Chamberlain’s office that he alter two lines in his play The Secret Woman, about a man who starts a relationship with his son’s lover, with the result that they refused to issue it with a licence. The ensuing furore saw many of the great writers of the day sign a letter to The Times in his support and contribute to a fund to enable performances to take place in a ‘club’ theatre where a licence was not required. Amongst the signatories was Bernard Shaw, whose work ‘in its massive and glittering magnificence’ Phillpotts admired greatly, in particular ‘the thousand challenges he offers to humanity on burning and still living questions’.14 Phillpotts and Shaw would later meet at Birmingham Repertory Theatre which, under its legendary founder Barry Jackson, regularly produced the work of both men. There can be no doubt that Phillpotts shared his enthusiasm for Shaw with the young Agatha and that this informed some of her early, unpublished playwriting ventures, which deal with such Shavian preoccupations as variations on the marriage contract, grounds for divorce and eugenics. The lengthy and witty preface to Shaw’s 1908 Getting Married has particular resonances in some of Christie’s early work.

In any event, contact with Phillpotts would have broadened young Agatha’s mind when it came to the issue of human relations, as is evidenced by his recommended reading for her. In a letter to her he suggests that she try ‘a few of the Frenchmen’, including Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. ‘But this last is very strong meat and perhaps you had better wait till you have taken some lighter dose first of the more modern men. When you come to it, remember that Madame Bovary is one of the greatest works in the world.’15 Although one may concur with his literary appraisal, Madame Bovary seems a particularly daring recommendation for an eighteen-year-old Edwardian girl, given its subject matter and the lifestyle of its author, who stood trial in France for obscenity in 1857 after it was published in a magazine.

Sadly, Phillpotts’ advocacy of unconventional human relations extended beyond literature and into his family life. His daughter Adelaide, who collaborated with him on a number of books and plays, including the 1926 Theatre Royal Haymarket success Yellow Sands – and whose literary career was to cross paths with Agatha’s in the future – was the long-term victim of his incestuous attentions, as is apparent from his correspondence with her and, indeed, her own autobiography.16 This bizarre obsession was confined to the one relationship, and there is no indication of any impropriety as far as the young Agatha was concerned. There can be no doubt that Phillpotts’ advice and input, and his role as a sounding board for her early work, was critical to Agatha’s blossoming as a writer, enabling her to gain confidence in her writing and widen her horizons. Indeed, her 1932 novel Peril at End House was dedicated to Phillpotts ‘for his friendship and the encouragement he gave me many years ago’. He doubtless, too, encouraged her interest in theatre, and they maintained a sporadic correspondence until the 1950s. In 1928 Phillpotts’ wife died and the following year he married a young cousin. We will hear more of Adelaide later.

Nobody would publish Agatha’s novel Snow Upon the Desert, but she carried on producing short stories and one-act plays. Amongst these, Teddy Bear is an endearing and performable comedy for two male and two female actors, written under the pseudonym of George Miller. A well-constructed but lightweight romp, it centres around young Virginia’s attempts to attract the attention of Ambrose Seaton, a fellow who is involved in an impressive array of charitable ventures:

VIRGINIA: He’s so good looking and – and so splendid. Look at all his philanthropic schemes, the Dustmen’s Christian Knowledge, and the Converted Convicts Club, and the Society for the Amelioration of Juvenile Criminals.17

Virginia eventually adopts a strategy of attracting Ambrose’s attention by herself becoming a ‘juvenile criminal’. Needless to say, things do not go according to plan, and after the farcical unravelling of her scheme she abandons her attempts to ensnare the virtuous but elusive (and possibly gay) Ambrose and settles instead for her long-suffering admirer, Edward:

EDWARD: You heard me say I wasn’t going to propose again?

VIRGINIA: (smiling) Yes.

EDWARD: (with dignity) Well, I’m not going to.

VIRGINIA: (laughing) Don’t.

EDWARD: Not in that sense. I was going to suggest a business arrangement.

VIRGINIA: Business?

EDWARD: You see, you’ve got a lot of money, and I’m badly in need of some. The simplest way for me to get it would be to marry you. See?

VIRGINIA: (still laughing) Quite.

EDWARD: No sentiment about it.

VIRGINIA: Not a scrap.

EDWARD: Well – what do you say?

VIRGINIA: (very softly) I say – yes.

EDWARD: Virginia! (tries to take her in his arms)

VIRGINIA: (springing up) Remember you’re only marrying me for the money …

This is nicely constructed comic banter, although there is already an undercurrent of more serious debates about the nature of the marriage contract. In this case, it all ends happily, although it is clear who the dominant force in the relationship is going to be:

VIRGINIA: (tragically) … a confession of weakness. I’ve fallen from the high pinnacle of my own self esteem. I fancied that I was strong enough to stand apart from the vulgar throng, that I was not as other women (sits upright) but I am beaten, I am but one of the crowd after all, (slowly) I have –

EDWARD: (breathlessly) Fallen in love?

VIRGINIA: (dramatically) No. Bought a Teddy Bear!

Eugenia and Eugenics, another of Agatha’s unpublished and unperformed early one-act plays housed at the Christie Archive, is a more ambitiously constructed comedy which explores a popular theme of the day. We are told that it is set in 1914, which may be either the present or the future, given that it deals with the repercussions of a fictitious piece of legislation. In 1905 Shaw’s Man and Superman had received its London premiere, with a plot that underlined his belief that women are the driving force in human procreation, and that the development of the species is dictated by their success in finding biologically (rather than socially or financially) suitable partners: a quest which essentially constitutes the ‘Life Force’. There can be no doubt that Agatha’s work was also informed by this philosophy, although by what route it reached her is unclear. ‘What are men anyway?’ asks Kait in the 1944 novel Death Comes as the End. ‘They are necessary to breed children, that is all. But the strength of the race is in the women.’18 This novel is set in ancient Egypt, but time and again we see in Christie’s plays examples of the weak male either dominated or rejected by the superior female.

Shaw’s take on the topic, which challenged received Darwinian theory, was just one aspect of a much wider debate about the subject of eugenics that was current at the time, leading to the first International Eugenics Conference, held in London in 1912. Although there were ethical issues from the outset with a philosophy that advocated the genetic improvement of humanity, this was well before the concept of breeding a ‘master race’ took on a much more sinister aspect. Whilst Christie seems at home with Shaw’s approach to the matter, her comedy both makes merciless fun of the wider philosophy’s advocates and touches on some other burning issues of the day. Faced with an upcoming new law that will enforce eugenic philosophy by allowing only the physically and mentally perfect to marry, Eugenia has taken herself to what she believes to be a eugenics clinic advertising perfect partners. Her maid, Stevens, accompanies her: