Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

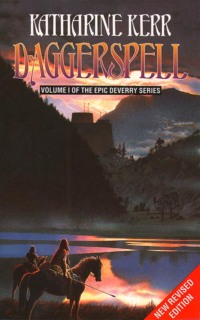

Kitabı oku: «Daggerspell»

KATHARINE KERR

Daggerspell

New revised edition

HISTORICAL NOTE

Many readers and reviewers have assumed that the Deverry books take place in some sort of alternate Britain or that the people of Deverry came originally from Britain. Since a few have even, in total defiance of geography, supposed that the series takes place on that island, I thought I’d best clarify the matter.

The Deverrians emigrated from northern Gaul, the “Gallia” referred to in the text, after they spent a fair number of years under the Roman yoke but before Christianity became a religion of any note. As for their new home, Annwn, the name is Welsh and literally means “no place,” a good clue, I should think, as to its location here in our world. Later volumes in this series explain how the original group of immigrants reached their new country and tell something of the history of their settlement.

COPYRIGHT

HarperVoyager an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Grafton Books 1987

Previously published in paperback by

HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993 (reprinted three times),

and by Grafton 1989 (reprinted seven times)

Copyright © Katharine Kerr 1986

Revised edition copyright © Katharine Kerr 1993

Katharine Kerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic ormechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007375981

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780008125295

Version: 2018-12-04

DEDICATION

For my husband, Howard,

who helped me more than even he can know.

Without his support and loving encouragement,

I never would have finished this book.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Pronunciation Notes

Prologue: In The Year 1045

Cerrgonney, 1052

Deverry, 643

Deverry, 1058

Deverry, 698

Eldidd, 1062

Eldidd, 1062

Glossary

Incarnations of The Various Characters

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

MAPS

PRONUNCIATION NOTES

The Deverrian language, which we might well call neo-Gaulish, looks and sounds much like Welsh, but anyone who knows this modern language will see immediately that it differs in a great many respects, as it does from Cornish and Breton. All these languages are members of that subfamily of Indo-European known as P-Celtic.

VOWELS are divided by Deverry scribes into two classes: noble and common. Nobles have two pronunciations; commons, one.

A as in father when long; a shorter version of the same sound, as in far, when short.

O as in bone when long; as in pot when short.

W as the oo in spook when long; as in roof when short.

Y as the i in machine when long; as the e in butter when short.

E as in pen.

I as in pin.

U as in pun.

Vowels are generally long in stressed syllables; short in unstressed. Y is the primary exception to this rule. When it appears as the last letter of a word, it is always long whether that syllable is stressed or not.

DIPHTHONGS generally have one consistent pronunciation.

AE as the a in mane.

AI as in aisle.

AU as the ow in how.

EO as a combination of eh and oh.

EW as in Welsh, a combination of eh and oo.

IE as in pier.

OE as the oy in boy.

UI as the North Welsh wy, a combination of oo and ee.

Note that OI is never a diphthong, but is two distinct sounds, as in Carnoic, (KAR-noh-ik).

CONSONANTS are mostly the same as in English, with these exceptions:

C is always hard as in cat.

G is always hard as in get.

DD is the voiced th as in thin or breathe, but the voicing is more pronounced than in English. It is opposed to TH, the unvoiced sound in breath. (This is the sound that the Greeks called the Celtic tau.)

R is heavily rolled.

RH is a voiceless R, approximately pronounced as if it were spelled hr in Deverry proper. In Eldidd, the sound is fast becoming indistinguishable from R.

DW, GW, and TW are single sounds, as in Gwendolen or twit.

Y is never a consonant.

I before a vowel at the beginning of a word is consonantal, as it is in the plural ending -ion, pronounced yawn.

DOUBLED CONSONANTS are both sounded clearly, unlike in English. Note, however, that DD is a single letter, not a doubled consonant.

ACCENT is generally on the penultimate syllable, but compound words and place names are often an exception to this rule.

I have used this system of transcription for the Bardekian and Elvish alphabets as well as the Deverrian, which is, of course, based on the Greek rather than the Roman model. On the whole, it works quite well for the Bardekian, at least. As for Elvish, in a work of this sort it would be ridiculous to resort to the elaborate apparatus by which scholars attempt to transcribe that most subtle and nuanced of tongues.

PROLOGUE

IN THE YEAR 1045

Men see life going from a dark to a darkness. The gods see life as a death…

The Secret Book of Cadwallon the Druid

In the hall of light, they reminded her of her destiny. There, all was light, a pulsing gold like the heart of a candle flame, filling eternity. The speakers were pillars of fire within the fiery light, and their words were sparks. They, the great Lords of Wyrd, had neither faces nor voices, because anything so human had long since been burned away by dwelling in the hall of light. She had no face or voice either, because she was weak, a little flicker of pale flame. But she heard them speak to her of destiny, her grave task to be done, her long road to ride, her burden that she must lift and willingly.

“Many deaths have led you to this turning,” they said to her. “It is time to take your Wyrd in your hands. You belong to the dweomer in your very soul. Will you remember?”

In the hall of light, there are no lies.

“I’ll try to remember,” she said. “I’ll do my best to remember the light.”

She felt them grow amused.

“You will be helped to remember. Go now. It is time for you to die and enter the darkness.”

When she began to kneel before them, to throw herself down before them, they rushed forward and forbade her. They knew that they were only servants of the one true light, paltry servants compared to the glory they served, the Light that shines beyond all gods.

When she entered the gray misty land, she wept, longing for the light. There, all was shifting fog, a thousand spirits and visions, and the speakers were like winds, tossing her with words. They wept with her at the fall that she must make into darkness. These spirits of wind had faces, and she realized that she, too, now had a face, because they were all human and far from the light. When they spoke to her of fleshly things, she remembered lust, the ecstasy of flesh pressed against flesh.

“But remember the light,” they whispered to her. “Cling to the light and follow the dweomer.”

The wind blew her down through the gray mist. All round her she felt lust, snapping like lightning in a summer storm. All at once, she remembered summer storms, rain on a fleshly face, cool dampness in the air, warm fires, and the taste of food in her mouth. The memories netted her like a little bird and pulled her down and down. She felt him, then, and his lust, a maleness that once she had loved, felt him close to her, very close, like a fire. His lust swept her down and down, round and round, like a dead leaf caught in a tiny whirlpool at a river’s edge. Then she remembered rivers, water sparkling under the sun. The light, she told herself, remember the light you swore to serve. Suddenly she was terrified: the task was very grave, she was very weak and human. She wanted to break free and return to the Light, but it was too late. The eddy of lust swept her round and round till she felt herself grow heavy, thick, and palpable.

There was darkness, warm and gentle, a dreaming water-darkness: the soft, safe prison of the womb.

In those days, down on the Eldidd coast stretched wild meadows, crisscrossed by tiny streams, where what farmers there were pastured their cattle without bothering to lay claim to the land. Since the meadows were a good place for an herbman to find new stock, old Nevyn went there regularly. He was a shabby man, with a shock of white hair that always needed combing, and dirty brown clothes that always needed mending, but there was something about the look in his ice-blue eyes that commanded respect, even from the noble-born lords. Everyone who met him remarked on his vigor, too, that even though his face was as wrinkled as old leather and his hands dark with frog spots, he strode around like a young prince. He never seemed to tire, either, as he traveled long miles on horseback with a mule behind him to tend the ills of the various poor folk in Eldidd province. A marvel he is, the farmers all said, a marvel and a half considering he must be near eighty. None knew the true marvel, that he was well over four hundred years old, and the greatest master of the dweomer that the kingdom had ever known.

That particular summer morning, Nevyn was out in the meadows to gather comfrey root, and the glove-finger white flowers danced on the skinny stems as he dug up the plants with a silver spade. The sun was so hot that he sat back on his heels and wiped his face on the old rag that passed for a handkerchief. It was then that he saw the omen. Out in the meadow, two larks broke cover with a heartbreaking beauty of song that was a battle cry. Two males swept up, circling and chasing each other. Yet even as they fought, the female who was their prize rose from the grass and flew indifferently away. With a cold clutch of dweomer knowledge, Nevyn knew that soon he would be watching two men fight over a woman that neither could rightfully have.

She had been reborn.

Somewhere in the kingdom, she was a new babe, lying in her exhausted mother’s arms. On a mirror made of sky he saw it with his dweomer sight.

In a sunny room a midwife stood washing her hands in a basin. On a bed of straw and rags lay a pretty young lass, the mother, her face bathed in sweat from the birth but smiling at a child at her breast. As Nevyn’s sight showed him the baby, the tiny creature, all damp and red, opened cloudy blue eyes and seemed to stare right at him.

Nevyn jumped to his feet in sheer excitement. The Lords of Wyrd had been kind. This time they were sending him a warning that somewhere she was waiting for him to bring her to the dweomer, somewhere in the vast expanse of the kingdom of Deverry. He could search and find her while she was still a child, before harsh circumstances made it impossible for him to untangle the snarl of their intertwined destinies. This time, perhaps, she would remember and listen to him. Perhaps. If he found her.

CERRGONNEY, 1052

The young fool tells his master that he will suffer to gain the dweomer. Why is he a fool? Because the dweomer has already made him pay and pay and pay again before he even stood on its doorstep…

The Secret Book of Cadwallon the Druid

A cold drizzle of rain fell. The last of the twilight was closing in like gray steel. Looking at the sky made Jill frightened to be outside. She hurried to the woodpile and began to grab firewood. A gray gnome, all spindly legs and long nose, perched on a big log and picked at its teeth while it watched her. When she dropped a stick, it snatched it and refused to give it back.

“Beast!” Jill snapped. “Then keep it!”

At her anger, the gnome vanished with a puff of cold air. Half in tears, Jill hurried across the muddy yard to the circular stone building, a tavern, where cracks of light gleamed around wooden shutters. Clutching her firewood, she ran down the corridor to the chamber and slipped in, hesitating a moment at the door. The priestess in her long black robe was kneeling by Mama’s bed. When she looked up, Jill saw the blue tattoo of the crescent moon that covered half her face.

“Put some wood on the fire now, child. I need more light.”

Jill picked out the thinnest, pitchiest sticks and fed them into the fire burning in the hearth. The flames sprang up, sending flares and shadows dancing round the room. Jill sat down on the straw-covered floor in a corner to watch the priestess. On her pallet Mama lay very still, her face deadly pale, oozing drops of sweat from the fever. The priestess picked up a silver jar and helped Mama drink the herb water in it. Mama was coughing so hard that she couldn’t keep the water down.

Jill grabbed her rag doll and held her tight. She wished that Heledd was real, and that she’d cry so Jill could be very brave and comfort her. The priestess set the silver jar down, wiped Mama’s face, then began to pray, whispering the words in the ancient holy tongue that only priests and priestesses knew. Jill prayed, too, in her mind, begging the Holy Goddess of the Moon to let her mama live.

Macyn came to the doorway and stood watching, his thick pudding face set in concern, his blunt hands twisting the hem of his heavy linen overshirt. Macyn owned this tavern, where Mama worked as a serving lass, and let her and Jill live in this chamber out of simple kindness to a woman with a bastard child to support. He reached up and rubbed the bald spot in the middle of his gray hair while he waited for the priestess to finish praying.

“How is she?” Macyn said.

The priestess looked at him, then pointedly at Jill.

“You can say it,” Jill burst out. “I know she’s going to die.”

“Do you, lass?” The priestess turned to Macyn. “Here, does she have a father?”

“Of a sort. He’s a silver dagger, you see, and he rides this way every now and then to give them what coin he can. It’s been a good long while since the last time.”

The priestess sighed in a hiss of irritation.

“I’ll keep feeding the lass,” Macyn went on. “Jill’s always done a bit of work around the place, and ye gods, I wouldn’t throw her out into the street to starve, anyway.”

“Well and good, then.” The priestess held out her hand to Jill. “How old are you?”

“Seven, Your Holiness.”

“Well, now, that’s very young, but you’ll have to be brave, just like a warrior. Your father’s a warrior, isn’t he?”

“He is. A great warrior.”

“Then you’ll have to be as brave as he’d want you to be. Come say farewell to your mama; then let Macyn take you out.”

When Jill came to the bedside, Mama was awake, but her eyes were red, swollen, and cloudy, as if she didn’t really see her daughter standing there.

“Jill?” Mama was gasping for breath. “Mind what Macco tells you.”

“I will. Promise.”

Mama turned her head away and stared at the wall.

“Cullyn,” she whispered.

Cullyn was Da’s name. Jill wished he was there; she had never wished for anything so much in her life. Macyn picked Jill up, doll and all, and carried her from the chamber. As the door closed, Jill twisted round and caught a glimpse of the priestess, kneeling to pray.

Since no one wanted to come to a tavern with fever in the back room, the big half-round of the alehouse stood empty, the wooden tables forlorn in the dim firelight. Macyn sat Jill down near the fire, then went to get her something to eat. Just behind her stood a stack of ale barrels, laced with particularly dark shadows. Jill was suddenly sure that Death was hiding behind them. She made herself turn around and look, because Da always said a warrior should look Death in the face. She found nothing. Macyn brought her a plate of bread and honey and a wooden cup of milk. When Jill tried to eat, the food turned dry and sour in her mouth. With a sigh, Macyn rubbed his bald spot.

“Well now,” he said. “Maybe your da will ride our way soon.”

“I hope so.”

Macyn had a long swallow of ale from his pewter tankard.

“Does your doll want a sip of milk?” he said.

“She doesn’t. She’s just rags.”

Then they heard the priestess, chanting a long sobbing note, keening for the soul of the dead. Jill tried to make herself feel brave, then laid her head on the table and sobbed aloud.

They buried Mama out in the sacred oak grove behind the village. For a week, Jill went every morning to cry beside the grave till Macyn finally told her that visiting the grave was like pouring oil on a fire—she would never put her grief out by doing it. Since Mama had told her to mind what he said, Jill stopped going. When custom picked up again in the tavern, she was busy enough to keep from thinking about Mama, except of course at night. Local people came in to gossip, farmers stopped by on market day, and every now and then merchants and peddlers paid to sleep on the floor for want of a proper inn in the village. Jill washed tankards, ran errands, and helped serve ale when the tavern was crowded. Whenever a man from out of town came through, Jill would ask him if he’d ever heard of her father, Cullyn of Cerrmor, the silver dagger. No one ever had any news at all.

The village was in the northernmost province of the kingdom of Deverry, the greatest kingdom in the whole world of Annwn—or so Jill had always been told. She knew that down to the south was the splendid city of Dun Deverry, where the High King lived in an enormous place. Bobyr, however, where Jill had spent her whole life, had about fifty round houses, made of rough slabs of flint packed with earth to keep the wind out of the walls. On the side of a steep Cerrgonney hill, they clung to narrow twisted streets so that the village looked like a handful of boulders thrown among a stand of straggly pine trees. In narrow valleys farmers wrestled fields out of rocky land and walled their plots with the stone.

About a mile away stood the dun, or fort, of Lord Melyn, to whom the village owed fealty. Jill had always been told that it was everyone’s Wyrd to do what the noble-born said, because the gods had made them noble. The dun was certainly impressive enough to Jill’s way of thinking to have had some divine aid behind it. It rose on the top of the highest hill, surrounded by both a ring of earthworks and a ramparted stone wall. A broch, a round tower of slabbed stone, stood in the middle and loomed over the other buildings inside the walls. From the top of the village, Jill could see the dun and Lord Melyn’s blue banner flapping on the broch.

Much more rarely Jill saw Lord Melyn himself; who only occasionally rode into the village, usually to administer a judgment on someone who’d broken the law. When, on a particularly hot and airless day, Lord Melyn actually came into the tavern for some ale, it was an important event. Although the lord had thin gray hair, a florid face, and a paunch, he was an impressive man, standing ramrod straight and striding in like the warrior he was. With him were two young men from his warband, because a noble lord never went anywhere alone. Jill ran her hands through her messy hair and made the lord a curtsy. Macyn came hurrying with his hands full of tankards; he set them down and made the lord a bow.

“Cursed hot day,” Lord Melyn said.

“It is, my lord,” Macyn stammered.

“Pretty child,” Lord Melyn glanced at Jill. “Your granddaughter?”

“She’s not, my lord, but the child of the lass who used to work here for me.”

“She died of a fever,” one of the riders interrupted. “Wretched sad thing.”

“Who’s her father?” Lord Melyn said. “Or does anyone even know?”

“Oh, not a doubt in the world, my lord,” the rider answered with an unpleasant grin. “Cullyn of Cerrmor, and no man would have dared to trifle with his wench.”

“True enough.” Lord Melyn paused for a laugh. “So, lass, you’ve got a famous father, do you?”

“I do?”

Lord Melyn laughed again.

“Well, no doubt a warrior’s glory doesn’t mean much to a little lass, but your da’s the greatest swordsman in all Deverry, silver dagger or no.” The lord reached into the leather pouch at his belt and brought out some coppers to pay Macyn, then handed Jill a silver. “Here, child, without a mother you’ll need a bit of coin to get a new dress.”

“My humble thanks, my lord.” As she made him a curtsy, Jill realized that her dress was indeed awfully shabby. “May the gods bless you.”

After the lord and his men left the tavern, Jill put her silver piece into a little wooden box in her chamber. At first, looking at it gleaming in the box made her feel like a rich lady herself; then all at once she realized that his lordship had just given her charity. Without that coin, she wouldn’t be able to get a new dress, just as without Macyn’s kindness, she would have nothing to eat and nowhere to sleep. The thought seemed to burn in her mind. Blindly she ran outside to the stand of trees behind the tavern and threw herself onto the shady grass. When she called out to them, the Wildfolk came—her favorite gray gnome, a pair of warty blue fellows with long, pointed teeth, and a sprite, who would have seemed a beautiful woman in miniature if it weren’t for her eyes, wide, slit like a cat’s and utterly mindless. Jill sat up to let the gray gnome climb into her lap.

“I wish you could talk. If some evil thing should happen to Macyn, could I come live in the woods with your folk?”

The gnome idly scratched his armpit while he considered.

“I mean, you could show me how to find things to eat, and how to keep warm when it snows.”

The gnome nodded in a way that seemed to mean yes, but it was always hard to tell what the Wildfolk meant. Jill didn’t even know who or what they were. Although they suddenly appeared and vanished at will, they felt real enough when you touched them, and they could pick up things and drink the milk that Jill set out for them at night. Thinking of living with them in the woods was as much frightening as it was comforting.

“Well, I hope nothing happens to Macco, but I worry.”

The gnome nodded and patted her arm with a skinny, twisted hand. Since the other children in the village made fun of Jill for being a bastard, the Wildfolk were the only real friends she had.

“Jill?” Macyn was calling her from the tavern yard. “Time to come in and help cook dinner.”

“I’ve got to go. I’ll give you milk tonight.”

They all laughed, dancing in a little circle around her feet, then vanishing without a trace. As Jill walked back, Macyn came to meet her.

“Who were you talking to out here?” he said.

“No one. Just talking.”

“To the Wildfolk, I suppose?”

Jill merely shrugged. She’d learned very early that nobody believed her when she told them that she could see the Wildfolk.

“I’ve got a nice bit of pork for our dinner,” Macyn went on. “We’d best eat quickly, because on a hot night like this, everyone’s going to come for a bit of ale.”

Macyn proved right. As soon as the sun went down, the room filled with local people, men and women both, come to have a good gossip. No one in Bobyr had much real money; Macyn kept track of what everyone owed him on a wooden plank. When there were enough charcoal dots under someone’s mark, Macyn would get food or cloth or shoes from that person and start keeping track all over again. They did earn a few coppers that night from a wandering peddler, who carried round a big pack, holding fancy thread for embroidery, needles, and even some ribands from a town to the west. When Jill served him, she asked, as usual, if he’d ever heard of Cullyn of Cerrmor.

“Heard of him? I just saw him, lass, about a fortnight ago.”

Jill’s heart started pounding.

“Where?”

“Up in Gwingedd. There’s somewhat of a war on, two lords and one of their rotten blood feuds, which is why, I don’t mind telling you, I traveled down this southern way. But I was drinking in a tavern my last night there, and I see this lad with a silver dagger in his belt. That’s Cullyn of Cerrmor, a fellow says to me, and don’t you never cross him, neither.” He shook his head dolefully. “Them silver daggers is all a bad lot.”

“Now here! He’s my da!”

“Oh, is he now? Well, what harsh Wyrd you’ve got for such a little lass—a silver dagger for a da.”

Although Jill felt her face flush hot, she knew that no use lay in arguing. Everyone despised silver daggers. While most warriors lived in the dun of a noble lord and served him as part of his honor-sworn warband, silver daggers traveled round the kingdom and fought for any lord who had the coin to hire them. Sometimes when Da rode to see Jill and her mother, he would have lots of money to give them; at others, barely a copper, all depending on how much he could loot from a battlefield. Although Jill didn’t understand why, she knew that once a man became a silver dagger, no one would ever let him be anything else. Cullyn had never had the chance to marry her mother and take her to live with him in a dun, the way honor-sworn warriors could do with their women.

That night Jill prayed to the Goddess of the Moon to keep her father safe in the Gwingedd war. Almost as an afterthought, she asked the Moon to let the war be over soon, so that Cullyn could come see her right away. Apparently, though, wars were under the jurisdiction of some other god, because it was two months before Jill had the dream. Every now and then, she would dream in a way that was exceptionally vivid and realistic. Those dreams always came true. Just as with the Wildfolk, she had learned early to keep her true dreams to herself. In this particular one, she saw Cullyn come riding into town.

Jill woke in a fever of excitement. Judging from the short shadows that everything had in the dream, Da would arrive round noon. All morning Jill worked as hard as she could to make the time pass faster. Finally, she ran to the front door of the tavern and stood there looking out. The sun was almost directly overhead when she saw Cullyn, leading a big chestnut warhorse up the narrow street. All at once Jill remembered that he didn’t know about Mama. She dodged back inside fast.

“Macco! Da’s coming! Who’s going to tell him?”

“Oh, by the hells!” Macyn ran for the door. “Wait here.”

Jill tried to stay inside, but she grew painfully aware that the men sitting at one table were pitying her. Their expressions made her remember the night when Mama died so vividly that she ran out the door. Just down the street Macyn stood talking to her father with a sympathetic hand on his shoulder. Da was staring at the ground, his face set and grim, saying not a word.

Cullyn of Cerrmor stood well over six feet tall, warrior-straight and heavy-shouldered, with blond hair and ice-blue eyes. Down his left cheek ran an old scar, which made him look frightening even when he smiled. His plain linen shirt was filthy from the road, and so were his brigga, the loose woolen trousers that all Deverry men wore. On his heavy belt hung his one splendor—and his shame—the silver dagger in a tattered leather sheath. The silver pommel with its three little knobs gleamed, as if warning people against its owner. When Macyn finished talking, Cullyn laid his hand on his sword hilt. Macyn took the horse’s reins, and they walked up to the tavern.

Jill ran to Cullyn and threw herself into his arms. He picked her up, holding her tightly. He smelled of sweat and horses, the comforting familiar scent of her beloved da.

“My poor little lass!” Cullyn said. “By the hells, what a rotten father you’ve got!”

Jill wept too hard to speak. Cullyn carried her into the tavern and sat down with her in his lap at a table near the door. The men at the far table set down their tankards and looked at him with cold, hard eyes.

“You know what, Da?” Jill sniveled. “The last thing Mama said was your name.”

Cullyn tossed his head back and keened, a long, low howl of mourning. Hovering nearby, Macyn risked patting his shoulder.

“Here, lad,” Macyn said. “Here, now.”

Cullyn kept keening, one long moan after another, even though Macyn kept patting his shoulder and saying “here now” in a helpless voice. The other men walked over, and Jill hated their tight little smiles, as if they were taunting her da for his grief. All at once, Cullyn realized that they were there. He slipped Jill off his lap, and as he stood up, his sword leapt into his hand as if by dweomer.

“And why shouldn’t I mourn her? She was as decent a woman as the Queen herself, no matter what you pack of dogs thought of her. Is there anyone in this stinking village who wants to say otherwise to my face?”