Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

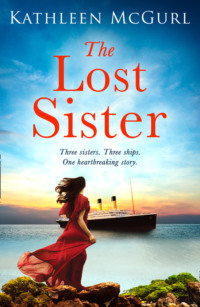

Kitabı oku: «The Lost Sister», sayfa 2

Chapter 2

Emma, 1911

Emma Higgins’ earliest memory was of being on board a ship. Well, it was not really a ship, she supposed. It was a ferry, a steamer operating between Southampton and Cowes, on the Isle of Wight. She’d been about four years old, her sister Ruby just a babe in arms and her sister Lily not yet born. She’d been so very excited to be on board a boat, amazed that such a huge thing could float, and astounded at the views from the deck as Southampton faded into the distance and Cowes loomed ever closer.

The family were on the ferry because they were moving to the Isle of Wight, where Emma’s father, George, had secured a job working in a new hotel in the fashionable resort of Sandown. ‘There’ll be a beach for you to play on,’ he’d told Emma, ‘and the sea for you to paddle in. We shall have a wonderful life in Sandown!’ But it was the sea crossing – steaming down Southampton Water and then across the Solent – that had captured little Emma’s imagination. When she looked back on it, she thought that was probably the moment that determined her lifelong fascination with being at sea.

They had lived in Sandown, George working in the hotel and Emma’s mother Amelia taking in sewing, for almost ten years, until George had fallen prey to a gang of ruffians one stormy afternoon when he had been carrying the hotel’s takings to the bank to lodge. They’d beaten him and stolen the money, leaving him lying in a ditch with broken ribs and a smashed skull. He was found some hours later by a passing policeman but did not recover from his injuries. Amelia, on hearing the news, had collapsed and taken to her bed for a week, by which time the rent was due and there was not enough money to pay it.

Emma’s second sea crossing, therefore, was the return trip from Cowes to Southampton, where the now-fatherless family stayed for a while with Amelia’s sister until Amelia felt able to leave her bed, take on work as a laundress and seamstress, and move herself and her daughters into a tiny terraced house near the Southampton docks.

Now, as Emma hurried back to that same terraced house, bursting with her news, she wondered what her mother and sisters would make of what she had to tell them. Would they be pleased? Or fearful? She had no idea. All she knew was that this felt like her destiny. A chance to go to sea again – properly to sea! – and actually live on board a ship. It felt so right. It seemed like a job that had her name on it; a job she’d been meant to do since she was four years old and had marched onto the bridge of the paddle steamer on the way to Cowes, demanding to see the horses that powered the ship. Her father had been simultaneously mortified and delighted by her audacity, she recalled, and the ferry’s skipper had picked her up and let her hold the wheel for one brief, glorious moment.

She turned a corner, passed the small grocery shop where Ma went every day to buy the family’s dinner, waved to the little girl who lived across the street and was playing out with a hoop and stick, and found herself running the last few yards to her front doorstep, where she almost tripped over her sister.

‘What are you doing sitting out here, Ruby? You’ll make your skirts all dirty and Ma’ll be furious.’

‘Huh. I scrubbed the step this morning so it’s clean as anything. Sitting out here because it’s better than being in there.’ Ruby pointed over her shoulder with her thumb at the house.

‘Oh dear. What’s happened now?’ Emma sighed. Her news would have to wait a while. She nudged Ruby with her foot to make her move over, and sat beside her.

‘Ma. That’s what’s happened. Making me scrub steps and wash clothes and sweep floors. I ain’t a general skivvy, Ems.’

‘We need to share out the jobs. Especially when Lily’s ill and Ma needs to nurse her.’

‘Where was you, then? Where was you this afternoon? You could have done your share of the jobs.’ Ruby glared at Emma. ‘I do enough blinking work at the hotel every morning without having to do more when I come back home.’

‘I swept upstairs and did all the grates this morning before I went out. While you were still abed,’ Emma replied. Part of her wanted to be furious at Ruby for suggesting she, Emma, didn’t do her fair share of the chores. But another part felt for her sister. Of course Ruby wanted more from life than to spend her days scrubbing floors. At 17 she deserved fun and happiness and sunshine and laughter. But with their father dead, their mother’s fading eyesight meaning she was struggling to sew her piecework, their little sister Lily’s precarious health requiring her to frequently spend days in bed … well, it was essential that Emma and Ruby have jobs and bring in some money. They’d both worked since leaving school at 14.

‘Yes, I know.’ Ruby leaned against Emma as a gesture of apology, and Emma smiled to show it was accepted. ‘But I wish there were some way out of this. Where’s my knight, riding over the horizon on his glossy black steed, come to sweep me off my feet and take me to his castle to live in luxury?’

Emma laughed. ‘You’ve been reading too many romances, Ruby. Life’s not like that.’

‘I know. I just wants something a bit different. Less scrubbing, more love and laughter with some lovely-looking fellow.’

‘You’re so pretty, Ruby, it’ll happen in time. You’re still young.’

‘Wish it would hurry up and happen.’

‘Ah, pet. Don’t wish your life away. Come on. Let’s go inside and make tea for us all. I have some news to share.’ Emma stood and held out her hand to haul her sister to her feet. Ruby followed her in, looking curious as Emma called for Ma and Lily to come to the kitchen and listen to what she had to say. As she passed through the hallway it dawned on her that her news would mean Ruby would have more work to do at home, as Emma wouldn’t always be there. With a pang of anxiety she wondered how her sister would take the news.

‘There’s a possibility of me getting a new job,’ Emma announced, when Ma, Ruby, and Lily were all sitting at the kitchen table, looking at her expectantly.

‘What, on top of the one you already have, in the Star Hotel?’ Ma looked surprised. Emma already worked six days a week cleaning hotel rooms.

Emma shook her head. ‘Instead of it. I wouldn’t be able to do both – listen while I tell you.’

‘Get on with it, then,’ Ruby said, rolling her eyes.

‘There’s a new ship coming in, next month. A big one. The biggest ever built, they say. It’s sailing down here from Liverpool, and then a week or so later it’s off on its first proper trip – the maiden voyage, they call it.’

‘So what?’ Ruby shrugged.

‘You want to get a job on it?’ Lily said, her eyes shining. ‘Will you be climbing the rigging?’

Emma laughed. ‘You’re right, Lils, I do want to work on it. But not on the rigging. She’s a steamship. An ocean liner. Her name is RMS Olympic.’

‘You, work on a ship?’ Ma said. ‘Doing what?’

‘As a stewardess, I hope. Looking after the rich people in their cabins. Or cleaning if I can’t get a stewardess job. Or in the kitchens.’

Lily looked vaguely disappointed that Emma wouldn’t be climbing the rigging. ‘Do you work on the ship when it sails away or only when it is in port?’

‘When it sails, dear Lily. The staff need to go on board before the passengers to make everything ready, and then stay on board as it sails across the ocean. All the way to New York, imagine that!’ Emma could barely imagine it herself. New York seemed so far away, but here was a chance that she might actually go there, herself, on board the world’s newest and largest ocean liner.

‘How can it go so far in a day?’ Lily still looked confused.

‘It doesn’t,’ explained Emma. ‘It takes many days to get there. But they think the Olympic might be able to beat the record and make the crossing faster than any ship ever has done before.’

‘Never mind about records and speed and whatnot. How are you going to get a job on board, I wants to know?’ questioned Ruby.

‘There’s interviews for posts on board starting next week, down at the docks. At the White Star Line’s shipping office. I have the right experience, and they need loads of people. I think I stand a good chance. And if they like me, I then sign on for the first voyage, and after that … well, who knows?’

‘How long would you be away for?’

‘About three weeks I think, for the first voyage, and then if I like the work and sign on for another, I’d be away again.’

‘Ems, don’t go! I’ll miss you!’ Lily climbed off her chair and clung to her big sister.

Emma wrapped an arm around Lily’s waist. ‘Ah now, pet. Just think of all the stories I’ll have to tell you when I come back! Three weeks would go by so quickly, and then I’d be home on leave for a few days or a week, before sailing again. You’re almost grown up now. And you’d still have Ma and Ruby here.’

‘Huh. Yes. Leave me with all the work, why don’t you? What if I runs off and gets a job on this ship as well, eh? What then?’ Ruby put her hands on her hips and glared at Emma.

‘Ruby, you need to be over 18 or they won’t employ you. But maybe next year …’

A thoughtful expression flitted across Ruby’s face, and Emma smiled. Her sister was always looking for more from life, adventure, something out of the ordinary, and this just might be the perfect solution. Let her, Emma, work on board ship first to find out what it was like, then if Ruby still liked the idea next year perhaps they could work together on board the Olympic or some other ship.

‘Well, I think it’s a marvellous idea,’ Ma said. ‘Is the pay good?’

‘Better than I am getting now, plus of course board and lodging is included. I’ll be able to save nearly all my pay and bring it home to you, Ma.’

‘Oh, no you won’t. Your pay is your pay. All I will need is a tiny bit to cover your food when you’re back home, and the rest is your own. You earn it, you keep it, lovey.’ Ma nodded decisively and folded her arms across her chest.

Emma smiled. One way or another she’d get her mother to accept some of her earnings, when the time came. The family needed it. ‘So is it all right? May I apply for a job on the ship? You don’t mind?’

‘I don’t mind at all, lovey,’ Ma said.

‘I mind.’ Ruby glared at Emma. ‘With you away for weeks on end I’ll have to do your share of the housework as well as my own, as well as my job. I’ll have no free time to myself. But you don’t care about that, do you?’

‘I can do Emma’s chores,’ Lily said. ‘I’m old enough now.’

‘Huh. Half the time you’re too poorly to help with anything. And with Emma away I’ll end up having to nurse you on top of everything else.’

Lily pouted. Emma sighed. It was true that she tended to be the one who looked after Lily most whenever she had one of her frequent bouts of ill health that had plagued her since she’d had tuberculosis at the age of seven. Ruby had always done the minimum.

‘Lily’s not so often sick these days, Rubes. Not now she’s growing up. It’ll be all right, if I go away, I’m sure. And I’d be back every few weeks.’ And it’s my chance to do something different with my life, she wanted to add. My life, my choice.

‘Of course it will be,’ Ma said. ‘Now then, how about a nice cup of tea? I hope they’ll have tea on board the ship. I know how much you like a cup in the mornings.’

‘Of course they’ll have tea,’ Emma said. ‘And I’m sure I’ll get a few breaks in the day in which I can drink a cup. At least I hope so!’

‘When are the interviews?’ Ruby wanted to know.

‘Tomorrow. I have a half day, so I’ll go down in the afternoon. Wish me luck!’

‘Good luck, lovey.’ Ma smiled but there was a sadness in her eyes. Her first daughter to leave home, even if it was only for temporary periods. But Emma knew Ma would miss her. As Emma was the eldest, Ma had leaned on her heavily since Pa had died. She’d helped nurse Lily. She’d counselled Ruby many times, doing her best to curb her middle sister’s wayward nature and spare her mother’s grey hairs. She’d taken on as much of the day-to-day housework and cooking in the home as she could. She’d been working in the Star Hotel since they’d returned from the Isle of Wight when she was 14, giving up most of her wages to help keep the family. None of it was what she’d dreamed of, but it was her duty as the eldest to take care of the family. And now, there was a chance to have some adventures of her own, while still helping provide for the family’s needs. It was perfect. If only she could get the job!

The following afternoon Emma changed quickly out of her work uniform, put on a neat brown dress and re-pinned her hair, then hurried down to the docks to the shipping offices of the White Star Line. There were people milling about everywhere; she had expected it to be busy and indeed there were hundreds of people, mostly men, hanging around in and outside of the offices. Emma approached a young woman who was waiting patiently inside the offices, sitting on a plain wooden bench that ran along one side. The woman, pretty with dark hair, was neatly dressed in a tweed coat and hat.

‘Hello,’ Emma said. ‘Do you mind if I sit with you? Am I in the right place for interviews for a job on RMS Olympic?’

The other woman smiled. ‘Of course, sit down. Yes, this is the right place to sign on. Is this your first time?’

Emma nodded. ‘I heard about the possibility of work and thought I would quite like it. I’m Emma Higgins, by the way.’ She held out her hand for the other woman to shake.

‘Violet Jessop. Good to meet you, Emma. Stick with me and I’ll help you out.’ She looked kindly at Emma, who felt relieved to have found a friend so quickly.

‘Have you done this before? Been to sea, I mean?’ Emma asked.

Violet nodded. ‘Several times, yes. I’ve been with White Star for a while and they asked me to come and sign on for the Olympic. But they’re short so they are needing to recruit more.’

‘All those men out there? Are they all trying for jobs?’

‘Some of them will be signing on, yes. As engineers, stokers, crew, able-bodied seamen, stewards, deckhands. There’s a lot more jobs for men than women. But they need stewardesses too to help look after the female passengers. That’s what I do. Is it what you are hoping for?’

‘Yes. I’ve been working in a hotel for a few years,’ Emma replied, as she looked around at the people milling about in the waiting area. ‘Should I be giving my name or something?’

‘Oh, heavens, have you not done that? Yes, go over there and give your name to the clerk at that desk.’ Violet gestured to where a man with greased-down hair was sitting behind a desk, fending off enquiries from several men at once.

Emma felt nervous as she approached. Some of the men looked rough – they must be hoping for work as stokers or engineers rather than as stewards. The man at the desk looked up at her.

‘Can I help?’

‘My name is Emma Higgins. I am looking for work as a stewardess, please.’

‘Very well, Miss Higgins, I’ll put your name down and if you can just wait over there until you’re called.’ He gestured to the bench where Violet was still sitting, and Emma returned to her seat gratefully.

A few minutes later a door opened, and a man in a smart suit came out and nodded to Violet. ‘You’re next, Vi,’ he said. ‘Glad to see you’ll be joining us on board.’ He tipped his hat to Emma and sauntered out, whistling.

‘Good luck getting the job,’ Violet said to Emma as she stood up. ‘Hope to see you when Olympic sails.’ She went through the door the man had left open and closed it behind her. Emma felt a little alone now, with nothing to do other than sit quietly, back straight, knees pressed together, observing all that was happening around her. Some of the men seemed to know each other – she guessed from previous voyages. These people seemed to only need sign some sort of form and have an entry made in a book they each carried. But they weren’t leaving immediately, and Emma overheard two men wishing ‘they’d hurry up and read out the Articles so’s we can go home for our tea’.

At last Violet emerged from the inner room once more, and nodded to Emma. ‘In you go. Chin up, look confident.’

Emma swallowed her nerves and tried to do as Violet had said. The inner office was a plain room with wooden wall panelling, a battered desk and two chairs. The man behind the desk was of middle age, with an impressive set of grey whiskers.

‘Miss Higgins? Your discharge book, if you please.’ He held out a hand.

‘Yes, sir. I mean, yes, I’m Miss Higgins but please, what is a discharge book? I don’t have one …’

‘Ah, a first timer.’ The man leaned back in his chair and looked appraisingly at Emma. ‘Tell me about your experiences and background, if you would.’

Emma launched into the little speech she’d prepared to introduce herself and talk about her years of hotel work. ‘And I have always wanted to work on a ship,’ she finished, ‘ever since I was very little and sailed over to the Isle of Wight.’

The man threw back his head and laughed at this. ‘Well, being on board the world’s finest liner is a little different from the steam packet over to Cowes. But if you can supply references and pass the medical check I think you will do very nicely, Miss Higgins. Now then, through there to see the doctor, bring me your references tomorrow and then we’ll have you sign the Articles and be issued with your very own Seaman’s Discharge Book. It’s used to log all your voyages, and rate your work on each one,’ he explained.

‘Sir, I have references with me already,’ Emma said, pleased with herself for organising that beforehand, even though it had meant admitting to her employer that she was thinking of leaving them. She took the papers out of her pocket and handed them over.

‘Excellent. Then see the doctor, come back straight after and we’ll sort you out.’ He smiled at her and gestured to another door. She thanked him, went through the door, and found herself in a room with a kindly doctor who carried out what she thought was a rather cursory health check.

A few minutes later she was issued with her discharge book, signed a paper called the ‘Ship’s Articles’ and was told to wait with the other successful applicants. There she found Violet talking to the man who’d recognised her.

‘Well?’ Violet said, smiling. Emma guessed Violet must know she’d been successful, as she had joined all the other people being taken on.

‘I’m in!’ Emma said, and was delighted when Violet gave her a quick, spontaneous hug.

‘I’m so glad. There won’t be many women on board, and so us girls have to stick together. Now, in a little while they will read out the Articles of Agreement – that’s what we’ve all signed – so they know we’ve heard them. Just rules and regulations, really. We’ll be issued with uniforms when we go aboard. All new for a new ship! So pleased you’re on board, Emma. It’s a hard life but an exciting and rewarding one. You won’t regret this.’

At that moment, with a grin threatening to split her face in two, Emma felt Violet was absolutely right. She would never regret her decision to go to sea. This was the start of a new and wonderful life.

Chapter 3

Harriet

Harriet moved over to peer into the trunk. It was packed with clothes – grey uniforms, white aprons and caps, knitted stockings. All moth-eaten and mildewed. A hairbrush was tucked down one side. And two framed photos lay face down on top of the clothes. She reached in and picked up the first one.

‘Look, it’s my gran and grandpa. They look very young here – must be when they’d just become engaged.’

‘They look so happy,’ Sally said, taking the photo from her and inspecting it. ‘I’m guessing you’ll want to keep this, then. What’s the other picture?’

Harriet picked it up and turned it over. The frame was a pretty one in carved wood with a black edging that might be badly tarnished silver. And the picture was a sepia image of three girls, the youngest wearing a smock with her hair tied loosely in a ribbon, the older two wearing plain dark dresses, their hair pinned up. The three had similar faces with long noses and gentle smiles, though there was something about one girl’s expression – defiant, as though she was issuing a challenge to the photographer – that made Harriet think she’d be trouble.

‘Who are they, Mum?’ Sally asked, taking the picture from Harriet to look more closely at it.

‘Well, that’s Gran again,’ Harriet said, pointing at one of the girls. ‘And I assume one of these other girls must be her sister. But I have no idea who the third one is.’

‘They look like they are all sisters.’

‘Gran only ever spoke of one sister. She was very fond of her when they were young.’

‘Only when they were young? Don’t tell me, it’s like me and Davina, is it? Great friends till adolescence then that’s it. And you and your brother who you hardly ever see, too,’ Sally said, shaking her head. ‘Does falling out with your sibling run in this family?’

‘Matthew and I didn’t fall out. We just drifted apart, I suppose. Gran’s sister died young. Gran used to tell me tall tales of how her sister had saved her life somehow, but I never quite believed her.’ Harriet smiled at the memories. ‘She used to love telling me stories.’

‘Ah, that’s sad that her sister died young.’ Sally turned the picture over and began carefully opening up the back of the frame, twisting the little catches that held the back board in place. Behind it, a slip of paper was glued to the back of the photo. ‘The Three Higgins Sisters, 1911,’ Sally read out. ‘So there were three of them. I wonder why your grandma never spoke of the other sister?’

Harriet widened her eyes in surprise. ‘Well I never! I wonder, too, why she never mentioned her. You know, sometimes I wish I could go back in time, just for a day, sit at my gran’s knee again and then I could ask her. And this time I’d write everything down so I wouldn’t forget it. She told me so many stories when I was little but I only have such vague memories of them now. I’d love to ask her about this lost sister. What happened to her? What was her name?’

‘I’d love to know too,’ Sally said. ‘Anyway. What do you want to do with all this stuff? It’s mostly clothes underneath.’

‘I’ll throw out the clothes, I think. Look, they’ve had the moths at them.’ Harriet held up a chemise that was full of holes. ‘I’ll keep the pictures. Maybe I can find out this other girl’s name and details. My friend Sheila knows how to check the old census returns – she’s really into all that genealogy stuff. I’ll get her to show me how. If I check on the census returns from the beginning of the century I might be able to find out.’

Sally laughed. ‘Beginning of last century you mean. Maybe the 1901 or 1911 censuses would help. Can I have the trunk, if you don’t want it? It’d be great for storing some of Jerome’s toys, if I clean it up a little.’

A perfect use for it. ‘Of course you can. Right, we’ll need your Charlie to help get this trunk down, next time he’s here.’

‘Sure, I’ll ask him to come round at the weekend. We’ll bring Jerome who’s been begging to see his Nanna again soon.’

‘I’d love to see him, too. Right, what are we tackling next then? Or have you had enough for one day?’

Sally smiled. ‘I’m all right, Mum. Still got time before I need to pick up Jerome. Let’s have a go at some of the old toys, shall we?’

‘OK. Those should be quick to deal with. Keep any you want for Jerome and the rest can go to charity.’

Sally looked at Harriet, tilting her head to one side. ‘You’ve given up on Davina ever bringing her girls here then?’

Harriet bit her lip and shrugged. ‘I’ll never give up. Your dad always said we must never give up on her. But the girls are probably already too old for some of the stuff I kept.’

Sally was already opening a box and tugging items out. She held up a doll, whose hair had been messily cut. ‘Oh my God. Belinda! I haven’t seen you for years!’

Harriet chuckled. ‘I remember when you gave her that haircut then cried because the hair wouldn’t grow back.’

‘That wasn’t me, Mum. That was Davina. I was bloody furious with her for doing it.’

‘No love, it was you. You came to find me, sobbing like the world was ending, and said you’d cut Belinda’s hair but now you wanted it to be long again. It was definitely you.’

Sally shook her head. ‘We thought you’d be cross, so I took the blame. Davina always thought you’d be more angry with her than with me.’

‘That’s not right – I treated you both equally!’ Harriet was astonished. Had Davina really thought that?

‘I thought so. But she didn’t. So when we were little if she did something stupid like this,’ Sally glanced at the mutilated doll, ‘we’d tell you I did it.’

‘You thought I’d be less angry with you because you were the older one?’

Sally shrugged. ‘That might have had something to do with it. I felt protective of her back then.’ She scoffed. ‘Looking back I don’t know why I bothered. She’s not been much of a sister to me for the last fifteen years. Haven’t seen her in all that time.’

‘Yes you have. Briefly, anyway, at your dad’s funeral. Less than a year ago.’ Davina had turned up out of the blue. Harriet had had no way of contacting her younger daughter to tell her her father had died, but she’d put a notice in the Guardian, John’s favourite paper, on the off-chance Davina might see it. And although Sally had refused to, Harriet knew some of the girls’ schoolfriends had posted the news publicly on Facebook, in case Davina was keeping tabs on them quietly.

‘Doesn’t count. She didn’t say two words to me, that day.’ The hurt in Sally’s voice was evident. ‘She sat at the back of the church, hung back at the graveside, then left as soon as Dad was in the ground. Wouldn’t even come back for a cup of tea.’

Harriet remembered all too well. She’d been glad that the news had reached Davina, and pleased that her younger daughter had made the effort to come to the funeral. But her hopes that the occasion might be the start of a reconciliation had been dashed when she’d gone over to give her daughter a hug afterwards, and Davina had stepped away. ‘I just want a moment alone with Dad, then I’ll go. I’ll ring. Hope you’re OK.’ That was all she’d said, those three short sentences. Harriet had gone over the words endlessly, trying to draw comfort from the fact Davina had said she’d ring, that she’d hoped Harriet was OK, that she’d cared enough to come. In the end she’d had to step back and give Davina space to pay her silent respects to her father with whom she’d always got on better than she had with Harriet, especially as a teen. She’d watched as her daughter stood, head bowed, at the graveside for a minute before walking away to a waiting taxi without so much as a farewell or a backward glance.

‘Yes, I know. It hurt me too. But she came. And she did ring me, after.’

‘Two months later, wasn’t it?’

Harriet nodded. ‘And then again a month after that.’ But the last phone call from Davina was four months ago now. Harriet had no number, no address, no email or anything else for her daughter. She’d tried to find her on social media with no luck.

Sally flung a pile of doll’s clothes and a couple of Barbies into the ‘charity’ box. ‘I hate her for what she’s done to you. I thought her running off like that at 17 with that ridiculous rock band was bad enough. It hurt so much when she didn’t come back for my graduation. Or my wedding! But to refuse to talk to us at Dad’s funeral – that was unforgivable.’

Harriet sighed. ‘I suppose she was grieving too, and didn’t want to deal with any kind of emotional reunion on top of it all. Maybe she was thinking of us, that we had enough to cope with, without adding her arrival …’

‘If she really thought that then she shouldn’t have turned up at all. She never bothered at any other family occasion.’

Harriet had to agree. It was Davina’s failure to come to her sister’s graduation that had been the final straw for Sally. And once Sally had made up her mind about something it was very hard to make her change it. She refused to cut Davina any slack at all now. Davina had asked for Sally’s phone number once, but Sally had told Harriet on no account was she to let her sister have it. ‘She made it clear she wanted nothing more to do with me years ago, so therefore she has no right to have my phone number.’

Harriet had pleaded with Sally. ‘Maybe she wants to make up. Maybe she wants to rebuild some bridges; won’t you give her a chance?’ But Sally had been immovable. Even so, on the rare occasions that Davina phoned Harriet, Harriet would pass on news, and Davina would listen politely, sometimes asking a question or two. It wasn’t much, but it was all Harriet could do to keep a fragile thread of relationship alive between her two daughters. She had no idea though, whether Davina had ever forgiven her or Sally for what they’d done on that awful day, just before Davina’s eighteenth birthday.

‘Well, we can chuck this out, for a start.’ Sally was holding up a battered old teddy bear. It had been Davina’s – her inseparable companion from birth till the age of 12. Oddly, when Davina had left home so abruptly it had been the fact she’d not even taken the bear that had cut Harriet the hardest.

‘Pass it here,’ she said, holding out her hand. The bear was missing an eye, and one leg was badly sewn on with pink knitting wool – Davina’s own attempt to repair him after he’d been in an altercation with a visiting puppy.

‘You’re not keeping it, are you?’ Sally’s tone was incredulous.

‘I remember John buying it for Davina, and bringing it into hospital just after she was born. It holds memories for me. I think I will hang onto him.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.