Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

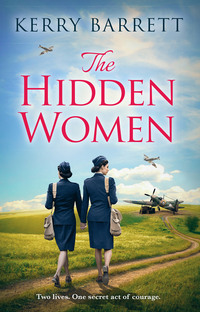

Kitabı oku: «The Hidden Women», sayfa 2

Chapter 3

Lilian

June 1944

‘That’s your brother isn’t it? And is that his wife?’

Rose was peering over my shoulder at the photograph I kept stuck on the inside of my locker.

‘He looks like you, your brother.’

I gave her a quick, half-hearted smile and reached inside my locker for my jacket.

‘And is that their little lad she’s holding?’ Rose went on, undeterred by my lack of responses. ‘What a sweetheart. He looks like you as well. You’ve all got that same dark hair.’

Rose was one of the most infuriating people I’d ever met. Back when we’d been at school together my mum had told me to be nice.

‘She just wants to be your friend,’ Mum would say. ‘She’s not as good with people as you are.’

Back then, I’d been one of the class leaders. Confident and a bit mouthy. Able to make anyone laugh with a quick retort, and to perform piano in front of all sorts of audiences. But that was before.

I’d not seen Rose for a few years and I was finding her much harder to deal with now. For the thousandth time I cursed the luck that had sent my old school friend to join the Air Transport Auxiliary, and at the same airbase as me.

I pulled my jacket out with a swift yank and slammed the locker door shut, almost taking off Rose’s nose as I did it.

‘Got to go,’ I said.

I shrugged on my jacket, heaved my kitbag on to my shoulder, and headed through the double doors at the end of the corridor and out into the airfield. It was a glorious day, sunny and bright with a light wind. Perfect for flying. I paused by the door, raised my face to the sun and let it warm me for a moment.

The airfield was a hubbub of noise and activity. To my left a group of mechanics worked on a plane, shouting instructions to one another above the noise of the propellers. Ahead of me, a larger aircraft cruised slowly towards the runway, about to take off. It was what we called a taxi plane, taking other ATA pilots to factories where they’d pick up the aircraft they had to deliver that day.

My friend Flora was in the cockpit and she raised her arm to wave to me as she passed. I lifted my own hand and saluted her in return. A little way ahead, a truck revved its engine, and all around, people were calling to each other, shifting equipment and getting on with their tasks. I smiled. That was good. It was harder to organise things when it was quiet.

Glancing round, I saw Annie. She was loading some tarpaulins on to the back of a van. Casually I walked over to where she stood.

‘Morning,’ I said.

She nodded at me and hauled another of the folded tarpaulins up on to the van.

‘I’m going to Middlesbrough,’ I said, dropping my kitbag at my feet. I picked up one of the tarpaulins so if anyone looked over they’d see me helping, not chatting. ‘Finally.’

She nodded again.

‘I’ve left the address in your locker with my timings,’ I went on. ‘She’s waiting to hear from you so send the telegram as soon as I take off.’

‘Adoption?’ Annie said.

I nodded, my lips pinched together. ‘Older,’ I said. ‘Three kids already. Husband’s in France.’

Annie winced. ‘Poor cow.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘Her mum’s helping.’

‘How far along is she?’

‘About seven months. She reckons she can’t hide it much longer. I’ve been waiting for one of us to be sent up there.’

Annie heaved the last tarpaulin on to the van.

‘Best get going then,’ she said.

I gave her a quick smile.

‘Thanks, Annie,’ I said.

A shout from across the airfield made me look round. ‘Lil!’

One of the engineers was waving to me from beside a small single-engine Fairchild.

‘Looks like mine,’ I said to Annie.

She gave my arm a brief squeeze. ‘It’s a good thing you’re doing here,’ she said.

‘You’re doing it too.’

Without looking back at her, I picked up my bag and ran over to the plane.

‘Am I flying this one?’ I said. We all took it in turns to fly the taxi planes, but I did it more often than some of the others; I loved it so much.

The engineer – a huge Welsh guy called Gareth who I was very fond of – patted the side of the plane lovingly.

‘You are,’ he said. ‘She’s a bit temperamental on the descent so take it easy.’

I rolled my eyes. ‘Gareth,’ I said. ‘I know what I’m doing.’

I opened the cockpit door and flung my bag inside.

‘Right,’ I said. ‘Take me through all the pre-flight checks.’

I’d been in the ATA for two years now, and I was cleared to fly every kind of plane – even the huge bombers that many people thought a woman couldn’t handle, but I never took anything for granted. I always went through checks with the engineers and did everything by the book. I liked feeling in control and I didn’t want to put my life in anyone else’s hands. Not again.

The taxi flights were quick – normally twenty minutes or so as we headed to the factories to pick up our planes. Today was the same. So it wasn’t long before we’d landed at South Marston, and I was ready to take off in the Spitfire I was delivering to Middlesbrough.

I climbed up into the plane and checked all the instruments, even though I’d flown hundreds of Spitfires and it was as familiar to me as the back of my own hand.

I loved flying. I loved feeling the plane doing what I asked it to do, and the freedom of swooping over the countryside. I’d spent two years hanging round the RAF base near where I lived in the Scottish borders before I joined up. I’d learned everything I could about flying, without actually piloting a plane myself. And then, as soon as I was old enough to sign up I’d applied to the ATA. I’d loved it straight away and I knew I was a good pilot. I’d raced through the ranks and completed my training on each category of plane faster than anyone else.

And yet every time I went on one of my ‘mercy missions’ as Flora called them, I was risking it all.

Putting all my worries aside, I focused on the plane. I watched the ground crew as they directed me out on to the runway, then thought only of the engine beneath me as I took off northwards.

Once I was up, I relaxed a bit, and took in the view. The day was so clear, I could see the towns and villages below. I imagined all the people going about their lives – hearing my engine and looking up to see me as I passed. Because it was a brand new plane, there was no radio, no navigation equipment – nothing. I liked the challenge that brought. It meant my brain was always kept active and I had no time to brood.

Middlesbrough was one of our longest flights and by the time I landed it was afternoon and the heat of the summer day was beginning to fade.

I slid out of the cockpit and headed to a man with a clipboard, who appeared to be in charge.

‘Spitfire,’ I said. ‘Made in South Marston.’

He nodded, without looking at me. ‘Where’s the pilot?’ he asked. ‘I need him to sign.’

‘I’m the pilot,’ I said, through gritted teeth. ‘Do you have a pen?’

Now the man did look up. He rolled his eyes as though I’d said something ridiculous and handed me a pen from his shirt pocket.

I scribbled my signature on the form he held out. ‘Is there a flight going back?’

‘Over there,’ he said, gesturing with his head to where a larger Anson sat on the runway. ‘But there are a few of you going. Be about an hour?’

I breathed out in relief. An hour was more than enough. ‘Fine,’ I said. ‘Can I grab a cuppa?’

He pointed his head in the other direction. I picked up my bag and went the way he’d indicated. But instead of going inside the mess hut, I slipped round the side of the building and out towards the main gate. I hoped the woman would be here – I didn’t want to risk missing my flight back; that would lead to all sorts of trouble.

‘Just going for some cigarettes,’ I told the bored man on the gate. He barely acknowledged me as I sauntered past and out on to the road. It was quiet with no passing traffic. Across the carriageway, a woman stood still, partly hidden by a tree. She was wearing a long coat, even though it was summer, and she was in her late thirties. Her hair was greying and she had a slump to her shoulders that made me sad. She looked at me and when I raised my hand in greeting, she smiled a cautious, nervous smile. Confident she was the person I was meant to meet, I ran across the road to her.

‘April?’ I said.

She nodded, looking as though she was going to cry.

‘I’m Lil.’

‘Lil,’ April said in a strong north-east accent. ‘I need to go. I went early with my others and I’m sure this one’s no different. I can’t be here when the baby arrives. I can’t.’ Her voice shook.

I took her arm. ‘I’ve got a family in Berkshire,’ I said. ‘Lovely woman. She’s wanted a baby since they got married ten years ago but it’s not happened. Her husband’s a teacher – so he’s not off fighting. They’ve got a spare room for you.’

April flinched and I looked at her.

‘He was a teacher,’ she said. ‘The man. The baby’s father.’

I stayed quiet. Sometimes mothers wanted to talk and sometimes they didn’t but whatever they wanted, it was easier for me to stay silent.

‘He was so nice,’ April went on. ‘Charming. Kind to my boys. Helpful to me. You know?’

I nodded.

‘And then one day he wasn’t so nice,’ she said. ‘And I know I should have told him to stay away, that I was married. I should have made it clearer. But I missed Bill, you see. And I know it’s my fault.’

She paused.

‘It’s my fault.’

‘It’s not your fault,’ I said, wondering how many times I’d said that and why it was easy to tell others that and not myself. ‘And it’s not the baby’s fault.’

I unzipped my bag and pulled out an envelope.

‘Your train tickets are in here,’ I said. ‘And the name and address of the family. You need to change at Birmingham and they’ll meet you at Reading station – they know what train you’ll be on.’

Looking a bit stunned, April took the envelope. ‘Why do you do this?’ she asked. ‘What’s in it for you?’

I shrugged. ‘It’s the right thing to do,’ I said.

April looked doubtful but she didn’t argue.

I glanced at my watch.

‘I have to go,’ I said. I took her hand and squeezed it. ‘Good luck.’

Chapter 4

Helena

May 2018

After dinner I cornered Miranda in the kitchen as we washed up.

‘What was all that about?’ I asked her.

‘Should we club together and buy the parents a dishwasher,’ she said, squirting washing-up liquid into the sink.

‘I can’t afford it,’ I said. ‘And they wouldn’t use it anyway.’

Miranda frowned. ‘True.’

I elbowed her in the ribs as I passed her a stack of dirty plates.

‘Miranda, focus. Did you see Mum and Dad look at each other when I mentioned Lil?’

She elbowed me back like we were still ten and twelve, not thirty-four and thirty-six.

‘That was a bit weird, wasn’t it?’ she said.

‘What was weird, darling?’ Mum wandered into the kitchen clutching two empty wine glasses. ‘Is there another bottle?’

I thought Miranda might burst with the effort of not rolling her eyes. ‘In the fridge,’ she said, through gritted teeth. ‘You watched me put it in there.’

Mum blew an air kiss in her direction. ‘Don’t get snappy, Manda,’ she said, mildly. ‘What was weird?’

‘Work stuff,’ I said. ‘Manda was telling me about some really important deal she’s doing. Worth millions. Trillions even.’

Miranda was the youngest ever head of international investment at Ravensberg Bank and also the first woman to do the job. I was fiercely, wonderfully proud of her and in total awe of her skills. Our anti-capitalist parents, however, thought it was terrible. They always appeared faintly ashamed of Manda’s money, which I thought was ironic considering she’d honed her financial management skills by organising the family budget before she hit her teens. And she still invested both of our parents’ erratic income wisely and made sure they never ran short.

In fact, thanks to Dad composing the scores for huge blockbuster films since the Nineties, and Mum’s enthusiastic love of art history earning her spot as an expert on an antiques valuation television show, my parents were both pretty wealthy. Not that they’d ever admit it. If they even knew. They shared a vague ‘it’ll all work out’ approach to money and mostly ignored anything Miranda said about it.

‘Urgh,’ said Mum, predictably. ‘It all sounds so immoral somehow, finance chat.’

I grinned at Miranda over Mum’s shoulder and she scowled at me.

‘Take the bottle into the lounge,’ she said to Mum. ‘We’ll be in when we’re done.’

‘Is Dora asleep?’ I asked. Friday nights were dreadful for my daughter’s carefully crafted routine. She absolutely adored my parents and tended to run round like a mad thing for the first half of the evening, then drop.

‘Curled up on the sofa like an angel,’ Mum said, soppily. The adoration went both ways.

‘And Freddie?’

‘Playing piano with your father,’ Mum said.

Freddie was Miranda’s seven-year-old son who could be adorable and vile in equal measures but who had apparently inherited Dad’s musical talent – much to our father’s delight.

Mum opened the fridge, took out the bottle and retreated. I turned to Miranda, who’d finished the washing up.

‘So, you saw the look, right?’

She nodded.

‘What do you think it meant?’

Miranda shrugged. ‘Probably something completely unrelated, knowing them,’ she said. ‘They were interested though. Dad especially. Do you think it is our Lil?’

‘No,’ I said, though I wasn’t as sure as I sounded.

‘Where did you see her name?’ Miranda asked. She pulled out the wooden bench that lived under the kitchen table and sat down with a sigh. ‘I’m exhausted. Freddie was up half the night.’

I didn’t want to talk about Freddie; I wanted to talk about Lil.

‘On a list of people approved to fly bombers,’ I said.

‘Did women fly planes in the war?’

I nodded. ‘I don’t know a whole lot about it, but it seems so. Not in combat, obviously.’

‘Obviously,’ said Miranda drily. ‘It’s funny that Lil’s never mentioned this because it sounds amazing. Flying bombers?’

‘Not just bombers,’ I said. ‘The records I found are from something called the Air Transport Auxiliary. They flew all the planes. Took them from the factories where they were built to wherever they were needed.’

‘And it was women doing this?’

‘Mostly,’ I said. ‘But men did it too. Jack Jones’s grandad did it because he was too short-sighted to join the regular RAF, which is faintly terrifying.’

Miranda chuckled.

‘But yes, mostly women. They called them the Attagirls.’

‘I like that,’ Miranda said. ‘It’s clever. And only a tiny bit patronising.’

It was my turn to laugh. ‘They were really impressive,’ I said.

‘What’s incredible,’ Miranda said, shaking her head, ‘is that I’ve never even heard of these women.’

‘I’ve not heard much about them either,’ I admitted. ‘And it’s literally my job.’

‘If it was our Lil, I can’t believe she’s never talked about it,’ said Miranda. ‘It strikes me as something you’d want to talk about. It sounds wonderful.’

‘She’s always been vague when I’ve asked her about the war. Never really told me what she did.’

‘She’d have only been about to turn sixteen when the war started,’ Miranda said. I was impressed; I’d been sneakily counting on my fingers trying to add it up. ‘And only twenty-one at the end.’

‘Old enough to be doing something,’ I pointed out. ‘I had an idea she did office work.’

Miranda screwed up her nose. ‘I can’t believe we’ve never been interested enough to ask her for the details,’ she said. ‘That’s terrible of us. You’re a historian, Nell. You should be ashamed of yourself.’

I stuck my tongue out at her. ‘I’ve asked her lots of times,’ I said. ‘She’s always told me how boring it was and how she couldn’t wait for the war to finish so she could travel.’

‘Sounds like she was trying to make it sound dull enough so you wouldn’t keep asking,’ Miranda said.

I blinked at her. ‘Oh God, it actually does sound like that,’ I said. ‘Do you think she saw some awful stuff? Or did some really brave things?’

‘Lil?’ Miranda said with a glint in her eye. ‘Brave? I’d say so, wouldn’t you?’

I thought about our great-aunt, who’d been the only person to step in when things were really tough for us back in the Nineties. Lil, who hated being in one place for long, but who’d stayed in London until she knew Miranda and I were okay and that our family wasn’t about to fall apart. Lil, who regularly phoned Dad throughout our childhood and reminded him about parents’ evenings, and exams, and even birthdays. I smiled.

‘Definitely,’ I said.

I perched on the table next to where Miranda was sitting on the bench, and put my feet up next to her. She frowned at me and I ignored her.

‘The ATA girls flew every kind of aircraft,’ I said. ‘Massive bombers, and tiny fighter planes, and everything in between.’

‘Do you think they got a hard time from people who didn’t think they were capable?’ Miranda asked, well aware of what it was like to be a woman in a man’s world. ‘I have lost count of the times someone’s asked me to take minutes in a meeting, or fetch coffee.’

‘Because you’re the only woman?’ I said, shocked but not entirely surprised. ‘What do you say when that happens? Do you go?’

‘It doesn’t happen now because I’m in charge.’ Miranda allowed herself a small, self-satisfied smile. ‘But when I was starting out, I used to just do it – go and get the drinks, or hand round the biscuits.’

I winced. ‘And when you weren’t just starting out?’

‘Once,’ said Miranda coolly, ‘I asked if I was expected to take the minutes with my vagina.’

‘No, you didn’t.’

‘I did,’ she said, laughing. ‘That was one chief exec who never asked me to do that again.’

I was amazed by her bolshiness and said so. ‘You definitely share that with Lil,’ I pointed out. ‘I expect she had to be bolshie if she was flying planes all over the place, just like you had to be a bit gobby to make it in your job.’

‘She’s definitely bolshie, our Lil. But I suppose we don’t even know for sure the Lilian Miles on this list of yours is her,’ Miranda said. ‘It actually could be a coincidence, like you said.’

We both stayed quiet for a second, then Miranda spoke again.

‘We should ask her,’ she said.

‘Ask her?’

Miranda nodded. ‘Ask her.’

Chapter 5

Lilian

June 1944

It was late when I finally landed back at base. The sunny skies that had made flying such a joy were now chilly and as I slid out of the back of the Anson, I scanned the horizon. It was a clear night, which meant a good view for German bombers, and I wondered if there would be a raid later.

Once I’d signed the plane in and reported to the officer on duty, I picked up my bag and headed off towards the entrance of the airfield. I was tired and I wanted to get back to the digs that I shared with Annie and Flora. We needed to go over all the details of April’s case, and I wanted to check if anything else had come up today.

‘What’s in your bag?’

The voice made me jump. I squinted into the lengthening shadows round the side of the mess hut.

‘Who’s there?’

‘It’s me.’ The shadows changed into the shape of a man and out from the side of the building came Will Bates – one of the RAF mechanics who worked on the base. He was funny and charming and I knew Rose was quite sweet on him.

‘Hello, Will,’ I said, gripping my bag slightly tighter. There was nothing incriminating in it; I’d given everything to April, but his level stare was making me nervous.

‘You’re always carrying a load of stuff,’ he said. ‘I just wondered what you were lugging around the whole time.’

We all carried overnight bags whenever we went on a trip because sometimes we couldn’t get back to HQ. But the way he said it made me feel uncomfortable. I raised my chin.

‘Been watching me, have you?’

To my surprise, Will looked a bit sheepish. ‘I have as it happens,’ he said.

I narrowed my eyes and stared at him. ‘Why?’

He coughed in a sort of nervous way and I relaxed my grip on the straps of my bag, just a bit.

‘Because you’re pretty,’ he muttered. ‘And you look fun. I thought you might like to go dancing one evening, when we’ve both got the same day off.’

I closed my eyes briefly, feeling relief flood my senses.

Will smiled at me. He was a good-looking chap, with dark red hair and deep brown eyes. When he smiled, I got a glimpse of the little boy he’d once been – probably thanks to the sprinkling of freckles across his nose. I couldn’t help but smile back.

‘Dancing?’ I said.

‘Dancing.’

I leaned against the rough wall of the mess hut and took a breath.

‘Will,’ I began. Oh, how to even start explaining the mess my head was in, and the difficult feelings I had about men and women and the relationships between them.

‘I’d like that,’ I said. ‘But maybe we could go as part of a group?’

Will studied me closely. ‘A group,’ he said.

‘At first, at least.’

He grinned again. ‘You’re on,’ he said. ‘See you later.’

He pulled a packet of cigarettes out of his pocket and lit one, the flare from the match shining on the curl of his lip and the twinkle in his eye.

‘Bye, Lil,’ he said, sauntering away across the airfield.

I watched him go. ‘Bye,’ I said.

But as I turned towards the barracks, he stopped.

‘Oh, Lil,’ he said, with that boyish grin again. ‘I know you’re up to something.’

Unease gripped me, but I pretended I hadn’t heard. I shifted my bag up my shoulder and carried on walking away from him. I didn’t look back.

* * *

‘He said what?’ Annie said, when I told her about the conversation.

‘That I was up to something,’ I said. I was lying on my bed in my nightgown, even though it was still early. Missions like tonight’s always exhausted me, and Will’s appearance hadn’t helped.

‘You are up to something,’ Flora pointed out. She was on my bed too, sitting by my feet. She had a sheaf of paper on her lap.

‘That’s why I’m so nervous,’ I said. ‘Between Rose sniffing around and Will Bates lurking in the shadows, I’m worried people are starting to suspect.’

‘I am positive Will Bates knows nothing,’ Annie said. ‘He’s just teasing you. Flirting.’

I scowled at her.

‘I’m positive,’ she repeated. ‘He may be pretty …’

She paused to give Flora and me time to appreciate Will’s handsome face in our imaginations.

‘… but he’s not the sharpest tool in the box.’

I smiled at Annie’s bluntness. She certainly told it how it was and she did not suffer fools gladly. Her sharp brain made her a real asset to our little group, while Flora’s organisational skills kept the whole thing running smoothly. I’d lost count of how many times I thanked my lucky stars that they’d both joined the ATA instead of using their skills in the War Office or behind a desk somewhere.

The first time we’d helped a woman, it was just by chance. Back in 1942 when we’d been doing our training in Luton there had been a girl in our pool called Polly. One evening we’d all been out – it was fun there, and there were a lot of army regiments stationed nearby, lads doing basic training just like us. Their presence always made for a good night. But that one evening, Polly didn’t come home. She eventually arrived, much later, with her dress torn. She hadn’t told us what had happened – she didn’t have to. Quietly, me and Annie gave her a bath and cleaned her up, and tried not to wince at the bruises on her thighs.

A few weeks later, Annie caught Polly being sick in the toilet and realised she was pregnant.

‘What am I going to do?’ Polly had hissed at us in the bathroom that day, her face pale and her forehead beaded with sweat. ‘I can’t have a bloody baby.’

She’d gagged, just with the effort of speaking.

‘I didn’t even know his name.’

‘We need to help her,’ I told Annie.

‘But what can we do?’

I’d shaken my head. ‘I don’t know,’ I’d said. ‘But we need to do something.’

I’d not known Annie long at that time, but I already knew she was someone I’d trust with my life.

‘Someone helped me once,’ I’d admitted. ‘Not like this, not …’

Annie’s eyes had searched my face. I’d squeezed my lips together in case I cried.

‘And now you think we should help Polly?’ she’d said.

I’d nodded.

‘We’ll find a way.’

And that’s where Flora came in. She knew someone in Manchester. Someone who’d helped a friend of her sister. A doctor. At least, that’s what he said he was and we never checked. Flora made the arrangements, Annie and I worked out the logistics and the transport, and Polly went off to Manchester just a fortnight later. She came back even paler, but after a couple of days’ rest – we told our officers that she was having some women’s troubles and they didn’t push it – she was fine again.

We had thought that was it. But it wasn’t. Polly told someone what we’d done for her, and quietly, word got round. Turned out there were women all over the place who needed help of one sort or another and it seemed we were the ones to help them. Gradually we built up a network of people, all over the country. Truth was, the network had existed long before we came along. We were just lucky that we could put people in touch with each other. Doctors who could do what we needed them to do, women desperate to adopt a baby, others willing to shelter a pregnant woman for a few weeks – or nurse someone who’d picked up an infection after their, you know, procedure.

We criss-crossed the country delivering planes, and sharing information or arrangements with women while we did it. In two years, we’d helped eleven women – April was number twelve. We’d seen five babies born and adopted and the rest, well, they’d been sorted. And we’d had one death, a young woman called Bet who lost too much blood after her op, and who’d been too scared to go to hospital in case she got into trouble. We didn’t use that doctor again and we’d made sure we checked out new places now, but we were all haunted by Bet’s death. Never thought about stopping though. Not once. And if losing one of our women wouldn’t stop us helping others, nor would Will Bates and his clumsy flirting.

I sat up in bed and looked across at Annie, who was lying on her own bed next to mine.

‘April’s going to let us know when the baby comes,’ I said. ‘Don’t reckon it’ll be long.’

Annie nodded. ‘Glad we got there in time.’

Flora was opening letters. We had a box at the local post office where people could contact us.

‘Too late for this one, though,’ she said, scanning the paper. ‘She wrote this last month and she says she was already eight months gone then. She’ll have had the baby by now.’

Annie shrugged. ‘Can’t help ’em all.’

But I wished we could.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.