Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

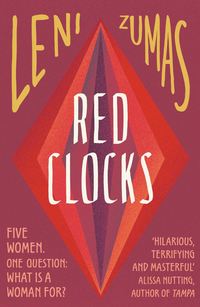

Kitabı oku: «Red Clocks», sayfa 2

You needed a boat to reach the lighthouse, a quarter mile from shore, and if a storm hit, you slept overnight in a reindeer bag on the watch room’s slanted floor.

During storms the polar explorer stood on the lantern gallery, holding its rail as if her life depended on it, because her life did. She loved any circumstance in which survival was not assured. The threat of being swept over the rail woke her from the lethargy sluggery she felt at home chopping rhubarb, cracking puffin eggs, peeling the skin off dead sheep.

THE DAUGHTER

Grew up in a city born of the terror of the vastness of space, where the streets lie tight in a grid. The men who built Salem, Oregon, were white Methodist missionaries who followed white fur-trade trappers to the Pacific Northwest, and the missionaries were less excited than the trappers by the wildness foaming in every direction. They laid their town in a valley that had been fished, harvested, and winter-camped for centuries by the Kalapuya people, who, in the 1850s, were forced onto reservations by the U.S. government. In the stolen valley the whites huddled and crouched, made everything smaller. Downtown Salem is a box of streets Britishly named: Church and Cottage and Market, Summer and Winter and East.

The daughter knew every tidy inch of her city neighborhood. She is still learning the inches in Newville, where humans are less, nature is more.

She stands in the lantern room of the Gunakadeit Lighthouse, north of town, where she has come after school with the person she hopes to officially call her boyfriend. From here you can see massive cliffs soaring up from the ocean, rust veined, green mossed; giant pines gathering like soldiers along their rim; goblin trees jutting slant from the rock face. You can see silver-white lather smashing at the cliffs’ ankles. The harbor and its moored boats and the ocean beyond, a shirred blue prairie stretching to the horizon, cut by bars of green. Far from shore: a black fin.

“Boring up here,” says Ephraim.

Look at the black fin! she wants to say. The goblin trees!

She says, “Yeah,” and touches his jaw, specked with new beard. They kiss for a while. She loves it except for the tongue thrusts.

Does the fin belong to a shark? Could it belong to a whale?

She draws back from Ephraim to look at the sea.

“What?”

“Nothing.”

Gone.

“Wanna bounce?” he says.

They race down the spiral staircase, boot soles ringing on the stone, and climb into the backseat of his car.

“I think I saw a gray whale. Did you—?”

“Nope,” says Ephraim. “But did you know blue whales have the biggest cocks of any animal? Eight to ten feet.”

“The dinosaurs’ were bigger than that.”

“Bullshit.”

“No, my dad’s got this book—” She stops: Ephraim has no father. The daughter’s father, though annoying, loves her more than all the world’s gold. “Anyway,” she says, “here’s one: A skeleton asks another skeleton, ‘Do you want to hear a joke?’ Second skeleton says, ‘Only if it’s humerus.’”

“Why is that funny?”

“Because—‘humerus’? The arm bone?”

“That’s a little-kid joke.”

Her mom’s favorite pun. It’s not her fault he didn’t know what a humerus was.

“No more talking.” He goes to kiss her but she dodges, bites his shoulder through the cotton long sleeve, trying to break the skin but also not to. He gets her underpants down so fast it feels professional. Her jeans are already flung to some corner of the car, maybe on the steering wheel, maybe under the front seat, his jeans too, his hat.

She reaches for his penis and circles her palm around the head, like she’s polishing.

“Not like that—” Ephraim moves her hand to grip the shaft. Up down up down up down. “Like that.”

He spits on his hand and wets his penis, guides it into her vagina. He shoves back and forth. It feels okay but not great, definitely not as great as they say it should feel, and it doesn’t help that the back of her head keeps slamming against the door handle, but the daughter has also read that it takes some time to get good at sex and to like it, especially for the girl. He has an orgasm with the same jittery moan she found weird at first but is getting used to, and she is relieved that her head has stopped being slammed against the door handle, so she smiles; and Ephraim smiles too; and she flinches at the sticky milk dribbling out of her.

The explorer went to the lighthouse whenever allowed, at first, and once she could handle the boat alone, even when forbidden. Her uncle Bjartur felt bad that her father was dead and so let her come, although she bothered him with her questions; he was a lighthouse keeper, God knows, because he preferred his own company, but this little one, this Eivør, youngest of his favorite sister, he could find it in his chewed heart to let her run up the spiral stairs and dig through his trunk of ships’ debris and on drenched tiptoes watch the weather.

THE WIFE

Between town and home is a long twist of road that hugs the cliffside, climbing and dipping and climbing again.

At the sharpest bend, whose guardrail is measly, the wife’s jaw tenses.

What if she took her hands off the wheel and let them go?

The car would jump along the top branches of the shore pines, tearing a fine green wake; flip once before building speed; fly past the rocks and into the water and down forever and—

After the bend, she unclenches.

Almost home.

Second time this week she has pictured it.

Soon as the groceries are in, she’ll give herself a few minutes upstairs. It won’t kill them to watch a screen.

Why did she buy the grass-fed beef? Six dollars more per pound.

Second time this week.

They say grass-fed has the best fats.

Which might be entirely common. Maybe everyone pictures it, maybe not as often as twice a week but—

A little animal is struggling across the road. Dark, about a foot long.

Possum? Porcupine? Trying to cross.

Maybe it’s even healthy to picture it.

Closer: burnt black, scorched to rubber.

Shivering.

Already dead, still trying.

What burned it? Or who?

“You’re making us crash!”—from the backseat.

“We’re not crashing,” says the wife. Her foot is capable and steadfast. They will never crash with her foot on the brake.

Who burned this animal?

Convulsing, trembling, already so dead. Fur singed off. Skin black rubber.

Who burned you?

Closer: it’s a black plastic bag.

But she can’t unsee the shivering thing, burnt and dead and trying.

At the house: unbuckle, untangle, lift, carry, set down.

Unpack, put away.

Peel string cheese.

Distribute string cheese.

Place Bex and John in front of approved cartoon.

Upstairs, the wife closes the sewing-room door. Sits cross-legged on the bed. Fixes her stare on the scuffed white wall.

They are yipping and pipping, her two. They are rolling and polling and slapping and papping, rompling with little fists and heels on the bald carpet.

They are hers, but she can’t get inside them.

They can’t get back inside her.

They are hurling their fists—Bex fistier, but John brave.

Why did they name him John? Not a family name and almost as dull as the wife’s own. Bex had said, “I’m going to call the baby Yarnjee.”

Is John brave, or foolish?—he squirms willingly while his sister punches. The wife doesn’t say No hitting because she doesn’t want them to stop, she wants them to get tired.

She remembers why John: because everyone can spell and say it. John because his father hates correcting butchered English pronunciations of his own name. The errors of clerks. John is sometimes Jean-voyage; and Ro calls him Pliny the Younger.

In the past hour, the kids have

Rolled and polled.

Eaten leftover popcorn stirred into lemon yogurt.

Asked the wife if they could watch more TV.

Been told no.

Slooped and chooped.

Tipped over the standing lamp.

Broken an eyelash.

Asked the wife why her anus is out in space when it should be in her butt.

Slapped and papped.

Asked the wife what’s for dinner.

Been told spaghetti.

Asked the wife what does she think is the best kind of sauce for butt pasta.

The grass-fed beef grows blood in a plastic bag. Does contact with the plastic cancel out its grass-fedness? She shouldn’t waste expensive meat in spaghetti sauce. Marinate it tonight? There’s a jar of store sauce in the—

“Take your finger out of his nose.”

“But he likes it,” says Bex.

And broccoli. Those par-baked dinner rolls are delicious, but she isn’t going to serve bread with pasta.

Sea-salt-almond chocolate bar stowed in the kitchen drawer, under the maps, please still be there, please still be there.

“Do you like having your sister’s finger stuck up your nose?”

John smiles, ducks, and nods.

“When the fuck is dinner?”

“What?”

Bex knows her crime; she eyes the wife with a cunning frown. “I mean when the gosh.”

“You said something else. Do you even know what it means?”

“It’s bad,” says Bex.

“Does Mattie ever say that word?”

“Um …”

Which way will her girl’s lie go: protect or incriminate?

“I think maybe yes,” says Bex dolefully.

Bex loves Mattie, who is the good babysitter, much preferred over Mrs. Costello, the mean. The girl when she lies looks a lot like her father. The hard-sunk eyes the wife once found beguiling are not eyes she would wish upon her daughter. Bex’s will have purplish circles before long.

But who cares what the girl looks like, if she is happy?

The world will care.

“To answer your question, dinner is whenever I want it to be.”

“When will you want it to be?”

“Don’t know,” says the wife. “Maybe we just won’t have dinner tonight.”

Sea-salt-almond. Chocolate. Bar.

Bex frowns again, not cunningly.

The wife kneels on the rug and pulls their bodies against her body, squeezes, nuzzles. “Oh, sprites, don’t worry, of course we’ll have dinner. I was joking.”

“Sometimes you do such bad jokes.”

“It’s true. I’m sorry. I predict that dinner will happen at six fifteen p.m., Pacific standard time. I predict that it will consist of spaghetti with tomato sauce and broccoli. So what species of sprite are you today?”

John says, “Water.”

Bex says, “Wood.”

Today’s date is marked on the kitchen calendar with a small black A. Which stands for “ask.”

Ask him again.

From the bay window, whose frame flakes with old paint possibly brimming with lead—she keeps forgetting to arrange to have the kids tested—the wife watches her husband trudge up the drive on short legs in jeans that are too tight, too young for him. He has a horror of dad pants and insists on dressing as he did at nineteen. His messenger bag bangs against one skinny thigh.

“He’s home,” she calls.

The kids race to greet him. This is a moment she used to love to picture, man home from work and children welcoming him, a perfect moment because it has no past or future—does not care where the man came from or what will happen after he is greeted, cares only for the joyful collision, the Daddy you’re here.

“Fee fi fo fon, je sens le sang of two white middle-class Québécois-American children!” Her sprites scramble all over him. “A’right, a’right, settle down, eh,” but he is contented, with John flung over his shoulder and Bex pulling open the satchel to check for vending-machine snacks. She’s got his salt tooth. Did she get everything from him? What is in her of the wife?

The nose. She escaped Didier’s nose.

“Hi, meuf,” he says, squatting to set John on the floor.

“How was the day?”

“Usual hell. Actually, not usual. Music teacher got laid off.”

Good.

“Hello, hell!” says Bex.

“We don’t say ‘hell,’” says the wife.

I’m glad she’s gone.

“Daddy—”

“I meant ‘heifer,’” says Didier.

“Kids, I want those blocks off the floor. Somebody could trip. Now! But I thought everyone loved the music teacher.”

“Budget crisis.”

“You mean they’re not replacing her?”

He shrugs.

“So there won’t be any music classes at all?”

“I must pee.”

When he emerges from the bathroom, she is leaning on the banister, listening to Bex boss John into doing all the block gathering.

“We should get a cleaner,” says Didier, for the third time this month. “I just counted the number of pubic hairs on the toilet rim.”

And soap heel crusted to the sink.

Black dust on the baseboards.

Soft yellow hair balls in every corner.

Sea-salt-almond chocolate bar in the drawer.

“We can’t afford one,” she says, “unless we stop using Mrs. Costello, and I’m not giving up those eight hours.” She looks into his blue-gray eyes, level with hers. She has often wished that Didier were taller. Is her wishing the product of socialization or an evolutionary adaptation from the days when being able to reach more food on a tree was a life‑or‑death advantage?

“Well,” he says, “somebody needs to start doing some cleaning. It’s like a bus station in there.”

She won’t be asking him tonight.

She will write the A again, on a different day.

“There were twelve, by the way,” he says. “I know you have stuff to do, I’m not saying you don’t, but could you maybe wash the toilet once in a while? Twelve hairs.”

Red sky at morning, sailor take warning.

THE BIOGRAPHER

Can’t see the ocean from her apartment, but she can hear it. Most days between five and six thirty a.m. she sits in the kitchen listening to the waves and working on her study of Eivør Mínervudottír, a nineteenth-century polar hydrologist whose trailblazing research on pack ice was published under a male acquaintance’s name. There is no book on Mínervudottír, only passing mentions in other books. The biographer has a mass of notes by now, an outline, some paragraphs. A skein draft—more holes than words. On the kitchen wall she’s taped a photo of the shelf in the Salem bookstore where her book will live. The photo reminds her that she is going to finish it.

She opens Mínervudottír’s journal, translated from the Danish. I admit to fearing the attack of a sea bear; and my fingers hurt all the time. A woman long dead coming to life. But today, staring at the journal, the biographer can’t think. Her brain is soapy and throbbing from the new ovary medicine.

She sits in her car, radio on, throat shivering with hints of vomit, until she’s late enough for school not to care that her eye–foot–brake reaction time is slowed by the Ovutran. The roads have guardrails. Her forehead pulses hard. She sees a black lace throw itself across the windshield, and blinks it away.

Two years ago the United States Congress ratified the Personhood Amendment, which gives the constitutional right to life, liberty, and property to a fertilized egg at the moment of conception. Abortion is now illegal in all fifty states. Abortion providers can be charged with second-degree murder, abortion seekers with conspiracy to commit murder. In vitro fertilization, too, is federally banned, because the amendment outlaws the transfer of embryos from laboratory to uterus. (The embryos can’t give their consent to be moved.)

She was just quietly teaching history when it happened. Woke up one morning to a president-elect she hadn’t voted for. This man thought women who miscarried should pay for funerals for the fetal tissue and thought a lab technician who accidentally dropped an embryo during in vitro transfer was guilty of manslaughter. She had heard there was glee on the lawns of her father’s Orlando retirement village. Marching in the streets of Portland. In Newville: brackish calm.

Short of sex with some man she wouldn’t otherwise want to have sex with, Ovutran and lube-glopped vaginal wands and Dr. Kalbfleisch’s golden fingers is the only biological route left. Intrauterine insemination. At her age, not much better than a turkey baster.

She was placed on the adoption wait-list three years ago. In her parent profile she earnestly and meticulously described her job, her apartment, her favorite books, her parents, her brother (drug addiction omitted), and the fierce beauty of Newville. She uploaded a photograph that made her look friendly but responsible, fun loving but stable, easygoing but upper middle class. The coral-pink cardigan she bought to wear in this photo she later threw into the clothing donation bin outside the church.

She was warned, yes, at the outset: birth mothers tend to choose married straight couples, especially if the couple is white. But not all birth mothers choose this way. Anything could happen, she was told. The fact that she was willing to take an older child or a child who needed special care meant the odds were in her favor.

She assumed it would take a while but that it would, eventually, happen.

She thought a foster placement, at least, would come through; and if things went well, that could lead to adoption.

Then the new president moved into the White House.

The Personhood Amendment happened.

One of the ripples in its wake: Public Law 116‑72.

On January fifteenth—in less than three months—this law, also known as Every Child Needs Two, takes effect. Its mission: to restore dignity, strength, and prosperity to American families. Unmarried persons will be legally prohibited from adopting children. In addition to valid marriage licenses, all adoptions will require approval through a federally regulated agency, rendering private transactions criminal.

Woozy with Ovutran, inching up the steps of Central Coast Regional, the biographer recalls her high school career on the varsity track team. “Keep your legs, Stephens!” the coach would yell when her muscles were about to give out.

She informs the tenth-graders they must scrub their essay drafts clean of the phrase History tells us. “A stale rhetorical tic. Means nothing.”

“But it does,” says Mattie. “History is telling us not to repeat its mistakes.”

“We might reach that conclusion from studying the past, but history is a concept; it isn’t talking to us.”

Mattie’s cheeks—cold white, blue veined—go red. Not used to correction, she’s easily shamed.

Ash raises her hand. “What happened to your arm, miss?”

“What? Oh.” The biographer’s sleeve is pushed way up above the elbow. She yanks it down. “I gave blood.”

“It looks like you gave, like, gallons.” Ash rubs her piglet nose. “You should sue the blood bank for defamation.”

“Disfigurement,” says Mattie.

“You got straight disfigured, miss.”

By noon the cloudy throb behind her eyebrows has dialed itself back. In the teachers’ lounge she eats maize puffs and watches the French teacher fork pink thumbs out of a Good Ship Chinese takeout box.

“Certain kinds of shrimp produce light,” she tells him. “They’re like torches bobbing in the water.”

How can you raise a child alone when all you’re having for lunch is vending-machine maize puffs?

He grunts and chews. “Not these shrimp.”

Didier has no particular interest in French but can speak it, the tongue of his Montreal childhood, in his sleep. Like being a teacher of walking or sitting. For this predicament he blames his wife. During his first conversation with the biographer, years ago, over crackers and tube cheese in the lounge, he explained: “She says to me, ‘Aside from cooking you have no skills, but at least you can do this, can’t you?’—so ici. Je. Suis.” The biographer then imagined Susan Korsmo as a huge white crow, shading Didier’s life with her great wing.

“Shrimp are sky-high in cholesterol,” says Penny, the head English teacher, deseeding grapes at the table.

“This room is where my joy dies,” says Didier.

“Boo hoo. Ro, you need nourishment. Here’s a banana.”

“That’s Mr. Fivey’s,” says the biographer.

“How can anyone be sure?”

“He wrote his name on it.”

“Fivey will survive the loss of one fruit,” says Penny.

“Ooosh.” The biographer holds her temples.

“You okay?”

Thudding back down into the chair: “I just got up too fast.”

The PA system sizzles to life, coughs twice. “Attention students and teachers. Attention. This is an emergency announcement.”

“Please be a fire drill,” says Didier.

“Let us all keep Principal Fivey in our thoughts today. His wife has been admitted to the hospital in critical condition. Principal Fivey will be away from campus until further notice.”

“Should she be telling everyone this?” says the biographer.

“I repeat,” says the office manager, “Mrs. Fivey is in critical condition at Umpqua General.”

“Room number?” yells Didier at the wall-mounted speaker.

The principal’s wife always comes to Christmas assembly in skintight cocktail dresses. And every Christmas Didier says: “Mrs. Fivey’s gittin sixy.”

The biographer drives home to lie on the floor in her underwear.

Her father is calling again. It has been days—weeks?—since she answered.

“How’s Florida?”

“I am curious to know your plans for Christmas.”

“Months away, Dad.”

“But you’ll want to book the flight soon. Fares are going to explode. When does school let out?”

“I don’t know, the twenty-third?”

“That close to Christmas? Jesus.”

“I’ll let you know, okay?”

“Any plans for the weekend?”

“Susan and Didier invited me to dinner. You?”

“Might drop by the community center to watch the human rutabagas gum their feed. Unless my back flares up.”

“What did the acupuncturist say?”

“That was a mistake I won’t make twice.”

“It works for a lot of people, Dad.”

“It’s goddamn voodoo. Will you be bringing a date to your friends’ dinner?”

“Nope,” says the biographer, steeling herself for his next sentence, her face stiff with sadness that he can’t help himself.

“About time you found someone, don’t you think?”

“I’m fine, Dad.”

“Well, I worry, kiddo. Don’t like the idea of you being all alone.”

She could trot out the usual list (“I’ve got friends, neighbors, colleagues, people from meditation group”), but her okayness with being by herself—ordinary, unheroic okayness—does not need to justify itself to her father. The feeling is hers. She can simply feel okay and not explain it, or apologize for it, or concoct arguments against the argument that she doesn’t truly feel content and is deluding herself in self-protection.

“Well, Dad,” she says, “you’re alone too.”

Any reference to her mother’s death can be relied on to shut him up.

There was Usman for six months in college. Victor for a year in Minneapolis. Liaisons now and again. She is not a long-term person. She likes her own company. Nevertheless, before her first insemination, the biographer forced herself to consult online dating sites. She browsed and bared her teeth. She browsed and felt chest-flatteningly depressed. One night she really did try. Picked the least Christian site and started typing.

What are your three best qualities?

1 Independence

2 Punctuality

3

Best book you recently read?

Proceedings of the “Proteus” Court of Inquiry on the Greely Relief Expedition of 1883

What fascinates you?

1 How cold stops water

2 Patterns ice makes on the fur of a dead sled dog

3 The fact that Eivør Mínervudottír lost two of her fingers to frostbite

But the biographer didn’t feel like telling anyone that. Delete, delete, delete. She could say, at least, she had tried. The next day she called for an appointment at a reproductive-medicine clinic in Salem.

Her therapist thought she was moving fast. “You only recently decided to do this,” he said, “and already you’ve chosen a donor?”

Oh, therapist, if only you knew how quickly a donor can be chosen! You turn on your computer. You click boxes for race, eye color, education, height. A list appears. You read some profiles. You hit PURCHASE.

A woman on the Choosing Single Motherhood discussion board wrote, I spent more time dead-heading my roses than picking a donor.

But, as the biographer explained to her therapist, she did not choose quickly. She pored. She strained. She sat for hours at her kitchen table, staring at profiles. These men had written essays. Named personal strengths. Recalled moments of childhood jubilance and described favorite traits of grandparents. (For one hundred dollars per ejaculation, they were happy to discuss their grandparents.)

She took notes on dozens and dozens—

Pros:

1 Calls himself “avid reader”

2 “Great cheekbones” (staff)

3 Enjoys “mental challenges and riddles”

4 To future child: “I look forward to hearing from you in eighteen years”

Cons:

1 Handwriting very bad

2 Commercial real-estate appraiser

3 Of own personality: “I’m not too complicated”

—then narrowed it to two. Donor 5546 was a fitness trainer described by sperm-bank staff as “handsome and captivating.” Donor 3811 was a biology major with well-written essay answers; the affectionate way he described his aunts made the biographer like him; but what if he wasn’t as handsome as the first? Both of their health histories were perfect, or so they claimed. Was the biographer so shallow as to be swayed by handsomeness? But who wants an ugly donor? But 3811 was not necessarily ugly. But was ugly even a problem? What she wanted was good health and a good brain. Donor 5546 claimed to be bursting with health, but she wasn’t sure about his brain.

So she bought vials of both. She wouldn’t stumble upon 9072, the just-right third, for another couple of months.

“Do you feel undeserving of a romantic partner?” asked the therapist.

“No,” said the biographer.

“Are you pessimistic about finding a partner?”

“I don’t necessarily want a partner.”

“Might that attitude be a form of self-protection?”

“You mean am I deluding myself?”

“That’s another way to put it.”

“If I say yes, then I’m not deluded. And if I say no, it’s further evidence of delusion.”

“We need to end there,” said the therapist.