Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

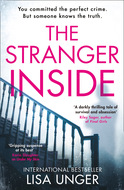

Kitabı oku: «The Stranger Inside»

Even good people are drawn to do evil things…

Twelve-year-old Rain Winter narrowly escaped an abduction while walking to a friend’s house. Her two best friends, Tess and Hank, were not as lucky. Tess never came home, and Hank was held in captivity before managing to escape. Their abductor was sent to prison but years later was released. Then someone delivered real justice—and killed him in cold blood.

Now Rain is living the perfect suburban life, her dark childhood buried deep. She spends her days as a stay-at-home mom, having put aside her career as a hard-hitting journalist to care for her infant daughter. But when another brutal murderer who escaped justice is found dead, Rain is unexpectedly drawn into the case. Eerie similarities to the murder of her friends’ abductor force Rain to revisit memories she’s worked hard to leave behind. Is there a vigilante at work? Who is the next target? Why can’t Rain just let it go?

Introducing one of the most compelling and original killers in crime fiction today, Lisa Unger takes readers deep inside the minds of both perpetrator and victim, blurring the lines between right and wrong, crime and justice, and showing that sometimes people deserve what comes to them.

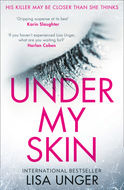

LISA UNGER is the New York Times and internationally bestselling author of seventeen novels. Under My Skin, is an Edgar nominee and finalist for the Hammett Prize. Her story, The Sleep Tight Motel, is a #1 bestselling short and Edgar nominee. Lisa lives on the west coast of Florida with her family.

Also by Lisa Unger:

Under My Skin

The Red Hunter

Ink and Bone

The Whispering Hollows (Novella)

Crazy Love You

In The Blood

Heartbroken

Darkness, My Old Friend

Fragile

Die For You

Black Out

Sliver of Truth

Beautiful Lies

Smoke

Twice

The Darkness Gathers

Angel Fire

The Stranger Inside

Lisa Unger

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Lisa Unger 2019

Lisa Unger asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9781474066761

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Praise for Lisa Unger:

‘Suspenseful, sensitive, sexy, subtle. The best nail-biter I have read for ages. Highly recommended’

Lee Child

‘Lisa Unger’s deliciously intense and addictive thriller got under my skin. I picked it up, was drawn into this dark, tangled tale, and couldn’t pull away until it was done. Gripping suspense at its best’

Karin Slaughter

‘Deeply plotted and complex and carries an undeniable momentum. Lisa Unger’s enthralling cast of characters pulled me right in and locked me down tight. This is one book that will have you racing to the last page, only to have you wishing the ride wasn’t over’

Michael Connelly

‘Riveting psychological suspense of the first order. If you haven’t yet experienced Lisa Unger, what are you waiting for?’

Harlan Coben

‘A perfectly dark and unsettling, spellbinding thriller. Told with both eloquence and urgency, Unger knows just how to hook her readers and reel them in. This book is not to be missed’

Mary Kubica

‘This is a haunting, compulsive tale that will have you under its spell long after you’ve closed the book’

Tess Gerritsen

‘A twisting labyrinth of a book where nothing is as it seems, dreams bleed into reality, and the past is the future. Lisa Unger is one of my favourite writers. And in this tilt-a-whirl of a psychological thriller, she’s at the top of her game’

Lisa Gardner

In loving memory of my wonderful grandmother Millie Miscione

and my magnificent, dear agent and friend Elaine Markson

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Praise

Dedication

Quote

LAST NIGHT

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

FORTY-TWO

FORTY-THREE

FORTY-FOUR

SIX MONTHS LATER

FORTY-FIVE

FORTY-SIX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Extract

About the Publisher

For what is evil but good tortured by its own hunger and thirst?

Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet

LAST NIGHT

I wait because I have nothing but time.

From the quiet, dim interior of my car, I watch the quiet neighborhood, settle into the upholstery. Autumn. Leaves lofting on cool air. Tacky, ghoulish Halloween decorations adorning stoops and lawns, hanging from trees—skeletons, and jack-o’-lanterns, witches on brooms. It’s a school night, so no kids playing flashlight tag, no pickup soccer match in the street. Maybe kids don’t even do that anymore. That’s what I understand, anyway. That they’re all iPad-addicted couch potatoes now. It’s the new frontier of parenting. But you’ll know better about this than I’m likely to.

Younger families live on this block. SUVs are hastily parked. Basketball hoops tilt in driveways; bikes twist on the lawn. Recycling cans wait patiently at the curb on Wednesday, garbage on Friday. Tonight, there’s a game on. I see it playing on big-screen televisions in three different open-plan living rooms.

But the house I’m watching is dark. A beautiful silver Benz that’s about to be repossessed sits in the driveway. It’s one of those cars—the kind that people dream about, an aspirational car, the kind you get when… But it certainly hasn’t brought its owner any happiness. The guy I’m watching—he’s depressed. I can see it in his slouch as he comes and goes, in the haunted circles that have settled around his eyes.

I can’t muster any compassion for him. And I know that you aren’t shedding any tears. In fact, I’m willing to bet that you’ve spent at least as much time thinking about him as I have—even though, of course, you have other things on your mind now.

An older man walks his dog, a white puff of a thing on a slender leash. Not a dog at all really, more like an extra-large guinea pig. I sink a little deeper in my seat, then stay stone-still. I haven’t seen this man on this street before, and I’ve been here most nights for a while. He’s out of his routine, I guess, maybe decided to take a new route tonight. I’m not too worried, though. My car—a beige Toyota Corolla—is utterly forgettable, practically invisible in its commonness; the windows tinted (but not too dark). If he doesn’t see me, a lone person slouched in the driver’s seat and clearly up to no good, he won’t even notice it.

I’m in luck. He’s squinting at the screen on his smartphone. He’s older, not fluent with it. So it takes all of his concentration. That device is the best thing that ever happened to people who want to be invisible. He walks right by, oblivious to the car, to me, to his surroundings. Even his dog is distracted, incurious, nose to the pavement. Sniff, sniff, sniff. Finally, they’re gone and I’m alone again.

Time passes. I breathe into the night.

One by one, windows go dark except for the odd light here and there. There’s an insomniac in 704, a nurse who comes home after 3 a.m. on Wednesdays and Fridays to 708.

Just after 2 a.m., I slip from the car, close the door silently and shoulder my pack. I am a shadow shifting through the shadows of the trees, drifting, silent, up the edge of the house. I easily pick the lock on the side entrance—you can learn how to do anything on YouTube these days—and enter the house through the unlocked interior door. From the garage into the laundry room. From the laundry room into the kitchen—a typical suburban layout. I stand inside for a moment, listening.

I can still hear it, you know, the sound of her father’s voice.

I am willing to bet that you hear it, too. Maybe in those quiet moments, when you lie in bed at night, the wail of total despair comes back like a haunting. I imagine that your mind drifts back to that courtroom. Your face pulled tight with that helpless mingle of anger and sorrow, nostrils flaring just slightly. I was right there with you even though you didn’t know it. Or maybe you did. Sometimes I wonder if you know how close I am. If you sense me.

When the verdict was delivered, there was a moment, remember? A tiny sliver of time where the information moved through synapses and neurons, a heartbeat. In that breath, I watched her mother drain of what little energy and color remained in her too-thin body. I watched her father buckle over, her brother dip his head into his hands. The unforgiving light of the courtroom grew brighter somehow, an ugly white sizzle. And then the room exploded in a wave of sound that contained all the notes of despair, disbelief, rage. I’d been there before, in the presence of injustice, as have you. You know how it wafts like smoke from the black spaces beneath tables and chairs. It rises up, tall and menacing. I was always here, it seems to say as it looms over you, towering, victorious. It brings you to your knees. In the presence of nothing else do you feel smaller or more powerless.

When we’re young, we’re naive enough to believe. We’re raised on the comic-book ideal of good vanquishing evil. We believe that white magic is stronger than black. That criminals are punished, and justice is always served. Even when it seems that evil might triumph—no. In the final moment, a cosmic force does the reckoning for good, one way or another. We want to believe that.

But it’s not so. Not always. Sometimes justice needs a little push.

I make a quick loop through the house to assure myself that everything is as it was the last time I was here. The decor is Target, IKEA chic, white and dove gray, with bold accent patterns. There are lots of those picture collages with words like LOVE and DREAM and FAMILY: her parents—smiling and benevolent; her wedding photos—gauzy, a fairy-tale dream; a gaggle of gap-toothed nieces and nephews; girls’ night out, toasting with pink drinks in martini glasses. Throw pillows and soft blankets, knickknacks, decorative pieces of driftwood are artfully arranged. She was house-proud, the woman who lived here once. She liked things pretty and comfortable. Now, surfaces are covered with dust. Her home, it smells like garbage.

As I finish my tour, I feel a twist of sadness for her. Here’s someone who did everything right. She followed all the rules, went to college, worked in public relations, got married, got pregnant. Pretty, and, by all accounts, sweet and kind. And look. Her cute house, her little dreams, her innocent life, empty, rotting. She deserved better.

Nothing I can do about that. But this is the next best thing.

I know what you’re thinking. What anyone might think. Who am I to say that a man found innocent by a jury of his peers is guilty as sin? And even if he is, who am I to deliver justice?

It’s true. I am no one. But this is how I knew.

When Laney Markham went missing, I immediately suspected that it was her oh-so-handsome husband. Because let’s get real: the incident of stranger crime is a statistical anomaly. (We both have a thing or two to add to that conversation, don’t we? But I’m sure you’d agree that statistically it’s true.) The idea of the other, the stranger, the destroyer who breaks into your home and kills your family, or takes your child? It does happen. But not as often as a man kills his wife. Or a father rapes his daughter. Or an uncle molests his niece. Those things don’t always make the news. Why? Because it’s not news; that’s the everyday horror show of normal life.

So there’s that. The it’s-always-the-husband thing. But what sealed it for me was those national morning show appearances. He did the circuit, ostensibly to plead for the lovely Laney’s safe return. Tall, with movie-star good looks, he was a natural. And those morning show hosts, they lapped it up. Laney? She was a beauty, too. One of those luscious pregnant girls—even prettier with her little baby belly, glowing skin and silky, hormone-rich hair. If the Markhams had been less good-looking, this would have been less of a story. You know it’s true.

Anyway, he gets on camera and starts to weep, and I mean blubber. Steve Markham stares right at the camera, tears streaming down his face and he begs for whoever took his wife and unborn child to just bring them home. Quite a performance.

Except.

Men don’t cry like that. Men, when they are overcome by emotion to the degree that they lose control and start to weep, they cover their faces. Crying is a disobeying of every cultural message a man ever receives. To weep like a woman? It fills him with shame. So he covers his face. That’s how I knew he killed his wife. Steve Markham was a sociopath. Those tears were as fake as they come.

You remember. I know you were thinking the same thing.

You might say that’s not enough. I know you; you follow the rules—or, anyway, you have a kind of code. But we all know there was enough physical evidence to send the bastard to the electric chair. It was those lawyers with all their tricks—cast doubt on this, get that thrown out, confuse and mislead the slack-jawed jury with complicated cell phone evidence. This satellite says he was there at this time, couldn’t have done it.

Still, I generally wait a year. Just to be sure. I watch and wait, do my research. At least a year, sometimes much, much longer, as you know. I choose very carefully. I think about it long and hard. Because it would suck to be wrong. I wouldn’t, couldn’t, justify that. It’s a line I can’t step over. Really. Because then—what am I?

Anyway, my old friend, I’m gratified to report that the year since he was acquitted of his wife’s murder has been very bad for Steve Markham. He lost his job. All his friends. His lover-slash-alibi Tami—you remember her, right? The whole case hung on that mousy blonde from Hoboken. Well, she broke up with him. I’m sure you know all this. If I know you, you’re keeping tabs, too.

You probably didn’t know that for a while he hung around Tami’s place, stalking. I thought we were going to have a problem, that I’d have to act before I was ready. But Steve is nothing else if not a smart guy. Probably figured it wouldn’t look great if his girlfriend turned up dead less than a year after his wife’s body was found in a shallow grave, just miles from her own home, she and her unborn child killed by multiple stab wounds with a six-inch serrated blade (from her own kitchen). He finally stopped following Tami, the one that got away.

He’s about to lose the house. Last month, the lights went out. The pool where they think he killed his wife has turned green, water thick now with algae. Sure, he had his book deal. He did the talk show circuit, this time playing the innocent man, wrongly accused, on a tireless hunt for his wife’s killer. He’d been unfaithful, he admitted, grim and remorseful. He was sorry. So sorry. More crocodile tears.

He burned through the advance money fast. It wasn’t that much. Between agent commission, taxes, it was no windfall. He might have made it last. But people don’t get it. Money, if you don’t protect it, is flammable. It goes up in flames and floats away like ash. The IRS is after him now. The system. Maybe it does have its ways of getting you, even if you slip through its cracks at first.

I make no attempt to be quiet as I unpack my bag. I drape a plastic tarp over the couch, lay another one in front of the door where he will enter the room when he hears me. I lay things out. The duct tape. The hunting knife. There’s a gun I carry in a shoulder holster, the sleek, light Beretta PX4 Compact Carry with a handy AmeriGlo night sight and Talon grip. It’s only meant to inspire cooperation. To have to use it will represent a failure of planning on my part. But there are always variables for which you can’t account.

By the time he rouses from sleep and moves cautiously into the front room, I am sitting in one of the cheap wingback chairs by the window. He is not armed. I know there is no weapon in this house. There was a baseball bat under the bed. Maybe he thought that someday Laney’s brother or her father would come for him. But the baseball bat is gone now. In the trunk of my very forgettable car, in fact.

“Hello, Steve,” I say quietly and watch him jump back. “Have a seat.”

“Who are you?”

I work the Cerakote slide that puts a bullet into the chamber and watch him freeze. It’s a sound a man recognizes even if he’s never had a gun pulled on him before.

“On the couch.”

The plastic tarp crinkles beneath his weight and he starts to cry again. This time? It’s real.

“Please.” His voice is small with fear and regret.

But do I also hear relief?

We all believe that story, that cheaters never win, and justice will be done. Even the bad guys believe it.

Isn’t that right, my old friend?

ONE

It was just a peep, the tiniest little chirp. But Rain’s eyes flew open and she lay there in the dim morning, listening. She could tell by the light outside the window, by the bubbling of nausea in her stomach that it was way too early. Hours before the alarm would go off.

Now a groan, just a light one.

Go back to sleep, she pleaded silently. She pushed her head deeper into the pillows, tugged at the covers. Please, baby.

Now a hiccup, almost a cry.

“Leave her.” Greg, groggy, draped a heavy arm over her middle, pulled her in. “She’ll go back.”

No. She wouldn’t go back. Rain could already tell. Outside her window, the manic chirping of birds. They’d nested in the oak on their lawn, two starlings that chattered all day, starting at dawn. It was cute, a lovely detail of their domestic life. Until it wasn’t.

Now two quick little sounds from the baby monitor on the bedside table. “Eh—Eh.”

She pushed herself up, head full of cotton, stomach churning. She’d been up with the baby just two hours earlier, feeding. Growth spurt.

Greg stirred. “I’ll get her.”

“No.” She put a hand on his shoulder. “Get some more sleep before work.”

Greg sighed, pulled those blissfully soft covers tight around him.

Over the monitor, she heard the baby sigh, too. Then the soft, even sound of Lily’s breath like ocean waves. Rain reached for the monitor and turned on the screen. A perfect cherub floated on a cloud next to a white stuffed bear. A little burrito in her loose fleece swaddle. A wild head of red hair. But no, it wasn’t red—it was white and gold, auburn lowlights and orange highlights. It was fairy princess hair. And her eyes weren’t blue, they were facets of sapphire and sky, sea green.

Her baby was an angel, wasn’t she? Beautiful and sweet beyond expression. Get ready for the biggest love of your life, Andrew, her executive producer, had gushed when she’d announced her pregnancy. He’d teared up a little, gazing at the picture of his twin boys, then ten. And he was right, of course. That love, it changed her—just like everyone said it would. In myriad ways.

But it was also obvious to Rain that her child was trying to kill her. Slowly. With an adorable, gurgling, two-tooth smile.

Death by sleep deprivation. No mercy.

She sank back into bed, closed her eyes. But her brain—as manic and chirpy as her starling neighbors—would not stop chattering.

Finally, she put on her robe and moved quietly down the stairs. Might as well use the time and mill some organic baby food and store it in those perfect little blue-lidded glass jars. Apples. Sweet potatoes. Broccoli. Five a.m., and she had pots boiling on the stove.

She watched them bubble as she drank her coffee. Caffeine. Thank god. She would not have survived the last thirteen months without it. She’d given it up when she was pregnant, but as soon as Lilian Rae made her entrance, Rain was back on the sauce.

She let the aroma wake her, let the magic elixir work its way through her body. The body that was just starting to feel like hers again, now that she was trying to wean the baby—at the not-so-subtle behest of her husband. Greg had walked in while she was nursing Lily to sleep earlier that week. (Yeah, yeah. She knew you weren’t supposed to nurse your baby to sleep. But come on. What other benefit was there in being a human Binky?)

He’d tenderly touched Lily’s silky hair, then gazed at Rain with an odd smile.

“How much longer?” he’d whispered. It was date night. He’d brought home dinner, a bottle of wine.

“Five minutes?”

“No,” he said. “I mean how much longer are you going to nurse her?”

She’d tried not to let her body tense with annoyance, measured her breathing. Mommy gets upset, baby gets upset. That simple.

“I don’t know,” she’d said tightly.

It was one of those loaded moments, air simmering with all the things each of them wanted to say but didn’t. Instead, he’d pressed his mouth into a line—he claimed that expression meant frustration, she read it as disapproval—gave a quick nod, left the room. After some time seething, she’d unlatched the baby, placed her gently in the crib.

How much longer? she’d thought. What kind of question is that?

“I want you back,” he’d said at the table, gentle. He touched her hand. He wasn’t a jerk, was he? One of those clueless men who thought her body existed for his pleasure only. “We said six months.”

“I want me back, too,” she admitted.

She wanted to nurse Lily, loved the closeness of it, those soothing quiet moments with her baby. She wanted her body back, wanted to feel sexy again. It seemed everything about motherhood was this complicated twist of emotion, a delicate balance of holding on and letting go.

And, seriously, those nursing bras? Some of them were cute, but for the most part they looked like pieces of equipment rather than lingerie. She hadn’t felt sexy in ages. How could you be sexy, hot, erotic when you didn’t even own yourself?

“So,” he’d said at dinner that night. “Can we get on a plan?”

Thanks to a Google search—how to wean your baby!—she was on a plan. The morning and midday feedings were solid food now. Which meant she could have a glass of wine at night and not have to “pump and dump” (another sexy bit of breastfeeding terminology). The pediatrician said so. Anyway, she’d vowed never to put that pump back on her breast again. God, how much more like a cow could a thing make you feel?

She could already feel that she was producing less milk. Her breasts were smaller, more familiar. She’d bought some new lingerie, lacy, pretty, no cup clasps in sight. Sexy? She wasn’t feeling it yet. But she was getting there.

She drained the vegetables, milled them into mush, then filled the little jars.

Very sexy.

She liked the way they looked with their cheerful blue tops lined up in the fridge, which was stocked and tidy. Everything in order, everything sorted. There was a satisfaction in it. She ran the house with a frugal, high-end, minimalist zeal. She did the grocery shopping, cooking and day-to-day cleaning. The cleaning lady came once every other week to do the big stuff. She did a load of laundry every day. The dry cleaning, mainly Greg’s work clothes, got picked up on Tuesdays and Thursdays. She ran the house the way she used to do her job—with accuracy and efficiency.

She was only half listening to the news broadcasting from her phone as she wiped down the quartz countertop, though it was already clean. The news was bad, as usual. She tried not to get hooked in as she managed the fresh tulips that dipped from their glass vase, pulling a wilting one, adding more water. On the distressed gray cabinet, she spied a sticky handprint. She wiped it clean. The sun was streaming through the big windows now. She put some of Lily’s toys in the wicker basket, rearranged the fluffy white throw on the cozy sectional where she and Greg spent most of their time now that they were parents—who knew you could watch so much television.

“—Markham, tried and acquitted for the violent murder of his pregnant wife, Laney Markham, was found dead in his home early this morning.”

The words stopped her cold, a board book clutched in her hand. She moved over to her phone, turned up the volume, something other than caffeine pulsing through her system.

The voice was familiar, and not just because Rain listened to this National News Radio broadcast every day, but because the woman speaking was her closest friend and former colleague. And the news show was the one Rain used to write, edit and produce.

“Markham was found not guilty last year in the stabbing death of his wife. His defense leaned heavily on cell phone records that confirmed his alibi that at the time of his wife’s murder, he was out of state with a woman who turned out to be his lover.

“Police are investigating. This is Gillian Murray reporting, National News Radio.”

She could almost hear the lick of glee in her friend’s voice. The two of them had covered the story together for over a year, were both crushed when Markham been acquitted. No one else had ever been charged with Laney Markham’s murder, and the murder of her unborn child.

It had stayed with them both, the terrible injustice of it nagging at them. They looked on with impotent rage as the machine took over—Markham’s inevitable book release, the talk show circuit where he pretended to be tirelessly looking for his wife’s killer. They had to see his face nearly every day, the mask of the wrongly accused man so fake, so painted on, Rain couldn’t see how anyone might believe it.

I used to believe in justice, Gillian said one night over too many drinks. I don’t anymore. Bad people win. They win all the time.

Rain had tried to cheer her up, but how could she? Her friend was right.

She snapped off the broadcast, stared at the jars of baby food. The room swirled around her the way it used to, when a story got its teeth in her.

Someone killed Steve Markham. He got away with murder, until he didn’t. A million questions started to take form. Who, what, when, where? Why? It touched another nerve, too.

Greg came down the stairs, dressed in his workout clothes, holding a garment bag. He was watching her. From the lines of worry etched in his forehead, she could tell he already knew.

“You heard about Steve Markham?” she asked.

“Just got the news update on my phone,” he said, rubbing at the crown of his head. He put the garment bag on the couch, tried for a smile. “You and Gillian should get together and have a toast. Markham finally got what he deserved.”

“Who do you think did it?” she asked.

“You would know better than I do,” he said. His voice was gravelly, soft. She’d never heard him raise it, in all their years together. “The brother. The father. The guy had no shortage of enemies.”

“Lots of people make threats,” she said. “It’s another thing altogether to take someone’s life. Even someone who deserves it.”

She poured him a cup of coffee from the French press, handed him an apple. This was his preworkout breakfast. He’d put on weight during her pregnancy. But he’d lost it all. In fact, he was in better shape now than he had been when they were first dating, the muscles on his arms strong and defined, his body lean. She could not say the same for herself. She tried to squeeze herself into her old jeans the other day and wound up lying on the bed, crying. Had she ever fit into them? It seemed impossible.