Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Baking Made Easy»

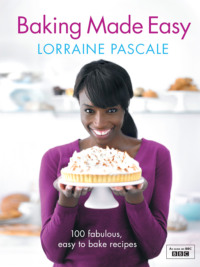

Baking Made Easy

Lorraine Pascale

100 Fabulous, Easy to Bake Recipes

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Lorraine’s Baking Tips

Chapter 1: Breads

Chapter 2: Cakes

Chapter 3: Savoury Baking

Chapter 4: Desserts & Patisserie

Chapter 5: Dinner Party

Chapter 6: Sweet Treats

Chapter 7: Basics

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

My earliest baking memory is one of me at primary school. I am five and carrying a battered old tin which contains the precious ingredients to make raspberry buns. My cookery teacher is an unexpectedly beautiful woman who looks like Marilyn Monroe. In those days, we had to provide all the ingredients – and we loved to mix and whisk vigorously – just like grown ups. We’d end up with these little rock-hard balls of dough that we’d artfully filled with raspberry jam. What an amazing feat to bake something all by yourself and then to eat it and share it proudly with your family. This was the first time I remember really appreciating food – and it was all down to baking. These classes only came round once a term but I looked forward to them more than anything else. So it was inevitable that my first cookery book would have an emphasis on baking. Writing this book really is a dream come true for me.

My heroes have always been the great female food writers Elizabeth David, Fanny Cradock, Isabella Beeton and Marguerite Patten – all extraordinary culinary visionaries whose influences are still prevalent today. Just like them, I have always wanted to find that ‘work thing’ I could feel passionate about. I enjoyed my modelling days, but I knew that it wasn’t the thing I was destined to do for ever. I was briefly a secretary, then a mechanic, an interior designer – I even wrote a book about football’s offside rule! But nothing held my attention for long. And then, by chance, I enrolled on a diploma cookery course at Leith’s School and I knew at once I was home.

I had fallen head over heels. Friends readied themselves to tease me yet again about another failed venture but this time I surprised them all. I just kept on going with the course and I ended up studying cookery, specialising in patisserie, for over a decade. I cut my teeth working in some of the country’s most respected kitchens and I worked alongside chefs who were completely committed to the pursuit of culinary perfection.

Looking back at my life, with its inevitable highs and lows, I now realise that I have always found a sense of purpose and a strength of mind when I am in the kitchen. The phone will ring and dramas will unfold outside, but cooking is where I find my peace and quiet. Time feels like it’s standing still when actually it is flying by. I believe this is called being ‘in the flow’ – when you are so passionately and happily engaged in an activity that you lose all track of time.

In my first book I wanted to offer a series of recipes to showcase the magical chemistry of baking. Recipes that would stimulate the most sophisticated of palates, but also inspire those of less-experienced bakers. My book contains a hundred of my favourites and includes both sweet and savoury, from Fig, Cream Cheese & Mint Tart and White Chocolate Pannacotta, to Trout en Papillote with Sauterne and Almonds. There’s my take on the Doris Grant Loaf, a delicious Gorgonzola & Pear Soufflé, my famous Stout & Stilton Bread Rolls, and a very wicked ‘I just don’t give a damn’ Chocolate Cake. There are simpler ideas too, like my Glam Mac & Cheese and some Totally Lazy Sausage Rolls.

I have included a whole chapter of bread recipes, because I love making bread. It must be the physical process of rhythmically kneading a compliant dough that makes it one of the most therapeutic of activities. There is an almost religious experience to be had from thoughtfully crafting a loaf and then eating it warm from the oven. Think of delightfully aromatic foccacia from Italy – salty, oily and fragrant, or a sophisticated and discerning French fougasse that is mature enough to support the flavours of molten cheese and piquant ham. Crumbly and cake-like Irish soda bread, slapped with really good butter: I dream about this. With bread, the possibilities are limitless and I’ve included new twists on many favourites.

My book would not be complete without plenty of recipes devoted to a very special ingredient – chocolate. A product so universally adored, debated and eaten deserves special attention. I wanted to give you recipes that were delightful to prepare, beautiful to gaze at, dreamy to eat. Chocolate Melting Puddings and the Chocolate & Hazelnut Tart tick all the boxes, and there’s my glorious ‘I can’t believe you made that cake’, a mountain of chocolate cigarillos and strawberries. For all true chocolate brownie aficionados, I believe I have formulated the perfect recipe – a brownie that is light in texture, high in taste and substantial in the eating.

I hope I have written a book that will stand the test of time. A book that you will not only look at and admire, but will use, again and again and again. A book that comprehensively covers all the classics, but dares to give them a twist, that sits between practical and inspiring. These recipes will take you comfortably from Monday to Friday – with enough treats besides for special occasions and those precious weekends.

Have I inspired you? I sincerely hope so. Shake out your apron, switch off that phone, shut the kitchen door firmly and ramp up the music…because now is all about baking!

Lorraine’s Baking Tips

Choosing your ingredients

Medium-sized eggs are used in all my recipes. A whole medium-sized egg weighs approximately 55g (2oz). A medium egg white weighs approx. 30g (1oz). So if you only have eggs of a different size in your kitchen, crack them into a jug and mix well, then measure out 55g for each whole egg required.

Most of my recipes use unsalted butter. However, a good-quality salted butter is okay to use (beware – the cheaper the butter, the more salt it contains). If using salted butter in cakes, omit any extra pinches of salt that are requested in the recipes.

I rarely use self-raising flour. Instead, I use plain flour and baking powder, which gives you more control over how much the cake will rise.

A good vanilla extract can make all the difference to a recipe, but for the best taste, use the seeds from actual vanilla pods. These are extremely expensive in the supermarkets, so if you do lots of baking, vanilla pods can be purchased in bulk on the internet. Instead of paying £3 for just two pods, buying in bulk can work out at as little as 12p per pod!

I never buy unwaxed lemons as they are so expensive, and not always readily available. For zest, buy ordinary lemons and wash them well in hot, soapy water. Give them a good rinse, rub them dry and the waxy coating will come off.

Tips for better baking

• Preheat your oven prior to weighing out any ingredients.

• Have all ingredients at room temperature for the best results, apart from when you need egg whites. Warm eggs are much harder to separate than cold ones, so cold, fresh eggs are best.

• Take your butter out of the fridge as soon as you get an urge to bake, as so many of my recipes call for soft butter. I’ve tried all sorts of not-so-clever quick melting solutions for too-hard butter, such as sitting it on a radiator, or placing it near the stove, but the one I fell in love with was grating it with a cheese grater into a bowl. The butter becomes instantly soft and ready to use. Genius!

• There is no need to sift flour, unless it has really clumped together or the recipe specifically states it.

• Icing sugar is normally best sifted as it does tend to clump together and may leave lumps in your buttercream.

• If possible, invest in some proper measuring spoons – a teaspoon and tablespoon are most commonly needed. These are available in most bigger supermarkets, from cookshops or online.

• When folding ingredients together, the best tool is a plastic spatula rather than a metal spoon (although this will do). Always fold the mixture slowly to retain as much air as possible.

• For safe and effective chopping, put a damp kitchen cloth underneath your chopping board to stop it sliding around.

• If attempting a pastry recipe, be aware that they aren’t the fastest recipes in the world and due to their precise nature should not be hurried. Leave yourself plenty of time.

• When flouring a board or surface for rolling pastry, make sure there’s enough flour to prevent the pastry sticking, but don’t use so much that it changes the quantities of the recipe!

• For best results, do use the size of tin or dish recommended in the recipe.

• The best way to grease tins and pans is with the vegetable oil spray often used for low-fat frying.

• Bake cakes on the middle shelf of the oven at 180°C (350°F), Gas Mark 4 unless the recipe states otherwise. Bread should be baked in the top third of the oven, while meringues need to be put near the bottom. (For meringues, you can also leave the oven door open just a fraction, which allows moisture to escape.)

• Every oven is different, so cooking times can often vary. If opening the oven to check something’s cooked, open the door, take out the item and then close the oven again quickly so that the heat does not get lost.

• To test if a cake is cooked, insert a skewer or cocktail stick into the centre of the cake – it should come out clean.

Tips for great bread-making

• If you do it right, bread-making can be the easiest thing in the world. For the very best loaves, fresh yeast is the way forward. But after it proved a challenge to buy in central London, I thought it prudent to suggest fast-action dried yeast for the recipes in this book. I know many people might have a bread maker – indeed, I was the owner of one for a spell – but I missed the tactile and magical experience that comes with being able to see every stage of the bread-making process, and I’m now a firm believer in making it by hand.

• Be brave with the water: the wetter the dough, the fluffier and lighter the loaf will be.

• Always measure out the salt precisely, as this one ingredient makes all the difference between a good-tasting loaf and a bad one. And be warned that lo-salt, whilst brilliant for other dishes, does not work well when making bread, because it doesn’t impart enough flavour and the bread will end up tasting bland.

• Accurately time the kneading process and knead the dough for the full time stated in the recipe. It really does make a difference.

• When leaving the bread to rise, it likes to be in a warm but not hot place. Most airing cupboards and tops of radiators are too warm. A warm, cosy kitchen is usually just fine.

• To test if the bread has risen enough, flour your finger and gently prod the side of the loaf. When ready, the dough should spring halfway back up.

• Once a loaf is ready to bake, there are a number of ways to ‘glaze’ it. Milk will give it a soft, matt look; eggwash will give a shiny, crunchy look; and sieving a little flour over the top will give it an authentic rustic ‘French bread’ look.

• Try to create a steamy environment inside the oven – this will give the bread plenty of time to rise up before the hard crust starts to develop. Throw some ice cubes into the bottom of the oven, use a water spray to create a mist, or put a roasting tin, half filled with water, on the bottom shelf.

• If the top of your loaf is done but the bottom is not (to check, turn it over and tap it. If ready, it will sound hollow), cover the loaf loosely with some foil to prevent it from colouring further while it finishes cooking.

Chapter 1: Breads

If you’re lucky enough to live near a good patisserie or deli, you’ll know what an amazing array of breads they have on show. When I have time, I find great comfort in making my own bread, and whether you’re a novice or are well-practised in bread-making, there will be something for you here. Soda bread comes top for ease of making, while the fougasse needs slightly more effort and skill. Whichever recipes you choose, if you follow the instructions to the letter, you’ll end up with a loaf to be proud of.

‘Blues is to jazz what yeast is to bread. Without it, it’s flat.’

Carmen McRae

Jazz vocalist and pianist 1920 – 1994

Croissants

A humble breakfast pastry or the king of Parisian patisserie – how did the simple croissant become so famous? The homemade version is quite different to the ones widely available in supermarkets. Admittedly there is a high degree of fiddlyness required to create this most perfect of crescent-shaped delights (and let’s not dwell on the mountain of butter involved…). However, my recipe is speedier than other croissant recipes and the taste and texture are in sharp contrast to the soft, insipid variety you will have previously eaten. Makes 12–14

310g (11oz) strong white bread flour

165g (5½oz) plain flour, plus extra for dusting

2 tsp salt

60g (2½oz) soft light brown sugar

1 x 7g sachet of fast-action dried yeast

40g (1½oz) butter

250ml (9fl oz) water

230g (8¼ oz) block of butter, softened

Vegetable oil or oil spray, for oiling

1 egg, lightly beaten, for glazing

Put the flours, salt, sugar, yeast and 40g (1½oz) butter in a large bowl. Using your fingers, rub the butter into the mixture until it resembles fine breadcrumbs. Add the water and stir with a knife to bring the mixture together. Gently knead for less than a minute to a smooth ball. For croissants, unlike most bread, it is important that the dough is ‘worked’ as little as possible at this stage. Wrap it in clingfilm and leave in the fridge for 1 hour to rest.

Once the dough has been ‘rested’, roll it out on a well-floured surface to a rectangle no larger than 20 x 20cm (8 x 8in). Place the block of softened butter in the middle of the dough. The butter needs to be the same softness as the dough. Fold up the edges of the dough over the top so they overlap and completely cover the butter.

This next process is called rolling and folding, or ‘turns’, and it creates the characteristic flaky layers of a croissant. Keep the work surface well floured so the dough does not stick. Roll out the dough to a rectangle 3 times as long as it is wide, about 45 x 15cm (17¾ x 6in). Make sure it is rolled uniformly so the butter is spread out evenly inside.

Place the dough with the shortest end facing you. As if you were about to step out on a red carpet. Take the end nearest you and fold it into the centre. Then fold the top third down so the two ends now meet in the middle. Turn the dough 90° to the left and then repeat this step. Wrap the dough in clingfilm and put in the fridge for an hour to rest. You have now given the dough two ‘rolls and folds’.

Remove the dough from the fridge and give the dough one more ‘roll and fold’ by rolling it out to 45 x 15cm (17¾ x 6in) again and folding the ends into the middle as before. Then roll it out to a rectangle about 35 x 14cm (14 x 5½in). Place the dough on the baking tray, cover with oiled clingfilm and leave to rest in the fridge for 1 hour.

Put the dough on a lightly floured work surface and trim any ragged edges with a sharp knife, then cut the dough in half lengthways. Cut each strip into triangles, each with a base of about 6cm (2½in) and two longer sides, 8.5 x 8.5cm (31/3 x 31/3in), going up to the point. You may have some trimmings left over. Place each triangle on the work surface with the longer point towards you and roll up the triangle away from you so that the tip folds over the top. Place them all on the baking tray and carefully curve into crescent shapes. Make sure the croissants are spaced well apart to allow them to expand during cooking. Cover with oiled clingfilm and leave to rise in a warm place for 1 hour.

Preheat the oven to 200°C (400°F), Gas Mark 6.

Brush the croissants lightly with the lightly beaten egg and bake in the oven for 15 minutes, or until golden brown. Remove from the oven and leave to cool on a wire rack.

Mascarpone & brown sugar

Scones

The unusual use of mascarpone and light brown sugar in this recipe makes these scones extra rich and a cut above the regular type. Makes 9

340g (12oz) self-raising flour, plus extra for dusting

1 tsp baking powder

Pinch of salt

80g (3oz) butter, cold and cubed

2 tbsp soft light brown sugar

80g (3oz) mascarpone

About 90ml (3fl oz) milk

1 egg, lightly beaten, for glazing

Preheat the oven to 210°C (415°F), Gas Mark 6–7. Dust a large baking tray with flour.

Put the flour, baking powder, salt, butter and sugar in a food processor and pulse until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. Add the mascarpone, then pulse again for 3 seconds. (If you don’t have a food processor, put all the ingredients in a medium bowl, pick up chunks of butter covered in flour and rub them between your thumbs and forefingers. Add the mascarpone and continue ‘rubbing in’. This shouldn’t take more than about 5 minutes.)

Pour the mixture into a large bowl and make a hole in the centre, then pour in enough milk to make a soft dough and stir with a knife. Use both hands to bring the mixture together, and squeeze, making sure any dry bits get picked up. It may seem like a crumbled mess but keep squeezing and the dough will come together. Knead lightly for a few seconds just to make the dough smooth and then roll out quickly on a lightly floured surface to about 2cm (¾in) thick.

Cut out rounds using a 6cm (2½in) round cutter (though any size will do) and place them on the prepared baking tray. It’s important not to twist the cutter whilst doing this or the scones won’t rise evenly when baked. Squish together any leftover dough, roll out and cut out more scones.

Brush the tops with beaten egg and bake in the oven for 10–12 minutes, or until the scones are nicely risen, firm and golden brown. Remove from the oven and leave to cool a little on the tray. They are best served fresh and warm from the oven with lashings of clotted cream, strawberry jam and a pot of tea.

Brioche Rolls

The easiest way to make brioche is in an electric mixer with a dough hook. You can make it by hand, but you’ll need some time and a whole heap of patience. As an alternative to a brioche mould you can use a deep muffin tin. For a variation, soak some raisins in Madeira for an hour, dry them well, toss in flour (to stop them from sinking during baking) then add them to the dough once all the butter has been added. Makes 12

Vegetable oil or spray oil, for oiling

500g (1lb 2oz) plain flour, plus extra for dusting

1½ sachets of fast-action dried yeast (10g/1/3oz)

2 tsp salt

3 tbsp soft light brown sugar

6 cold eggs, lightly beaten

310g (11oz) butter, softened

1 egg, lightly beaten, for glazing

Equipment

12 mini brioche moulds or a 12-hole deep muffin or cupcake tin

Oil the moulds or muffin or cupcake tin.

Put the flour in an electric mixer with the yeast, salt and sugar. Add the eggs, two at a time, mixing well between each addition on a slow speed. Once the eggs are all added, mix for 8 minutes. With the mixer still on a low speed add the butter in 5 additions, making sure that each bit of butter is well mixed in before the next is added. Every couple of minutes or so, scrape the sides of the bowl down with a spatula to make sure that all of the dough is fully mixed in. This process of adding the butter takes a good 10 minutes on the machine. The mixture will go from a stiff ball of stretchy hopelessness to something silky and smooth once all the butter is incorporated.

Once all the butter has been added keep mixing it until the dough no longer sticks to the side of the mixing bowl.

If you are doing this by hand the dough will look like a big runny sticky mess initially and keep sticking badly to the work surface. Just keep pulling the dough up and then pushing it down and scraping it off the work surface so you are continuously stretching and moving it. Eventually the dough will become less sticky, more elastic and begin to be a little easier to handle. It is tempting to throw in more flour so that it is less sticky, but doing this will change the brioche recipe altogether and make it more like regular bread. This may take up to 20–25 minutes or more. The dough will still be very soft at this stage.

Once the dough is ready, divide it into a third and two-thirds. Take the larger piece and divide it into 12 equal pieces. With well-floured hands take one of the pieces and make a ball with it, push it down into the mould or tin, then with a floured finger make a big hole in the middle. Repeat with the rest of this piece of dough. Then take the smaller third piece and break it into 12 portions. Roll each one into a bullet shape so it has a round ball at the top and a long pointed end. Push the pointed end into the hole all the way down so only the top third of the bullet is showing. Repeat with the rest of the dough. Alternatively, if by this stage you have had enough of your brioche, which, believe me, can happen, you can freeze it for up to a month by wrapping in clingfilm or putting it into a freezerproof bag and come back to it another day once it is defrosted and you are ready to conquer it again.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.