Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

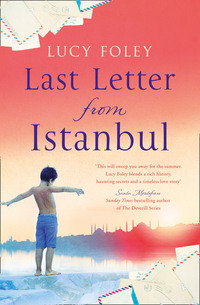

Kitabı oku: «Last Letter from Istanbul», sayfa 2

CONSTANTINOPLE

1921

The Boy

From the window he watches Nur hanım leave, rounding the end of the alleyway onto the larger thoroughfare with its thronging crowd. Funny, she always seems to him such a powerful person. But now he sees that compared to other adults she is not large at all. In fact she is dwarfed by many of them, and by the great bag of embroideries at her hip that causes her to stagger slightly beneath its weight. In some complicated way this worries him. He watches her now as though his gaze were a cloak that might keep her from harm, until she is lost to sight.

He knows exactly what he will do now, and it does not involve reading his schoolbooks.

He is hungry all the time. When the war came the city forgot how to feed the people that lived in it. Once food was everywhere. A different smell around every street corner: the sweet yeast of simits, piled high and studded with seeds, the brine of stuffed mussels cooked on a brazier, of fried mackerel stuffed into rolls of bread, the aroma of burned sugar drifting from the open door of a pastane, even the savoury, insubordinate tang of boiled sheep’s heads.

Sometimes it was enough to merely breathe in these scents, so powerful that if one came close enough it was almost like tasting them. Sometimes one found it necessary to part with a few emergency piastres – only to be used in the case of direst need – and share a warm simit with one’s friends on the way to school.

The pride with which the sellers displayed their wares: fresh-shelled almonds arranged by the bademci – the almond seller – upon a shimmering cake of ice; the sour green plums, that one could only eat for twenty days of the year, carefully arranged in small paper bags. A towering pyramid of plump tomatoes, smelling and tasting of the sun itself.

When the war came, these vanished. Not at once. In the first weeks there was just a little less. The street food went first, fading from the city like the detail from an old painting. Then the bakeries. In the beginning the bread was a day old. Then a week, then two weeks. Then it disappeared altogether.

In the burned place he did not eat for three days. He stayed in the dark, and waited for it to take him. When she found him he could not have walked out of there on his own – he hadn’t the energy to lift his head from the floor. Now it is like the hunger has found its way deep inside him, has put down roots. Even now, when there is more to eat, even now it remains. Even after he has eaten it is there, gnawing at his insides. He thinks about food constantly; he dreams of it.

The other women are in the other room: the old one, and the one who never speaks. From beneath the door comes the scent of tobacco. It smells of burned things. It speaks of the time before. He will not think of that. The important thing is that they are busy. This leaves him free to explore the kitchen.

These searches are never particularly rewarding. An old onion, perhaps, aged to softness. Eaten like an apple. The memory of it in the mouth had the exact odour of a man’s sweat. Or perhaps a heel of bread, with a white-green bloom of mould. Cobwebs, too, if it has fallen into some hard-to-reach place from which only an arm as thin as his can extract it.

But now, reaching further into the dark recess than ever before, his fingers brush a new object. He draws it out, mildly curious. A book. This is not of any particular interest; it cannot be eaten. Books are school, and difficulty. In its favour, though, is the fact that it had been discovered by him alone.

‘Hello,’ he says.

There is mystery attached to it. He takes it into the patch of light spilling from the street lamp to look at it. It is homemade, not printed, written in a hand somehow familiar to him. No pictures – this is a disappointment. He has little time for words. He knows that he is clever, but words can outwit him, can shift before his very eyes.

He stares at it for a few minutes, hardly bothering to puzzle it out, ready to give it up as a bad job. Then a word makes itself familiar to him, as though the light itself has drawn its meaning up out of the page. Chicken. His mouth floods with saliva. He goes to the next word. Walnuts. It is already, thanks to these two words, the most interesting book he has ever come across.

Concentrating intently, frustrated by his own slowness, he puzzles out the rest of it. Paprika – he knows that, the bright powder made from peppers. The words, he begins to realise, describe a larger whole. A dish. Chicken with Walnuts and Paprika. He can imagine it, yes. He closes his eyes and summons the flavours with a great effort of imagination. The tender flesh of the meat, the bitter of the nuts, the sweet smoke of the spice.

The idea of the dish in his head is a kind of pleasurable agony. It is almost as good as eating it. Of course, one does not have the fullness in the belly afterward. But he hardly ever has that anyway, cannot remember a time when he has felt fully sated by what he has been given to eat.

Now the magic of this imagined meal is used up.

He turns the page, to discover the next delight. Chicken – easy, he had the shape of the word in his mind now. Chicken with … he squints at the word. Figs. That is the best time of the year, when the tree in the schoolyard yields its fruit. In the time of worst hunger they had been everything to him. Less filling than bread, but more so than the aubergine skins he had scavenged from the bins. There are two kinds: white and purple. The latter are bigger but the white are finer-flavoured. Tiny, fragrant morsels. They are his favourite. Unfortunately they are the birds’ favourite too. He was almost tearful with frustration, upon leaving lessons, to discover that they had got to so many of them before him. And they were so wasteful. They would eat part of a fruit, and leave the rest hanging upon the branch to dry out or rot. They would scatter half of what they stole upon the ground. He would eat these remains, or collect them in his pockets.

He reads on, his mouth wet with longing, his stomach protesting, his mind filling with impossible fantasies.

Nur

There are difficult negotiations with the linen buyer. ‘Every week I have another woman coming to me with a story like yours, hanım. Great families who have lost everything, fallen on poor times. And all their work is beautiful.’

‘But I came to you first – that must count for something?’

He seems not to have heard. ‘The Russians! They come to me straight from the ships laden with great bundles on their backs: silks from Paris, the finest cashmere shawls. They are such poor wretches now: no homeland, no future. You must count yourself lucky. There are others who are far more unfortunate. We have all lost a great deal.’

It is true. Every day new inhabitants arrive, fleeing the ongoing consequences of the Great War, the revolution in Russia. Dispossessed, desperate. Regular flurries of chaos at the quays: vast carriers arriving with human cargo. Some filtered into the system of Allied camps. Others absorbed by the city, disappearing with little trace. But she hopes that he sees the long look she gives his stall, occupying four times the space it once did; the smartly refurbished sign with its gilt lettering, the beautiful new silver samovar from which he has declined to offer her any tea.

As she leaves the bazaar she sees the Allied soldiers, buying trinkets. It is not enough for them to have occupied this place; they want to take a piece of it back with them. A souvenir. A war trophy. Exotic, but harmless, like a muzzled dancing bear. Her linens will be stowed in trunks, will make the long journey back across the breadth of Europe to decorate sideboards and tables in houses in London and Paris. She likes, in more optimistic moments, to think of this as a colonisation of her own.

Their uniforms are clean but she sees them drenched in blood. How many men have you killed, she asks, silently, of some sunburned boy as he holds a fake lump of amber up to the light with an unconvincingly expert air. And you? – of the fat officer fingering women’s sequinned babouches – did you slaughter my husband, at Gallipoli? My brother, in the unknown wasteland in which we lost him?

She thinks of Kerem, her lost brother, every day. There are reminders of him, everywhere – particularly in the schoolroom where it should be he who stands in front of the pupils, not her. But it is more visceral than that: it exists in her as a deep, specific ache, as though she has lost some invisible but vital part of herself.

With the loss of her husband, it is different. She can go whole days without thinking of Ahmet – and then remember with a guilty start. It is not that she does not care, she has to remind herself. It is that all of it – him, herself as a bride and then briefly as a wife, the night that followed – all seem abstract, intangible as a dream. Once she found herself rooting through the chest of clothes in the apartment, desperate to find her wedding outfit. She thought the sight of it might make her feel the grief she was supposed to feel. Because she grieves him only as she might the loss of a stranger. But then that was what he had been – even in those two weeks as husband and wife before he left for the front. When she thinks of Ahmet she thinks, with genuine sadness: how terrible for his mother. What a waste of young life. She does not think of it, not at first, in relation to herself. What sort of a widow does that make her?

On the ferry back she stays on past the stop at Tophane where she would normally disembark for home. As they cross the great channel of the Bosphorus she watches the shore of Asia approach and feels her skin prickle like someone about to commit a crime. Upon the opposite bank, growing visible now, is the white house.

She should not do this. She knows no good can come of it. A destructive thing. This instinct of hers, however, has overwhelmed reason.

The worst thing was that they took it, and did not use it. The final insult, to leave it gathering dust, like the skeleton of one denied the burial rites.

Her father – in his whimsical way – once described the house as a woman who had lain down beside the water for a rest that had become endless slumber. This idea, as with certain things heard in childhood, ignited in her mind. Even now she cannot help but see the sleeper, the cluster of trees that form her wild dark hair, the small jetty her hand trailing through the water. Nur feels, looking at her, a sense of betrayal. What luxury might it have been, to have slept through all of this without the least concern? She feels the same way about the stray cats she feeds. When she sees the tortoiseshell tom stretch himself out on the sun-kindled tiles of the roof opposite she knows that she is witnessing a contentment that for any human, especially one living here, would be impossible to obtain.

Her eyes never leave the house. As the ferry shudders its way toward the dock of the station she is certain that she catches a movement in one of the downstairs windows. This is impossible, of course – it must have been a reflection. It has remained empty, useless, all this time. Still, the animal part of her mind has been worried by it, and she finds herself watching for more movement. She thinks it was in the haremlik, the women’s quarters, the domain over which her grandmother presided like a queen. Well. There are so many memories confined in there that perhaps she really did see some flicker of the past.

As she alights, she feels exposed on the quay, imagining how she might appear to someone who knows her, what they would guess of her mission. That they might pity her – that is the worst of it. Far worse, certainly, than the censure they had shown previously. Her dead father’s innocence has been all but proven by the fact that the occupiers have done nothing to recognise or reward the family. What more did they have to lose to prove their support for the cause? A son lost, a daughter widowed … what more had to be sacrificed before they were considered free of suspicion?

For the first time in a long while she rather longs for her veil, for the shield of it. She keeps her head lowered, and at the same time detests her own cowardice. There is nothing shameful in what she is doing, only a little sad.

The path to the house, the private one through the trees and bushes immediately beside the water, has been exposed. Nur would have thought the thicket would have closed itself around it by now in an impenetrable tangle. In fact, had some self-preserving part of her hoped that she would be forced to turn back at this point? Now she must continue with the thing, see it through.

Here, too, are unexpected assaults of memory: scents of wild fig, olive, blue mint, bracken, mingling with the brine of the water. A pressure in her chest, a knot of tears that will not be shed, that cannot be relieved.

There is less magic in it up close than viewed from the water. Now visible are the places where the white paint is beginning to peel from the old grey wood beneath, how the elderly balconies sag with the weight of more than a century, that in the eaves of the roof are the fragile remains of birds’ nests from years gone by. Yet these flaws, for Nur, are as tenderly observed as those in the face of a loved one.

She is close enough now that she can hear the effect of the water in the boathouse, the strange echoes: the gargle and slap. The accompaniment to hours sitting on the little jetty reading a book, casting a line out to catch fish as her father had taught her – she was better at it than her brother. When she did land one, however small and spiny, Fatima would take great care to serve it at the next meal, transformed with lemon and parsley and tender cooking over fragrant wood. As a child she had sat on that platform with her ankles and feet submerged in the water, instantly cooling on a hot day. She is caught by the idea of it, it grows inside her. There is no one here to see. She makes her way down the stone steps, onto the wood of the platform, lowers herself until she is sitting, slips off her shoes and extends her bared feet into the water.

Sometimes, now, the old life seems as remote as one read about in a book. But this afternoon it seems very close at hand, an assault of memory. If she refuses to look at the great grey warships marshalled further downstream she can almost persuade herself that she is sitting here suspended in her past.

How old is she? She thinks. She is in control of this fantasy, she can choose. Twelve. The time before anything became complicated. Before talk of marriage, or propriety, before illness and death. She has just climbed a tree … it has left her hands and feet sticky with sap. She will wash them, here, in the waters of the Bosphorus before she casts out her fishing line.

The older women will be sitting in the women’s quarters, the haremlik, after a lunch of several courses. Perhaps they have friends visiting them from the city, in Parisian gowns that sit oddly with their veils. Or perhaps they have come from further afield, from Anatolia, traditional in loose silks, their fingernails stained with red dye. By now they will be deep in gossip. Or perhaps they have summoned a female miradju to entertain them all with tall tales. Most of these professional storytellers rely upon a carefully honed set of stories, most known fairly well to their listeners, yet still pleasing because of the unique style and flourishes of the teller. But the very best of them can invent narrative upon the spot, conjuring people and places straight from the imagination.

Once Nur told her mother that her greatest ambition was to become one of these women – and received a lecture on the importance of knowing one’s class. These women were still salespeople – no better than the simit sellers or the rag women – even if their currency was words.

Footsteps, behind her. Her father, come to join her in her fishing. Or perhaps he has brought with him the backgammon set, inlaid with ebony, ivory and mother-of-pearl. She turns.

Behind her, at the top of the steps, stands a man in a white robe, a pipe dangling precariously from his open mouth. A lit match burns unattended in his hand, forgotten in his surprise.

‘By Jove,’ he says, stepping quickly backward. And then, as the flame from the match climbs high enough to lick his fingers, ‘Ouch!’

An Englishman, half-dressed, here on the Asian side of the water. None of this makes any sense to Nur: she thought, hoped, that they were confined to Pera. He stares, she stares back. They are like two street cats, she thinks, watching one another warily.

‘By Jove,’ he says again, under his breath, as though the important thing is to say something – that by doing so he will wrest some control over the situation. Nur is standing, attempting to retrieve her slippers with furtive movements of her feet. She risks another quick glance. She has never seen an Englishman – indeed any man – dressed in such an outfit. It is a longish, very loose, very thin white shirt; if she were to allow herself to look properly she would realise that it does not quite preserve his modesty.

‘Well,’ he says fiercely, ‘what the devil are you doing here?’ He has made his pitch for the upper hand, she realises. ‘You don’t understand me, do you?’ His pride has marshalled itself. ‘This is private land. Private. Be gone with you …’ He raises an arm, imperious, points in the direction of the path. ‘Shoo!’

‘I suppose I might ask you the same question.’

He takes a step back.

She has learned this, especially in that time since the occupation began: to wield language, her command of it, as an instrument of power.

He shifts onto his other foot – and for a moment he seems to teeter. The surprise seems to have taken all the force out of him. He looks rather pale, she thinks, even for a pallid Englishman – there is a frailty that she had failed to see before, distracted by his odd attire and her surprise.

Now another figure is approaching, from the house. He is properly dressed, in British army khaki. Her stomach clenches. It is now that she becomes aware that she is effectively trapped on the jetty: these men on one side of her, the water on the other. She will stand her ground; she has done nothing wrong, after all.

There is something familiar about him, this other man. He, too, seems to be experiencing some struggle of recognition. He frowns. His eyes travel from her face to her bare feet, and back again. ‘It’s you. The woman with the books.’

Yes, she does recognise him. Not the face so much as the voice. But she will not give him the satisfaction of admitting it; in refusing she will retain the upper hand. ‘I do not know what you refer to.’

He frowns. ‘You don’t remember? Just two weeks ago … past the Galata bridge. I’m sure it was you. You dropped …’ a pause, then, in triumph, ‘a red notebook!’

A week ago. She was late, on her way to the school. There were painful negotiations with the linen buyer, who tried to convince her that the trade had reached saturation, and he could only offer a third of the usual price. She had to go through the whole charade; to turn on her heel and march away from him before he called her back. This had wasted a good quarter of an hour that she did not have spare.

She could imagine chaos in the classroom already – it seems to unfold even when her back has been turned for a minute, even now there are so few of them. Nur rather loves them for it. But now dread visions appeared before her: desks overturned, ink spilled.

She could not go fast enough. The cobblestones in that part of town are lethal, especially if one is in a hurry. Every third step seemed to be an awkward one, sending her pitching forward as though she might fall. She had felt a building irritation. There was nothing to direct it at other than the men who had laid these uneven stones at some unknown time in the past. But it grew, to a low-level anger at this city in general. Where everything and everyone seemed suddenly world-weary, broken. There was too much history here, too many lives and ages layered one over the top of another. How could one ever hope to grow, to move forward, with this ever-present, melancholy, hot-breathed closeness of the past?

She heard footsteps behind her.

‘Excuse me?’ In English.

Nur kept her gaze down, hurried her pace. Another misstep; her ankle turned on itself, an arrow of pain lancing up.

‘Bakar mısınız?’

She hesitated, surprised by the Turkish, clumsy though it was. In her moment of hesitation, he had caught up with her.

‘You dropped this.’

She turned. She saw, on looking up, a khaki form, the vague oval of a face. This was all her glance allowed time for; she could not have said with absolute certainty that there had also been eyes, a nose, a mouth. Because the thing about the foreign soldiers is that one does everything one can to avoid looking at them. Not to pretend that they don’t exist; that would be impossible. After three years of occupation they have come to seem as much a part of the city as the thousands of stray dogs that roam its streets. Just like those dogs they have made it their own; taken possession, taken liberties. But one avoids looking at them to avoid trouble. From a man a too-long glance might seem a threat; many have been thrown into Allied prisons on smaller pretexts. From a woman, it might seem an invitation.

She took the thing he was holding out to her, though to do so seemed in itself like a weakness. His fingers brushed hers, an accident, and she snatched her hand. It was her red notebook, the one in which she plans out her lessons. She pushed it beneath her arm with the others, turned, walked away.

She realised after ten more steps that she had not thanked him. Well, she thought. One small act of defiance for the vanquished.

‘It was you, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘It was me.’ If he is expecting her to thank him, he will have a long wait.

He smiles. She thinks how much she would like to hit him, or spit at his feet. ‘How is your ankle?’ he asks.

‘There is nothing wrong with my ankle.’ She hears the edge in her voice. Careful, must not push it too far. He is smiling, but these invaders can turn in an instant. And yet she refuses to show that she is afraid of him, especially here, in this place. ‘Why are you here?’ she asks.

‘This is a hospital,’ he says. ‘I am the doctor here. This man, Lieutenant Rawlings, is one of my patients.’ Then, almost to himself, ‘Who should not be out here, in fact.’ He turns to the robed figure. ‘Why are you out, Rawlings?’

‘I came here to smoke my pipe. Can’t have the damn thing inside – Sister Agnes complains about it.’

‘Well, I would return post haste if I were you, or you will have to answer to her. I think she will find this a worse crime.’

The man seems about to retort, then thinks better of it. Flushing, he extinguishes the pipe and begins an unsteady retreat toward the property. But she sees that he does not enter – he remains on the edge of vision as a silent audience.

‘I’m sorry for the lack of courtesy.’ The doctor’s voice is gentler. ‘We don’t have many visitors here, as you see.’

She knows that this is British dissemble. Some sort of explanation is still required, he is waiting for her to make it. She would not know how to do it even if she felt he deserved one. Instead, she asks, ‘This is a hospital?’

‘Yes. It was a house, originally, the owners have since left.’ Something occurs to him. ‘Perhaps you knew them?’

‘No.’ He is still waiting, she knows, for her explanation. There is nothing threatening in his voice or manner, but then the threat is sewn into the very uniform he wears.

‘I have family,’ she says, ‘a little further down this shore. I knew of the path, I thought I would come this way, along the water.’

He frowns. She is fairly sure he is not convinced. And yet she suspects that his courtesy will not allow him to call her out in the lie.

‘Do you know why this house was abandoned? What happened to the owners? I only ask because it feels as though they did not leave long ago.’

‘I never knew them.’ She draws herself together. ‘If you will excuse me …’ She steps toward him. It is the closest she has ever been to one of them, and she feels the clench of fear again in her stomach.

For the first time he seems to realise that he is blocking her path back to dry land. He steps aside.

She walks slowly back the way she came, not caring that he will think it odd; that if her tale were true she should be walking in the other direction, past the house, not back in the direction of the ferry terminal. Her hands are trembling; she clenches them into fists.

Behind her she hears: ‘Well, that was all rather confounding—’

‘What I’m more confounded by, Rawlings, is why you are still outside.’

It could be worse, she supposes. It could have been turned into a barracks, or a nightclub like those that have sprung up in Pera, the European district. A hospital is at least less shameful than that. But her home has been colonised. All of their memories, the intimate, private life of the family. She feels the loss of it a second time. And that smiling Englishman, with his quizzical politeness. Somehow it would have been better, almost less insulting, if he had spoken to her with the abrupt rudeness of the other man.

Her mind fills with fantasies. She sees herself lunging toward him as he moved aside for her on the jetty. Pushing out with both hands … him toppling backward into the Bosphorus. His imagined surprise is a delicious thing; the indignity of his fall.

She could have run back toward the ferry … before he or that invalid had time to act.

She catches herself. She knows that she could never have done it. Her mother and grandmother, the boy, the school: there is simply too much at stake. Still, it cannot hurt to imagine. The realm of fantasy, at least, is one that cannot be occupied.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.