Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Peculiar Ground»

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright 2017 © Lucy Hughes-Hallett

Lucy Hughes-Hallett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

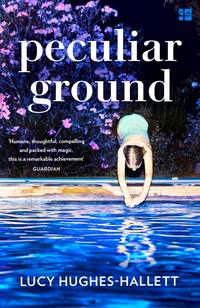

Cover images © plainpicture/Melanie Haberkorn

Cover design by Heike Schüssler

Map drawn by John Gilkes

‘Don’t Fence Me In’ (from Hollywood Canteen), words and music by Cole Porter © 1944 (Renewed) WB MUSIC CORPS. All rights reserved. Used by Permission of ALFRED MUSIC.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008126544

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008126537

Version: 2018-01-16

Dedication

For my brothers,

James and Thomas,

with love

Epigraph

We are a garden walled around,

Chosen and made peculiar ground;

A little spot enclosed by grace

Out of the world’s wide wilderness.

ISAAC WATTS

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Dramatis Personae

Map

1663

1961

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

1973

June

July

August

1989

September

October

November

1665

Author’s Note

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

Dramatis Personae

1663–1665

John Norris – landscape-maker

Arthur Fortescue, the Earl of Woldingham

The Countess of Woldingham, his wife

Their children – Charles Fortescue, Arthur Fortescue and a little girl

Sir Humphrey de Boinville, brother to Lady Woldingham

Lady Harriet Rivers, Lord Woldingham’s sister

Cecily Rivers, her daughter

Edward

Pastor Rivers – brother to Lady Harriet’s late husband

Another pastor

Robert Rose – architect and comptroller

Meg Leafield

George Goodyear – head forester

Armstrong – ranger

Green – head gardener

Slatter – farm overseer

Underhill – major-domo

Lane – steward

Richardson – apothecary

Lupin, a pug-dog

1961–1989

Living at Wood Manor

Hugo Lane – land agent

Chloe Lane – his wife

Nell – their daughter, aged eight in 1961

Dickie – their son, aged five in 1961

Heather – nanny

Mrs Ferry – cook

Wully, a yellow Labrador, and later his great-nephew, another Wully

Living at Wychwood

Christopher Rossiter – proprietor

Lil Rossiter – his wife

Fergus – their son

Flossie/Flora – Christopher’s niece, aged eighteen in 1961

Underhill – butler

Mrs Duggary – cook

Lupin, a pug-dog, and later another Lupin, also a pug-dog

Grampus, a black Labrador

Visitors

Antony Briggs – art-dealer

Nicholas Fletcher – journalist

Benjie Rose – restaurateur, interior designer, entrepreneur

Helen Rose – his wife, art-historian

Guy – Benjie’s nephew, aged thirteen in 1961

On the estate

John Armstrong – head keeper

Jack Armstrong – his son, aged seventeen in 1961

Doris, Dorabella, Dorian and Dorothy – all spaniels

Green – head gardener

Young Green, his son

Brian Goodyear – head forester

Rob Goodyear, his son

Slatter – farm manager

Meg Slatter – his wife

Bill Slatter – their son

Holly Slatter – Bill’s daughter

Hutchinson – estate clerk

In the village

Mark Brown – cabinet-maker

Nell’s fellow students at Oxford in 1973

Francesca, Spiv Jenkins, Manny, Jamie McAteer, Selim Malik

In London

Roger Bates – wartime military policeman, subsequently in Special Branch

1663

It has been a grave disappointment to me to discover that his Lordship has no interest – really none whatsoever – in dendrology. I arrived here simultaneously with a pair of peafowl and a bucket full of goldfish. It is galling that my employer takes more pleasure in the creatures than he does in my designs for his grounds.

He is impatient. Perhaps it is only human to be so. He wishes to beautify his domain but he frets at slowness. When we talked in London, and I was able to fill his mind’s eye with majestic vistas, then he was satisfied. But when he sees the saplings reaching barely higher than the crown of his hat he laughs at me. ‘Avenues, Mr Norris?’ he said yesterday evening. ‘These are sticks set for a bending race.’

The idea having once occurred to him, he set himself to realising it. This morning he and another gentleman took horse and, like two shuttles drawing invisible thread, wove themselves at great speed back and forth through the lines of young beeches that now traverse the park from side to side. There was much laughter and shouting, especially as they passed the ladies assembled at the point where the avenues (I persist in so naming them) intersect, the trees forming a great cross which will be visible only to birds and to angels. I confess the gentlemen were very skilful, keeping pace like dancers until, nearing the point where the trees arrive at the perimeter, where the wall will shortly rise, they spurred on into a desperate gallop in the attempt to outdistance each other, and so raced on into a field full of turnips, to the great distress of Mr Slatter.

They are my Lord’s trees, his fields and his turnips. Like Slatter and his muddy-handed cohort, I must acknowledge the licence his proprietorship gives him, but it grieved me inordinately to find that eleven of my charges, my eight hundred carefully matched young beeches, have been damaged, five of them having the lead shoot snapped off. I attended him after dinner and informed him of the need for replacements. ‘Mr Norris, Mr Norris,’ he said. ‘It is hard for you to serve such a careless oaf, is it not?’

He authorised me to send for substitutes. He is not an oaf. Though it pained me, I took delight in the performance of this morning. He incorporated my avenue, vegetable and ponderous, into a spectacle of darting grace. But it is true that I find him careless. To him a tree is a thing, which can be replaced by another thing like it. Is it lunacy in me to feel that this is not so?

We who trade in landskips see the world not as it is but as it will be. When I walk in the park, which is not yet a park but an expanse of ground hitherto not enhanced but degraded by my work in it, I take little note of the ugly wounds where the earth has been heaved about to make banks and declivities to match those in my plan. I see only that the outline has been soundly drawn for the great picture I have designed. It is for Time to fill it with colour and to add bulk to those spare lines – Time aided by Light and Weather. I suppose I should say as well, aided by God’s will, but it seems to me that to speak of the Almighty in these days is to invoke misfortune. It is more certain and less contentious to note that Water also is essential.

*

Of the people who manage this estate my most useful ally has been Mr Armstrong, chief among my Lord’s rangers. For him, I believe, the return of the family is welcome. He is an elderly man, with the hooked nose and abundant beard of a patriarch. He remembers this house when the present owner’s father had it, and he rejoices at the thought that all might now be as it was before the first King Charles was brought down. I think he has not reflected sufficiently on how this country has changed in his lifetime, not only superficially, in that different regiments have succeeded each other, but fundamentally. It is true that there is once more a Charles Stuart enthroned in Whitehall, but the people who saw his father killed, and who lived for a score of years under the rule of his executioners, cannot forget how flimsy a king’s authority has proved.

Armstrong and Lord Woldingham talk much of pheasants – showy birds that were abundant here before the changes. Armstrong would like to see them strut again about the park. He has sent to Norfolk for a pair, and will breed from them. For him, I think, I am as the scenery painter is to the playwright. He is careful of me because I will make the stage on which his silly feathered actors can preen.

For Mr Goodyear, though, I am suspect. He is the curator of all of Wychwood’s mighty stock of timber. The trees are his precious charges. Some of them are of very great antiquity. He talks to them as familiars, and slaps their trunks affectionately when he and I stand conversing by them. I do not consider him foolish or superstitious: I do not expect to meet a dryad on my rambles, but I too love trees more than I care for most men. Goodyear is loyal to his employer, but it seems to me he thinks of those trees as belonging not to Lord Woldingham but in part to himself, his care for them having earned him a father’s rights, and in part to God. (I do not know to which sect he is devoted, but his conversation is well-larded with allusions to the deity.) He is ruddy-faced and hale and has a kind of bustling energy that is felt even when he is still. I will not enquire of him, as I do not enquire of any man, which party he favoured in the late upheavals, but I think him to have been a parliamentarian.

Today I walked with him down the old road that leads through the forest to the spring called the Cider Well. The road is still in use, but very boggy. ‘His Lordship would like to close it,’ said Goodyear. ‘I suppose he may do so if he wishes,’ I said. Goodyear made no reply. I have heard him allude to me as ‘that long lad’. I think he has judged me too young to be competent, and too pompous to be companionable.

Passing the spring, we dropped down into a valley, its mossy sides bright with primroses. The rabbits had already been at work on the new grass beneath our feet, so that the track was pleasant to walk upon.

A woman I had seen before – old but quick of step – was walking ahead of us. Goodyear called to her. She looked back over her shoulder, nodded to him, and then darted aside, taking one of the narrow paths that slant upwards, and vanished among the trees.

‘You know that person?’ I asked.

‘I’d be a poor forester if there were any soul in these woods without my knowledge.’

I ignored his pettish tone. ‘Does she live out here, then?’

‘She does.’

‘I encountered her in the park on Sunday. She made as though she wished to speak to me, but thought better of it.’

‘It’s best so. Don’t let her bother you, sir.’

I let the matter rest and began to talk to him of the plans I have discussed with Mr Rose, the architect. Rose is one of the many Englishmen of our age who, following their prince into exile, have grown to maturity among foreigners. There are constraints between such men and those of us who stayed at home and picked our way through the obstacles our times have thrown up. Rose and I deal warily with each other, but our work goes on harmoniously. In Holland Mr Rose interested himself in the Dutchmen’s ceaseless labours to preserve their country from the ocean to which it rightfully belongs. My Lord calls him his Wizard of Water.

We would build a dam where this pretty valley debouches into a morass, and thereafter a series of further dams. Thus contained and rendered docile, the errant stream will broaden into a chain of lakes. The three upper lakes will lie without the wall, as it were lost in the woods. The last watery expanse will be within the park and visible from the house, a glass to cast back the sun’s light and duplicate the images of the trees clumped about it.

It was as though Goodyear could see at once the prospect I sketched with my words, and soon we were in pleasant conversation. Willows, judiciously positioned, he rightly said, would bind the dams with their roots, and red alders might give shade. The ‘tremble-tree’, he suggested (I understood him to mean the aspen, a species of which I too am fond), ranged along the watery margins, would give a lightness to the picture, and his tremendous oaks, looming on the heights above, will take off the brashness of novelty, so that my lakes will glitter with dignity, like gaudy new-cut stones in antique settings.

How gratifying it would be to me, if I could enjoy such an exchange of ideas with his Lordship!

*

I could wish nutriment were not necessary to the human constitution, but alas, whatever else we be (and my mind swerves, like a wise horse away from a bog-hole, to avoid any thought that smacks of theology), we are indisputably animals, and animals must eat. My situation here is agreeable enough when I am in my chamber. In the drawing room – where Lord Woldingham expects me to appear from time to time – I am less easy. In the great hall where we dine I am wretched.

It is not the food that discommodes me, nor, to be just to the company, the mannerliness with which I am received. I am my own enemy. My self, of which I am pleasantly forgetful at most times, becomes an obstacle to my happiness. I do not know how to present it, or how to efface it. See how I name it ‘it’, as though my self were not myself. My Lord and his friends talk to me amiably enough. But the contrast between the laborious politeness with which they treat me, and the quickness of their wit in bantering with each other is painfully evident.

As I write this, I feel myself to be quite a master of language, so why is it that, in conversation, words fall from my lips as ponderously as dung from a cow’s posterior? I will be the happier when the guests depart, and so, I fancy, may they be. Although the old portion of the house has not yet been invaded by the joiners and masons, the shouting emanating all day long from the wing under construction is an annoyance. And now that the work on the wall has begun, the park is encumbered with wagons hauling stone to every point on its periphery. The quarrymen set to at first light. We wake to the crack of stone falling away from the little cliff, and our days’ employment has as its accompaniment the clangour of iron pick on rock.

One congenial companion I have found. She is a young lady, not staying in the house, but frequently invited to enjoy whatever entertainment is in hand. She came to me boldly outdoors today.

I had been conferring with Mr Green, who is the chief executor of my wishes for the garden. He is, I consider, as worthy of the name of artist as any of the carvers and limners at work on the house – but because he is tongue-tied, those precious gentlemen are apt to treat him as a mere digger and delver. His own men show him the utmost respect.

Those goldfish that so put me out of countenance on my arrival have proved the seeds from which a delightful scheme has sprouted. The stony paving of the terrace is to be bisected by a canal, within whose inky water the darting slivers of pearl and orange and carnation will show as brilliant as the striped petals, set off by a lustrous black background, in the flower-paintings my Lord has brought home with him from Holland.

‘I hear, Mr Norris, you are rationalising Wychwood’s enchanted spring,’ said the lady.

‘You hear correctly, madam. Some small portion of its waters will trickle beneath the very ground on which you now stand. More will feed a fountain in the valley there, if Mr Rose and I can manage it.’

‘But have you appeased the genius loci, Mr Norris? You cannot afford to make enemies in fairyland.’

I was taken aback. I could not but wonder whether she teased. Were she any other young lady I would have been sure of it. But she is as simple in her manner as she is in her dress. Her name is Cecily Rivers.

*

‘I am glad you and my cousin are friends,’ Lord Woldingham said to me this morning as I spread out my plans for him. He is my elder by a decade, and inclined to mock me as though I were a callow boy. We were in the fantastically decorated chamber he calls his office. Looking-glasses, artfully placed, reflect each other there. When I raised my eyes I could not but see the image of the two of us, framed by their gilded fronds and curlicues, repeated to a wearisome infinitude. I, Norris the landskip-maker, in a dun-coloured coat. He, who will flutter in the scene I make for him, in velvet as subtly painted as a butterfly’s wing seen under a magnifying glass.

I do not much like to contemplate my own appearance. To see it multiplied put me out of humour. My Lord’s remark was trying, too. Often when it comes to time for inspecting the plans he finds some conversational diversion. I did not know whom he meant.

‘Your cousin, sir?’

‘My cousin, sir. You can scarcely pretend not to know her. Pacing the lawn with her half the afternoon. I have my eye on you, Norris.’

He made me uneasy. He loves to throw a man off his stride. In the tennis court, which abuts the stables, I have seen the way he will tattle on – this painter is new come to court and he must have him paint a portrait of his spaniel; this philosopher has a curious theory about the magnetism of planetary bodies – until his opponent lets his racket droop and then, oh then, my Lord is suddenly all swiftness and attention and shouting out ‘Tenez garde’ while his ball whizzes from wall to wall like a furious hornet and his competitor scampers stupidly after it.

I had no reason to fumble my words but yet I did so. ‘Mistress Rivers. Your cousin. I did not know of the relationship.’

‘Why no. Why would you, unless she chose to speak of it?’

‘She lives hereby?’

‘Hereby. For most of her life she lived here.’

‘Here?’

‘Yes. In this house. Cecily’s mother was not of the King’s party. She stayed and prospered under the Commonwealth while her brother, my father, wandered in exile.’

‘And now . . .’

‘And now the world has righted itself, and I am returned the heir, and my aunt is mad, and her husband is dead, and my cousin Cecily is delightful and though I do not think she can ever quite be friends with me, her usurper, she has made a playmate of you.’

‘Your aunt is . . .’

‘The quickness your mind shows when you are designing hanging gardens to rival Babylon’s, Mr Norris, is not matched by its functioning when applied to ordinary gossip. Yes. My aunt. Is mad. And lives at Wood Manor. Hereby, as you say. And Cecily, her sweet, sober daughter, comes back to the house where she grew up, in order to taste a little pleasure, and to divert her thoughts from the sadness of her mother’s plight.’

I must have looked aghast.

‘Oh, my dear Aunt Harriet is not wild-mad, not frenzied, not the kind of gibbering lunatic from whom a dutiful daughter needs protection. My aunt smiles, and babbles of green fields and is as grateful for a cup of chocolate as one of the papists, of whom she used so strictly to disapprove, might be for a dousing of holy water. I am her dear nevvie. She dotes on me. She forgets that I am her dispossessor.’

It is true that yesterday afternoon Miss Cecily and I walked and talked a considerable while on the lawns before the house. Had I known my Lord was watching us I might not have felt so much at ease.

*

It is Lord Woldingham’s fancy to enclose his park in a great ring of stone. Other potentates are content to impose their will on nature only in the immediate purlieus of their palaces. They make gardens where they may saunter, enjoying the air without fouling their shoes. But once one steps outside the garden fence one is, on most of England’s great estates, in territory where travellers may pass and animals are harassed by huntsmen, certainly, and slain for meat, but where they are free to range where they will.

Not so here at Wychwood. My task is to create an Eden encompassing the house, so that the garden will be only the innermost chamber of an enclosure so spacious that, for one living within it, the outside world, with its shocks and annoyances, will be but a memory. Other great gentlemen may have their flocks of sheep, their herds of deer, but, should they wish to control those creatures’ movements, a thorny hedge or palisade of wattle suffices. Lord Woldingham’s creatures will live confined within an impassable barricade. As for human visitors, they will come and go only through the four gates, over which the lodge-keepers will keep vigil.

Mr Rose took me today to view the first stretch of wall to have been constructed. He is justly proud of it. It rises higher than deer can leap, and is all made of new-quarried stone. When completed, it will extend for upward of five miles.

I said, ‘I wonder, are we making a second Paradise here, or a prison?’

‘Or a fortress,’ said Mr Rose. ‘Our King has had more cause than most monarchs to fear assassins. Lord Woldingham is courageous, but you will see how carefully he looks about him when he enters a room.’

‘His safety could be better preserved in a less extensive domain,’ I said.

‘He craves extension. He has spent years dangling around households in which he was a barely tolerated guest. There were times when he, with his great title and his claim on all these lands, had no door he could close against the unkindly curious, nor even a chair of his own to doze upon. He has been out, as a vagabond is out. Now, it seems, he chooses to be walled in.’

The wall is a prodigy. It will be monstrously expensive, but I am gratified to see what a handsome border it makes for the pastoral I am conjuring up.

*

This has been a happy day. It is never easy to foresee what will engage Lord Woldingham’s interest. I was as agreeably surprised by his sudden predilection for hydraulics as I had been saddened by his indifference to arboriculture. Having discovered it, I confess to having fostered his watery passion somewhat deviously, by playing upon his propensity for turning all endeavour into competitive games.

We were talking of the as-yet-imaginary lakes. I mentioned that the fall of the land just within the girdle of the projected wall was steep and long enough to allow the shaping of a fine cascade. At once he gave his crosspatch of a pug-dog a shove and dragged his chair up to the table. I swear he has never hitherto looked so carefully at my plans.

‘What are these pencilled undulations?’ he asked. I explained to him the significance of the contour lines.

‘So where they lie close together – that is where the ground is most sharply inclined?’ He was all enthusiasm. ‘So here it is a veritable cliff. Come, Norris. This you must show me.’

Half an hour later our horses were snorting and shuffling at the edge of the quagmire where the stream, having saturated the earthen escarpment in descending it, soaks into the low ground. My Lord and I, less careful of our boots than the dainty beasts were of their silken-tasselled fetlocks, were hopping from tussock to tussock. Goodyear and two of his men looked on grimly. If Lord Woldingham stumbled, it would be they who would be called upon to hoick him from the mud.

The hillside, I was explaining, would be transformed into a staircase for giants, each tremendous step lipped with stone so that the water fell clear, a descending sequence of silvery aquatic curtains.

‘And it will strike each step with great force, will it not?’

‘That will depend upon how tightly we constrain it. The narrower its passage, the more fiercely it will elbow its way through. This is a considerable height, my Lord. When the current finally thunders into the lake below it will send up a tremendous spray. Has your Lordship seen the fountain at Stancombe?’

Here is my cunning displayed. I knew perfectly well what would follow.

‘A fountain, Mr Norris! Beyond question, we must have a fountain. Not a tame dribbling thing spouting in a knot garden but a mighty column of quicksilver, dropping diamonds. I have not seen Stancombe, Norris. You forget how long I have been out. But if Huntingford has a magician capable of making water leap into the air – well then, I have you, my dear Norris, and Mr Rose, and I trust you to make it leap further.’

The Earl of Huntingford is another recently returned King’s man. Whatever he has – be it emerald, fig tree or fountain – my Lord, on hearing of it, wants one the same but bigger.

So now, of a sudden, I am his ‘dear’ Norris.

This fountain will, I foresee, cause me all manner of technical troubles, but the prospect of it may persuade my master to set apart sufficient funds to translate my sketches into living beauties. It is marvellous how little understanding the rich have of the cost of things.

‘My master,’ I wrote. How quickly, now the great levelling has been undone, we slip back into the habits of subservience.

*

This morning I walked out towards Wood Manor. I set my course as it were on a whim, but my excursion proved an illuminating one.

The road curves northward from the great house. I passed through a gateway that so far lacks its gate. Mr Rose has employed a team of smiths to realise his designs for it in wrought iron tipped with gold.

The parkland left behind, the road is flanked by paddocks where my Lord’s horses graze in good weather. It is pleasantly shaded here by a double row of limes. Their scent is as heady as the incense in a Roman church. The ground is sticky with their honeydew. The land falls away to one side, so that between the tree-trunks I could see sheep munching, and carts passing along the road wavering over the opposite hillside, and smoke rising from the village. It was the first time for several days, sequestered as I have been, that I had glimpsed such tokens of everyday life. I had not missed them, but I welcomed them like friends.

I became aware that I was followed by an old woman, the same I had now seen twice already. My neck prickled and I was hard put to it not to keep glancing around. I was glad when she overtook me and went hurriedly on down the road.

I had not intended to make this a morning for social calls, but it would have seemed strange, surely, to pass by Miss Cecily’s dwelling without paying my respects. I had told Lord Woldingham, before setting out, that I needed to acquaint myself thoroughly with the water-sources upon his estate. He seemed surprised that I might think he cared how I occupied myself. He was with his tailor, demanding a coat made of silk dyed exactly to match the depth and brilliance of the colour of a peacock’s neck. The poor man looked pinched around the mouth.

The house Lord Woldingham is creating will extend itself complacently upon the earth, its pillars serenely upright, its longer lines horizontal as the limbs of a man reclining upon a bed of flowers. Wood Manor, by contrast, is all peaks and sharp angles, as though striving for heaven. The house must be as old as the two venerable yew trees that frame its entranceway. As I passed between them I saw the sunlight flash. A curious egg-shaped window in the highest gable was swiftly closed. By the time I had arrived at the porch a serving-woman had the door ajar ready for me.

‘Is Miss Cecily at home?’ I asked.

‘You will find her out of doors, sir,’ she said, and led the way across a flagged hall too small for its immense fireplace. An arched doorway led directly onto the terrace. Cecily was there with an elder lady. Looking at the two of them, no one could have been in any doubt that this lady was her mother. The same grey eye. The same long teeth that give Cecily the look (I fear it is ungallant of me to entertain such a thought, but there it is) of an intelligent rodent. The same unusually small hands. Both pairs of which were engaged, as I stepped out to interrupt them, in the embroidery of a linen tablecloth or coverlet large enough to spread companionably across both pairs of knees, so it was as though mother and daughter sat upright together in a double bed. The mother, I noticed, was a gifted needlewoman. The flowers beneath her fingers were worked with extraordinary fineness. Cecily appeared to have been entrusted only with simpler tasks. Where her mother had already created garlands of buds and blown roses, she came along behind to colour in the leaves with silks in bronze and green.

I addressed my conversation to the matron.

‘Madam, I hope you will forgive the liberty I take in calling upon you uninvited. I am John Norris. I have had the pleasure of meeting Miss Cecily at Wychwood. I was walking this way and hoped it would not be inconvenient for you if I were to make myself known.’

She replied in equally formal vein. So I must be acquainted with her nephew. Any connection of his was welcome in her house. She hoped I enjoyed the improved weather. No questions asked. No information divulged. The maid brought us glasses of cordial while we played the conversational game as mildly and conventionally as a pair of elderly dogs, in whom lust was but a distant memory, sniffing absent-mindedly at each other’s hinder parts. But then she demonstrated that she could read my mind.