Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

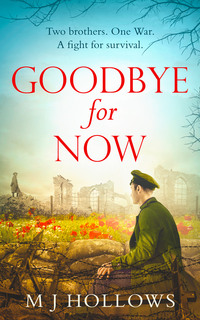

Kitabı oku: «Goodbye for Now», sayfa 2

Chapter 2

Joe let the door click shut behind him. He wanted so much to slam it, but in the end he backed down. What point would he make if he crashed about the place like some bull? He liked peace and the quiet protest of knowing wholeheartedly that he was right, no matter what anyone else said. It kept him going.

He had known what this morning’s breakfast conversation was going to hold, he had expected it. They had been edging ever closer to war, and every day he felt nearer to the time his father would ask him what he was going to do. This morning had been the breaking point.

He took a deep breath before opening the front door and walking out of the house. It was earlier than usual to leave for work, but he could always find something to do at the newspaper. It may be early for him, but the bakers on the end of the road were just finishing their morning cycle. The smell of warm bread was somehow comforting.

A horse and flatbed cart went past carrying large steel milk churns. Its wheels rattled on the cobbled road. Workmen were on their way to the factories, wearing heavy, protective clothing.

He forced a smile to them as he passed. Some of them were people he knew well, people he had grown up with, friends and relatives. They lived in such close confines that it was impossible not to know each other.

Already, people were running about and calling to each other, with a cheer that didn’t reach Joe. He was trying to push his father’s words out of his head, but he couldn’t forget how badly the conversation had gone. He had always known that he would refuse to join the army, but that wasn’t how he had wanted it to happen.

He turned the corner away from their little street and on to the main road. Upper Parliament Street glowed in the summer morning sunshine. The further he went the easier it might be to forget. Children in scruffy brown clothes with dirty white collars ran down the road, some waving Union flags and others pretending to attack their friends. The boys ran into a couple of regulars dressed in khaki coming out of a house. One of them smiled at a child and the other grabbed one and put him on his shoulders before joining in the chase of the other boys, laughing.

It was a fine morning and the walk would do him good. The air was light and clear, feeling good in his lungs as he walked. A motorcar went past, its engine chugging out fumes, easily overtaking the lumbering horse carts. The roads rose up as they moved away from the city, giving a view of the River Mersey, houses built onto the hills to the south of the city. The Mersey reflected sunlight as the tide came in, a faint mist beginning to grow.

In the distance he could just about make out the recently opened Liver Building, its two domes each housing a stylised Liver Bird. He remembered the opening that the newspaper staff had been invited to. At the time one of the workers had told him a story about the two birds on top of the building. ‘The female bird, ya see, is looking out to sea for the returning ships, right? And the male bird is looking into the city to see, to see if the pubs are still open.’ The man’s laugh had been deep and booming, and the memory made Joe smile.

He ended up on Wood Street, one of the small roads that intersected the city centre, housing the many offices and shops. The Liverpool Daily Post building was one of the largest on the street, rising above the horizon in an edifice of brick and glass. The other buildings along the road had grown up to it, but none matched. At this time of the morning the low sun was hidden behind the building, which cast a shadow on the road. The Daily Post sign looked down on all those in the street, ready to proclaim its news.

Joe walked in and nodded to the clerk at the front desk. Stephen nodded back and carried on with whatever he was reading. It was a ritual, but today Stephen paused, putting his magazine down, and looked on the verge of saying something. Joe climbed up the wrought iron stairs that turned back on themselves, avoiding the conversation, and into the main offices on the first floor.

He hooked his hat on the hat stand that always stood by the door. The large post room had rows of metal desks across the middle, machine-built in a large quantity by the same smith that had built the press. It always made him proud to see the amount of work they put into the newspaper, and proud to be involved.

The journalists and copywriters hadn’t all arrived yet. Those that were already in the building were looking through the other morning papers, the Manchester Guardian, and The Times all the way up from London on the morning train. They were too busy pretending to work and talking amongst themselves. They didn’t look up as he sat down at his desk.

Two other workers came into the room at that moment and called to the ones that had already arrived whilst putting their hats and coats on the stand at the doorway.

‘Good morning!’ they both shouted, almost in harmony.

‘I guess you’ve heard the news then, Frank?’ Charlie called back.

‘Stop shouting, Ed will hear you, and you know what he’s like about noise,’ Frank said as he walked past the desk, giving Joe a quick wink.

He could still hear the conversation once they had passed; despite telling each other to be quiet they were talking in loud voices as they sat together, any pretence of work forgotten. The customary snap of a match signalled that they were smoking, before the smoke filled the room.

‘…Not before time,’ one said in the kind of voice that suggested he thought he knew everything there was to know about everything. ‘Them Austro-Hungarians were just spoiling for a fight. Can’t have ’em taking over Europe.’

Even though Joe couldn’t see the speaker from where he was, he knew Charlie would be looking smug with himself, whilst trying to pretend he wasn’t. He could hear it in his overconfident voice.

‘Ahh whaddya know, Charlie Mason? You’d make an awful soldier. Look at you.’

‘What rot, I’d be great. Just you wait and see.’

There was an almighty laugh as the other men had fun at Charlie’s expense.

The boisterous camaraderie of the office and the type room was not for Joe. Idly, he pulled a sheaf of papers towards him and took out a fountain pen from its slot in the desk. He couldn’t concentrate and instead sat, holding the pen, and looking out over the office, staring blankly at the opposite wall.

‘Abbott.’

The hard, croaky voice of Edward Harlow made Joe look up at the slightly fat man, whose bald head shined in the electric lights of the office. The editor let a puff of smoke drift around Joe as he stood above him. He was always smoking; it was as if he had decided that it was something that an editor should do. As a result, it made his voice somewhat distinctive, along with the heavy breathing that accompanied his walking. It sounded like he was trying to talk through the reed of a woodwind instrument. It was a sound that the other men in the office had found especially useful when trying to avoid working. They always knew when he was coming, even if they didn’t smell his cigar first.

‘Good morning, Mr Harlow. How do you do?’ Joe made the pleasantry without wanting an answer. It was just what one did.

‘I take it you’ve heard the news then? You can hardly avoid it round here, what with all the noise and excitement.’ With that he looked over at the other men and then at the still empty desks of the office. They were once again pretending to read the newspapers. Research, they would call it, if pressed.

Joe nodded, not knowing what to say. The news had been coming, but he wasn’t a war reporter, so it wasn’t his responsibility.

‘I’m sorry, Abbott,’ Mr Harlow coughed. ‘The news came through last night, almost immediately after you left. I had to give the article an edit myself when it came through. Priority you see, when it comes to declarations of war. We had to get it ready for this morning, see. The typesetters were about ready to go. “You know how much it costs to stop once we’ve started,” they said, but I had to. If it didn’t go out this morning, the owner would have my neck.’ The apology was unnecessary, given Joe’s position, but characteristic of the man. He wanted to be every one’s best friend.

‘But forget that. It’s happened now, and no doubt we’ll pay the price for it sooner or later.’ Mr Harlow wagged a finger at Joe as if telling him off then paused, thinking about his own words and taking a puff of his cigar.

‘I’ve got this here for you. Something to work on, and I need it pretty sharpish. Forget that other rubbish.’

He pushed the piece of paper under Joe’s nose. ‘Enlist to-day. The Germans pillage Belgium!’ the headline read. If that was how the headline started, then he daren’t read the rest.

Why was Mr Harlow giving him this piece to edit? Could it be because he felt bad about working without him last night? Joe doubted that. It made a change from his usual job of looking through the local pieces for any mistakes or spelling errors, but it wasn’t what he wanted to be involved in. It wasn’t like he had shouted it from the rooftops, but surely Mr Harlow must know of his opinions.

‘When you’re done with that and it goes out, the office will empty.’ Mr Harlow sighed. ‘Seems that some of the lads have already deserted us. That or they’re just bloody well late!’

So that explained the empty desks. He only swore when he was angry and he was giving Joe this piece because there was no one else around to do it. So much for taking his mind off the pressure of the war, instead he had to edit this abhorrent article. Albert Barnes had written it to encourage other young men like him to sign up, whatever the cost.

‘I’m not sure this is my thing, Mr Harlow,’ he said with hesitation. When he looked up, the editor had already gone, the waft of cigar smoke following in his wake.

He looked back at the article, pushing aside his other work. The headline was no worse than the rest. Crammed into the tiny article were all the atrocities that the German army had already engaged in during their short time marching into Belgium. He had no idea where the information had come from; he knew for sure that Barnes had never left the city, he wasn’t the kind of man to go off in search of a story. How could he possibly know that any of this was true?

Joe couldn’t bring himself to endorse it.

Allegedly, men were already leaving their jobs to sign up for the war they had been anticipating for months. To see off the invading Germans and send them home with their tails between their legs. They didn’t need the help of this propaganda and supposition to encourage them, many had already made that decision on their own.

‘Wondering what it’d be like to be in uniform, Joe lad?’

Frank Gallagher liked the sound of his own voice and, seeing as he occupied the next desk, Joe was often on the receiving end of it. Joe hadn’t noticed him come over, but now Frank was sat side-saddle on his chair and smirking. His face was pockmarked with the remnant signs of acne.

‘I fancy me in a bit of khaki, like. Reckon the girls will lap it up.’

He smiled stupidly, enjoying himself, and Joe reluctantly smiled back. He had to admit that even though Gallagher could be annoying at times, he did have a certain charm. He made you want to laugh and join in with his japes.

Joe didn’t say anything and just shook his head in a playful manner. For once he could imagine why people might sign up, with the honest camaraderie of people like Gallagher, but it was still war.

‘Come on, lad. Ya never know, you might find yourself a sweet lass too.’ With that he laughed and punched Joe lightly on the shoulder. ‘But then we’d have to drag you away from your work.’

What would it be like once the war started proper, if everyone went off to fight? Would it be him and Mr Harlow left all on their own to run the paper? How on earth was the country going to cope? He didn’t like the thought, and once again tried to push thoughts of the war out of his mind and press on with work.

‘Is that where Barnes and Swanley are, Frank?’ He nodded over at their empty desks.

‘What? Them two? Lost if I know where they are. They live by their own rules them two. Even the territorials would give them a wide berth.’ He scoffed and shook his head. ‘They’d look rubbish in a uniform. And they already get all the girls anyway. Leave some for old Frank, that’s what I say.’

Joe laughed despite himself.

‘I just saw Mr Harlow, and he gave me one of Barnes’s articles.’ He held up the sheet of paper he was supposed to edit.

‘Aye, I saw him on the way in too, muttering to himself. He didn’t even notice me. Thought it were best to leave him to it.’

‘I don’t suppose you could take it off my hands, Frank? I’m a bit busy you see.’ He pulled the pile of local articles and adverts closer and smiled at Gallagher. There was no point in telling Frank that he didn’t want to work on it himself. He wouldn’t understand.

‘Oh no! You’re not getting me in trouble that easily.’ The big smile lit up his face. ‘I’ve only got a few more days’ work to get through before I can get out of here. Last thing I want is old Ed Harlow coming down on me for doing your work for you. He’s given that to you. I’ve got other stuff to do.’ He shuffled a pile of papers on his own desk. ‘Gotta make this lot respectable. Half them journalists can’t write for toffee. I’d swear on me old gran that they make up some of this stuff. Some of these words I ain’t even heard before.’

Joe didn’t doubt it; Frank was a nice guy, but he wasn’t the most intelligent. Joe suspected the questioned words were in fact real words, but he was better off leaving Frank to it – he had his style, which was popular with the readers.

‘You’ll have to find someone else to pass the boring ones to.’

‘This one isn’t exactly boring, Frank.’

‘I know, just glancing at it has already made me want to sign up.’ He gave Joe a thump on the arm in jest, and Joe resisted to urge to say ‘ow’. ‘But, well, that’s not the point. I’ve already decided I’m going. Perhaps reading what Fritz is up to might give you that kick you need to join in the fun too.’

‘But, how do we know any of this is true, Frank?’

‘What do you mean, true? Of course it’s true. We’re newspaper men, if we don’t know what true is then who does? True…’ He shook his head.

‘But all these horrible things, I can’t believe that they would do that. We have no proof, other than hearsay.’

‘Of course they’re up to no good. They started a war, Joe. That’s not a particularly friendly thing to do now is it?’

‘I suppose not.’ He put the sheet down. ‘Really though, we should be staying neutral, Frank. It’s not our war.’

‘Don’t be stupid, Joe. That’s not like you. Of course it’s our war.’ For once Frank was serious, his usually bright eyes surveyed Joe in a way he hadn’t seen before.

‘Them Germans want Europe for themselves. All this stuff that’s happened leading up to this was just rot, designed as an excuse. They’ve been spoiling for a war for ages now, and it’s been left to us to stop them. We’ll see that we do. Our Tommies are the only ones that’ll stand up to ’em.’

It was no use. Frank was just like all the rest: well meaning, but misguided. Joe wouldn’t get anywhere by trying to make him see reason, and to question what he was told. Everyone was determined that the only way to stop the – alleged – despicable acts of the Germans was to counter them with yet more despicable acts. He would have to try another tactic.

With that thought, he pulled out the copy of the Labour Leader from the top drawer of his desk and flicked through the pages for the article he sought. With a pen he began crossing out lines and rewriting them with added argument, inspired by the words of Fenner Brockway and the other socialist writers. It wasn’t much, he didn’t know how many people would read the article now that he had crossed out the headline, but he could dissuade some men from fighting. He hoped he could make a difference. He had to do something.

Chapter 3

‘There’s a ship mooring at the Duke’s dock,’ someone shouted. The men picked up kit, off to find some maintenance work, but George had none. He got a running head start on them, with Tom by his side. They pounded along the cobbled streets, the soles of their boots clicking on the surface with each footfall. At first his boots had rubbed his feet to tatters, but now they were so worn in that it felt like he was running barefoot. Sweat caused by the glaring sun dripped down from his temples and ran round the curve of his neck, under his clothes. It was almost unbearable, but he kept running, otherwise he wouldn’t get there in time.

War had almost been forgotten in the last few days, as work had taken over. They crossed Gower Street and ducked around a carriage, the coachman swearing at them, before running into the Duke’s dock underneath the brick arch of the dock house. The dock smelled strongly of salt water and that ever present stench of fish that got into the nostrils and never left. There was a ship mooring at the dock. George craned his neck to see around the men in front of him. It was a small ship. Its sails were furled and it was being guided in by a small motor. Rope was already being pulled over one of the mooring posts. A man assisting in the mooring saw them coming and blocked their way. ‘Easy now,’ he said, raising the palms of his hands. The men almost didn’t stop. ‘Easy,’ he said again, louder.

This time the men stopped in front of the dock master. ‘I need ten able-bodied men to unload this cargo,’ he said. ‘No more.’ There was a collective groan from the group, about fifty, most of them in tatty clothes. ‘She also needs some caulking, if you can do it.’

A man towards the back of the group with a heavy tin toolbox put a hand up and pushed forward past the dock master. The master started assigning men tasks. ‘You, you, and you,’ he said to three men a couple of rows in front of George. The rest of the men jostled to get noticed, but the master just scowled, picked the rest of the men from elsewhere.

Tom cursed. ‘I thought we had got lucky there, George,’ he said with a shake of his head.

‘Back to the custom house?’ George said. ‘We can look in on the arrivals there.’ Work was scarce on the dock, and down to luck.

The dock master came back over to the group. ‘There’s a big haul coming in, lads. If you’re quick.’ There were calls from the crowd, asking where.

‘…King’s dock’ were the only words George heard, as he dragged Tom after him. The two of them spent most of their days running from one place to another. He didn’t mind the running, but it was the sweat that he couldn’t cope with. In winter it was fine, the running kept you warm, but in the summer it was unbearable. He tried to wear as few layers as possible, but the clothes were for protection. If a piece of cargo slipped it could cut a hole, he’d seen it happen. The boys crossed to the King’s dock. It was a good distance to get to King’s dock. Some part of George suspected that it wouldn’t be worth the effort, but they had to try. Their families depended on the income. Even if it was only a few pence.

As they turned the corner the expanse opened up to a much greater view. King’s dock was much larger than Duke’s. Here the buildings were spaced back, allowing the cargo to be offloaded and moved to better locations. There was indeed a ship entering the dock, larger than the last. It was crawling into the moorings, carefully using the rudder to make sure that it didn’t hit the dockside. It let off its horn, blaring across the dock, almost deafening, and some of the men following George and Tom cheered, feeling their luck was in.

This time the dock master agitatedly waved them into a queue at the side of the dock without saying anything. If the men pushed their luck they would be dismissed without a chance to earn any pay. So they waited, eager, but cautious.

He started assigning them off into queues, and only a few minutes later George and Tom were busy rolling heavy wooden barrels of brandy away from the dockside to a horse-cart that would take them away to a holding area. It took two men to roll each barrel, one guiding while the other put all their weight behind it and gave it a great shove. George and Tom had plenty of experience and idly chatted amongst themselves while they worked. They stopped for a moment to catch their breath, having just loaded the last barrel that would fit onto the cart, rolling it up the wooden chocks that formed a slope to the hold. The coachman put up the tail board with help from Tom to seal the other side.

‘You were right,’ Tom said, holding up a paper he had taken off a bench. The headline indicated that the war was in the morning paper again. It had been all that people had talked about since the ultimatum had expired.

George wondered what Tom was talking about. Staring at him, he urged him to continue.

‘About them wanting more troops,’ he said. ‘You were talking about it the other day, remember? It says right here that Lord Kitchener has asked for another hundred thousand men.’

There was a loud crack, accompanied by the snap of breaking wood, which seemed to drag the sound out from its initial burst.

He turned to see a shape rushing towards them. He called out to Tom but it was too late. He just had time to reach for Tom and push him out of the way before an escaped barrel knocked into his back with force.

Tom fell to the ground with a cry as the metal-clad wood knocked into him. It carried on rolling past, and George was just about able to get out of its way, before it crashed against the brick wall of the dock house and burst open, spilling its contents all over the cobbles.

The coachman rushed to the back of his cart. The back plank had come undone, allowing the barrel to slip off the cart and run free. With the help of a few others, he managed to stop any more barrels falling off the cart and lashed them to the decking with some spare rope.

George ran over to Tom, sprawled on the cobble floor. Tom had been hit in the back and was lying face down. He feared the worst, but Tom just groaned and tried to roll over.

‘Don’t move, Tom. I’ll get help.’

Tom just smiled back at George as he always did and he pushed George away as he tried to check him for wounds.

‘Ah, don’t worry, George.’ He groaned as he sat up and put a hand to his back. ‘I’m all right, I’m all right.’

He finally accepted help but shook his head. George helped him up with a hand under his armpit and then dusted him down. There was a bit of blood on his forehead, but nothing on the rest of his body except for a bruise that would blacken over the next few days. George wet his handkerchief and handed it to Tom as he motioned for him to wipe his forehead. Seeing that George was taking care of Tom, the coachman got back up on his cart and led the horse away – any delay would cost him money.

‘Are you sure you’re all right?’ George asked.

‘Yeah. It was lucky you shouted,’ Tom said as he wiped the crusting blood from his forehead and winced at the pain. ‘I would have been stood stock still if you hadn’t. That shove helped too. I avoided most of the barrel.’ He stretched his back. ‘Still gave me a bloody great thump though. I’ll feel that one in the morning, no doubt. Let’s see what else they need us to do.’

He turned to walk away, but George grabbed him by the arm.

‘We should call it a day. You’ve had a nasty bump. That could be a head injury too,’ he said, gesturing towards Tom’s forehead again.

Tom shook his head and tried to hide another wince. The smile was back again. ‘There’s nothing wrong with my head,’ he said. ‘If we’re quitting work, do you think we should volunteer?’

George let go of his arm. ‘Come on, let’s go home. I’ve had enough for one day.’

‘I’m serious.’

George wiped the smile from his face, knowing it was doing him no favours in this situation.

‘I’ve been thinking about it a lot. No matter what else I do, I keep coming back to the same thought.’

George tried to show compassion and lighten the mood. ‘I know, you haven’t shut up about it since the other day.’

At that moment the dock master ran over to them and started shouting. He was an overweight man, his belly threatening to escape his waistcoat, and his hair was balding, leaving a sweaty pate of pink flesh.

‘What the hell is going on here?’ he shouted when he had got his breath back from the run. A frown crossed his face.

‘You.’ He pointed at Tom, who was still stretching his back, visibly uncomfortable at the pain. ‘What did you do? Why are you slacking?’

Tom shrugged. ‘I’m not,’ he said. ‘The cart’s full, and we’re going back for more.’

The dock master wasn’t appeased.

‘Don’t lie to me. I heard a commotion, what’s going on? If you’ve caused any damage…’

It was at that moment that he noticed the destroyed brandy barrel. It was a wonder he hadn’t seen it sooner, the stench of brandy was strong in George’s nostrils. The dock master’s eyes widened as he took in the broken wood and the precious cargo draining away through the cobbles.

‘You damaged the cargo,’ he said through gritted teeth.

‘What?’

The dock master grabbed Tom by the collar, even though Tom was a good foot taller than him.

‘Do you have any idea how much that barrel was worth? More money than you’ll ever have.’

‘What?’ Tom said again, unsure. ‘I didn’t do anything. You’re mad.’

‘Damn right I’m mad. How are you going to pay for that?’

George moved to help Tom, but couldn’t see how without angering the dock master further. Instead he tried to calm him down.

‘Tom didn’t do anything, sir. The tail board on the cart broke and the barrel rolled off. If you ask the coachman he will vouch for us.’ The coachman wouldn’t be back for a while, but at least it might buy them some time.

The dock master turned to George, still holding Tom by the collar.

‘Who asked you? As far as I know you’re just as much to blame as this idiot is.’

Tom used that moment to break free of the dock master’s grasp. With a lurch, he pushed the smaller man away with both hands. He moved backwards and tripped over a cobble, but thanks to his low centre of gravity, managed not to fall.

‘I didn’t break the barrel, sir. In fact, it almost broke me.’ As a gesture of goodwill, Tom checked the man over to make sure he wasn’t hurt. ‘Now, if you don’t mind, my friend and I would like to get back to work. There are plenty more barrels like that that need moving and if that doesn’t get done, then I guess you’ll lose even more money.’

The dock master trembled, in shock from Tom’s shove, then nodded.

‘Fine. I’ll chase that coachman for this. But if either of you lads does anything like this again, if you put one finger where it shouldn’t be, then I will make sure that you never work anywhere on these docks again.’

He walked away, his pace slightly quicker than a walk like someone trying to escape a confrontation with an enemy without drawing attention to himself.

‘Now get back to work,’ he called over his shoulder, as if it was his idea and not Tom’s.

‘That was close,’ Tom said, grabbing George by the arm and leading him away. ‘Come on, let’s get this over and done with.’

They went back to work, but before long the conversation had returned to the war.

‘Well now, I think they’ll take me,’ Tom said out of the blue, and George rolled his eyes at him, even though Tom wasn’t paying attention. ‘They need more men, they’ll take anyone that can hold a rifle at the moment. Besides, what have I got to lose? I’ve not got much here except my old mum. It’s gotta be better than this. Anything is better than this.’ He stopped and gestured at the barrel he had been rolling towards the new cart. The previous coachman hadn’t come back.

He stretched his back and groaned at the pain. Injuries were common around the dock, and Tom was lucky it hadn’t been worse. Every week one or more of the lads working on the dock ended up in a ward, or sometimes worse: a mortuary.

George grunted. It wasn’t so much that he agreed with Tom – he resented the fact that he had only thought about his mother and not his friends – but Tom had that way of getting you to see his point of view.

George thought about Tom leaving, and about working on the dock alone. It didn’t appeal to him. They made a good team.

‘If you go, Tom, I can’t go with you,’ he said.

‘Sure you can, if that’s what you want. Why not?’

‘For a start, I’m not old enough. You have to be nineteen before they’ll send you abroad, eighteen if you just want to stay at home doing something boring.’

He saw the dock master prowling along the path and gestured to Tom to resume their work. ‘At least, that’s what my dad always told us. He’s been counting down the days.’

‘Ah, come on now, George.’ Tom shook his head as he always did when he thought George was being unreasonable. ‘If you want to sign up, they’ll take you. By the sounds of it they’ll take anyone. That old dock master over there might even be in khaki soon. You’ll see.’

They both laughed at the thought. It was a welcome relief to the melancholy that had settled on them during the day, and finally Tom was smiling again.

‘You don’t want to wait till eighteen or nineteen to go down the recruitment office. You’ll be sat twiddling your thumbs, hearing about all the heroic deeds we’ve been up to out there. It’ll all be over by the time your eighteenth birthday comes, then what’ll you do? Start another war, just so you can fight in it?’

He was poking fun at George, but the smile was so warm it was difficult not to get dragged along in his wake.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.