Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

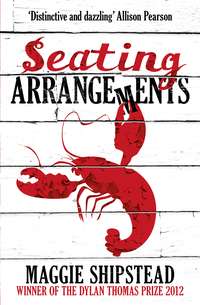

Kitabı oku: «Seating Arrangements», sayfa 2

He went around stamping cheeks with his businesslike kisses: first Daphne and then Biddy’s sister Celeste where she stood beside the refrigerator fishing an olive out of a jar with her index finger. Agatha and the other bridesmaids were lolling against the counter, and he kissed each of them, saying, “Agatha, hello again, Piper, Dominique.”

“How was the trip?” asked Biddy.

“Easy. I got an early start. The crossing was smooth.”

Celeste thrust a half-filled tumbler into his hand and clinked it with her own. Three olives drifted around the bottom. “You don’t have any martini glasses,” she said. “Other than that, everything has been fabulous.”

Setting the glass on a stack of magazines, he said, “Is the sun over the yardarm already?” He seldom drank hard liquor anymore, especially not in the middle of the day, but if he reminded Celeste of this, she would want to know for the umpteenth time why not, and he was in no mood to explain that it had to do with his headaches and not at all with any judgment of those who daily embalmed their innards from the moment the sun inched past its apex to the hour when their feet tipped them onto whatever couch or bed was handiest.

“Depends on where you keep your yardarm,” she said. Her smile was localized to her lips and their immediate region. Biddy had explained that Celeste had gotten carried away with wrinkle injections, but the effect was still eerie.

Winn frowned and turned to the bridesmaids. “Having a good time, girls?”

“Yes,” came the chorus from the bridesmaids, who had settled with Daphne in a languid clump against the sink. Like Daphne, Agatha and Piper were blond and short. Dominique was tall and dark, a menhir looming over them. She was the child of two Coptic doctors from Cairo and had spent most of her breaks from Deerfield with the Van Meters. Her face was symmetrical but severe, a smooth half dome of forehead descending to steeply arched eyebrows, a nose with a bump in its middle, and a wide mouth that drooped slightly at the corners in an expression of not unattractive mournfulness. Muscle left over from her days as a swimmer armored her shoulders and back. Her hair, which was not quite crimped and African but also not smooth in the way of some Arabs’, was cut very short. He hadn’t seen her for a few years. After college in Michigan she had flown off to Europe (France? Belgium?) to become a chef. He liked Dominique; he respected her physical strength and her skill with food, but he had never understood her friendship with Daphne, who took no interest in sports or cooking and who seemed diaphanous and flighty beside her.

Dominique pointed one long finger out the window. “Your garden is looking a little peaky,” she said.

“So Biddy told me. I haven’t gone out to take a look at it yet.”

“Were you having problems with the deer?”

“Terrible. They’re glorified goats, those things. But Biddy doesn’t think they’re the culprit this time.”

“Yeah, I didn’t see much nibbling, except around the edges. And I looked for aphid holes and that sort of thing but didn’t see enough to explain why it all looks so sad. Maybe the soil is too acidic.”

“Could be.”

“Did you do the planting?”

“The first time, eight or nine years ago, but a local couple does the basic caretaking when we’re not here. Maybe they tried something different. I hope if they wanted to experiment they wouldn’t do it in my garden.”

Dominique nodded and looked away as though concealing disdain for people who did not tend their own vegetable gardens.

“I’m so psyched for the wedding,” Piper announced out of the blue and in a high chirp, which was her way. She and Daphne had met at Princeton, and Winn knew her less well than the others. Always in motion, propelled along by a brittle, birdlike pep, she seemed a tireless font of chipper enthusiasm. She was pale as bone and dwelt beneath a voluminous haystack of white blond hair, her glacial eyes and red-lipsticked lips adrift in all the whiteness like a face drawn by a child. Her eyebrows were barely discernible, her nose small and sharp. Some men found her powerfully attractive, Winn knew, but she left him cold. Her looks were ethereal and a little strange, but Agatha’s were concrete, radiant, tactile; her limbs could almost be felt just by looking at them. Daphne fell somewhere in the middle. They were three shades of woman arrayed side by side like the bewildering, smiling boxes of hair dye in the supermarket.

“It’s beautiful here,” Agatha said, letting her head fall onto Piper’s shoulder. A male friend of Daphne’s had, years ago, in a moment of drunken gossip, implied that Agatha was a closeted prude—There’s no engine, he’d said. You hit the gas and nothing happens—but Winn had trouble believing something so disappointing could be true.

“Thanks for bringing my dress, Daddy,” Daphne said.

“Yes,” he said to Agatha. “Waskeke is the way the world should be.” He was staring at her too intently and looked away, at Biddy, who was rummaging through the grocery bags. With a grunt, Daphne pushed off from the sink, waddled across the kitchen, and plopped into a Windsor chair behind Winn. “Daphne,” he said, turning, “are you feeling all right?”

“I feel fine,” she said.

“Why did you make that noise?”

“Because I’m seven months pregnant, Daddy.”

He asked for and received a full briefing on the status of the weekend. Where was Greyson? At the hotel with his groomsmen, Daphne said. His parents? They would be arriving around five. The head count for that night’s party, a dinner Winn would be preparing, was seventeen. The get-together would be a casual thing, with lobsters, a chance for everyone to enjoy the island before they had to get serious about matrimony, a sort of pre-rehearsal-dinner dinner. Had Biddy confirmed the lobsters? She had.

Winn nodded. “All right,” he said. “Well, then good.”

“By the way,” Daphne said, “Mr. Duff is allergic to shellfish.”

Winn fixed her with a look. “Why didn’t you tell me sooner?”

“It’s no big deal. Just buy a tuna steak, too.”

“Are you going to call him Mr. Duff after you’re married?” asked Celeste.

“I have a hard time addressing him as Dicky,” said Daphne gravely. “He says to call him Dad, but most of the time I don’t call him anything.”

Biddy said, “Everyone calls him Dicky. It’s his name. He won’t think it’s odd for you to call him by his name. You’re being ridiculous.”

“Re-dicky-ulous,” said Dominique, and the women laughed.

“Where’s Livia?” Winn asked, even though he knew.

“Around here somewhere,” said Daphne. “Hating me. You know, I really think her dress is pretty. I really do. I wanted to set her off from the other bridesmaids, which is a nice thing, isn’t it? She’s just being contrary. It’s a green dress. That’s all. She says it’s the exact shade of envy and everyone already thinks she’s jealous even though she’s not, but it’s not the color of envy. It’s more of a viridian.”

“Too late to change it,” said Biddy.

The moment of welcome faded into a lull. The staring half circle of female faces made Winn uneasy. With a loud, contented sigh, he turned to look out the window. Daphne held her hands out to Dominique and was heaved to her feet. “Ladies,” she said, beckoning to her bridesmaids. They wandered off, their voices drifting through the house like the calls of distant birds.

“Nice trip?” Celeste asked, having lost track of the earlier part of the conversation.

“Couldn’t have been smoother,” he said.

“You must have gotten up at the crack of dawn.”

“Just before.”

“Drink up there, Winnifred.” She picked up his glass and handed it to him again with a wink. “You deserve it.”

“If you insist.” He touched his lips to the liquid. Gin.

The house was L shaped, with a planked deck filling the crook and extending out over the grass. Through the kitchen’s French doors, Winn saw Livia walk up the lawn and onto the deck. She wore an old pair of gray shorts, and her legs were thinner than he had ever seen them. When she came through the doors and into the kitchen, a push of salt air came with her.

“Oh, Dad,” she said. “Hi.”

She made no move to embrace or kiss him. In the hammock, she had appeared sepulchral and blue, but that must have been a trick of the shade because she looked fine now, a bit pale but fine. She turned away, chewing the side of her thumbnail.

“Hi, roomie,” Celeste said.

“You two are bunking together?” Winn said. Biddy must have sprung the arrangement on Livia, otherwise he would have already gotten an earful.

“Yes,” said Livia in a neutral voice, inspecting her hand. The nails were bitten to nothing, and the flesh around them was torn and raw.

Celeste jiggled her glass enticingly. “Can I get you a drink?”

“No, thanks.”

“Moral support for Daphne?” Celeste asked. “Poor thing not having a drink at her own wedding. I don’t know what I would have done without a drink or two during my weddings.”

“Let alone your marriages,” Biddy said.

“Only you,” Celeste said, swatting Biddy’s flat backside, “could say to that to me.”

“Daphne can have a glass of champagne,” Livia said. “She’s seven months. It’s fine.”

Celeste sipped. “Is it? Shows what I know.”

“Maybe I will have a drink,” Livia said. “I’ll get it myself.”

“How is Cooper?” Winn asked Celeste. “Still in the picture?” He reached out to touch Livia’s hair as she moved away.

“He’s fine. He’s sailing in the Seychelles. He wanted to come but he couldn’t.”

Livia took a bottle of wine from the refrigerator and picked at the foil. “Do you think he’ll be number five?”

“I’m getting out of the marriage business.” Celeste raised her glass as though someone had made a toast. “Though I’ll admit all this is making me sentimental. Nothing beats being a bride. Oh well. Days gone by. I’ll have to live vicariously through my nieces.”

Livia threw the foil into the garbage. “Don’t look at me.”

“Oh, sweetheart, it was his loss. There are so many fish in the sea. You’re only nineteen.”

“I’m twenty-one.”

“You are? Well, then, you’re an old maid.”

Livia put a corkscrew to the bottle and twisted it. Winn watched the curl of silver disappear. Her fingers wrapped so tightly around the bottle that her bones stood out under her skin. Winn wanted to tell her she didn’t need to squeeze so hard, wringing the bottle’s neck like she was. He remembered once watching her shatter an ice cream cone in her hand, crying out in surprise at the cold shards of waffle. “I forgot I was holding it,” she had said. “I was thinking of something else.” Why Livia always had to be so forceful, straining when she didn’t need to, was beyond him, but he held his tongue. She clamped the bottle between her knees and pulled until it exclaimed over the loss of its cork.

Two · The Water Bearer

Before he became a father, Winn had assumed he would have sons. He had expected Daphne to be a boy, had lain with his ear against Biddy’s pregnant belly and heard male voices echoing down from future lacrosse games and ski trips. He saw a small blue blazer with brass buttons, short hair combed away from a straight part, himself teaching a boy to tie a necktie. He would drive his son to Harvard when the time came and help him carry his bags through the Yard, would greet his son’s roommates and their fathers with hearty handshakes. His son would join the Ophidian Club, and Winn would attend the initiation dinner and drink with the boy who would live his life over again, affirming its correctness at every juncture.

When the screaming ham hock the doctor pulled from between Biddy’s legs turned out to be unmistakably female, all crevices and puffiness, he felt a deep and essential surprise, not only that the child brewing in his wife those nine months was a girl but that he, Winn, possessed the seeds of a feminine anything. Inside the tangled pipes of his testicular factory there existed, beyond all reason, women. Watching Biddy and Daphne nestle together in the hospital bed, he realized he had been mistaken to think that pregnancy and birth had something to do with him. He had imagined that by impregnating this woman he had ensured she would deliver a son who would go forth and someday impregnate another woman who would, in turn, have a son, and so on and so forth down the Van Meter line into the misty future. But now, instead, there was this girl-child who would grow breasts and take another man’s name and sprout new branches on an unknown family tree and do all sorts of traitorous things a son would not do. The shifting and swelling of Biddy’s boyish body into a collection of spheroids, the quiet communion she lavished on her belly, her new status with her sisters and her covey of friends—all this should have told him he was standing at the threshold of a club that would not have him. Even though women held out their arms and exclaimed, “You’re going to be a faaa-ther!” he suspected they had seen him all along for what he was: the adjunct, the contributor of additional reporting, the lame duck about to be displaced from the center of his wife’s affections. The surprise should not have been that he had a daughter but that any boys were ever born at all.

When, five years later, Biddy announced she was pregnant for the second time, Winn assumed from the first that the baby would be a girl. The deck was stacked; the game was rigged. Daphne was so staunchly female that the possibility of his and Biddy’s genes being put back in the tumbler and coming out a boy seemed too small to bother with. Biddy gave him the news in bed in the morning, and he kissed her once, hard, and said, “Well!” before going downstairs to sit behind the Journal and think about a vasectomy. He was at the kitchen table, staring sightlessly at the pages when he heard the rustling, tinkling sound that announced Daphne. She slid into a chair and sat eating red grapes out of a plastic bag. She wore a piece of crenellated, bejeweled plastic in her hair, and a cloud of pink gauze stood up where her skirt bent against the back of the chair.

“Good morning, Daphne. Going to dance class today?”

“No. That’s on Wednesday.”

“Isn’t that a dance skirt you’re wearing?”

“My tutu? I just threw this on.”

Winn stared at her. She looked back at him and fingered one of the strands of plastic beads that garlanded her neck. Somehow in her infancy she had absorbed a set of phrases and mannerisms that Biddy called breezy and Winn called absurd but that, in any event, had her swanning through preschool like an aging socialite. They left her once with Biddy’s eldest sister, Tabitha, and went to Turks and Caicos for a week, hoping Tabitha’s son Dryden would get her to dirty her knees a little. Instead, they returned to find Dryden draped in baubles and Daphne arranging clips in his hair.

“Dryden,” Biddy said, “you look awfully dressed up for this time of day.”

The boy released a sigh of weary sophistication. He fluttered his blue-dusted eyelids and spread his fingers against his chest. “Oh, this? This is nothing. The good stuff’s in the safe.”

To Winn, Daphne was a foreign being, a sort of mystic, a snake charmer or a charismatic preacher, an ambassador from a distant frontier of experience. The academic knowledge that she was the product of his body was not enough to forge a true belief; he felt no instantaneous, involuntary recognition of her as flesh and blood. Not for lack of trying, either. He had changed her diapers and held her while she cried in the night and spooned gloopy food into her mouth, and certainly he loved her, but she only became more and more strange to him as she got older, and his love for her gave him no comfort but instead made him alarmingly porous, full of hidden passageways that let in feelings of yearning and exclusion. Sitting behind the paper, he imagined with trepidation a house populated by two Daphnes, a Biddy, and only one Winn.

“Daddy,” came the piping voice from across the table, “am I a princess?”

“No,” Winn said. “You’re a very nice little girl.”

“Will I be a princess someday?”

Winn bent the top of the newspaper down and looked over it. “It depends on whom you marry.”

“What does that mean?”

“Well, there are two ways for a woman to become a princess. Either she’s born one, or she marries a prince or, I think, a grand duke—although I’m not sure those exist anymore. You see, Daphne, many countries that used to have princesses don’t anymore because they’ve abolished their monarchies, and an aristocracy doesn’t make sense without a monarchy. Austria, for example, got rid of all that business after the First World War. Hereditary systems like that aren’t fair, you see, and they breed resentment among the lower classes. Anyway, the long and short of it is, since you weren’t born a princess, you would need to marry a prince, and there aren’t very many of those around.”

Reproachfully, she ate a grape and then wiped her fingers one at a time on a napkin. He returned to reading.

“Daddy.”

“What?”

“Am I your princess?”

“Christ, Daphne.”

“What?”

“You sound like a kid on TV.”

“Why?”

“Because you’re full of treacle.”

“What’s treacle?”

“Something that’s too sweet. It gives you a stomachache.”

She nodded, accepting this. “But,” she pressed on, “am I your princess?”

“To the best of my knowledge, I don’t have any princesses. What I do have is a little girl without any dignity.”

“What’s dignity?”

“Dignity is behaving the way you’re supposed to so people respect you.”

“Do princesses have dignity?”

“Some do.”

“Which ones?”

“I don’t know. Maybe Grace Kelly.”

“Who is she?”

“She was a princess. First she was an actress. Then she married a prince and became a princess. In Monaco. She was killed in a car accident.”

“What’s Monaco?”

“A place in Europe.”

Daphne took a moment to absorb and then asked, “Am I your princess?”

“We’ve just been through this,” Winn said, exasperated.

She looked like she was trying to decide whether her interests would be better served by smiling or crying. “I want to be your princess,” she said, teetering toward tears. Daphne was an accomplished crier, plaintive and capable of great stamina. For a girl so physically delicate and soft in voice, she was unexpectedly stalwart in her emotions. Her tears were purposeful, as were her smiles and pouts. Biddy called her Lady Macbeth.

Ducking back behind his paper, Winn did what was necessary. “All right,” he said. “Daphne, you are my princess.”

“Really?”

“Absolutely.”

Daphne nodded and ate a grape. Then she cocked her head to one side. “Am I your fairy princess?”

Biddy, when Winn went looking for her, was getting out of the shower. Through the closed door he heard the water shut off and the rattle of the shower curtain. She was humming something to herself. He thought it might be “Amazing Grace.” Knocking once, he pushed open the door, releasing a cloud of steam. Her bare body, flushed from the shower, was so close he could feel the heat coming off her back and small, neat buttocks. A foggy oval wiped on the mirror framed her breasts and belly button, the dark badge of hair below, his tight face hovering over her shoulder. After fall stripped away her summer tan, her skin tended toward a certain sallowness, but the hot water had turned her chest and legs a rosy pink. Already, her breasts looked swollen. A white towel was wrapped around her head. Her reflection smiled at him. Biddy, he had planned to say, maybe one is enough. He would suggest they sit down and make a pros and cons list. He was holding a yellow legal pad and a blue pen and had already thought of cons to counter all possible pros.

“What is it?” she asked, her smile draining away. He wondered if she had already guessed that he had trailed her to this warm, foggy room to argue her baby away from her. She had some lotion in her hand, and he watched her rub it on her sides and stomach, across stretch marks from Daphne that were only visible in the pale months. “Winn?” she asked. “What?”

“What was that you were just humming?” he asked.

“‘Unchained Melody,’” she said.

“Oh.”

“And?”

“And what?”

She took another towel and wrapped it around herself, tucking in the end beneath her armpit. “What else?”

“Nothing important.”

“What’s that for?” She pointed at the legal pad.

“I needed to take some notes.”

“About what?”

“A work thing.”

She turned to the mirror and asked, almost casually, “Are you excited about the baby?”

Winn was silent.

“Are you?” Biddy prodded.

“Yes,” Winn said. “No.”

“No, you’re not excited?” She and Daphne had the same way of wrinkling their foreheads when their plans went awry. “What were you going to say when you came in here?”

He tapped the legal pad against his thigh. “I’m not sure.”

“Winn, out with it.”

“Fine. I was thinking about saying we shouldn’t jump into anything. We didn’t exactly plan this.”

“We always said we would have two.”

“We hadn’t talked about it in years. Maybe four years.”

“No, we talked about it last year. On Waskeke. At the bar in the Enderby. You said you’d like to try for a son.”

“We’d been drinking, and that was still a year ago.”

“I didn’t think it was empty talk. We always said we’d have two. I understood our plan was for two. We always said so.”

“I thought … I assumed, apparently incorrectly, that we’d both cooled on the idea.”

“You should have said if you’d changed your mind.”

“You should have said you wanted another one.”

“Let me ask you this, if you could know right now that it’s a boy, would we be having this conversation? Would you have made one of your lists? That’s what you have there, isn’t it?”

He hid the pad behind his back and soldiered on. “I didn’t know you’d gone off the pill,” he said. “Did you do it on purpose?”

She rummaged in a drawer. “I forgot for a week. I know you don’t like to be surprised, but I thought we wanted this. I thought if it happens, it happens. I didn’t realize you had changed your mind. You should have said something.”

“I didn’t know I had to. I didn’t realize I had given tacit approval to conceive a child at the time of your choosing.”

He stepped back in time to remove himself from the path of the slamming door. The bath began to run. Biddy’s sisters said that Biddy was drawn to water in times of need because she was an Aquarius. Winn put no stock in astrology—the whole concept was embarrassing—but he admitted that his wife’s passion for baths, showers, lakes, rivers, ponds, swimming pools, and the ocean was a powerful force. Biddy descended from a line of people who were at once remarkably unlucky and extraordinarily fortunate in their encounters with the sea. Since a grandfather many greats ago had managed to catch hold of a dangling line after being swept by a wave from the deck of the Mayflower and be dragged back aboard, her forebears had been dumped into the ocean one after the other and then, while thousands around them perished, been plucked again from the waves. A grandaunt had survived the sinking of the Titanic; a distant cousin crossed eight hundred miles of angry Southern Ocean in a lifeboat with Ernest Shackleton; her father’s cruiser was sunk at Guadalcanal, and he saved not only himself but three others from shark-infested waters. The grandaunt’s photograph, a grainy enlargement of a small girl wrapped in a blanket and looking very alone on the deck of the Carpathia without her nanny (who had gone to the bottom of the Atlantic) hung in their front hallway.

Whatever the root of Biddy’s affinity for water, as long as Winn had known her, she had been able to submerge herself and come out, if not entirely healed, at least calmed, her mood rubbed smooth. But he could not have anticipated that she would emerge from this particular bath and find him where he had settled with the newspaper in his favorite chair and announce that she was going to have a water birth for this baby.

“A what?”

“A water birth. You give birth in a tub of warm water. There’s a hospital in France that specializes in it. We’re going there.”

Winn felt an “absolutely not” pushing its way up his throat. He had married Biddy partly because she was not given to outlandish ideas, and he felt betrayed. But the rafters of the doghouse hung low over his head. “Sounds like some kind of hippie thing to me,” he said.

“I’ve done research. Candace McInnisee did it for her youngest, and she swears by it.”

“You did research before you knew you were pregnant?”

“We always said we would have two, Winn. And since you’re not the one giving birth, I don’t see why you should mind where it happens.”

Winn lifted his paper and let it fall, a white flag spreading on the floor in marital surrender. He held out his arms. She came close, leaned to kiss him on the forehead, and slipped away before he could embrace her.

LIVIA WAS BORN in France in a tub full of water, and she, like Biddy, had spent the years since her birth returning, whenever possible, to an aqueous state. She had once come home from a fruitful day in the fourth grade and declared that she was a thalassomaniac and a hydromaniac while Biddy was only a hydromaniac, which was true. Biddy’s love of water did not extend past the substance itself, whereas Livia loved all water but especially the ocean and its inhabitants. During her time at Deerfield, she had baffled Winn by organizing a Save the Cetaceans society and by spending her summers on Arctic islands helping researchers count walruses or on sailboats monitoring dolphin behavior in the Hebrides. She had passionately wished to join the crew of a vessel that interfered with Japanese whaling ships, but Biddy had managed to convince her that she would be more helpful elsewhere. Now she was studying biology at Harvard with plans for a Ph.D. afterward. She had made it clear to Winn that she thought his ocean-provoked existential horror was a bit of willful silliness. From the age of eleven, she had insisted on getting and maintaining her scuba certification and was always after Winn to do the same, though the idea held no appeal for him. He had snorkeled a few times and once swam by accident out over the lip of a reef, where the colorful orgy of waving, flitting life dropped into blackness. He felt like he had taken a casual glance out the window of a skyscraper and seen, instead of yellow taxis and human specks crawling along the sidewalks, only a chasm.

Winn had expected Livia’s passion for the ocean to fade away like her other childhood enthusiasms (volcanoes, rock collecting), but a vein of Neptunian ardor had persisted in the thickening stuff of her adult self. She spotted seals and dolphins that no one else noticed, and she was on constant watch for whales. A stray plume of spray was enough to get her hopes up, and after she had stopped and peered into the distance long enough to be convinced no tail or rolling back was going to show itself, she would blush and fall silent, seeming to suffer a sort of professional embarrassment. She claimed she would be happy to spend her life on tiny research vessels or in cramped submersibles, poking cameras and microphones into the depths as though the ocean might issue a statement explaining itself. His selkie daughter. How Livia could feel at home in a world so obviously hostile was beyond him, as was her willingness to lavish so much love on animals indifferent to her existence.

Daphne was the simpler of his daughters to get along with but also the more obscure. By the time she finished college, she seemed to have shed the serpentine guile of her infant self, or else her manipulations had grown so advanced as to conceal themselves entirely. He couldn’t be sure. A smoked mirror of sweetness and serenity hid Daphne’s inner workings, but Livia lived out in the open, blatantly so, the emotional equivalent of a streaker. Livia’s problem was a susceptibility to strong feelings, and her strongest feelings these days were about a boy, Teddy Fenn, who had thrown her over. She had seen too many movies; she did not understand that love was a choice, entered and exited by free will and with careful consideration, not a random thunderbolt sent from above. He had told her so, but she would not listen. She was angry at the world in general and Winn in particular, so he was angry with her in return. In the interest of familial peace, he would try to put everything aside for the wedding, and perhaps Waskeke would exert a healing influence, bring her back to herself.

He needed to buy more groceries for dinner and to deliver Biddy’s lunatic flowers to the Enderby, where the Duffs were staying. With the aim of forging an alliance, he sought out Livia to see if she would come along. She was in the bathtub.

“It’s after two,” he said through the door, “so the sooner we go the better.”

“Where’s Celeste?” Livia asked.

“Up on the roof.”

“Communing with the vodka gods?”

“And with your mother.”

A splash. “Give me a minute.”

They rattled back down the driveway in the old Land Rover, the Duffs’ flowers blooming up from between Livia’s knees like a Roman candle.

“What do you say we take the scenic route?” Winn said, pausing at the road.

She shrugged. “I thought we were in a hurry.”

Only to get out of the house, he thought. In the hour since his arrival, he had managed to offend Biddy by suggesting that all the test runs with makeup and hair and such were an extravagance and also to walk in on Agatha in the downstairs bathroom. He hadn’t seen anything, only her surprised face and bare thighs (the gauzy white dress concealed their crux) and a wad of toilet paper clutched in her hand, nor had he said anything, which made the situation worse. He had closed the door—not slammed it but closed it quietly and deliberately—before fleeing up to the widow’s walk to tell Biddy he was going to the market.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.