Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «A Scandalous Life», sayfa 2

Rear Admiral Digby

Casa Brunavini

Florence, Italy

Florence, Thursday

Dearest Papa,

I write because I have a favour to ask which I am afraid you will think too great to grant; but as you at Geneva trusted me with [a] littler sum I am not ashamed, after you have heard from Steely my character, to ask a second time.

It is to … to … to advance me my pocket money, two pounds a week for 20 weeks counting from next Monday and I’ll tell you what for! If you approve I’ll do it but if not I’ll give it up!!!

Remember at Geneva after you advanced me 12 weeks, I never teased you for money until the time was expired. I promise to do the same here. Do not tell anyone but give me the answer. I will not ask for half a cracie until the time is expired. Think well of it and remember it is 20 ! ! ! weeks; I ask 40 pounds ! ! ! ! Not a farthing more or less. 40 pounds.

Goodbye and put the answer at the bottom of this [note]. I have long been trying to hoard the sum but I find that I want it directly and then I should not have it till we were gone. If you repulse me I will not grumble and if you grant it me ‘je vous remercie bien’. Pensez y and goodbye, mon bon petit père, I remain your very affectionate daughter.

Jane Elizabeth Digby20

Unfortunately the surviving note lacks Admiral Digby’s response, and it is impossible to guess at the childhood desire that prompted such a request, or whether it was granted.

At the age of fifteen Jane was sent off to a Seminary for Young Ladies near Tunbridge Wells, Kent, for finishing. Here, in the traditions of English public school life, Jane fagged for an older girl, Caroline ‘Carry’ Boyle, during her first year.21 She missed her family but not unusually so, and to compensate she became a frequent correspondent, especially with her brothers, of whom she was very fond. Their notes to each other were partly written in the ‘secret’ code which she would use freely in her diary throughout her life.22

There was a good deal to write about. Their grandfather Coke, only a year short of seventy, decided to remarry in February 1822. His bride, Lady Anne Keppel, was an eighteen-year-old girl, the daughter of a family friend, Lady Albemarle (who had died at Holkham in childbirth some years earlier), and god-daughter to Mr Coke. Furthermore, since Lady Anne’s father married a young niece of Mr Coke’s at the same time, there was a good deal of speculation that Lady Anne had married merely to escape from home.

Soon afterwards, Coke’s youngest daughter, Elizabeth (Eliza), who had reigned at Holkham as chatelaine while her father was a widower, married John Spencer-Stanhope and finally left the family home.

When Jane Digby left school at Christmas 1823, she was – as the French writer Edmond About wrote – ‘like all unmarried girls, a book bound in muslin and filled with blank white pages waiting to be written upon’.23 She was also a lively, self-confident young woman who adored her parents and was not above teasing her papa with humorous affection when she came upon a ‘quaint’ tract on his desk entitled ‘Hooks and Eyes to keep up Falling Breeches’.24

It had already been decided by ‘dearest Madre’ that Jane would make her début in the following February when the season started, rather than wait a further year. There is an unsubstantiated story that Jane was romantically attracted to a Holkham groom,25 and that an attempted elopement precipitated her early entry into society; however, according to her poems, Jane had thoughts and eyes for no one during these months but her handsome eldest cousin George Anson. It is doubtful that George, one of the most popular men about town, gave Jane more than a passing thought, for he was busy sowing his wild oats with married women; the hero-worship directed at him by his cousin was totally unrequited. Besides, there was a family precedent for early entry into society. Jane’s Aunt Anne was betrothed at fifteen, and made her début a year later.

Though no longer required in the role of governess, Steely remained as Jane’s duenna, to chaperon her during her forthcoming season when Lady Andover was engaged elsewhere. Miss Jane Steele continued to provide drawing lessons.

Had they been told that Jane would hardly be out of her teens before she would appear in one of the most sensational legal dramas of the nineteenth century, making it impossible for her ever again to live in England; that she would be so disgraced that her doting maternal grandfather Coke would cut her out of his life, and her uncle Lord Digby would cut her brother Edward (heir to the title Lord Digby) out of his will; that she would capture the hearts of foreign kings and princes, but would abandon them to live in a cave as the mistress of an Albanian bandit chieftain; that in middle age she would fall in love and marry an Arab sheikh young enough to be her son, and live out the remainder of her life as a desert princess, the Misses Steele could not possibly have believed it. Yet all those things, and much more, lay in the future for Jane Digby.

2 The Débutante 1824

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Jane was not a stranger to London. Her parents owned a house on the corner of Harley Street ‘at the fashionable end’,1 so she would not have arrived wide-eyed at the bustle and noise noted by so many débutantes. However, as a girl who had not yet been brought out into society, the time she had previously spent there would have been very tame.

When not in the schoolroom Jane would spend her days shopping with her mother in the morning, if the weather permitted walking. In the afternoon she might walk in Hyde Park, chaperoned by Steely, and paint in watercolours or practise her music at other times. Jane and her brothers would have eaten informal meals with their parents, but for dinners and parties they would have been banished to the nursery – a far cry from Holkham, where the children often mingled with the adults. In town it was not possible for Jane to walk round to the stables and order her horse to be saddled for an invigorating gallop. It was necessary to appoint a given time for the horse to be brought round to the house, and it would be a solecism if a girl not yet out in society or even one in her first season went for a gallop in the park.

But all this changed when she took London by storm. The change to her life was an intoxicating experience. Now she breakfasted late with her parents and, while she might still shop with her mother in the mornings, it was for clothes and fashionable fripperies for her town wardrobe: new silk gloves or satin dancing slippers, an embroidered reticule for walking out, a domino for a masked rout, white ostrich feathers for her presentation, some ells of white sprigged muslin. Now she attended lessons in the cotillion and the waltz, given by a dancing master under Steely’s watchful eye. Now she rode her neat cover-hack in the park at the fashionable hour of 5 p.m., or rode with her mother in the chaise in Rotten Row, nodding to acquaintances, stopping for a chat with friends. Now the florist’s cart was never away from the door with small floral tributes from admirers.

The years of instruction by Steely at last bore fruit. Jane’s natural ear for languages enabled her not only to infiltrate foreign phrases into her conversation and correspondence – the outward sign of a well-rounded education – but also to converse in Italian, French and German with foreign visitors. All those music lessons that Jane had found a dreary bore were now justified, for after a dinner party she might be called upon to perform for her fellow guests. She was a good pianist, and played the guitar and lute; she also had a sweet singing voice. She acquired a wide repertoire of foreign love songs, which generally delighted her listeners. She was not slow to recognise when she captivated her hearers, and was feminine enough to enjoy doing so.2

At sixteen, however, Jane was younger than the average débutante and had little experience of life. But she realised quite quickly that what was acceptable behaviour in the country was not so in London. A young lady might never venture abroad alone, on foot without a footman, or on horseback or in a carriage without a groom in attendance. She might, by 1824, have shopped with a girlfriend in Bond Street without raising eyebrows, just; but no lady would be seen in the St James’s area where the gentlemen’s clubs were situated. A young unmarried woman could never be alone with a gentleman unless he was closely related, and, while she might drive with a gentleman approved by her mama in an open carriage in the park, it must be a safe gig or perch phaeton and not the more dashing high-perch phaeton affected by members of the four-horse club, nor the newest Tilbury driven tandem. Either of the latter would have branded a girl as ‘fast’, even with a groom acting as stand-in for a chaperone. At a ball she must not on any account stand up to dance with the same man more than twice. The merest breath of criticism against a girl or her family was enough to prevent her obtaining a voucher from one of the Lady Patronesses of Almack’s.3

Despite the high standards they set for patrons of Almack’s it would be fair to say that the private lives of most of the Patronesses would not stand close examination, for with one exception they all had famous affaires with highly ranked partners ranging from the Prince Regent himself to several Prime Ministers; however, they maintained a discreet appearance of respectability – a pivot, as it were, between the open licentiousness of the Regency and the rapidly approaching hypocrisy of Victorian morality.

Not to be seen at Almack’s branded one as ‘outside the haul ton’, so that, in effect, the Patronesses constituted a matriarchal oligarchy to whom everyone bowed, including the revered Duke of Wellington, who was turned away one evening for not wearing correct evening dress. Captain Gronow, the contemporary social observer, wrote: ‘One can hardly conceive the importance which was attached to getting admission to Almack’s, the seventh heaven of the fashionable world. Of the three hundred officers of the Foot-Guards, not more than half a dozen [Captain Gronow was one of those] were honoured by vouchers.’ Almack’s was a hotbed of gossip, rumour and scandal, and the country dances were dull. Matters improved somewhat after Princess Lieven and Lord Palmerston made the waltz respectable, though it was still regarded by many parents as ‘voluptuous, sensational … and an excuse for hugging and squeezing’.4 Alcoholic drinks were forbidden, and refreshments consisted of lemonade, tea and cakes, and bread and butter.

Why entrance to so prosy a venue should excite such passion, when the London season offered dozens of more exciting and enjoyable occupations every evening, can be explained by the fact that Almack’s was the most exigent marriage market in the Western world,5 and marriage was what the whole thing was about. It was desirable for a young man of decent background and respectable expectations to attract favourable connections through marriage, and if the wife had a good dowry so much the better. But it was essential for a young woman to contract an eligible match with a man who could provide all the social and financial advantages that she had been reared to take for granted. The lot of an unmarried woman past her youth in that milieu was unenviable – thrown, as it were, on to the charity and tolerance of her relatives. Jane Austen’s heroines exemplify, with a touching contemporary immediacy, the importance of a woman ‘taking’ duringdeher début.

Vast wardrobes of morning dresses, afternoon dresses, walking-out dresses, ballgowns, riding habits and gowns suitable for every conceivable occupation were necessary. But cloaks and gowns were only the start. Accessories, such as collections of hats ranging from the simple chipstraw to high-crowned velvet bonnets, were indispensable. Gloves of silk, lace, satin and kid for every occupation that might be fitted in between rising and retiring, from walking to riding to dining and dancing, were essential. Sandals, reticules, shawls, tippets, fans, chemises, camisoles and undergarments such as stays were obligatory. All of this, with luck, would form the basis of a girl’s trousseau in due course. Further expenditure included the cost of a good horse for riding in Hyde Park (a prime shopwindow in the marriage market) and the use of a carriage, since it was no use expecting a girl to travel everywhere by sedan chair. If the parents had no town-house of their own, and no relative with whom to stay, they must also bear the cost of hiring a house for the season as well as organising several smart dinner parties and soirées, and at least one ball. It was a huge investment, and this can only have served to heighten the pressure on the girl to fix the interest of a suitable man.

Jane made her début at a royal ‘Drawing Room’ in March 1824, when Lady Andover introduced her daughter to King George IV and the fashionable world. Henceforward Jane was an adult, free to attend adult parties and dances. With her background, connections and appearance, it was inevitable that she would be an immediate success. Her aunt, Eliza Spencer-Stanhope, wrote to the family that her sister, Lady Andover, was ‘graciously’ anticipating imminent conquests.6

Vouchers for Almack’s were, of course, forthcoming for Lady Andover and her fledgeling, and Jane was subsequently to be seen at every ball, soirée, rout and dinner party of note. Young admirers wrote poems to her eyes, her shoulders, her guinea-golden curls; and she replied by telling ‘her wooers not to be “so absurd”’.7 No new entry truly made an impression unless a nickname attached itself to her; ‘the Dasher’, ‘the White Doe’ and ‘the Incomparable’ were typical. Jane became known as ‘Light of Day’.

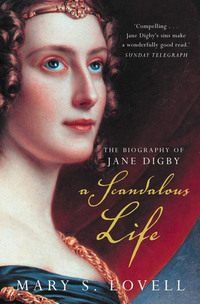

The pencil and watercolour sketch made of Jane in 1824 shows her hair springing prettily from her high forehead, curling naturally into small ringlets around her face and coiled into a coronet. Large eyes fringed by thick dark lashes gaze serenely at the viewer and the sweet expression which might otherwise be serious is lifted by curved full lips. What the sketch does not convey is Jane’s colouring; oil portraits show that her hair was a rich tawny gold, her eyes dark violet-blue, and her fine clear skin a delicate pink. The sketch does not portray her figure (described by many diarists as ‘perfect … instinctive with vitality and an incomparable grace of movement)’,8 nor that when her pink lips parted her teeth were like ‘flawless pearls’.9 She had a roguish smile, a soft light voice and a pleasing modesty which gave way to lively animation once initial shyness had been overcome.

George IV was no longer the handsome Prince Regent of yesteryear but a tired and corpulent old man who walked with a stick. Nevertheless Jane must have enjoyed the thrill of the occasion. She wore the uniform white silk gown of simple cut, high-waisted with tiny puff sleeves, a sweeping train falling from her slim shoulders, long white gloves, and the de rigueur headdress of three white curled ostrich feathers. Small wonder that within days of her daughter’s presentation Lady Andover was so certain of a conquest that it was being noted in family correspondence. Small wonder that within a matter of weeks the youthful admirers who shoaled around Jane were scattered by a shark attracted into Jane’s pool of suitors.

Edward Law, Lord Ellenborough, was no stranger to Jane. She had met him at least once some four years earlier when he had sided with Thomas Coke in opposing the King’s wish to divorce. As a consequence Ellenborough had visited Holkham, though at that time Jane was a mere twelve-year-old occupant of the schoolroom. Now, creditably launched into society, although very young she was considered by many to be one of the catches of the season.

Ellenborough was thirty-four, a widower, childless, and by any standards eligible in the marriage market. He was rich and pleasant-looking, with a polished address, having been educated at Eton (where he was known as ‘Horrid Law’, and generally regarded as ‘prodigious clever’),10 and Cambridge. He had wanted a military career but his father, a former Lord Chief Justice in the famous post-Pitt ‘All the Talents’ coalition government, forbade it, so he entered the world of politics. By 1824 Edward, who succeeded to the title in 1819, had every anticipation of a Cabinet position. His late wife Octavia had been sister to Lord Castlereagh – Ellenborough’s political mentor – and The Times report of her funeral reflects their status:

At an early hour yesterday, the remains of Lady Ellenborough were removed from his Lordship’s house in Hertford Street, Mayfair. The cavalcade moved at half-past 6, and consisted of four mutes on horseback, six horsemen in black cloaks etc.

The hearse, containing the body enclosed in a coffin covered with superb crimson velvet, elegantly ornamented with silver gilt nails, coronets etc. and with a plate bearing the inscription; ‘Octavia, Lady Ellenborough, daughter of Robert Stewart, Marquis of Londonderry died the 5th of March 1819, aged 27’; was followed by five mourning coaches and four, with several carriages of the nobility etc.11

Five years had passed since Lady Octavia’s untimely death. Meanwhile her brother had become the most hated politician of the day, and ended his life in 1822 by slitting his throat with a penknife. Probably England’s forty years of peace after Napoleon’s downfall owed much to Castlereagh’s period as Foreign Secretary,12 yet he was so despised that his coffin was greeted with shouts of exultation as he was borne to his grave in Westminster Abbey. Some of that odium still clung to Lord Ellenborough. Further, Ellenborough’s championship in 1820 of the former Queen Caroline’s cause, and a major speech in 1823 during a debate on the King’s Property Bill seeking to reduce George IV’s powers to dispose of Crown property, had permanently alienated his sovereign and made him persona non grata at court. Nevertheless Lord Ellenborough was a rising power in the land, despite whispered hints and rumours that he had some murky secrets in his private life and that he had been refused by several respectable young women.

Jane and Lord Ellenborough met in early April around the time of Jane’s seventeenth birthday, possibly at Almack’s. Less than eight weeks later Ellenborough sought permission from Admiral Digby to address Miss Digby (he always called her Janet) and a week later, on 4 June, Coke’s friend Lord Clare was writing to a mutual acquaintance, ‘I hear Ellenborough is going to be married to Lady Andover’s daughter.’13

They were a handsome couple and each had much to offer a partner, but there was an obvious disparity in age and experience. Ellenborough was twice as old as Jane and a friend of her father, though at thirty-four he was hardly the raddled ancient roué that some Digby biographers have implied.14 The difference in years is anyway of questionable importance when within Jane’s own family there was ample evidence that April could successfully marry December. However, Ellenborough was an ambitious and mature politician who had little time to spare for social obligations unless they might further his work or career, and even less to cherish and instruct – let alone amuse – a child bride. Here was a man who, when obliged to entertain, would inevitably fill his table and his guest rooms with minor members of the royal family, ambassadors and senior politicians.

Jane was a young girl who only a few weeks earlier would have needed her governess’s permission even to ride her horse. This marriage would place her at a stroke in charge of an elevated domestic establishment, hostess to the country’s leaders and responsible for dozens of servants. Jane’s family connections were considerable, but Ellenborough had no need of them to further his career. Perhaps he fell in love with the enchanting girl, or at least was so charmed with her that he was willing to overlook her lack of experience. He desperately wanted an heir and her family had a record of healthy fecundity. It was said that he ‘courted her with the impatience and persistence of an adolescent boy’.15

That Jane chose to marry Lord Ellenborough when, to judge from her family’s correspondence, she might have chosen a bridegroom nearer her own age is equally surprising. Previous biographers have speculated that Jane was compelled to marry Ellenborough by her parents, but there is no evidence to substantiate this. Jane could twist her father – whom she called ‘darling Babou’ – round the proverbial little finger, as surviving letters show, and it would have been out of character for either of her doting parents to coerce Jane into an unwanted marriage. Furthermore, Jane was so young that, even had she not found a match she liked in her first season, she could have returned again – as many girls did – for a second shot, still not having reached her eighteenth birthday. It seems far more likely that she was flattered by the attentions of an older, experienced man and that she romantically concluded that she was in love with him. This is borne out by poems that the couple sent each other, and by subsequent entries in Jane’s diaries. One of Lord Ellenborough’s poems tells of Jane’s love for him:

O fairest of the many fair

Who ruled, or seemed to rule my heart

The first I have enthroned there

Without a wish my bonds to part.

The thought that I am loved again

And loved by one I can adore,

That I have passed through years of pain

And found the bliss I knew before.

O ’twould have ta’en away my mind

But thy sweet smile a charm has given

And love’s wild ecstasy combined

With deepest gratitude to heaven.16

His Lordship’s other poems spoke of ‘joy in the present day’ because of her and the bliss of knowing that ‘the next will be yet happier than this … Oh! this is youth and these the dreams of youth … And heaven itself is realised on earth.’17

During their whirlwind courtship society found a synonym for Jane’s sobriquet ‘Light of Day. ‘Aurora’ was a name with which Jane could not have found fault in view of the fact that her father had once captained a ship of the same name, and it had a pretty sound. However, it was almost certainly intended to be less flattering to her suitor, Jane being cast in the role of Lord Byron’s sixteen-year-old heroine Aurora Raby, with Lord Ellenborough as the debauched, ageing, eponymous subject of the best-selling Don Juan:

there was indeed a certain fair and fairy one

Of the best class and better than her class,

Aurora Raby, a young star who shone

O’er life, too sweet an image for such glass.

A lovely being, scarcely formed or moulded,

A rose with all its sweetest leaves yet folded.18

It was not to be supposed because of the speed of the courtship that the marriage could be held with similar haste. During June the engaged couple enjoyed the last days of the season with its military reviews, balloon ascents, race meets and ridottos. As his fiancée Jane could ride publicly in Lord Ellenborough’s glossy phaeton, with his groom in attendance. She must be introduced to her prospective in-laws, Edward’s sister Elizabeth and his brothers, Charles and Henry. There were also the Londonderrys, his former in-laws, a valuable relationship he wished to maintain. When Lady Andover received a letter from Lady Londonderry congratulating her upon Jane’s betrothal and eulogising Lord Ellenborough,19 it must have been comforting to know that her cherished daughter was to marry such a paragon.

At the end of July, Edward visited Holkham, where he met the Cokes, Digbys, Ansons and Spencer-Stanhopes.20 It was not his first visit, but Jane must have derived immense pleasure from showing him some of the treasures of the great house, and riding with him in the parkland bordering the beaches. However, Edward and Mr Coke, having once been allies, had now moved apart politically; consequently his future visits to Holkham, and eventually Jane’s own, were few.

Shopping and fittings for the bridal clothes were time-consuming, and Jane must be taken over her future homes – an elegant pillared and porticoed town-house in Connaught Place, whose rear windows today overlook Marble Arch, and Elm Grove, Lord Ellenborough’s country house at Roehampton near Richmond.21 Yet somehow, during this time, Jane must have been instructed in her duties as chatelaine, for, although she would have had domestic instruction as she grew up, she would have had little reason to put such knowledge to practical use. Her mother wrote a treatise, which subsequently served as a model for other brides-to-be within the Coke family, upon the qualities requisite for ‘members of the household’, including that most valuable servant, the Lady’s maid:

Essentials for a Lady’s maid

She must not have a will of her own in anything, & always be good-humoured and approve of everything her mistress likes. She must not have an appetite … or care when or how she dines, how often disturbed, or even if she has no dinner at all. She had better not drink anything but water.

She must run the instant she is called whatever she is about. Morning, noon and night she must not mind going without sleep if her mistress requires her attendance. She must not require high wages nor expect profit from old clothes but be ready to turn and clean them … for her mistress, and be satisfied with two old gowns for herself. She must be a first-rate vermin catcher.

She must be clean and sweet … let her not venture to make a complaint or difficulty of any kind. If so, she had better go at once.22

Few of Jane’s papers from this period survive and her journal is not among them. We know, however, that her parents were delighted with the match, and that Steely approved also. But there were some dissensions, notably among Ellenborough’s political opponents. One could not accuse the Duke of Wellington’s chère amie, Harriet Arbuthnot, of political bias, however, when she wrote that ‘Ellenborough having flirted and made himself ridiculous with all the girls in London now marries Miss Digby … she is very fair, very young and very pretty.’23 The diarist Thomas Creevey, who was a close friend of Jane’s aunt Lady Anson and knew Ellenborough well, wrote:

Lady Anson goes to town next week to be present at the wedding of her niece, the pretty ‘Aurora; Light of Day’ Miss Digby … who is going to be married to Lord Ellenborough. It was Miss Russell who refused Ld Ellenborough, as many others besides are said to have done. Lady Anson will have it that he was a very good husband to his first wife, but all my impressions are that he is a dammed fellow.24

Lady Holland wrote to her son that Ellenborough ‘has at last succeeded in getting a young wife, a poor girl who has not seen anything of the world. He could only snap up such a one … she is granddaughter of Mr Coke who has another son!’25 Thus she broke the news that Jane’s grandfather had the felicity of a spare for his cherished heir. However, Lady Holland’s views on Lord Ellenborough were politically jaundiced; she disliked him intensely and openly held the opinion that he was impotent.26

In August, Ellenborough noted in his diary that he had ‘dined with Janet at the Duke’s’. The Duke of Wellington’s London home was Apsley House, near Hyde Park. It was a huge formal dinner with many notables present, all much older than Jane. Ellenborough was clearly pleased at the manner in which Jane conducted herself in such august company.27

The day designated for the marriage was 15 September 1824, some five months after their meeting in London. The venue was not, as might be supposed, the chapel at Holkham; with a new son only three weeks old, Jane’s step-grandmother could not accommodate a wedding party. Jane was married to Edward at her parents’ London house, as an entry in the register of the Parish of St Marylebone shows:

The Right Honourable Edward Lord Ellenborough, a Widower, and Jane Elizabeth Digby, Spinster, a minor, were married by Special Licence at 78 Harley Street by and with the consent of Henry Digby Esquire, Rear Admiral in His Majesty’s Navy, the natural and lawful father of the said minor, this fifteenth day of September.28

It was not unusual for a society marriage to be conducted in a private home. Slightly more unusual, perhaps, was that it was performed in a secular venue by a bishop, Edward’s uncle, the Bishop of Bath and Wells. The court pages reveal that the happy couple sped off to Brighton for the honeymoon where, as Jane recalled many years later, a wholly satisfactory wedding night followed.29