Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Cloven Hooves»

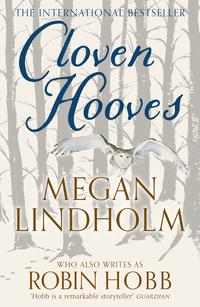

CLOVEN HOOVES

Megan Lindholm

Who also writes as

Robin Hobb

Copyright

HarperVoyager

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1993

Copyright © Megan Lindholm Ogden 1991

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover illustration © Jackie Morris

Robin Hobb writing as Megan Lindholm asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008287399

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008363956

Version: 2019-06-07

Praise

‘Hobb is one of the great modern fantasy writers … As addictive as morphine’

The Times

‘A little slice of heaven’

The Guardian

‘The feelings of anguish, ambiguity, fear and failure [in her novels] are as familiar as those in a novel by Jonathan Franzen’

Independent on Sunday

‘Hobb is always readable. But the elegant translucence of her prose is deceptive … That is the ambition of high art. The novelists in any genre are rare who achieve it with Hobb’s combination of accessibility and moral authority’

Sunday Telegraph

‘A series that recalls HBO’s Game of Thrones, and The Lord of the Rings’

The Telegraph

‘In today’s crowded fantasy market Robin Hobb’s books are like diamonds in a sea of zircons’

George R.R. Martin

‘Hobb is superb, spinning wonderful characters and plots from pure imagination’

Conn Iggulden

‘Magic is the word. Absolutely riveting’

Barbara Erskine

‘Hobb seamlessly blends intrigue, action and characters who feel so real that they become more than words on a page’

SFX

‘Glorious and beautiful storytelling from Robin Hobb’

SciFi Now

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

About the Author

By Robin Hobb

About the Publisher

ONE

In Flight

11 March 1976

I turn away from staring out the window, lean over to check my child in the seat beside me. There’s nothing to see out there, anyway. Outside the oval airplane window, a night sky jets soundlessly by. Overcast covers all but a few stars. Nothing to keep my mind from chewing on itself. Inside is the sound of the engines, of the tiny seat fans whirring as they stir the stale air. Rows of red upholstered seat backs, backs of heads. Most of the overhead seat lights are off. Tiny airline blankets are tucked around the shoulders of some dozing passengers. Others read newspapers and magazines, smoke, or talk softly to seatmates. A few drink industriously. Nothing in here to keep my mind busy, either.

Teddy is asleep. He had asked for the window seat, and of course we had given it to him, even though we knew there would be little to see on this night flight from Fairbanks, Alaska, to the Sea-Tac Airport in Washington. Still, he got to watch the tower and runway lights vanish away beneath us, caught a brief glimpse of the lights of some little town down there a while later. Then he used the airplane’s bathroom twice, giggled over finding the barf bag in the seat pocket, got a coloring book and crayons and plastic pilot wings from a stewardess, colored for a while, and got bored and wiggled for a while. And now, finally, he is asleep. I carefully move his copy of Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are because the corner of it is digging into his cheek. I give a sigh of relief that is partially anxiety. With Teddy dozing, there is nothing to distract me from my worrying. Except Tom. I turn my attention away from my five-year-old son and to my husband.

Who is also asleep in his seat on the other side of me.

Light hair is falling over his forehead. He breathes softly, evenly, at peace with the world and himself. I know I should let him rest. This is the horrible leave-Fairbanks-in-the-middle-of-the-night, -arrive-in-Seattle-too-early-to-be-awake flight. I should let him sleep, so he will be fresh and alert when his parents come to meet us at the airport. I shouldn’t wake him just to talk to me and reassure me. I really should let him sleep.

But I touch his hair lightly back into place. He smiles, and without opening his eyes, his hand comes up to hold mine. For a time we are silent, shooting through the night. Strangers occupy other seats around us, and doze or smoke or read papers or sip drinks. But Tom and I are alone among them. It is something we have always been able to do, make a quiet, private space around ourselves, no matter what the circumstances.

“Still worrying?” he asks me softly. His eyes remain closed.

“A little,” I admit.

“Silly.” His hand squeezes mine briefly, then relaxes again. He sighs, shifts in his seat to face me. He leans his face against the seat back while he talks to me, as if we were in our bed at home, lying face-to-face, heads on pillows, talking. It makes me wish we were, that I could snug my body up against his and hold him while he talks. He speaks softly, his deep voice soothing as a bedtime story. “We’re going to have a good time. Well, you will, anyway. I’ve got to fill in on the farm and in the shop until Bix’s shoulder heals. Fields to plow, tractors to fix. But you and Teddy will have a great time. Teddy’s going to have the farm to run around on. Eggs to gather, chicks, ducklings, pigs, all that stuff. And my mom and sisters are going to love having you. Ever since I married you, Mom and Steffie have been dying to get their hands on you. Go shopping, introduce you around. Steffie had so many plans when I talked to her on the phone, I don’t know how you’ll keep up with her.” He smiles at the thought of his younger sister.

I edge closer in my seat, lean my head close to his. “That’s just it. I don’t know how I’ll keep up with her, either.” I think of Steffie as I last saw her, on a brief Christmas visit two years ago. She had been just out of high school that year. She’d come home from some party, into the living room of the farmhouse, dressed in a dark green velvet sheath and high black heels, begemmed at ear and throat and wrist. Like a magazine cover come to life, but rushing to hug us, to say she was so glad we’d been able to fly down for Christmas. The memory reawakens in me the same twinge I’d felt then: awe at her beauty, and a shiver of fear.

Why?

Because she was so beautiful, so perfect. The ugly little jealousy that beautiful women always awoke in me had stirred. That she was Tom’s own sister hadn’t mattered. It wasn’t a sexual kind of jealousy. It was the knowledge that I could never compete with women like that, that I’d never learned to be elegant and feminine and charming and stunning and all those other adjectives that Steffie and Mother Maurie embodied so easily. Yet these were the type of women that Tom had around him when he was growing up. How could he have settled for a mouse like me? What if he woke up one day and realized he’d been cheated?

I tune in suddenly that Tom is still talking. “Steffie and Ellie love you. Mom and Dad think you’re great. Of course, I think a lot of that is that they were amazed that any woman at all would have me. Probably secretly grateful you married me and whisked me off to Alaska and out of their hair.”

He is teasing, of course. No one could ever wish to be rid of him. Tom is as perfect a product as Steffie is, tall and handsome and muscled, charming and kind and intelligent. Tom could have had his pick of women. I am still mystified that he chose me. But he did. And six years of marriage have taught me that I can believe in that miracle. So I can say to him, honestly, “I’m just afraid I’ll do something wrong. Put my foot in my mouth, spill soup in my lap. We’ve never stayed a month with them before, Tom. That’s a long time to live in someone else’s house, see them every day. I don’t know how I’ll handle it.”

He refuses to share my worry. “You’ll handle it just fine. They’ll love you just like I do. Besides, we’ll be in the little guest house. You’ll have time to yourself. I know you aren’t into socializing all the time. They’ll understand when you need to be alone.”

He believes it. There’s no mistaking the calm assumption in his voice. I wish I could.

He senses my doubt. “Look, Evelyn, it’ll be easy. Just let them make a fuss over you. They’ll love that. Go shopping. Get your hair done, buy some earrings, do, oh, I don’t know, whatever it is that women do together. You’ll have a great time.”

I look down at my sedate black skirt that matches my sedate black jacket that covers my simple white blouse. I think of the jeans and sweatshirts and sneakers in my luggage. I try to imagine shopping with Steffie. Green velvet. Sparkling earrings. The images don’t fit. “I’ll try,” I say doubtfully.

“I know. You’ll do fine.” He squeezes my hand again, leans back in his seat.

“What about your dad?” I say softly.

Tom grins suddenly. “That old fart still got you buffaloed? Look, Evelyn, it’s a big front. Just stand up to him and give him the same shit right back. He’ll only push you as far as you let him. I found that out a long time ago.”

“That’s easier said than done,” I mutter disconsolately, remembering his father’s piercing black eyes and square jaw. “Kinda skinny, ain’t she?” he’d remarked loudly to Tom the first time we were introduced. I’d stood still, too stunned to speak, until Mother Maurie shook my hand merrily and said, “Oh, don’t mind him, he’s just teasing.” But I hadn’t seen any laughter in his eyes. Only evaluation, like I was a heifer Tom had brought home for breeding stock. “He scares me,” I confess.

Tom laughs softly. “Only because you let him. Hey, he’s had to be that way to get where he is. If he hadn’t been direct and assertive, and pushed people for all he could get out of them, he’d still be plowing the back forty and trying to pay off the mortgages. He pushes. I know that. But it’s not like it’s just you. He’s like that to everyone, just to see how far they’ll push. Draw a line.” He sees the doubt in my face, offers an alternative. “But there are other ways to get around him. Hell, look at Steffie’s way. Be Daddy’s little girl when he’s looking, and do what you please later.” He chuckles fondly at how well Steffie gets around their dad.

It is all so simple for him. Tom is like that. People are easy for him. He meets them, he sizes them up, he knows just how to handle them. And they always like him. Instantly, the first time they meet him. And they go on liking him, always. When we were in college, all the girls had crushes on him and all the guys thought he was a helluva friend. The freaks and the bikers, the druggies and the straights, the profs and the frat guys: they’d all liked him. He shifts gears effortlessly, is never out of place. I have always envied him that talent; he is able to be anything that anyone needs, as required.

And to me, he is everything. Husband, lover, best friend. There are very few people in my life, but I have never felt alone since Tom came to me, he fills all the niches for me. I look at him and a wave of tenderness breaks over me. After all he has done for me, surely I can do this simple thing for him. Live near his family for a month, make them like me, be pleasant to them. It won’t be hard. Make Tom proud of me. In a way, it is a thing I owe them. And whenever things get hard, I’ll just remind myself that these people are Tom’s family, that without them, he wouldn’t exist.

For a moment, I flash back to the fact that without Tom, I wouldn’t exist. Not as I am now. He had taken a horribly introverted, socially hostile girl and made her over into a competent woman who was satisfied with her life. I think of our little cabin and ten acres of woods, of my job at Annie’s Organic Foods and Teas. I have friends now, real friends, something I’d never had when I was growing up. Annie and our regular customers, and Pete and Beth down the road, and Caleb our mail carrier and all the others that Tom had so effortlessly befriended for me. I’d ridden into those friendships on his coattails, learned to socialize by watching him. I should be past all these stupid doubts, should set them aside with the old scalding memories of grade school and high school and all the failed efforts of those times.

But still I hear myself say, “It’s just that the way they live and do things is so different from, well, from the way I was brought up and the way we do things. I mean, Mother Maurie’s house looks like something out of a magazine, and Steffie always looks like she’s going out to tea with Queen Elizabeth.”

Tom snorts a chuckle. “Yeah, well. I know what you mean. Sometimes it gets to me, too. But it wasn’t always like that. When Steffie and Ellie and I were kids, the money was a lot tighter. I remember plenty of hand-me-down clothes from the cousins, and lots of secondhand furniture. I remember when Mom’s end tables were wire spools with cloths over them. But in the last ten years, since the equipment dealership took off, Dad’s been able to do better for the family. And he likes that. He likes giving Mom and the girls nice things, likes living good with new furniture, and indulging Steffie and stuff. Hell, I know he can remember enough hard times for us. He’s worked damn hard to get the family where it is; don’t look down on him for liking to flash around that money isn’t so tight for them anymore. It’s a point of pride for him. But it doesn’t mean he’s going to look down on us for being broke, and having to keep things simple and cheap. He knows where that is, too.” Tom sounds a little hurt that I would find his family’s prosperity daunting.

“I know, but …” This time even I can hear the whine in my voice, and I stop a fraction of a second before Tom says, “Hush. Stop it, now. You’re just working yourself up over nothing. Relax. They’re going to love you. All you have to do is just relax and be yourself.”

“Okay,” I concede. I can hear his unspoken hope that I’ll stop chewing on my worries, and let him doze again. So I lean back in my own seat and close my eyes. I pretend to sleep.

TWO

Fairbanks, Alaska,

1963

Eleven. Betwixt and between. Two pigtails, the color of dirty straw. Fuzzy pigtails, down past my shoulders, the hair pulling free of the braid like strands breaking loose in old hemp rope. They have not been taken down, brushed, and rebraided in days, perhaps weeks. It doesn’t matter; no one scolds. My mother has six children, and her two older daughters are at a much more dangerous age than I am. They are the ones who demand all her watching. What is it to her if my hair has not been brushed and combed, the stubborn snarls jerked from my tender scalp, the long hair rebound so tightly it strains at my temples? It is summer, school is out, and we live in an aggressively rural area. There is no one to see her youngest daughter running wild as a meadow colt.

And I do. Both knees are out of my jeans, and my shirt has belonged to two older siblings before me. Boy’s shirt, girl’s shirt, only the buttons know. It lies flat down the front of my androgynous chest. There are holes in my sneakers, too, and my socks puddle around my ankles. Yes, that is me, eyes the color of copper ore, hard and green, a scatter of freckles across my nose. Unkempt, neglected child? Hardly. Free child, unwatched, unhindered, unaware of being free, as it is the only thing I have ever known. Free child in the deep heat of July, the forest baking around me in the seventy-some degrees of the Fairbanks summer sun.

I am where I should not be, but I do not even know it, nor would I care if I did. I am between the FAA tower on Davis Road and what will eventually be the Fairbanks International Airport. It is supposed to be a restricted area, but no one really cares about that. Not at this moment in time. If I want, I can follow the surveyor cuts through the forest until I’d come out to the small plane tie-downs. A bit farther, and I’d come to wide pavements of the airport, where the airplanes let people down right on the asphalt of the runways. There would be people and noise and traffic. All the things I hate. Where I am is much better. I am sitting on the bank of the slough and thinking it is the most beautiful place in the world.

The slough varies with the seasons, like a snowshoe hare varying its coat, but it is always beautiful to me. During winter it is a wide white expanse of snow, broken only by the protruding heads of the tallest grasses. The snow humps strangely over the mounds and hummocks of coarse grasses. Owls hunt over it, watching for tiny scurrying shrews and mice to break to the surface and brave the flat whiteness. If I walk cautiously, I can move across the frozen crust without breaking it, standing tall above the earth, my feet supported by millions of tiny ice crystals. Treacherous trickling sunlight sometimes softens my floor, and then I break through it and wallow up to my hips in snow that infallibly finds every opening in my clothing. That is the winter.

Then comes spring and breakup, when the slough fills with water that reflects the sky and the tangled branches of the trees on its banks and the tiny leaves budding on them. The white snow sinks down to isolated hummocks cowering in the narrow tree shadows, bleeds to death as seeping water that fills the slough. The slough flows with a perceptible current then, carrying off the melted snow to the Chena River, and birds cry above it, ravens black against the transparent blue sky. The wind of breakup reddens my cheeks, and my old socks wad down inside my battered boots. During the spring thaw, the slough is deep, how deep I do not know, for it is much too cold to think of wading in it. I jump from tuft to hummock to clump of grass to cross it, and at its highest flow I cannot cross it at all. I go home wet, my hands red-cracked claws of hands, my nose dripping, my eyes green with spring.

But that is not now. It is summer now. The early greenness has passed. There are tall yellow grasses, higher than my head, with waving tasseled heads of wild grains. The water has hidden itself beneath the living earth, only appearing in secret pools of shallow water banked with green mosses and ferns and squirming with mosquito larvae. Low-bush cranberries, tender little plants with tiny round leaves, no taller than my hand-span, coat the bank where I sit. Behind me, closer to the edge of the true forest, are twiggy blueberry bushes, bereft now of their tiny bell-like flowers, and not yet heavy with round blue fruit. Today I have seen a red fox with a spruce hen clamped in its jaws, and a litter of tiny rabbits just ventured from their burrow. I have seen the green bones of a winter-kill moose acrawl with beetly things, and pushed the bones aside to see the white grubs squirming beneath them. Myriad small creatures besides myself live and hunt here. The faun is one of them.

He is beside me, likewise lounging on the bank. He is stretched out to the lingering touch of the sun on his belly. He is totally unremarkable and completely marvelous. I love him as I love the sound of wolves at night, and stories of wild horses in thundering herds on the plains. I love him as I love my hands and my hair and my ice-green eyes. He closes the circle of who I am, and makes me complete. In loving him, I love myself. In my mind I call him Pan, but aloud I have never spoken a word to him, nor him to me. We are the closest of friends.

He has a boy’s face and arms, a boy’s curly thatch of hair atop his head, interrupted only by the nubbins of his horns, stubby things shorter than my thumbs, shiny brown like acorns. He has a boy’s chest, tanned and ribby, flat nipples like brown thumbprints. From the hips down he is neatly and unoffensively goat. His hooves are pale and cloven, slightly yellower than my toenails but much thicker. The hair on his legs is like that on any goat, smoothly brown, growing so closely it hides any trace of skin. His penis is gloved as neatly as a dog’s, held close to his lower belly in its coarsely haired sheath. The most I have ever seen of it is the pointed pink tip, moist like a puppy’s. To my eleven-year-old mind it is a superior arrangement, much better than my younger brothers’ dangling, wrinkled genitalia. More private in a way that is not prissy.

He rolls to face me, yawning, and then smiling. His teeth are white as only the teeth of young carnivores are white, and his eyes are a color that has no name. His eyes are the color of sunlight that has sifted through green birch leaves and fallen onto a carpet of last year’s leaves. Earth eyes, not brown nor green nor yellow. The color of a forest when you stand back from it.

He rises and looks at me askance, and I shrug and rise to follow him. My dog falls in at our heels. He pants delicately in the heat of the summer, making hardly a noise at all. Not for him some doggy lolling of a long pink tongue. He is more than half a wolf, my Rinky, with his sleek black coat and his pale cheeks and eyebrows. In the woods with me, he is all a wolf, and I am his cub as surely as Mowgli belonged to Akela. He has taught me everything, this dog, that a young creature must know to stay alive in the forest. From him I have learned to be still and to be silent, and to move with the forest instead of through or against it. I have watched him and seen how well he fills the niche that nature has allotted to him. I, too, will be as he is, perfect in my place.

We follow Pan, Rinky and I, and he leads us down the slough. We walk in the flat troughs that meander between the hummocks of grass. Short weeks ago, water flowed where our feet walk now. We flow as it did, silent and seeking our level. Pan has neither hips nor buttocks, but only the sleek flanks of an animal and the restless tail of the deer kind. His cloven hooves leave more of a mark than Rinky’s wolf feet, and my sneakers leave the least discernible track of all. Insects chirr around us, and the air is heavy with pollen and sleep. I can believe that, save for us, nothing larger than a shrew is stirring in the forest at this hour.

Then the duck explodes in front of me, right before my feet, her brown pinions slashing my face as she rises on her battering wings. Her nerve has been shattered; she withstood the passing of Pan and Rinky so close to her nest, but I, a human, am too totally foreign to her experience. I fall back with an incoherent cry, my hands rising to protect my face, but she is already gone. My eyes tear from the slapping they have taken, but that is the sole extent of their damage. When I lower my hands and blink my eyes clear of tears, they are laughing at me.

Rinky’s pink tongue does loll now, mockingly, dangling over his picket fence of white teeth and his smooth black doggy lips. Pan is worse. He clutches his belly, bends over it, brown curls falling into his eyes as he shakes with silent hilarity. His teeth are very white, his mouth is wide with mirth. Miffed, I ignore both of them, and crouch to examine the nest.

The nest is a late one, probably the duck’s second effort this year. To the casual eye, it is empty. But with thumb and forefinger I lift the soft blanket of down that covers the fourteen pale turquoise eggs. The eggs are not much larger than grade-AA chicken eggs from the store, but they are much more real. Eggs from the store are cold and bony white, their surfaces dry and chalky, trapped in cardboardy trays. These eggs are warm, and smooth, almost waxy to the touch. I take two and Pan takes one, and we carry them off with us, leaving the duck free to return to her brooding.

We go back to the sunny bank of the dried-up slough and sit on the moss and eat our eggs. Pan and I bite the ends off ours and spit the crumpled bits of shell aside before we suck out the warm white and the sudden glop of the yolk. Rinky puts his between his front paws and delicately breaks it with his teeth so that he can lap up the egg and eat the shell that held it.

And that is all that there is to this day, but it needs nothing more. It is complete, like the scene trapped inside a glass paperweight, a whole sufficient to itself. I am eleven and lying there between a dog and a faun. We three make a circle, from human to beast and back again. I love them as I love my hands or my hair, unthinking, totally accepting. They are the two most important creatures in my life and always will be. When we grow up, I will be Pan’s mate and we will live and hunt in these woods and Rinky will always run beside us. I know these things as well as I know that the summer sky is blue and permafrost is cold.