Kitabı oku: «Valley of the Moon», sayfa 2

Martha, who rarely showed her affection for me in public, picked up my hand and threaded her fingers through mine. It was not a romantic gesture. It did not make me feel like we were husband and wife. Instead it stripped me of my years and made me feel as if we were two orphan children wandering through a vast forest.

You might think our behavior odd. Why weren’t we rejoicing? Clearly we’d been spared. But I was a realist, as was Martha.

Something was very wrong.

Everybody was present and accounted for, and there wasn’t so much as a single scratch or a scraped knee. If there were wounds, they were not the visible sort.

The only thing that was different was the towering bank of fog that hung at the edge of the woods.

“Glen Ellen,” Magnusson reminded us.

“Yes,” said Martha. “Of course, our friends in Glen Ellen.” She clapped her hands together and shouted out to the crowd. “We can’t assume they’ve been as fortunate as us. We must go to them.”

I stopped a moment to admire my spitfire of a wife. Barely five feet tall, maybe ninety pounds. Butter-yellow hair, which was loose around her shoulders, as the earthquake had interrupted her in mid-sleep. Martha was not a woman who traded on her beauty. It shone through, even though she eschewed lipstick and rouge and wore the plainest of serge skirts. I felt a sharp prick of pride.

It took us nearly an hour to organize a group of men and a wagon full of supplies.

“Be careful,” said Martha nervously as I climbed up on my horse. “There could be more aftershocks.”

“The worst is over,” I said. “I’m sure of it.”

“I don’t like the look of that fog,” she said. “It’s so thick.”

It was a tule fog, the densest of the many Northern California fogs. When a tule fog descended upon Greengage, spirits plummeted, for it heralded day after day of unremitting mist and drizzle. But these fogs were vital to the vineyard as well as the fruit and nut trees. Without them the trees didn’t go into the period of dormancy that was needed to ensure a good crop.

“I know the way to Glen Ellen. I could get there blindfolded.” I smiled brightly in order to allay her fears. “We’ll be back before you know it.”

Within seconds of entering the fogbank, I fell off my horse, gasping for air. Disoriented, confused, my chest pounding. A profound, fatal breathlessness.

The two men who had gone before me were already dead.

I was lucky. Magnusson pulled me out before I succumbed to the same fate. Friar, our doctor, came running. He later told me that when he felt my pulse, my heart was beating almost four hundred times a minute. Another few seconds in the fog, and I would have died, too.

In my experience, when the unthinkable happens, people respond in one of two ways: they either become hysterical or are paralyzed. Greengage’s reaction was split down the middle. Some panicked and screams of anguish filled the air; others were mute with shock. Only a minute ago we’d ridden into the fog, as we’d done hundreds of times before. And now, a minute later, two of our men, husbands and fathers both, were dead. How could this be?

I preferred the wails; the silence was smothering. People covered their mouths with their hands, looking to me for answers. I had none. I was as shocked and horrified as anybody else. The only thing I could tell them was that this was no ordinary tule fog.

We put our questions on hold as we tended to our dead. The two men had been stalwart members of our community, with me since the beginning. A dairyman and a builder of stone walls.

Magnusson tossed a spadeful of dirt over his shoulder.

“Let me help,” I said to him, feeling a frantic need to do something.

“No. You are not well.”

“Give the shovel to me, I’m fine,” I insisted.

Nardo, Matteo’s sixteen-year-old son, took the shovel from Magnusson. “You’re not fine,” he told me. “You’re the color of a hard-boiled egg.”

He was right. Whatever had happened in the fog had left me utterly exhausted, and my rib cage ached. It hurt to breathe.

“Thank you,” I said.

The boy bent to his grim task. Digging the graves.

That afternoon, time sped by. It careened and galloped. The men were buried one after the other. People stood and spoke in their honor. People sank to their knees and wept. Grief rolled in, sudden and high, like a tide.

Then it was evening.

I lay in bed unable to sleep. I felt hollow, my insides scraped out. I sought refuge in my mind. I turned the question of this mysterious fog over and over again. Maybe we were mistaken—perhaps the fog was not a fog, it was something else. Had the massive temblor released some sort of a toxic natural gas that came deep from the belly of the earth? If it was a gas, it would dissipate. The wind would eventually carry it away. By tomorrow morning, hopefully.

During breakfast in the dining hall, I relayed my theory. The gas was still there, as dense as it had been yesterday, though it didn’t appear to be spreading. There was a little niggling thought in the back of my mind. If it was a gas, wouldn’t it also emit some sort of a chemical, sulfurous odor?

I divided us into groups. One group set off to investigate the wall of gas further. Where did it start? Where did it end? Probably it didn’t encircle all of Greengage, but if it did, were there places where it wasn’t as dense? Places where somebody fleet of foot might be able to dart through without suffering its ill effects?

Another group conducted experiments. The gas had to be tested. Was there any living thing that could pass through it? The children helped with this task. They put ants in matchboxes. Frogs in cigar boxes. They secured the boxes to pull-toys, wagons, and hoops. They attached ropes to the toys and sent them wheeling into the gas.

The ants died. The frogs died. We sent in a chicken, a pig, and a sheep. They all died, too. The wall encircled the entirety of Greengage, all one hundred acres of it, every square foot of it as dense as the next. Whatever it was made of, it did not lift. Not the next morning. Or the morning after that.

The first week was the week of unremitting questioning. Wild swings of emotion. Seesawing. The giving of hope, the taking of hope.

Was it a gas? Was it a fog? Why had this happened? What was happening on the other side of it? Were people looking for us? Surely there’d be a search party. Surely somebody was trying to figure out how to get through the fog and come to our aid.

The second week was the week of anger. Bitter arguments and grief.

Why had this happened to us? What had we done to deserve this? Were we being punished? Why hadn’t any rescuers arrived yet? Why was it taking so long?

People grew desperate.

Late one night, when everybody was asleep, Dominic Salvatore tiptoed into the fog, hoping if he moved slowly enough, he would somehow make it through. He got just five feet before collapsing.

We lost an entire family not two days later. Just before dawn, they hitched their fastest horse to their buckboard, hid under blankets, and tried to race their way through the fogbank. The baker was the only one awake at that hour. The only one who heard the sound of their wagon crashing into a tree. The horse’s terrified whinny. The cries of the children. And then, silence.

After that, nobody tried to escape again.

The third week, the truth of our situation slowly set in. Meals at the dining hall were silent. Appetites low. Food was pushed away after one or two bites. Everybody did their jobs. What else could we do? Work was our religion, but it also produced our sustenance. It gave us purpose. It was the only thing that could save us. The cows were milked. Fields plowed. Everybody thought the same thing but nobody would voice it. Not yet, anyway.

Help wasn’t coming. We were on our own.

LUX

San Francisco, California 1975

I sat in the passenger seat holding a squirmy Benno on my lap. He had a ring of orange Hi-C around his mouth. I’d have to scrub it off before he got on the plane; it made him look like a street urchin. He sucked on the ear of his stuffed Snoopy while his sticky hand worked the radio dial.

He spun past “Bennie and the Jets” and “Kung Fu Fighting.”

“But you love ‘Kung Fu Fighting,’” I said.

He vehemently shook his head and Rhonda laughed, her Afro bobbing. An X-ray technician at Kaiser, she’d left work early to drive us to the airport and help me see Benno off. We’d been roommates for the past three years, and she was the closest thing I had to family in California. Right now she seemed to be the only person in my life who wasn’t keeping a constant tally of my failures (perennially late everywhere I went, maxed-out credit cards, beans and toast for dinner three times a week, musty towels, and an ant infestation in my closet due to the fact that Benno had left half an uneaten hot dog in there that I didn’t discover for days).

Benno stopped turning the dial when he heard whistling and drumming, the opening instrumentals for “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero.” He nestled back into my chest. Within a minute, his eyes were welling up as the soldiers were trapped on a hillside. He moaned.

“Change the station,” said Rhonda.

“No!” shouted Benno. “The best part’s coming. The sergeant needs a volunteer to ride out.” Tears streamed down his face as he sang along.

“God help us,” I mouthed to Rhonda.

“Babe, is this a good cry or a bad cry?” I whispered to Benno.

“G-good,” he stuttered.

“Okay.” I wrapped my arms around him and let him do his thing.

Benno loved to feel sad, as long as it wasn’t a get-a-shot-at-the-doctor kind of sad. He loved, in fact, to feel. Anything. Everything. But this kind of emotion, happy-sad, as he called it, was his favorite flavor. Tonight I would indulge him. We wouldn’t see each other for two weeks.

Rhonda took one last drag of her cigarette and flicked the butt out the window. She was no stranger to this kind of melodrama. The song ended and Benno turned around, fastened himself to my chest like a monkey, and buried his head in my armpit.

I stroked his back until he stopped trembling. He looked up at me with a tear-streaked face.

“Better?” I asked.

He nodded and ran his finger across the faint blond down on my upper lip. He made a chirping sound. My mustache reminded him of a baby chick, he’d once told me. I told him you should never refer to a lady’s down as a mustache.

I’d given Benno my mother’s maiden name—Bennett. I loved the clean, bellish sound of it. She’d flown out for his birth; my father had not. At that point he and I had been estranged for more than two years, and my choice to have a son “out of wedlock” was not going to remedy that situation.

My mother, Miriam, had been campaigning for Benno to come east for a visit for months. I’d said no originally. The thought of shipping Benno across the country to my hometown of Newport, Rhode Island, land of whale belts, Vanderbilt mansions, and men in pink Bermuda shorts, was unthinkable.

“Please,” she said. “He needs to know where he comes from.”

“He comes from San Francisco.”

“He barely knows me.”

“You visit three times a year.”

“That’s not nearly enough.”

She upped the ante. She promised to pay for everything. The airfare, the escort who would accompany him on the plane. Finally I relented.

I’d met Nelson King, Benno’s father, in a bar a week before he shipped out to Vietnam.

“You’re not from here” was the first thing he said to me.

I’d been in San Francisco a little over a year at that point and thought I was doing a pretty good job of passing as a native. I’d worked hard to shed my New England accent. I’d traded in my preppy clothes for Haight-Ashbury garb. The night we met, I was wearing a midriff-baring crocheted halter top with white bell-bottom pants.

“What makes you say that?” I asked.

“You hold yourself differently than everybody else.”

“What do you mean? Hold myself how?”

He shrugged. “Stiffer. More erect.”

I puffed out my cheeks in irritation. He was an undeniably good-looking man. Pillowy raspberry lips. Luminous topaz skin. He could be anything. Persian. Egyptian. Spanish. Later I’d learn his mother was black, his father Puerto Rican.

“That wasn’t an insult,” he said. “That was a compliment. You hold yourself like somebody who knows their worth.”

I was nineteen, in between waitressing jobs, and desperately searching for an identity. That he saw this glimmer of pride in me was a tiny miracle. We spent every day together until he shipped out. It wasn’t love, but it might have blossomed into that if we’d had more time together.

After he’d left, I’d written him a few letters. He’d written back to me as well, echoing my light tone, but then we’d trailed off. Three months later, when I’d found out I was pregnant, I’d written to him again, but didn’t get a reply. Soon after, I discovered his name on a fatal casualty list in the San Francisco Examiner.

Although his death was tragic and shocking, the cavalier nature of our relationship and that it had resulted in an unexpected pregnancy was just as jarring. We’d essentially had a fling, a last hurrah that had allowed for a sort of supercharged intimacy between us. A quick stripping down of emotions that I imagined was not unlike the relationship he might have had with his fellow soldiers. The details of our lives didn’t matter and so we’d exchanged very little of them. We’d just let the moment carry us—to bars, to restaurants, and to bed.

In an instant, the dozens of possible futures I’d entertained for myself receded and the one future I’d never considered rolled in.

I was pregnant, unmarried, and alone.

“What do I call the man?” asked Benno as Rhonda pulled into the airport parking garage.

“What man?”

“The man who lives with Grandma.”

“The man who lives with Grandma will be away when you visit,” I said.

The man who lived with Grandma, a.k.a. my father, George Lysander, would be spending the last two weeks of August at his cabin in New Hampshire, as he’d done for the last forty-something years. My mother had timed Benno’s visit accordingly.

“I met him before,” said Benno.

“You were only two, Benno. Do you really remember meeting him?”

“I remember,” he insisted.

My father had been in San Francisco for the Association of Independent Schools’ annual conference (he was dean of admissions at St. Paul’s School in Newport). He’d arranged to stop by our apartment for dinner: it would be the first time he’d met his grandson.

“For you,” he’d said to Benno, handing him a loaf of sourdough bread.

Benno peeked out from behind me, his thumb in his mouth.

“Say thank you to your grandfather,” I prompted him.

“He doesn’t have to thank me,” said my father.

“Yuck crunchy bread,” said Benno.

I watched my father taking Benno in. His tea-colored skin. His glittering, light brown eyes.

“I don’t like it either,” my father said. “How about we have your mother cut off the crusts?”

Benno nodded.

“We can make bread balls.”

It was an offering to me. Bread balls were something my father and I did together when I was a little girl. Plucked the white part of the bread out of the loaf and rolled tiny little balls that we dipped in butter and salt and then popped into our mouths. It drove my mother crazy.

That was all it took. Benno adored my father. He climbed into his lap after dinner and made him read The Snowy Day three times. I washed the dishes and fought back tears of relief and resentment. Why had it taken him so long to come around?

But he hadn’t—not really. When Benno was standing in front of him in the same room, he came around. But when he was three thousand miles away from us, back home in Newport, the distance grew again. His contact with Benno dwindled to a once-a-year birthday card. The incongruity between our realities, the life I’d chosen and the life he’d wanted for me, was too great to reconcile.

“What if he’s there?” asked Benno.

“He won’t be.”

“But what if he is? What do I call him?”

“Then you call him Grandpa,” I said. “Or Grandfather. Or Mr. Lysander. Or George. Christ, Benno, I don’t know. You’ll have to ask him what he wants to be called, but I don’t think it’ll be an issue. You won’t see him.”

My father had never missed his precious two weeks at the lake. He would not be missing them now.

I hated airports. They were liminal space. You floated around in them untethered between arrivals and departures. A certain slackness always descended upon me as soon as I walked through the airport doors.

“Are you scared?” I asked Benno.

“There’s nothing to be scared of, kid,” said Rhonda. “You’re going on an adventure.”

“I’m not scared,” he said.

“Look, babe. The days will be easy. It’s the nighttime that might be hard. That’s when you’ll probably feel homesick. But just make sure you—”

“Can we go up the escalator?” he interrupted me.

I stopped and crouched down. “Benno, do you need a hug?”

He blew a tiny spit bubble. “No, thank you.”

“Don’t do that, that’s gross.”

He sucked it in.

“Well, may I please have a hug?” I asked.

“I’m busy.”

“You’re busy? Busy doing what?”

“Leaving, Mama,” he sighed.

Abortion wouldn’t be legal in California for another three years, but even if it were, I never would have terminated the pregnancy. Perhaps given different circumstances I’d have chosen differently, but for this baby my choice was life. Of course I didn’t know he’d turn into Benno. My Benno. I just knew he needed to come into the world.

Everybody thought I was crazy. Not only was there no father in the picture, but the father was black. How much harder could I make it for myself—a single white mother with a mixed-race child?

He brought me such joy. I never knew I was capable of loving somebody the way I loved him. Purely, ragged-heartedly. I couldn’t imagine my life without him in it.

But my life with him in it was also ridiculously hard. I was a parent twenty-four hours a day. Every tantrum, every cry of hunger, every question was mine to soothe, to feed, and to answer. I had no spouse to hand him off to. No partner to help pay the bills. I could never just walk away. I was the sole person in charge of resolving every issue in my child’s life, from how to deal with bullies, to Is that rash serious? to He’s three years old and still not using a spoon properly—what’s wrong with him?

I wasn’t stupid. I’d known that raising a child on my own would be challenging. It was the isolation that blindsided me. The intractable, relentless truth was that I was alone. I could meet other mothers on the playground. We could talk bottle-feeding and solid foods, how to get rid of cradle cap, the best remedy for diaper rash. We could laugh, commiserate, watch each other’s babies while somebody ran to the bathroom. But at the end of the day, they went home to their husbands and I went home to an apartment that was dark until I turned on the lights.

When we got to the gate, I was panicked but doing my best to hide it. I’d never been separated from Benno for more than a night.

“You must be Benno,” said the stewardess when we checked in. “We’ve been waiting for you!” She picked up the phone, punched three numbers, and spoke softly into it. “Jill, Benno Lysander is here.” She hung up. “You are going to adore Jill. She’s a retired stewardess. She’s got all sorts of activities planned for you, young man. Crossword puzzles. Hangman. Coloring books. A trip to the cockpit to meet the captain, and if you’re very good, maybe you’ll get a pair of captain’s wings.”

Benno’s eyes gleamed. I was on the verge of tears.

“Stop it,” Rhonda whispered. “He’s happy. Don’t screw this up.” She pulled her camera out of her pocketbook. “Let’s get a Polaroid of the two of you before you go.”

Five minutes later Benno was gone.

We walked out of the airport silently. Rhonda waved the Polaroid back and forth, drying it. When we got to the car, she handed me the photo.

I’d forgotten to wash Benno’s face. His mouth was still rimmed with orange.

Later, back at our apartment, Rhonda poured me a shot of Jack. Then she looked at my face and poured me a double. “It’s only two weeks,” she said.

I pounded the whiskey in one swallow. “What was I thinking? He’s a baby.”

“He’s an old soul. He’s a forty-year-old in a five-year-old body. He’ll be fine. Give me that glass.”

I slid it across the table and she poured herself a splash.

“I forbid you to go in his room and sniff his clothes,” she said.

“I would never do that,” I said.

“Hmm.” She took a dainty sip of the whiskey.

Elegant was the word that best described Rhonda Washington. Long-necked, long-legged. An Oakland native, Rhonda had five siblings. All of them had R names: Rhonda, Rita, Raelee, Richie, Russell, and Rodney. Rhonda’s mother said it was easier that way. All she had to do was stick her head out the window and yell “Ruh” and all the kids would come running.

“Now, what’s your plan? You aren’t just going to sit around the house moping,” she said.

“I’ve got this week off, then I’m working double shifts all next week.” I waitressed at Seven Hills, an Irish pub in North Beach.

“So what are you going to do this week?”

“I’m going camping.”

“Camping?” said Rhonda. “Like, car camping? With a bathroom and showers?”

“No, middle-of-nowhere camping, with a flashlight and beef jerky.”

I’d given a lot of thought as to how I was going to spend my first week of freedom in five years. I let myself fantasize. What if I could do whatever I wanted, no matter the cost? Where would I go? How about Paris? No, too snooty. Australia, then; Aussies were supposed to be friendly. Oh, but I’d always dreamed of seeing the Great Wall. And what about the Greek islands? Stonehenge? The Taj Mahal? Pompeii? I pored through old National Geographics—I rarely let myself dream anymore. My list quickly grew to over fifty places.

In the end I decided on camping right near home. Yes, it was all I could afford, but I wasn’t settling; before I’d had Benno it had been my escape of choice. I’d been to Yosemite, Big Sur, and Carmel. Closer to home, I’d camped on Mount Tam, at Point Reyes, and in the Marin Headlands. If I was depressed, angry, or worried, I headed for the hills. If I didn’t get a regular dose of nature (a walk in Golden Gate Park didn’t count), I wasn’t right. I needed to get away from the city. Sit by myself under a tree for hours. Fall asleep to the sounds of an owl hooting rather than the heavy footfalls of my upstairs neighbors. I was competent in the wilderness. Nothing frightened me. I wanted to feel that part of myself again.

Rhonda tossed her head. “Okay, nature girl.”

“What? I am a nature girl.”

“Using Herbal Essence does not make you a nature girl, Lux. When’s the last time you went camping?”

“A few months before Benno was born.”

“Do you still remember how?”

“You don’t forget how to sleep in a tent, Rhonda.”

“This just seems impulsive. Is it safe to go alone?”

“Yes, Rhonda, it is. I can take care of myself. I know how to do this.” My father was an Eagle Scout. He taught me everything he knew.

“Fine. Why don’t we make a list of what you’ll need.”

“I already have a list.”

I knew what Rhonda was thinking. Here goes Lux again, just throwing things together and hoping for the best. That was how I lived my daily life, from hour to hour, paycheck to paycheck. This was the only Lux she knew. I wanted to show her another side of me.

“I’ve been planning this for months, you know,” I said.

“Really?”

“Really.”

“Well—good,” she said. “Good for you.”

I walked around the table and threw my arms around her. “Admit it. You love me.”

“No.”

“Yes. You love me. Silly, flighty me.”

Rhonda tried to squirm out of my grasp, but she grinned. “Don’t ask me to come rescue you if you get lost.”

“I won’t.”

“And don’t take my peanut butter. Buy your own.”

“Okay.”

I’d already packed her peanut butter.

I did go into Benno’s room at midnight. I did lie down on his bed and bury my face in his pillow and inhale his sweet boy scent. I fell asleep in five minutes.

Rose Bennedeti and Doro Balakian were my landlords, the owners of 428 Elizabeth Street, a shabby (“in need of some attention but a grand old lady,” said the ad I’d answered in the classifieds) four-unit Victorian in Noe Valley. A lesbian couple in their seventies, they occupied the top-floor flat. We lived on the second floor, the Patel family (Raj, Sunite, and their daughter, Anjuli) lived on the first, and Tommy Catsos, a middle-aged bookstore clerk, lived in the basement.

I loved Rose and Doro. Every Saturday morning, I’d go to the Golden Gate Bakery to get a treat for them. When I rang their bell, the telltale white box in my hands, Rose would open the door and feign surprise.

“Oh, Lux,” she’d say, hand over her heart. “A mooncake?”

“And a Chinese egg tart,” I’d answer.

“Just what I was in the mood for! How did you know?”

This Saturday was no different, except for the fact that the two women wore glaringly white Adidas sneakers and were dressed in primary colors, like kindergartners. They were in their protesting clothes.

“We’re going to City Hall. Harvey’s”—Doro meant the activist Harvey Milk; they were on a first-name basis with him—“holding a rally, and then there’s to be some sort of a parade down Van Ness. Come with us, Lux.”

“We shall be out all day, I would think,” said Rose.

Rose and Doro were highly political, tolerant, extremely smart (Doro had been a chemist, Rose an engineer), and believers in everything: abortion rights, interracial marriage, and the ERA. Why not? was their creed.

“You’ll join us, of course,” said Doro.

I frequently gave up my weekends to march, picket, or protest, dragging Benno along with me. I believed in everything, too.

I put the bakery box on the counter. “I can’t. I’m going on a camping trip.”

“Oh, how wonderful!” said Doro. “Good for you, Lux. A Waldenesque sojourn into nature.”

“Would you like to bring a little …?” asked Rose. She put her thumb and index finger to her mouth and mimed inhaling.

“You smoke?”

“No, dear, we don’t partake, but we like to have it for our guests. Shall I get some for you?”

I wasn’t a big pot smoker.

“Just one joint,” said Doro. “You never know.”

Only in San Francisco would an old woman be pushing pot instead of a cookie and a nice cup of tea on you.

“All right,” I agreed.

“Marvelous!” they both chimed, as if I’d told them they’d just won the lottery.

I’d purchased five Snoopy cards from the Hallmark store to send to Benno in Newport. I didn’t want to overwhelm him or make him homesick. I just wanted him to know I was there. Filling them out was a surprisingly difficult task. I was going for breezy, with an undertone of Mommy loves you so much but she did not sleep in your bed last night. Here’s what I came up with:

Benno, I hope you had a great day!

Benno, Hope you’re having a great day!

Benno, I’m sure you’re having a great day!

Benno, Great day here, I hope it was a great day there, too.

Benno, Great day? Mine was!

I asked Rhonda to mail a card each great day I was gone.

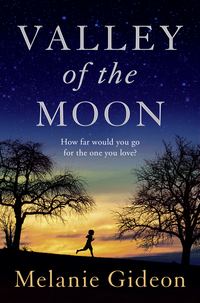

I wanted to camp somewhere I hadn’t been before. I chose Sonoma, about forty miles from San Francisco. Wine country. Also referred to as the Valley of the Moon. When I read about it in my guidebook, I knew this was where I would go. Who could resist a place called Valley of the Moon? It was an incantation. A clarion call. Just saying it gave me goosebumps.

It was the Miwok and Pomo tribes who came up with the name Sonoma. There was some dispute as to whether it meant “valley of the moon” or “many moons” (some people claimed the moon seemed to rise there several times in one night), but that wasn’t important. What was important was that the Valley of the Moon was supposed to be enchanting: rushing creeks and madrones, old orchards and wildflowers. The perfect place to lose myself. Or find myself. If I was lucky, a little of both.

By the time I’d finished packing, it was just after noon and 428 Elizabeth Street was empty. Rose and Doro were still at the rally, Tommy was working, Rhonda had taken the bus across the bay to visit with her family, and the Patels had gone off for a picnic in the park. I threw my pack in the trunk of my car and hit the road.

An hour and a half later, I pulled into the parking lot of Jack London State Park.

I relied on instinct out in the woods; I depended on my gut. I could have made camp in a few places, but none of them was just right. Finally I found the perfect spot.

The scent of laurel and bay leaves led me to a creek. I trekked up the bank to a small redwood grove. Sweat dripped between my shoulder blades. I was in my element; I could have gone another ten miles if needed. I dropped my pack. Yes, this was it. The air smelled of pine needles and cedar. The clearing felt holy, like a cathedral. I punched my arms in the air and hooted.

I experienced the absence of Benno (not having to hold him as a fact in my mind every minute) as a continual dissonance. I had to remind myself: He’s not here. He’s okay. He’s with Mom. I hoped the shock would lessen as the days went on and that I’d not only acclimate to the solitude, but relish it. Nobody needed me. Nobody was judging me. I could do or act or feel however I wanted.