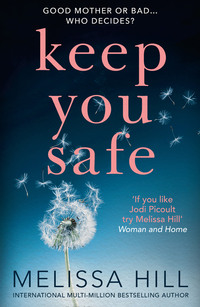

Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Keep You Safe», sayfa 4

This was a scenario that Madeleine and Tom hadn’t run the odds on.

Realising that she had left Lucy in silence on the line, she whispered, ‘And Ellie Madden too?’ Christ, had she passed it on to the entire Junior Infants class, the whole school even? Oh God…

‘No, apparently Ellie actually does have chicken pox – that’s already confirmed. But, Maddie, get Clara to a doctor straight away. And you have to get Jake out of school too, once it’s in your house, he’s likely still infectious, even though…’ To her credit, Madeleine was grateful to Lucy for not making a big deal of their refusal to vaccinate. Goodness knows she and Tom had faced considerable ire from various quarters before about it.

‘I talked to the principal at Applewood,’ her friend went on. ‘Kate made them aware right away, and they’re hoping to keep this quiet for the moment. It’s a good thing it’s nearly the weekend as they don’t want a full-blown panic, but they need to identify who is the highest risk – anyone with autoimmune issues or anything like that. There are very few others there who aren’t already immunised, thank goodness, but…’

Lucy’s voice trailed off and right then Madeleine felt deeply ashamed that her family – her choice – had visited this on the school.

‘You know, kids that aren’t protected can still be helped, Madeleine. I looked it up and if you do vaccinate within seventy-two hours of a suspected outbreak, infection can still be prevented. So I just thought that maybe it’s not too late for Clara…’

Despite herself, she felt defensive. ‘Lucy, I’m sorry but I can’t talk about it now,’ she said wearily. ‘That’s between me and Tom. It’s a family decision.’

And she knew exactly what her husband would have to say on the matter. No way.

‘Sorry, Maddie,’ Lucy replied quietly. ‘I just thought… sorry.’

Madeleine took a deep breath. She knew her friend was only trying to help. ‘No need to apologise. It’s just a shock… and I’m trying to get a grip on what I should do.’ In truth, she was still a bit floored that this had happened, but at the same time she needed to get her ass in gear… she’d have to call Tom at work and the GP of course, as well as haul Jake out of school and a million other things…

A cold shiver ran its way up Madeleine’s spine as she looked back at her feverish daughter and suddenly a new realisation set in – one that carried with it a whole new level of worry. Measles… Clara really was ill too – a lot more feverish and uncomfortable than Jake had been.

Maybe it would be more serious this time.

The odds were small, but they were still odds: measles could be fatal.

For all these years, she and Tom had played them, and now that horrible realisation, albeit distant and buried, rose once again to the fore.

Oh God… what have we done…

Madeleine swallowed hard, and her thoughts instantly turned to Kate O’Hara, who was in the same situation as her at that moment. Well, almost the same. After all she had Tom to share the burden, whereas poor Kate was on her own.

‘Is Rosie OK?’ she asked, trembling. ‘Should I call her mother?’

Lucy was circumspect. ‘I’m not sure that’s the best idea just at the minute. Like you, she has a lot on her plate now. Maybe you should just focus on Clara for the moment,’ her friend advised.

Madeleine nodded. In truth, the idea of talking to Kate just then was horrifying, especially if she too suspected Clara was the carrier.

Lucy was probably right and she knew Kate much better than Madeleine did. In fairness, she hardly knew Rosie’s mum at all, having only minimal contact with her at the school or related activities, and of course that time when the poor thing lost her husband.

But, more to the point, what could Madeleine possibly do for Kate’s daughter now other than apologise?

Deciding she’d spent more than enough time wallowing, she said goodbye to Lucy before springing into action and trying to get a handle on this thing.

First, she called Tom’s work, but, failing to rouse him anywhere in the building, Ruth his secretary promised she’d get him to call his wife straight back. No response from his mobile either, so Madeleine immediately phoned their GP’s surgery, quickly outlining the situation to the receptionist.

‘Measles? Are you sure, Madeleine?’ Rachel Kennedy, another mother with a much older child at Applewood asked. ‘Isn’t Clara immunised against that?’

Swallowing her mortification, she explained to Rachel that no, neither of her children had received the MMR jab.

‘I… I had… no idea. I’ll have to get Dr Barrett to call you back about a house call then.’ Rachel’s disapproval was so thick Madeleine could actually feel it down the line. Her voice dripped with scorn. ‘Obviously you can’t bring a highly contagious child to the surgery.’

Obviously.

‘I understand that. Thanks, Rachel.’

After hanging up the phone, Madeleine moved once again to her daughter’s bedside and choked back a sob at Clara’s now undeniably rash-ridden feverish body; the full implications of her and Tom’s decision now well and truly coming home to roost.

Chapter 7

I felt ready to tear out my hair as I paced the floor at Glencree Clinic. My personal and professional lives had once again merged in the worst way.

Yet I hadn’t worked, at least here, for days.

I’d spent the weekend at home with Rosie when I was more certain of my diagnosis and she displayed all of the classic measles symptoms. Of course, I had consulted with a GP too, but ultimately for measles – much like chicken pox – you had to let it run its course. It’s a virus and can’t be treated with antibiotics.

On Friday morning when I called in to work and stayed at home with Rosie, I worked to control her fever, tried to keep her comfortable, all the while wondering how on earth this had happened, and hoping against hope that my tough cookie survivor would have the strength to battle it out.

This was the outcome Greg and I most worried about back when her allergy was first diagnosed and we had to make a call on the MMR vaccine.

‘If she catches something, we’ll just have to deal with it,’ my husband advised, typically implacable. ‘It’s unlikely though – herd immunity for measles is very high in this country. And anyway what choice do we have?’

None whatsoever I knew, realising now that Greg’s faith in so-called herd immunity had clearly been misplaced. Measles might be rare these days, but it was still possible.

And for my poor Rosie just now, terrifyingly real.

At least I knew my own chances of getting sick were slim. As a healthcare professional I was vaccinated as a matter of course against most standard infectious diseases. Still, as any parent knows, those first few hours dealing with a coughing child and a germ-filled house is enough to drive you crazy.

But I’d thought we were getting through it OK – or rather Rosie was – until tonight.

Lucy had come over earlier in the evening to help me out and confirmed that yes, little Clara Cooper had indeed also gone down with it, but according to Madeleine seemed to have improved over the weekend.

I started to think positive; maybe Rosie was close to being out of the woods too? But then, almost out of nowhere, her early fever returned. And spiked. Seriously spiked, over 104 degrees. Almost in tandem, my heart dropped the other direction.

I knew the danger zone all too well and my daughter was in it.

Lucy and I hustled to get her undressed and into a cold bath, but still, we couldn’t get her fever down. I’ve dealt with a lot of stressful medical situations, but it’s completely different when it’s your child, your own flesh and blood.

While I was trying my damnedest not to panic, in truth I was very scared. But even though I was scared, I’m not an idiot. And when Rosie had a febrile seizure, right there in the bath, I knew that this was very serious. Fighting the infection was consuming her and I needed to get her to hospital – fast.

Unlike the good hour it would take to reach one of the Dublin hospitals, Glencree was only fifteen minutes down the road, and my workplace was well enough equipped for paediatric emergencies. Notwithstanding the fact that I implicitly trusted my colleagues to do their best for my little girl.

Lucy and I got Rosie wrapped up and into the car, but the poor thing was in a bad way, shivering and burning up at the same time. I swallowed the lump in my throat, trying to remain strong, hoping and praying that it was just one seizure and that it wouldn’t happen again.

But then it did – right as we were flying down the road in Lucy’s Jeep, only minutes away from my workplace. I held on to my daughter in the back seat – to hell with the seat belt – trying to get her to turn on her side safely so she wouldn’t choke on her own tongue.

All the while screaming inside and praying to God not to do this to me again.

Please don’t take my daughter away too…

When Lucy squealed to a stop in front of the clinic’s entrance, I had to do everything in my power not to jump out of the car and start screaming for assistance. Thankfully, Lucy had no compunction about doing just that on my behalf.

Minutes later, my still-thrashing daughter was strapped to a stretcher and hustled indoors. I recognised several of the staff and nurses and knew one or two of the paramedics on shift, at least by name.

They would help Rosie, I reassured myself. They had the equipment and resources to control her fever – much more so than what I could do at home. I allowed myself to feel just the tiniest bit of relief and reminded myself that while febrile seizures were scary, they were mostly harmless; a natural result of the body’s high temperature when fighting illness. On a practical level, I knew all this but it still didn’t make it any less scary.

Rosie was in good hands in Glencree, it was the best place for her just then. I had to trust the very talented people around me. I had no choice.

A little later, they were indeed able to stabilise her and bring her temperature down just a little.

I literally pounced on Dr Jackson, the on-call paediatrician who just then was coming my way. I knew her a little, but personal decorum goes out the window when you’re frantic for your child.

‘How is she? Will she be OK?’ I babbled, my heart in my mouth at the sight of the doctor’s worryingly expressionless face.

‘Kate…’ she began, using that tone, one I’d heard uttered by hospital staff countless times (hell, I’d used it myself) when bracing themselves to give people news that wasn’t good.

Oh God…Terrified, I waited for the doctor’s next words to come out of her mouth, bracing myself for the worst.

‘It’s looking like Rosie has pneumonia,’ Dr Jackson told me gravely, and I gasped with horror.

Pneumonia…

My God, how had I missed it? I should have had my little girl seen to long before now… what kind of idiot was I? I was supposed to be an RN for goodness’ sake… I had a goddamn Masters degree and still I didn’t realise my own child had pneumonia…

The doctor put a gentle hand on my arm. ‘As a precaution, probably best if we transfer her to Dublin where they can keep an eye on her,’ she said, referring to the national children’s hospital in the city. We’ve given her antibiotics and are now trying to get her hydrated and in better shape for the ambulance journey, but it’s going to take a little time.’ She smiled gently. ‘Kate, I know what you’re thinking and, please, try not to be too hard on yourself – sometimes it’s hard to tell with these things…’

‘I just can’t believe I didn’t even consider it…’ Especially when pneumonia was one of the most common complications with measles. I burst into tears, and allowed Lucy to lead me to a nearby chair, whereupon she let me cry on her shoulder exhausting myself even further.

Dr Jackson lightly patted my shoulder, and advised that I would be able to reunite with Rosie when they’d finished prepping her for the transfer, while once again reassuring me that I couldn’t have known.

But of course I could; I’m her mother, aren’t I? The one who’s supposed to protect her from harm and keep this kind of stuff from happening in the first place.

Fat lot of good I was at that, I thought sniffing.

I stood up and began pacing, wearing a path in the linoleum floor as I waited to see my daughter.

‘Come on, Kate, try to relax,’ Lucy said as she fought back a yawn. It was now three o’clock in the morning. I had already told her repeatedly that she should go home to her own family, but she’d insisted on staying. ‘Rosie’s in good hands – think positive.’

I shook my head. ‘No, if I sit down, I’ll drive myself crazy thinking.’

About how this was all my fault. How I should have known. Why had I waited three whole days before getting her seen to, assuming she could just fight this on her own?

Right then, a nurse entered the general waiting area and gave me a gentle smile. It was enough to make me want to run over and hug her, yet I still couldn’t be sure if it meant…

‘Rosie’s sleeping now, and we have her on an antibiotic drip. The ambulance should be ready soon, and you’re free to go back in and sit with her while we wait.’

Almost sick with relief, I thanked the nurse and looked quickly at Lucy, who offered to head back to the house to bring me some toiletries and clothes – things I hadn’t had the time or the foresight to grab when we hightailed it over here hours ago.

I nodded my assent and she asked me if there was anything I needed specifically, but my mind was blank. I didn’t care what she brought me frankly, because I couldn’t recall a thing that I needed as much as I wanted to be by my little girl’s side. Hold her close, keep her safe.

Like I thought I’d been doing up to now.

On entering Rosie’s hospital room, I was immediately struck by how big the bed was and how small and fragile she was. My heart felt like it was breaking.

My God; she’s only five years old…

She was so pale and she had monitors and machines all around her, tracking every heartbeat, every breath. I walked slowly to the side of the bed and sat down, taking Rosie’s little hand in mine and murmuring, ‘Mummy’s here, buttercup. It’s going to be OK.’

But was it? a small voice in my mind asked. Again, my brain instinctively tried to go clinical on me – it was ready to spout off the measles statistics that I had been trying not to think about since I first spotted that telltale rash. I tried to tell it to shut up.

It’s just pneumonia – the antibiotics will sort it, it will be OK.

I worked my hardest to take Lucy’s advice and try to think positive, but my mind was too busy lecturing me that there were no guarantees from one minute to the next.

I understood that lesson better than most.

Chapter 8

The following week, Madeleine felt herself breathe a sigh of relief and offered up the quietest of thankful prayers as the GP took another look into Clara’s mouth and nodded.

Her rash still looked angry and sore, but her fever had all but disappeared, thank goodness. Some colour had returned to her cheeks, and today – a week since first displaying any signs of illness – Madeleine’s five-year-old was looking much more like herself.

Dr Barrett stood up and took a final glance down at Clara. ‘It looks like you are on the mend, princess,’ he said with a smile. ‘You’re a very lucky girl.’ His smile disappeared as he looked at Madeleine. ‘As are you,’ he added in a grave tone.

She kissed her daughter’s forehead, tears of relief pricking at the corners of her eyes, but her attention was returned to Dr Barrett when he cleared his throat and motioned with a sharp jerk of his head that he wanted to speak with her – privately.

She turned to leave the room and dutifully followed in his wake.

‘When will Tom be home?’ Dr Barrett enquired. In his sixties, the Knockroe doctor had been on first name terms with Madeleine’s family for years, and had been her GP since she was a child. She secretly wondered when he was going to retire. Tom said that Frank Barrett would retire at his funeral. He was probably right.

‘Not until later. He had to get back to work. He was here for the first few days, of course, but when it looked like she was out of the woods, he went back yesterday.’

Tom had been wonderful at keeping poor Clara’s spirits up, especially when one day he’d arrived home with, of all things, a blow-up kayak and a huge cuddly dolphin, promising their little girl that once she was all better, he’d take her out on the water like they did in Florida. This had raised a much needed smile from her rash-covered face, and even a few giggles when Tom and Jake proceeded to re-enact on the floor of her bedroom the loveliest moment of their trip; a memorable day out on the gulf when a family of blue dolphins had appeared and proceeded to jump up and down alongside their kayak, delighting them all, especially Clara.

‘He only has so much annual leave left unfortunately, and we have holidays booked for the summer,’ Madeleine babbled to the doctor, which earned her a stern harrumph. ‘I’m sorry, you’re right – that shouldn’t matter at a time like this.’

Especially when it had been a holiday that had got them into all this trouble in the first place.

‘You’re right, she must have picked it up on the flight back from Florida,’ Tom had agreed, when the doctor first came to examine Clara, echoing Madeleine’s early assessment.

On the GP’s advice, her husband had been in touch with the health board to report the incident and put them on alert for potential contamination amongst other passengers.

‘The timeline does sound right,’ the doctor concluded. ‘You got back, when – Saturday week? So she would have been exposed about ten days prior to showing any symptoms. Unfortunately, further exposing her classmates at Applewood in the ensuing time,’ he’d added pointedly, and, thinking of little Rosie O’Hara, Madeleine winced.

Now Dr Barrett turned to face her as they reached the living room. ‘I don’t know if you and Tom are really cognisant of just how lucky your family is – how lucky Clara is. Especially when you already dodged a bullet with Jake.’ He narrowed his eyes at her from behind his spectacles and ran a hand through his full head of shockingly white hair. Madeleine sensed a lecture. She wished Tom was here – especially as she guessed what was coming next. It was so hard having to defend their position over and over – mortifyingly difficult actually, given what they’d just been through. Her husband was much better than she at arguing the reasons behind their decision not to vaccinate Clara, and Tom had for the most part taken this recent misfortune in his stride.

‘We just need to wait things out, Maddie. She’ll be fine. We’ve been through this before,’ he reassured, when, after Clara’s diagnosis, Madeleine had castigated herself for their failures. But Tom had once again proceeded to reiterate the reasons why they had decided against the jabs in the first place, outlined their full decision-making process when Jake was a baby and arrived at the same conclusion. ‘We said the risk was one we weren’t willing to take, and now it’s time for us to stand by that,’ he’d repeated gently, while Madeleine thought it was all fine and well to make such decisions without having to face the fallout of the reality: namely a sick child who was feverish and uncomfortable.

But, in truth, Clara did seem to be fighting it well, and now, thank goodness, looked to be in the clear.

‘I need to encourage you again,’ Frank Barrett reiterated. ‘When Clara is fully recovered, go and get your children protected against the rest of all these godforsaken illnesses medicine conquered years ago. I’m serious, Madeleine.’ She put up a hand, trying to appease him, but he continued. ‘No, as your doctor, it is my job to say this. You know, there are a lot of GPs in this country who wouldn’t even allow your kids near their surgery. The only reason I haven’t had that policy with you is because I have known your family for ever. But I have to put my foot down now. Do you know just how bad this could have been? Do you have any idea? I’m receiving complaints from parents all over Knockroe and beyond. Madeleine, they don’t want their kids around yours – especially not at school.’

‘Please, Frank,’ said Madeleine, trying to keep her voice from quivering. ‘You know this is something that Tom and I have always felt very strongly about—’

‘Bah!’ Dr Barrett bellowed, throwing up his hands in frustration. ‘Nonsense. Conspiracy theories against the pharmaceutical companies. For heaven’s sakes, Madeleine, you know those autism studies were debunked years ago. I thought you were smarter than that; I know you are. All vaccines have ever done is eradicate serious illness. Do you know how many people in Third World hellholes would love to have access to something as simple as the freely distributed preventative medicine we take for granted? Do you know how many lives it would save?’

The doctor sighed heavily and dropped onto the sofa, seemingly exhausted. He looked at one of the plush throw pillows that he had disturbed from its artful arrangement and appeared thoughtful.

Madeleine could sense him softening somehow – like his rant had run out of steam. She didn’t know what to say to him. She understood his point of view, of course she did. But they’d been through this time and time again when the kids were younger.

‘Do you want a glass of water? A cup of tea, maybe?’ she asked kindly. He had done so much for her family over the last week, and she understood his stress.

Dr Barrett shrugged. ‘Tea would be great. Thank you.’

Madeleine retreated to the kitchen, vaguely aware this was one room of the house that had yet to be completely rescued from neglect when Clara was in the throes of her illness. And, as if the house wasn’t bad enough, after the last week, Madeleine knew that she too badly needed taking in hand. She put a hand up and ran it through her hair, now flat and straggly, and she guessed her unmade-up face looked haggard, and a million miles from her bubbly blonde TV persona.

Washing her hands, she swallowed the compulsive urge to automatically grab the bleach and begin scrubbing things down right there and then – to try and restore order. Instead she put the kettle on and brought it to a boil. She pulled a teapot down from the cabinet as she eyed the wine glasses that were housed right above it.

What I wouldn’t give for one of you bad boys just now, she thought ruefully. Alas, it was barely noon and she wasn’t one of those people. Not yet at least.

Though her Mad Mum alter-ego would probably advise her to go right ahead.

Allowing the tea to steep, Madeleine closed her eyes and thought about what Dr Barrett had said. He was right, of course. She knew that they had been lucky in that it hadn’t been anything more serious. Clara was on the mend.

They’d got through it, dodged another bullet. Everything was going to be OK.

She nodded as if to reassure herself of this as she placed the teapot and cups on a silver tea tray that had belonged to her mother. She knew it was a bit old-fashioned, but there was also something about it that was just so nicely ceremonial. She had always loved it and took it out every chance she could. Though Tom had kept the basics stocked up, unfortunately there were no biscuits or anything else to offer the doctor, and a trip to the supermarket was long overdue. She sighed. The last week had well and truly been utter chaos, but at least things were looking up now.

She walked back into the living room and set the tray on their walnut coffee table, taking extra care not to scratch the finish. Pouring a cup of tea, Madeleine looked at the doctor and asked, ‘Sugar?’

Dr Barrett shook his head. ‘Just milk will do. Thank you.’

The doctor took a hesitant sip and closed his eyes briefly, as if allowing himself a brief respite as the warmth of the liquid spread through his body. Suddenly, he reopened his eyes and placed his cup and saucer on the coffee table. Something about his demeanour had changed once again, as if it was time to get back to business.

‘You know that little Rosie O’Hara is in hospital?’

Madeleine looked down at her milky tea and nodded solemnly. ‘I know, I heard.’ Lucy had filled her in on the news – that on Monday she had gone with Kate to the local clinic because Rosie’s fever had suddenly spiked. And that the little girl had soon after been transferred to Dublin.

Returning her eyes to meet Dr Barrett’s, she had the uncanny feeling that he was studying her. Gauging her reaction. Of course he’d given her that lecture before too – about social responsibility and their contribution (or lack thereof) to herd immunity.

But how could you realistically proceed with something you truly felt was unsafe? Especially when there was no law against not vaccinating.

‘She’s in a critical condition, Madeleine. I don’t know if you know that. She has pneumonia, and some swelling in her brain apparently. She’s not going to have an easy road of it. Not like Clara.’

Madeleine’s throat went dry. Why was he telling her this? To make her feel guilty? Trying to blame her outright for Rosie’s condition? As if she didn’t feel bad enough.

Thanks to Lucy, she was all too aware that her daughter was being blamed by other Knockroe parents – and the school – for infecting Rosie. She didn’t need to be made to feel guilty about that from the family doctor as well.

Madeleine placed her cup and saucer on the tray and stood up. She appreciated the house call that Dr Barrett had made, but now it was time for him to go. She had more than enough to do around the house and she still had Clara to attend to.

And this whole conversation was making her feel really uncomfortable.

‘I’ve already sent Kate our best wishes. I know what she’s going through, after all.’ Madeleine intended her words to sound soft, but as they fell from her lips she realised there was more of an edge to them than she’d intended.

But she just couldn’t face any more guilt, any more regret. This, taken with the stress and worry about Clara over the last week, was getting on top of her. What was done was done and there was nothing Madeleine could do about it now. She couldn’t go back and change things or stop Clara from contracting the disease. The time for such decision-making was years ago, long gone. And at that time, she and Tom had made the decision that felt right, that was the best one for their family. She couldn’t think about the impact of that choice on other people just now. It was all too overwhelming.

Madeleine just wanted the doctor to leave so she could deal with this on her own, away from stern glares and accusing tones. Though if this was what her doctor – a close acquaintance – was saying, she wondered what strangers or indeed other locals would say when they heard about Rosie’s hospital admission.

Dr Barrett clearly picked up on the mood. ‘Well, I suppose that I should be going,’ he said, standing up. ‘Let me know if there is any change with Clara. Otherwise, I think she is indeed on the mend. But again you and Tom should think about what I said about the other jabs. It’s still not too late.’

He focused a keen eye on Madeleine then and she felt as if all of her thoughts, doubts, and worries were on display. Incredibly, despite her relief that Clara was on the mend, this visit had actually made her feel worse; had sent her entire world out of whack.

It was truly awful that little Rosie was in hospital; there was no question about that. She felt for Kate and she was desperately sorry that Clara’s infection had played some part in that. It wasn’t her daughter’s fault though; these things were always a risk, and nobody had any control over how another child might fight infection.

And, more to the point, wasn’t it common knowledge that Rosie was unvaccinated too?

In any case, Clara was going to be OK, that was the main thing.

It was the only thing that Madeleine should be thinking about just then.