Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

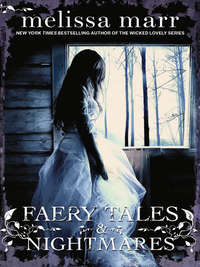

Kitabı oku: «Faery Tales and Nightmares»

Dedication

To the Rathers

(aka the wonderful readers

on the WickedLovely.com fan site),

who’ve been such a joy to me

these past several years.

Thank you for conversations,

teas, and fab art.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Where Nightmares Walk

Winter’s Kiss

Transition

Love Struck

Old Habits

Stopping Time

The Art of Waiting

Flesh for Comfort

The Sleeping Girl and the Summer King

Cotton Candy Skies

Unexpected Family

Merely Mortal

Other Books by Melissa Marr

Copyright

About the Publisher

T’S NOT ALWAYS AS EASY TO SEE THE PATH when you’re on it, but looking back is often much clearer. In 2004, I wrote a short story, “The Sleeping Girl,” that turned into a novel (Wicked Lovely) that evolved into a series. At the time, I was homeschooling my kids, reading adventure with my son and YA books with my daughter, and still teaching university. A few years before that, I’d taught two defining courses. One was called “Girlhood Narratives.” It started with fairy tales and worked forward into novels. The second was simply called “The Short Story.” In retrospect, it’s pretty easy to see that my children and my teaching were influential in writing the fairy tale that started my career.

T’S NOT ALWAYS AS EASY TO SEE THE PATH when you’re on it, but looking back is often much clearer. In 2004, I wrote a short story, “The Sleeping Girl,” that turned into a novel (Wicked Lovely) that evolved into a series. At the time, I was homeschooling my kids, reading adventure with my son and YA books with my daughter, and still teaching university. A few years before that, I’d taught two defining courses. One was called “Girlhood Narratives.” It started with fairy tales and worked forward into novels. The second was simply called “The Short Story.” In retrospect, it’s pretty easy to see that my children and my teaching were influential in writing the fairy tale that started my career.

Since then, I’ve continued to mix fairy tales and folklore together in novels and short stories. They’re scattered in anthologies, ebook-only editions, and special editions of my novels, so I figured it might be nice to have some of them together in one book.

Well over half of these pages are taken up by Wicked Lovely world stories; the rest of the pages are reserved for other worlds. These are stories pulled from lore and nightmares, set in places I’ve visited and places I’ve imagined. In the tales, you’ll find a selchie story influenced by Solana Beach, CA; a tale of vampires inspired by parties I once went to in a dead-end town I won’t name; a goblin encounter set in the woods where I once picked berries; and a tale of dark contentment in a mountain town that owes a debt of gratitude to a Violent Femmes song I love. Of course, you’ll also spend time with the Wicked Lovely faeries who have lived in my head and my novels since 2004. I hope you enjoy them.

HE GREEN GLOW OF EYES AND SULFUROUS breath shimmer in the fog as the Nightmares come into range. The horses’ steel-sharp hooves rip furrows in the field, trampling everything in their path.

HE GREEN GLOW OF EYES AND SULFUROUS breath shimmer in the fog as the Nightmares come into range. The horses’ steel-sharp hooves rip furrows in the field, trampling everything in their path.

“Over here!” my companion dog calls out to them, exposing me.

I didn’t know he could speak, but there is no mistaking the source of the sound—or the fact that I am trapped in a field with Nightmares bearing down upon me.

The dog shakes, and his glamour falls away like water flung from his fur. Under his disguise, my helpmate is a skeletal beast with holes where its eyes should be.

“Run,” it growls, “so we can chase.”

I want to, but much like the rest of the things I want my legs to do, running is no longer an option. If I could still run, I wouldn’t be alone on the night when Nightmares walk free. If I could still run, I’d be out in costume trick-or-treating with my friends.

“I can’t run.”

I hobble toward an oak that stands like a shadow in the fog.

The monstrous dog doesn’t stop me as I drop my crutches and pull myself onto the lowest branch. It doesn’t stop me as I try to heave myself higher.

“Faster!” it calls out to the Nightmares, which are almost upon me.

The only question left to answer is whether their running or my climbing is quicker.

NCE—A LONG TIME AGO BEFORE CHANGE had come—there was a girl whose father was a king. Now, this was when there were a great many kings, so Nesha did not think it strange to be the daughter of a king. And though she had no brothers or sisters, Princess Nesha was happy—but for one thing. Nesha had within her the kiss of winter. When she sighed, her breath rolled out in an icy chill. When she blew a kiss to her father across their great hall, frost flowers formed on every dish.

NCE—A LONG TIME AGO BEFORE CHANGE had come—there was a girl whose father was a king. Now, this was when there were a great many kings, so Nesha did not think it strange to be the daughter of a king. And though she had no brothers or sisters, Princess Nesha was happy—but for one thing. Nesha had within her the kiss of winter. When she sighed, her breath rolled out in an icy chill. When she blew a kiss to her father across their great hall, frost flowers formed on every dish.

In winter, Nesha could drape snows over every hill without fear, but in the summer, if she forgot herself and blew the white tops of dandelions gone to seed, if she laughed too freely and her cold breath spilled out, she would wither whole fields, blighting the crops her people needed to survive.

Her father built her a great tower with no windows through which her cold breath could escape, but Nesha wept at being alone and enclosed.

So Nesha left her tower and sought out her father in the great hall. Gazing at the fields she could see through the tall window before her, she said, “I do not belong in this place with its long months of warmth and sun.”

Though he knew she was right, the king wept, for he loved his daughter. “Nesha, stay. We can find a way.”

She turned and rested her head against her father’s shoulder, thinking of the windowless room and months indoors, of trying not to laugh for fear of the cold air that slipped through her lips. “No. I must go.”

The king’s warm tears fell onto her cheek, but he said nothing.

Nesha did not sigh or weep; she gazed out the window at the new plants in the fields, wondering why she had been cursed so cruelly.

The next morning the king walked his daughter to the edge of the wood. He held her only briefly. “Be safe.”

After a few silent tears, Nesha clutched her staff and strode off into the dark wood.

She traveled for many days. One evening as she sat on a felled tree, she let her eyes drift closed. She imagined the icy rim that encircled the northernmost edge of the land, hoping she would soon reach it, and worrying she would not find welcome once she did.

When she opened her eyes, a great ice-bear stood before her. The bear lay down at her feet, his fur glistening as if he had been bathed in precious oils.

“What are you doing here?” she murmured, her voice trembling only a bit.

As Nesha looked into his eyes, she saw her own nervousness reflected there, and her fear disappeared like frost under a spring sun. “Are you lonely too?”

So she closed her eyes and exhaled gently—giving the bear thick snow upon which to rest.

The ice-bear stretched out in the snow and stared up at her until she climbed from the log and sat next to him.

She opened her pack and drew out a piece of thick meat. She broke off a small piece for herself, then offered the rest of the meat to the bear.

The ice-bear gently accepted the meat from her hand.

“Perhaps we can be lonely together.” Nesha lay down to rest alongside the bear in their pile of snow.

When Nesha awoke the next morn, she found that the bear had curled around her, holding her body close to his furred limbs.

After a small meal, Nesha readied herself to travel.

The ice-bear lay flat in front of Nesha and glanced at her. He tossed his head toward his back.

Nesha ran her hand over his thick pelt. Then, she stepped past him. “Come. If you’re to travel with me, we must be off.”

The ice-bear bounded past Nesha, and once again lay prostrate before her.

She laughed and stepped past him once more. “We’ll not get far if we stop to play.”

For the third time the ice-bear leaped before her—this time, though, when he stretched his great length across the path, his body spanned the space between two boulders. She could not walk around him.

Grumbling, Nesha began to climb over him, but once she was atop his back, he stood.

“Oh,” she murmured, awed that such a great beast would carry her. She was still tired from her days of walking, so she said, “For a short while, I suppose there’s no harm in it.”

So, atop the ice-bear, Nesha journeyed through the forest. The only sounds were the rippling of waters and the cries of creatures in the dense canopy overhead. A solitary owl called out from a hidden perch; squirrels chattered in their secret language. And despite her worries, Nesha felt joy as the bear ambled under pine boughs and outstretched branches.

Eventually, though, the ice-bear paused and lay flat.

Nesha slid to the ground. Beside her were thick berry brambles, heavy with fruit. With his muzzle, the ice-bear gently nudged her toward the fruit.

“I see.” She smiled and began to pick the berries.

As she did so, the ice-bear clambered down the embankment to the swirling river. With his massive paws he pulled fish from the current.

Nesha glanced at the bear standing in the cold water, gathering food. “What a wise beast you are!”

After a while, the ice-bear had not returned up the hill, so Nesha put away the fruit she had collected and went to the top of the muddy embankment. Below her, she saw the bear looking first at the fish he’d caught and then gazing up the hill.

He has no way to carry them, she realized. Gingerly, she climbed down the slope, gripping tiny saplings for balance as she went.

“Let me,” she said, peering into the bear’s eyes. Then she blew softly on the fish, freezing them so they were easier to grasp, and wrapped them into a cloth from her pack.

The ice-bear brushed her shoulder with his muzzle in what she now knew as a friendly gesture. Then, unable to stretch out on the briar-heavy riverside, the ice-bear bent so Nesha could scramble up again.

Once she was seated, the bear rapidly climbed up the hill and resumed their path, and Nesha absently stroked her fingers through his soft fur—thankful to have a companion on her journey.

And thus Nesha forgot the sorrow of carrying a curse. Together, she and the ice-bear found a rhythm to their travels, stopping to gather food when the chance presented itself and continuing on through the still forest.

Though she thought often of her home and her father, after traveling together for a full moon’s passing, Nesha could scarcely imagine life without her ice-bear. In the evenings, they curled in a snowy nest she made for them. During the day, she traveled upon his soft fur and gazed at the increasingly cold land. Tall trees dotted the ground, and the river had a growing crust of ice upon it.

“I’ve never seen anything so lovely,” she whispered.

The ice-bear glanced back at her, with a soft almost-growl, and continued on his way.

Nesha knew the ice-bear was unusual, but as they traveled onward she realized that the ice-bear followed a definite path. When Nesha thought to suggest another way, the ice-bear plopped down and refused to move.

One night after they neared the colder lands, the bear led her to a cave. Inside the cave, spires hung like ice from above; water trickled in rivulets down those stalactites. Nesha whispered, “Where do we go? Do you take me to your home?”

The bear simply gazed at her.

“Will there be others there? What if they aren’t as kind as you?” She leaned against the ice-bear.

The bear moved closer; his muzzle pressed against her shoulder.

“I’m sorry,” she murmured as she stroked his head. She closed her eyes. “You’ve been truly wonderful, but I miss human voices. I miss …”

Nesha paused. The thick pelt under her hand no longer felt right. Instead of coarse fur, her hand rested on silk-soft hair. She jerked her hand away and opened her eyes.

A boy stood beside her. His hair was as dark as the night sky; it was so long that it fell like a heavy blanket touching the earth, hiding a human form.

“Where? Who?” Nesha stepped backward, her words tangled as she stared at the boy. Frantically, she looked for her ice-bear.

“I knew no other way to show you,” the boy was saying. He had not made any movement toward her. “Now that we’ve reached my village—”

“Village?” Nesha looked around her.

From the tunnels other ice-bears, including several cubs, approached.

The boy nodded. “My home …”

“Where is my ice-bear?” Nesha knew the answer, but she needed to hear him say the words.

“I’m here.” The boy took a step toward her, hands outstretched. He was clad in clothes made of a heavy brown cloth, decorated with ivory beads. Over this he wore a fur cloak. “I caught the fish we eat.” He gestured toward the still-glowing embers on the cave floor where she had cooked their meal. “I carried you through the rains and over the gorge.”

“You are a boy.”

“I am.” He smiled tentatively. “And I am the beast who slept in the nests of ice and snow that you made. My people are not bound to one form …. I am called Bjarn.”

Nesha sat down. What he said was stranger than anything she’d ever heard, but as he moved, she knew it to be true. The boy-who-was-a-bear tilted his head a bit when she spoke to him, just as the ice-bear had. The startling black eyes that stared from the boy’s face were the same eyes that had peered at her each morning when she woke. Bjarn spoke the truth.

Nesha wasn’t sure what question to ask first. “Why travel with me? Why bring me here?”

For a moment, Bjarn stood silently. When he spoke, his voice was rough. “The lands grow warmer. My people struggle with the heat; the months when the cold seems to grow less cause such sickness.” Bjarn sat down in front of her and took her hands. “Your gift … it would bring such peace to my people. The eldest suffer when the warmth grows too much. I am not skilled with words. I thought if I could bring you to my father, he would know what to say.” Bjarn looked at the other bears and then back at her. “Will you stay awhile with us?”

Nesha imagined people cherishing her cursed breath, a life where she was not feared. “And if I wanted to return home in the coldest months?”

Bjarn looked solemn as he said, “I would carry you there if you wished. Or if you’d rather, there are others who could carry you.”

As she considered what Bjarn had said, Nesha gazed at the waiting group of bears. Most sat nestled in the rocky crevices, but a couple wrestled with the cubs. She looked back at Bjarn. Though his form was different, Bjarn was the same kind creature he’d been as an ice-bear. “I would have you travel with me.”

“I would like that very much.” Smiling, Bjarn pulled her to her feet.

Clutching his hand in hers, she turned toward the mouth of the tunnels. “Can I meet them?”

He grinned and waved at the ice-bears. One of the largest ambled forward first.

“My grandmother stays in this form almost always since the snows are so brief.” Bjarn rested his face on the great bear’s head in a hug of sorts. “She had heard the stories whispered of you, of your gift, and so I traveled to find you ….”

“Thank you,” Nesha murmured to the bear, joyous at hearing her icy breath called a gift, at finding a home where she would be welcome in the months away from her father’s lands.

The bear rubbed her muzzle against Nesha’s arm.

Bjarn pointed at several cubs who were rolling perilously close to a cluster of stalagmites. “The youngest, my sisters, stay furred as much as they can. They race through the cave tunnels”—he paused and shook his head as one of the cubs hurtled toward another, larger bear—“until my father takes them out to explore the ice dunes and give the elders a bit of quiet ….”

And so long into the night they sat and talked, the girl who carried winter’s kiss and the boy who was a bear.

Thus began their new life. Bjarn still carried Nesha when they went out during the day, but now they were joined by Bjarn’s family. Now, for the first time in her life, Nesha could laughed freely, setting snow squalls to dance over the ledges. Her new family-who-were-bears did not fear her; instead, they spun and laughed in the cold air. And when they returned to the caves, Bjarn walked hand in hand with her—listening as she told him of her life and dreams, and telling her of his life and dreams.

This was the way of their lives for many months.

Then, one winter afternoon, the sky heavy with snow, Nesha said to Bjarn, “Come with me to see my father.”

Bjarn asked, “To stay?”

“No. This is my home.” She motioned toward the great white plain where the cubs were sliding in circles. “With them, with you. Now and always.”

“Always,” Bjarn repeated softly.

And so it was that Nesha shared the first of many kisses with Bjarn, the boy-who-had-become-her-beloved.

TOMORROW

EBASTIAN LOWERED THE BODY TO THE ground in the middle of a dirt-and-gravel road in the far back of a graveyard. “Crossroads matter, Eliana.”

EBASTIAN LOWERED THE BODY TO THE ground in the middle of a dirt-and-gravel road in the far back of a graveyard. “Crossroads matter, Eliana.”

He pulled a long, thin blade and slit open the stomach. He reached his whole forearm inside the body. His other hand, the one holding the knife, pressed down on her chest. “Until this moment, she could recover.”

Eliana said nothing, did nothing.

“But hearts matter.” He pulled his arm out, a red slippery thing in his grasp.

He tossed it to Eliana.

“That needs buried in sanctified ground, and she”—he stood, pulled off his shirt, and wiped the blood from his arm and hand—“needs to be left at crossroad.”

Afraid that it would fall, Eliana clutched the heart in both hands. It didn’t matter, not really, but she didn’t want to drop it in the dirt. Which is where we will put it. But burying it seemed different from letting it fall on the dirt road.

Sebastian slipped something from his pocket, pried open the corpse’s mouth, and inserted it between her lips. “Wafers, holy objects of any faith, put these in the mouth. Once we used to stitch the mouth shut, too, but these days that attracts too much attention.”

“And dead bodies with missing hearts don’t?”

“They do.” He lifted one shoulder in a small shrug.

Eliana tore her gaze from the heart in her hands and asked, “But?”

“You need to know the ways to keep the dead from waking, and I’m feeling sentimental.” He walked back toward the crypt where the rest of their clothes were, leaving her the choice to follow him or leave.

TODAY

“Back later,” Eliana called as she slipped out the kitchen door. The screen door slammed behind her, and the porch creaked as she walked over it. Sometimes she thought her aunt and uncle let things fall into disrepair because it made it impossible to sneak in—or out—of the house. Of course, that would imply that they noticed if she was there.

Why should they be any different from anyone else?

She went over to a sagging lawn chair that sat in front of a kiddie pool in their patchy grass. Her cousin’s kids had been there earlier in the week, and no one had bothered to put the pool back inside the shed yet. The air was sticky enough that filling it up with the hose and lying out under the stars didn’t sound half bad.

Except for the part where I have to move.

Eliana closed her eyes and leaned her head back. One of the headaches she’d been having almost every day the past couple months played at the edge of her eye. The doctor said they were migraines or stress headaches or maybe a PMS thing. She didn’t care what they were, just that they stop, but the pills he gave her didn’t help that much—and were more money than her aunt felt like paying for all the good they did.

On to Plan B: self-medicate.

She tucked up her skirt so it didn’t drag in the mud, propped her boots on the end of the kiddie pool, and noticed another bruise on her calf. The bruises and the headaches scared her, made her worry that there was something really wrong with her, but no one else seemed to think it was a big deal.

She closed her eyes and waited for her medicine to arrive.

“Why are you sleeping out here?” Gregory glanced back at her empty front porch. “Everything okay?”

“Yeah.” She blinked a few times and looked at him. “Just another headache. What time is it?”

“I’m late, but”—he took her hands and pulled her to her feet—“I’ll make it up to you. I have a surprise.”

He’d slid a pill into her hand. She didn’t bother asking what it was; it didn’t matter. She popped it into her mouth and held out her hand. He offered her a soda bottle, and she washed the pill taste out of her mouth with whatever mix of liquor he’d had in with the cola. Unlike pills and other things, good liquor was more of a challenge to get.

They walked a few blocks in silence before he lit a joint. By the look of the darkened houses they’d passed, it was late enough that no one was going to be sitting on their stoop or out with kids. Even if they did look, they wouldn’t know for sure if it was a cigarette—and since Gregory didn’t often smoke, there was no telltale passing it back and forth to clue anyone in.

“Headaches that make a person miss hours can’t be”—she inhaled, pulling the lovely numbing smoke into her throat and lungs—“normal. That doctor”—she exhaled—“is a joke.”

Gregory slid his arm around her low back. “Hours?”

She nodded. Her doctor had given her a suspicious look and asked about drugs when she’d mentioned that she felt like she was missing time, but then she could honestly say that she hadn’t taken drugs. The drugs came after the doctor couldn’t figure out what was wrong. She tried the over-the-counter stuff, cutting out soda, eating different foods. The headaches and the bruises weren’t changed at all. Neither is the time thing.

“Maybe you just need to, you know, de-stress.” Gregory kissed her throat.

Eliana didn’t roll her eyes. He wasn’t a bad guy, but he wasn’t looking for a soul mate. They didn’t discuss it, but it was a pretty straightforward deal they had going. He had medicine that took away her headaches better than anything else had, and she did the girlfriend bit. She got the better part of the deal—meds and entry into every party. Headaches had taken her from stay-at-home book geek to party regular in a couple months.

“We’re here,” he murmured.

She took another hit at the gates of Saint Bartholomew’s.

“Come on, El.” Gregory let go of her long enough to push open the cemetery gate. It should’ve been locked, but the padlock was more decoration than anything. She was glad: crawling over the fence, especially in a skirt, sounded more daunting than she was up for tonight.

After he pushed the gate shut and adjusted the lock so it looked like it was closed, Gregory took her hand.

She imagined herself with a long cigarette holder in a smoky club. He’d be wearing something classy, and she’d have on a funky flapper dress. Maybe he’d rescued her from a lame job, and she was his moll. They partied like crazy because he’d just pulled a bank job and—

“Come on.” He pulled her toward the slope of the hill near the older mausoleums.

The grass was slick with dewdrops that sparkled in the moonlight, but she forced herself to focus on her feet. The world spun just this side of too much as the combined headache cures blended. At the top, she stopped and pulled a long drag into her lungs. There were times when she could swear she could feel the smoke curling over her tongue, could feel the whispery form of it caught in the force of her inhalation.

Gregory slipped a cold hand under her shirt, and she closed her eyes. The hard press of the gravestone behind her was all that held her up. Stones to hold me down and smoke to lift me up.

“Come on, Eliana,” he mumbled against her throat. “I need you.”

Eliana concentrated on the weight of the smoke in her lungs, the lingering taste of cheap liquor on her lips, the pleasant hum of everything in her skin. If Gregory stopped talking, stopped breathing, if … If he was someone else, she admitted. Something else.

His breath was warm on her throat.

She imagined that his breath was warm because he’d drained the life out of someone, because he’d just come from taking the final drops of life out of some horrible person. A bad person who—the thought of that was ruining her buzz, though, so she concentrated on the other parts of the fantasy: he only killed bad people, and he had just rescued her from something awful. Now, she was going to show him that she was grateful.

“Right here,” she whispered. She lowered herself to the ground and looked up at him.

“Out in the open?”

“Yes.” She leaned back against a stone, tilted her head, and pushed her hair over her shoulder so her throat was bared to him.

Permission to sink your fangs into me …. He asked. He always asked first.

Gregory knelt in front of her and kissed her throat. He had no fangs, though. He had a thudding pulse and a warm body. He was nothing like the stories, the characters she read about before she fell asleep at night, the vague face in her fantasies. Gregory was here; that was enough.

She moved to the side a little so she could lie back in the grass.

Gregory was still kissing her throat, her shoulder, the small bit of skin bared above her bra line. It wasn’t what she wanted. He wasn’t what she wanted.

“Bite me.”

He pulled back and stared at her. “Elia—”

“Bite me,” she repeated.

He bit her, gently, and she turned her head toward the gravestone. She traced the words: THERE IS NO DEATH, WHAT SEEMETH SO IS TRANSITION.

“Transition,” she whispered. That was what she wanted, a transition to something new. Instead she was stretched out in the dew-wet grass staring at the wingless angel crouched on the crypt behind Gregory. It was centered over the lintel of a mausoleum door almost as if it was watching her.

She shivered and licked her lips.

Gregory was pulling up her shirt. Eliana sighed, and he took it for encouragement. It wasn’t for him, though: it was for a fantasy that she’d been having every night.

Eliana couldn’t see the face of the monster. He’d found her again, though, offered her whispered promises and sharp pleasures, and she’d said yes. She couldn’t remember the words to the questions, but she knew he’d asked. That detail was clear as nothing else was. Shouldn’t fantasies be clear? That was the point, really: fantasies were to be the detailed imaginings to make up for the bleak reality.

She opened her eyes, pushing the fantasies away as headache threatened again, and she saw a girl walking up the hill toward them. Tall glossy boots covered her legs almost to her short black skirt, but at the top—just below the hem of the sheer black skirt—pale white skin interrupted the darkness of the sleek vinyl and silk skirt. “Gory! You left the party before we got there. I told you I wanted to see you tonight.”

Gregory looked over his shoulder. “Nikki. Kind of busy here.”

Undeterred, Nikki hopped up onto the gravestone beside Eliana’s head and peered down at them. “So what’s your name?”

“El … Eliana.”

“Sorry, El,” Gregory murmured. He moved a little to the side, propped himself up on one arm, and smiled at Nikki. “Could we catch you later?”

“But I’m here now.” Nikki kicked her feet and stared at Eliana.

Eliana blinked, trying to focus her eyes. It wasn’t working: the wingless angel looked like it was on a different mausoleum now. She looked away from it to stare at Gregory. “My head hurts again, Gory.”

“Shh, El. It’s okay.” He brushed a hand over her hair and then glared at Nikki. “You need to take a walk.”

“But I had a question for Elly.” Nikki hopped down to stand beside them. “Are you and Gory in love, Elly dear? Is Gory that special someone you’d die for?”

Eliana wasn’t sure who the girl was, but she was too out of it to lie. “No.”

“El …” Gregory rolled back over so he was on top of her. His eyes were widened in what looked like genuine shock.

Nikki flung a leg over Gregory so she was straddling both Gregory and Eliana; she leaned down to look into Eliana’s eyes. “Have you already met someone new then? Someone who you dream—”

“Nicole, stop it,” another voice said.

For a strange moment, Eliana thought it was the wingless angel on the crypt. She wanted to look, but Nikki reached down and forced Eliana to look only at her.

“Do stone angels usually speak?” Eliana whispered.

“Poor Gory.” Nikki shook her head—and then pressed herself against Gregory. “To die for a girl who doesn’t even think you’re special. It’s sad, really.”

He started to try to buck her off. “That’s not funn—”

Nikki pushed herself tighter to his back. “You seem like a nice guy, and I wanted your last minutes to be special, Gory. Really, I did, but”—she reached down and slashed open Gregory’s throat with a short blade—“you talk too much.”

Blood sprayed over Eliana, over the grass, and over Nikki.

And then Nikki leaned down and sank her teeth into the already bleeding flesh of Gregory’s neck.

Gregory arched and twisted, trying to get free, trying to escape, but Nikki was on his back, swallowing his blood and pressing him against Eliana.

Eliana started to scream, but Nikki covered her mouth and nose. “Shut up, Elly.”

And Eliana couldn’t move, couldn’t turn her head, couldn’t breathe. She stared up at Nikki, who licked Gregory’s blood from her lips, as the pressure in her chest increased. She tried to move her legs, still pinned under Gregory’s body; she grabbed Nikki’s wrists ineffectually. She scratched and batted at Nikki as everything went dark, as Nikki suffocated her.

Graveyard soil filled Eliana’s mouth, and a damp sensation was all over her. She opened her eyes, blinked a few times, and spit out the dirt. That was as much as she could manage for the moment. Her body felt different: her nerves sent messages too fast, her tongue and nose drawing more flavors in with each breath than she could identify, and breathing itself wasn’t the same. She stopped breathing, waiting for tightness in her chest, gasping, something. It didn’t come. Breathing was a function of tasting the air, not inflating her lungs. Carefully, she turned her head to the side.

She wasn’t in the same spot, but the same wingless angel stood atop a gravestone watching her.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.