Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

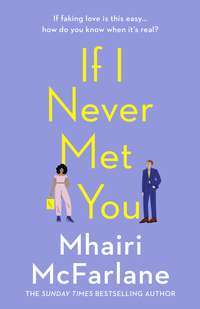

Kitabı oku: «If I Never Met You», sayfa 2

3

Laurie clambered out of the cab into the heavy smog of late summer air and the nice-postcode-quiet of the street, aware that while her senses were muffled by inebriation, neighbours with families would be lying in their beds cursing the cacophony that was someone exiting a Hackney.

The throbbing engine, sing-song conversation, slamming of a heavy door, the clattering of your big night out heels on the pavement.

Two weeks back, the sisters next door had managed to have such an involved back and forth for ten minutes about whose puke it was, Laurie had been tempted to march out in her pyjamas and pay the soiling charge herself.

Ah, middle age beckoned. Hah, who was she kidding, Dan called her ‘Mrs Tiggywinkle.’ She was the girl in halls who kept a row of basil plants alive in the shared kitchen.

Loud-whispering ‘keep the change,’ to the driver, she ducked under the thick canopy of clematis that hung over the tiled porch, grabbing blindly for her keys in the depths of her handbag, and once again thought: we need a light out here.

She’d been infatuated with this solid bay-fronted Edwardian semi from the first viewing, and knackered their chances of driving a hard bargain by walking around with the estate agent gibbering on about how much she adored it. They bought at the top of what they could afford at the time, and in Laurie’s opinion it was worth every cent.

Their front room, she liked to point out, was the spit of the one on the sleeve of Oasis’ Definitely Maybe, right down to the stained glass, potted palm and half-drunk red wines usually strewn around.

There was a honey-yellow glow from under the blinds, so either Dan had left the lamp on for her or he was having another bout of insomnia, passed out on the sofa in front of BBC News 24 with the sound on low, feet twitching.

Laurie felt a small rush of love for him, and hoped he was up. As much as it was authentic, she knew it was also in some part due to spending a trying evening surrounded by strangers, feeling homesick and out of place. Not belonging.

As a ‘person of ethnic origin’ who grew up in Hebden Bridge, she didn’t care to revisit that feeling often. Even in a cosmopolitan city she got the OH I LOVE YOUR ACCENT? EE BAH GUM jokes. ‘You don’t often hear a black girl sound that northern, except for that one out of the Spice Girls,’ a forthright client had said to her once.

She thought Dan might have waited up for her, but the moment she saw him, she knew something was badly off. He was still dressed, sat on the sofa, feet apart, head bowed, hands clasped. The TV screen was a blank and there wasn’t any music on, no detritus of a takeaway.

‘Hi,’ he said, in an unnatural voice, as Laurie entered the room.

Laurie was an empathetic person. When she was small she once told her mum she thought she might be telepathic, and her amused mother had explained that she was just very intuitive about emotions. Laurie was, as her dad said, born aged forty. Better than being born aged nineteen and staying there, she never said in reply.

The air was thick with a Terrible Unsaid and her antennae picked it up easily enough to feel completely nauseous.

Laurie clutched the jangle of her keys to her chest, with their silly fob of Bagpuss, and said: ‘Oh God, what? Which of our parents is it? Please say it now. Say it quickly.’

‘What?’

‘I know it’s bad news. Please don’t do any build up whatsoever.’

Laurie was about six or seven drinks in the hole and yet in an instant, completely, pin-sharp sober with adrenaline.

Dan looked perturbed. ‘Nothing has happened to anyone?’

‘Oh? Oh! Fuck, you scared me.’

In relief, Laurie flumped down onto the sofa, arms flung out by her sides like a kid.

She looked at Dan as her heart rate slowed to normal. He was regarding her with a strange expression.

Not for the first time, she felt appreciation, a bump of pride in ownership, admiring how much early middle age suited him. He’d been a kind of jolly-looking chubby lad in their youth, puppyish cute but not handsome, as her gran had helpfully noted. And with a slight lisp that he hated, but oddly enough, always had women swooning. Laurie always loved it, right from the first moment he had spoken to her. Now he had a few lines and silver threaded in his light brown hair, the bones of his face had sharpened, he’d grown into himself. He was what the girls at work called a Hot Dad. Or, he would be.

‘You couldn’t sleep again?’ she asked. His insomnia was a recent thing, due to him being made head of department. Three a.m. night sweat terrors.

‘No,’ he said, and she didn’t know if he was saying no, I couldn’t sleep or no, that’s not it.

Laurie peered at him. ‘You alright?’

‘About you coming off the pill next month. I’ve been thinking about it. It’s made me think about a lot of things.’

‘Has it …?’ Laurie suppressed a knowing smile. The atmosphere and anxiety now made sense. Here we go, she thought. This was a clichéd moment in the passage to parenthood. It belonged in a scripted drama, shortly after a couple had seen two blue lines on the wee stick.

Should he trade in the car for something bigger? Would he be a good father? Would they still be the same?

1. Nah. There’s no room out there to park a people carrier anyway.

2. Of course! He could try to be less sulky, perhaps, but that was about it. Kids had a way of automatically curing excess self-pity, from what Laurie could tell. At least for the initial five years.

3. Yes. The same, but better! (Actually, Laurie had no idea about the last answer. If they procreated, it would be the best part of two decades before this household belonged to the two of them again, and inviting a tyrannically needy midget intruder to disturb their privacy and contented status quo was scary.)

But the done thing in a couple was to pretend to be sure about the imponderable things, whenever the other person needed comfort. If necessary, deploy outright lying. Dan could pay her back when she asked tearfully after returning from a failed shopping trip, whether her body would ever look like it did before.

‘I don’t know how to say any of this. I’ve been sitting here since you left trying to think of the right words and I still can’t.’

This was hyperbole, because Laurie left him having a shower with the Roberts radio broadcasting the football game, but she didn’t say so.

‘Look,’ Dan said. ‘I’ve realised. I don’t want kids. At all. Ever.’

The silence lengthened.

Laurie sat up, with some effort, given her foolish shoes – strappy silver slingbacks she fell for in Selfridges, ‘look good with plum toenails’ according to the sales girl – weren’t anchoring her to the floor very steadily.

‘Dan,’ she said gently. ‘This doubt is totally normal, you know. I feel the same. It’s frightening, when it’s about to become real. But we can do it. We’ve got this. With having a kid, you hold hands, and jump.’

She smiled at him, hoping he’d snap out of it soon. It felt like a role reversal, him demanding a deep talk, her wanting to do enough to make him feel taken seriously so she could go to bed. Dan was flexing his fingers, steepled in his lap, not looking at her.

‘And it’s me who has to push it out,’ Laurie added. ‘Don’t think I haven’t googled “third-degree tearing”.’

He wouldn’t be easily joked out of this, she realised, looking at the depth of his frown lines.

She felt them running at different speeds, her carrying the noise and trivia of the night out with her like a swarm of bees, him evidently having spent a pensive period staring at the shadows in the sombre Edward Hopper print they hung over the fireplace, worrying about the future.

‘It’s not just having kids. I don’t want anything that you want. I don’t want … this.’

He glanced around the room, accusingly.

Stripped floorboards?

‘What do you mean?’

Dan breathed in and out, as if limbering up for a feat of exertion. But no words followed.

‘… You want to put it off for a few years? We talked about this. I’m thirty-six and it could take a while. We don’t want to be mucking about with interventions and wishing we’d got on with it … you know what Claire says. If she knew how great it would be, she’d have started at twenty.’

Invoking this particular member of their social circle was a stupid misstep, and Laurie immediately regretted it.

Claire was both a massive bore about her offspring and a general pain in the hoop. Ironically, if they hadn’t suffered her, they might’ve have reproduced already. Occasions with her often concluded with one or other of them muttering: you’d tell me if I ever got like that, right?

‘You know what they say. There’s never a perfect time to have a baby,’ Laurie added. ‘If you—’

‘Laurie,’ Dan said, interrupting her. ‘I’m trying to tell you that we don’t want the same things and so we can’t be together.’

She gasped. He’d say such an ugly, ridiculous thing to get his point across? Then she did a small empty laugh, as it dawned on her: this was how much men could fear maturity. It ought not to be a revelation to her, given her dad, and yet she was badly disappointed in Dan.

‘Come on, are you really going to turn this into a full-blown emergency and make me say having a family is a deal breaker, or something? So it can all be my fault when it’s had us up five times in a row?’

Dan looked at her.

‘I don’t know how else I can say this. I’m not happy, Laurie.’

Laurie breathed in and out: Dan wasn’t bluffing, he wanted a direct assurance from her she’d not come off the pill. She’d have to hope they revisited the idea in a year. She was aware that it could mean their window of opportunity closed completely. And she could end up resenting Dan. There’d be no playing tricks, pretending to take the pill when she wasn’t and whoops-a-daisy. That was how Laurie was conceived and she knew the consequences were lifelong.

‘Is this purely because I want kids?’

She would take it off the table to stay with him, she knew that in a split second’s consultation with herself. It was unthinkable to do anything else. You didn’t lose someone you loved, over hypothetical love for someone who didn’t yet exist. Who might never exist.

‘That, other things. I’m not … this is not where I want to be any more.’

‘OK,’ she said, rubbing her tired face, feeling appalled by how extreme he’d been prepared to be, in order to get his way.

She felt like she might cry, in fact. They’d had fights before where very occasionally one or the other of them had vaguely threatened to leave, usually when drunk and in their dickhead twenties, and whichever of them had said it felt sick with guilt the next day.

Pulling this now, at their age, was beneath Dan, however much he was bricking it over the responsibilities of fatherhood. It was really unkind.

‘… OK, you win. Regular pill-taking for the time being. Christ, Dan.’

Dan looked at her with a stunned expression and Laurie froze, because again, she could read it.

He wasn’t stunned she’d agreed. It wasn’t a gambit. He wanted to split up.

She finally understood. Understood that he meant it, that this was it.

Absolutely everything else was completely beyond her comprehension.

4

When people did monumentally awful things to you, it seemed they didn’t even have the courtesy of being original, of inflicting some unique war wound, a lightning-bolt-shaped scar. These reasons were prosaic, dull. They were true of people all the time, but they weren’t applicable to Dan and Laurie. They were going to be together forever. They agreed that openly as daft lovestruck teenagers and implicitly confirmed it in every choice they’d made since. No commitment needed checking or second thinking, it was just: of course. You are mine and I am yours.

‘But nothing’s changed?’ Laurie said. ‘We’re like we’ve always been.’

‘I think that’s part of the problem.’

Laurie’s mind was occupying two time zones at once: this surreal nightmare where her partner of eighteen years, her first and only love, her best friend, her ‘other half’, was sitting here, saying things about how he’d sleep in the spare room for the time being and move out to a flat as soon as possible. She had to play along with it, because he was so convinced. It was like colluding with someone who’d become delusional about a dream world. Follow the rabbit.

Then there was the other time zone, where she was desperately trying to make sense of the situation, to manage it and defuse it. He was only using words – no tangible, irreversible change had occurred. Therefore words could change it back again.

She’d always had a special power over Dan, and vice versa, that’s why they fell for each other. If she wanted to pull him back from this brink, she must be able. She only needed to try hard enough, to find the way to persuade him.

But to fix it, she had to grasp what was going on. Laurie prided herself on cold reading people like she was a stage magician, and yet the person closest to her sounded like a stranger.

‘How long have you felt this way?’ she asked.

‘A while,’ Dan said, and although his body showed tension, she could already tell he had relaxed several notches. Announcement made, the worst was over for him. She hated him, for a second. ‘I think I knew for sure at Tom and Pri’s wedding.’

‘Oh, that was why you spent the whole night in a strop, was it?’ Laurie spat. And realised the lunacy of that sort of point scoring, when the whole game had been cancelled. He wouldn’t go through with this. Surely.

Her stomach lurched. It was utterly ridiculous to take him seriously, and wildly reckless not to.

Dan made a hissing noise, shook his head. Whether he was dismayed at Laurie or himself wasn’t clear.

‘I knew none of that wedding fuss was for me. I knew that’s not where I was at, mentally.’

A painful memory came back to Laurie, because it turned out her senses hadn’t entirely failed her.

She recalled that the couples present had been corralled by the DJ for the first-dance-after-the-first-dance. She and a half cut, sullen Dan were forced into a waltz hold to Adele. She felt a sudden total absence of anything between them, not even a comfortable ease with each other’s touch, in place of a spark. It was like their battery was dead and if you pressed the accelerator it’d only make an empty phut-phut-phut. They shuffled round the floor awkwardly, like brother and sister, not meeting each other’s gaze. Then as soon as the song was over she forgot about it, and put it down to Dan not liking ‘Someone Like You’, or being told to do things.

He’d made a passive-aggressive show of going to sleep in the cab on the way back. Laurie felt she’d committed an unspecified crime all day, but when asked ‘What’s up with you?’ she’d got a belligerent ‘… NOTHING?’

But crap days in a long-term relationship were a given. You no more thought they might spell the end than you feared every cold could be cancer.

‘Is there someone else?’ Laurie said, not because she thought it possible but you were supposed to ask this, weren’t you? In this weird theatre they were playing out, at Dan’s insistence. They worked together – on a practical level alone, this seemed improbable.

‘No, of course not,’ Dan said, sounding genuinely affronted.

‘I don’t think you get to OF COURSE NOT me, do you?’ Laurie shrieked, anger breaking, causing Dan to flinch. ‘I think OF COURSE NOT is pretty much fucking unavailable to you right now, don’t you? We’ve stopped having any shared reality from what I can see so fuck off with your patronising OF COURSE NOTS.’

Dan was completely unused to seeing her this incandescently angry. In fact, the last time she hit these heights, they were twenty-five and he’d lost her car keys in the healing field at Glastonbury. They’d been able to laugh about it later, though, alchemise it as an anecdote. Comedy was tragedy plus time, but there’d never be enough distance to make this amusing.

‘Sorry,’ he said quietly. ‘But no. Like we always said. No cheating, ever.’

‘Ever?’ she said, with a knowing intonation.

‘You know what we agreed. I’d tell you.’

Laurie fumed, her chest tight, and tried to breathe through it. The tactlessness and the tastelessness of Dan using things they’d sincerely pledged to each other a lifetime ago. He was currently trashing that memory, and every other memory for that matter, while asking Laurie to treat it as sacred covenant. What an arsehole.

Was he an arsehole? Had he turned into one, somewhere along the line, and she hadn’t noticed? She studied him, as he stared morosely at his hairy knees in his shorts, face like a baleful Moomin.

It didn’t matter. She loved him. They’d long ago passed the point where her love was negotiable; it wasn’t contingent on him not being an arsehole. He was her arsehole.

Laurie had passed that point, anyway. Dan had reached a parallel one where he could abandon her. That’s what it felt like: desolate abandonment. He wouldn’t care about Laurie, from now on? No, no, he did want her. She knew in her guts that he did, which is why this had to be stopped before he did any more damage.

‘But we’ve got to stay at the same company together? How’s that going to fucking work?’

Dan and Laurie managed a few degrees of separation at Salter & Rowson by being in different departments, but once they were exes that would hardly be enough.

‘I can start looking for other positions. I might jack it all in. I’m not sure yet.’

‘Honestly, Dan, it still sounds like you’re freaked out by having a baby and have decided to go full nuke from orbit to fix it,’ Laurie said, in a final stab at returning them to any sort of normality. ‘You don’t want to go travelling, for fuck’s sake. They wouldn’t let you stay head of the department, either. And you hated a week in Santorini, last year.’

As Laurie said it, she wondered if the missing element in that analysis was that he hated it with her.

‘Having children is only one part of it. The reason it’s made me do something about how I feel is because you can’t go back on that decision, you can’t un-have a baby. It made me decide. I don’t want this life, Laurie, I’m sorry. I know it’s a shock after all this time. It shocks me too. That’s why it took me so long to face up to it. But I don’t. Want it.’

‘You don’t want me?’

A heavy pause, where Laurie felt Dan steel himself to say it.

‘Not like this.’

‘Then how?’

Dan shrugged and blinked through tears.

‘The word you’re looking for is no,’ Laurie said.

Tears flash flooded down her face now and he made to get up and she frantically gestured: don’t come near me.

‘Erm … just you know, one minor objection on my part,’ she said, voice thick and distorted by crying. It was ambitious to try to put on a sarcastic tone. ‘How am I going to have kids with anyone now, Dan? I’m thirty-six.’

‘You still can!’ he said, imploringly, nodding. ‘That’s not old, these days.’

‘With who? When? Am I going to meet someone next week? Get things moving on conceiving a few months after that?’

‘C’mon. You’re you. You’re a massive catch, always have been. You won’t be short of offers. You’ll be inundated.’

Laurie finally accepted in that moment, that this was real, they really might be over.

Dan had always had the healthy, normal amount of male jealousy. If anything, more than average: he’d always been sure if one of them would be stolen away by a rival, it was Laurie. Male friends who complimented her in his presence always got a ‘hey now …’ from Dan that was entirely joking but also not. Male hires at her firm always got an early warning that she might not have a wedding ring but she wasn’t single and also the guy was here on premises, so watch yourself, and she assumed this was by Dan or briefed by his representatives. (She’d never had to tell anyone she was ‘spoken for’, anyway, they always mentioned oh you’re Dan Price’s girlfriend. Funny phrase, that. Why was someone speaking for you?)

If the idea of her having kids with someone else got this shrug of a response, this mediocre auto-response, something had flown.

‘Such a massive catch, you’ll pass me up?’

‘We’ve been together all our lives, Laurie, you’re my only serious girlfriend. It’s not like I’m walking away lightly, or that I never cared.’

Laurie was on the back foot. He’d planned for this. He was a politician who had notes; she’d been ambushed.

She still couldn’t believe he wasn’t exaggerating somehow, but there was a dreadful binary: if he could say all this and not mean it utterly sincerely, that would make it even worse.

There was a huge, bewildering gap in all of this for Laurie. An untold mystery in how Dan had gone from unpacking the Ocado delivery, and complaining about the plain digestives they got as substitutions for Jaffa Cakes, going for musty pints of stout in their local and laughing at dogs with overbites in Beech Road Park on a Sunday morning, to this final, total departure, with nothing in between.

It was as if one minute she’d been running for a bus, and the next she’d woken up in a hospital bed, the quilt flat where her legs used to be, with a doctor explaining they were ever so sorry but there was no saving them.

‘Good to know you used to care,’ she said, hearing how plaintive and bitter her voice sounded, in the darkened sitting room. ‘Small mercies? Or is that meant to be a big mercy?’

‘I do care.’

‘Just not enough to stay.’

Dan stared blankly.

‘Say it,’ Laurie said, with force.

‘No.’

It was the logical conclusion of everything he’d said; and yet that hard monosyllable surprised her so much, he might as well have slapped her.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.